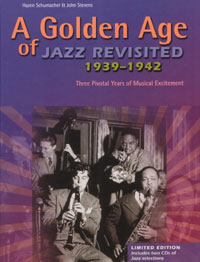

A Golden Age of Jazz Revisited

Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from the introduction to “A Golden Age of Jazz Revisited: 1939-1942″ by Hazen Schumacher and John Stevens, published by NPP Books to be released on Nov. 14. It includes two CDs of music discussed in the book, and will be available online after Nov. 14. Schumacher is an Ann Arbor resident and jazz historian whom most readers will know from his long-time NPR show, “Jazz Revisited.”

Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from the introduction to “A Golden Age of Jazz Revisited: 1939-1942″ by Hazen Schumacher and John Stevens, published by NPP Books to be released on Nov. 14. It includes two CDs of music discussed in the book, and will be available online after Nov. 14. Schumacher is an Ann Arbor resident and jazz historian whom most readers will know from his long-time NPR show, “Jazz Revisited.”

Almost everyone has a connection to a favorite type of music, and many can trace that connection to their years as a teen or a young adult. Music critic Whitney Balliett put it this way in The New Yorker: “The music that teenagers like penetrates their bones.” It’s as if we stop discovering new music at some point in our lives and continue to explore the music we already love.

For me the music that captured my soul was the jazz of the late 1930s and early 1940s. As a teenager in Detroit I grabbed at every chance to hear the popular music of the time at concerts, in movie theaters, and especially on the radio. My changes increased when I went into service and was stationed first near New York City and later near Los Angeles. The little money found in my pockets paid for prowling the jazz haunts of those two great cities.

Years later, after service and college, I discovered that my tastes had changed. Now, instead of the mostly ensemble recordings of the big band era, I was more interested in the small group records of the same period. Though the big band sounds were deep in my “bones,” the recordings of Teddy Wilson & Billy Holiday and the small groups of Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Lionel Hampton soared into my heart and head as well. I marvelled at the exquisite solos and the virtuosity of interplay in the small group sessions. So I looked at the whole period with different eyes (and ears!), reaching the conclusion that something extraordinary had gone on. I certