Time for Transportation

Well after midnight last Monday evening – or more precisely, Tuesday morning – council chambers were empty of the public except for The Chronicle and a WCC journalism student. The main event (601 S. Forest) was over. What was Eli Cooper, the city’s transportation program manager, still doing there? Earlier in the day, he’d been on hand for the local unveiling of Ann Arbor’s contribution to Rails to Trails Conservancy’s 2010 Campaign for Active Transportation, so starting from that point he’d had at least a 12-hour day.

Ann Street

Was Cooper there for the agenda item addressing the conversion of Ann Street to one-way eastbound between Fifth and Division streets and the addition of some angled on-street parking? No. It was other project staff who appeared at the podium to answer councilmember Marcia Higgins’ question about the timing of the project’s implementation. The change was originally scheduled for the Sunday before the Nov. 4 Tuesday election, but Higgins’ request that it be delayed until after voting took place – to avoid the potential for confusion among voters trying to get to the polls – was accommodated with a rescheduling to Nov. 9. So starting Nov. 9, Ann Street between Fifth and Division will be one-way heading east. Drivers accustomed to turning left from Division onto Ann will need to circle the block instead.

Councilmember Stephen Kunselman asked staff to consider what happens when people circle of the block – down to Catherine, left on Catherine to Fifth, left on Fifth to Ann. Given that the street is one-way, will drivers be able to make a left on red, Kunselman wondered? The provisional answer from staff seemed to be yes.

Councilmember Leigh Greden, acknowledging that he’d missed the council work session where the plan had been laid out in detail, was somewhat taken aback by the seemingly incorrectly angled parking spaces designed on Ann Street. As his council colleagues explained to Greden, the spaces, into which drivers back their cars, are a safer configuration than one where drivers must back out of the spaces. Greden good-naturedly warned that it will take some time for people to get used to that. It was hard not to see a connection between that sentiment and one expressed earlier in the evening by Greden on a completely different topic: “Change is not easy for me as a person. I have my routines … ”

The Ann Street re-configuration is driven in part by the pending construction of the police-courts facility, and the goal of making up part of the loss of some on-site public parking at the Larcom Building.

2010 Campaign for Active Transportation

The event Cooper had attended earlier in the day, unveiling Ann Arbor’s contribution to the Rails to Trails Conservancy’s 2010 Campaign for Active Transportation, reflected work that had begun in April of this year. At that time Cooper had presented to city council the RTT’s invitation to participate as one of 40 communities in a request for $2 billion worth of federal money – $50 million per community. Despite the fact that the primary association that many people have with RTT is the conversion of abandoned railways to bicycle and walking paths, the 2010 Active Transportation campaign is not by any stretch restricted to that kind of project.

Ann Arbor’s task was to articulate in concrete terms how the money could be used locally – its “case statement.” It wasn’t as if Ann Arbor as a community had to start from scratch. Reading through the document produced for RTT’s campaign [.pdf], it’s apparent that it relies heavily on existing policy documents like the Non-motorized Plan. The executive summary of Ann Arbor’s 2010 case statement identifies three key priorities:

- connecting the dots of 38 miles of new on-road bike lanes, 25 miles of new sidewalks, and 128 major pedestrian crossing improvements

- overcoming the barriers formed by a ring of highways without safe crossing options

- and launching the Allen Creek Greenway while completing the regional Border-to-Border Trail

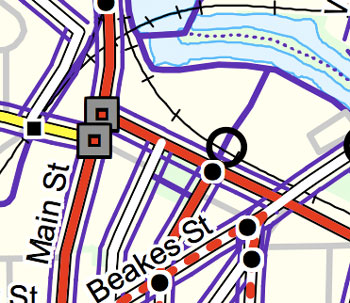

One possible option to allow safe crossings of railroad tracks is to tunnel under the tracks. Supporting documents for the Non-motorized Plan include a city map of possible improvements in the Depot Street area.

That map indicates one place where such an underpass (open black circle) could help connect the city to the Huron River path system.

Talking to The Chronicle during a break in Monday night’s long council meeting, Cooper said that cooperation from the railroad for construction of an underpass is still obviously essential to undertaking that kind of project. The other essential ingredient, said Cooper, is money.

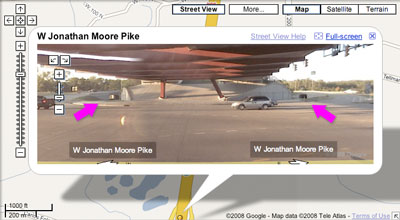

It’s worth noting that construction of railroad or highway entrance ramp underpasses for non-motorized vehicles is not unprecedented, even for communities much smaller than Ann Arbor. For example, in the city of Columbus, Indiana (population 35,000), the People Trail extends from the city out along Highway 46 past the interchange with I-65. The trail includes tunnels under the entrance and exit ramps to the interstate.

Pink arrows indicate underpasses for non-motorized trail under the entrance and exit ramps for I-65 in Columbus, Indiana. This extracted image is linked to the original GoogleMaps StreetView for readers interested in "driving" back and forth.

Circulation of the Transportation Plan Update

What Cooper was at Monday night’s council meeting to witness was the passage of a resolution to distribute the draft of the city’s updated Transportation Plan to surrounding municipalities. Who gets a copy? Per state law, the resolution specified:

… the planning commission or legislative body of each city, village or township located within or contiguous to the municipality; the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners; and local public utility and railroad companies, … other relevant groups and organizations that may be interested in the Ann Arbor Transportation Plan Update.

The transportation plan had been available online for a few weeks and had been introduced at public workshops on Sept. 23. Of the two workshop sessions, The Chronicle attended the later one. There were around a dozen people there, which brought the day’s workshop total attendance to around 50. At the later session, the audience actively engaged Cooper and the consultants.

One audience member wanted to know if the studies that went into development of the plan included the possibility of using a more “grid-like” system for AATA buses, as opposed to the mostly hub-and-spoke system currently deployed. The audience member pointed out that the existing route system made it difficult to move around the periphery of the city – along the Stadium Drive corridor, for example. And after hearing the speaker say “Stadium Drive” for the third time, former mayor of Ann Arbor Ingrid Sheldon gently admonished him, “Stadium Boulevard.” Assurances were given that the AATA’s own re-evaluation of its route system was a key study that was included in the development of the draft plan. That re-evaluation concluded that the current system, which is predominantly hub-and-spoke, best served the needs of the AATA as related to its core mission.

Another audience member wanted to know how to get the city to consider the possibility of getting a traffic signal installed at a particular location: near the entrance to Gallup Park along Geddes. In this case, it entailed showing up to a public workshop hosted by the city’s transportation manager and asking about it. Cooper wrote down the location and said that he’d forward the concern to relevant staff.

One major theme in the draft plan is the strategy of using traffic signals to optimize traffic flow in and around the city. The Chronicle followed up by phone after the workshops with Les Sipowski, senior project manager with the city, to get a breakdown of signals currently deployed throughout the city. Sipowski stressed that traffic signals have varying degrees of intelligence – it’s not a matter of being “smart” or not. Here’s a summary:

- SCOOT (Split Cycle Offset Optimisation Technique). Optimizes in real time based on sensors located seven seconds ahead of the intersection. Currently deployed on three main corridors: (i) Plymouth Road from US-23 into the city, (ii) Washtenaw Avenue between US-23 and S. University, and (iii) Eisenhower between Main and US-23.

- Vehicular detection at intersection coordinated via central computer. Examples include State between Ellsworth and Eisenhower.

- Vehicular detection at intersection with no communication to central computer. Vehicular detection allows for skipping of phases if no vehicle is present. Examples include the Fuller corridor.

- Zero vehicular detection with pre-timed coordination with other signals. Examples include the entire downtown grid, which has coordinated timings that are changed during the course of the day to accommodate morning rush hour, the off-peak periods, and the evening rush. A light’s cycle duration ranges from 70 seconds for off-peak times to 90 seconds for rush hours.

The transportation draft plan, as well as the conversation with Sipowski, reflects a future expansion of SCOOT technology deployment in Ann Arbor. We’ve left the British spelling of “optimisation” in place above to foreshadow one possible challenge when it comes to scooting buses through intersections on a priority basis. Even though SCOOT is a Siemens product, and the AATA uses a Siemens product for its bus tracking system, to implement SCOOT’s transit-ready module would require getting the two Siemens products to talk to each other. That’s not as simple as it sounds, says Sipowski.

The transportation draft plan contains non-software alternatives to giving buses priority at intersections: queue-jumping – or in American English, buses can be allowed to “cut the line.” Given a special lane at an intersection, buses would take advantage of signals that give them a head start over traffic in the other lanes headed the same direction.

We’ve assiduously included the word “draft” in the description of the transportation draft plan to emphasize that it’s a draft. That means it’s subject to modifications, clarifications, additions, etc. as a result of input from surrounding communities’ planning bodies, or regular users of the transportation system in Ann Arbor: drivers, bus riders, cyclists, walkers. Some Chronicle readers will fit into all of those categories. The web page set up to introduce the draft plan contains a multitude of links to background documents as well as the draft plan, both as a complete .pdf document and as more manageable chapter-by-chapter .pdf chunks.

We’d encourage Chronicle readers to read at least some of it and send along your input via the interface provided there. The draft won’t be declared final until sometime in early 2009. Go ahead, download a chapter to your hard drive and have a read through it during a lull in a long city council meeting.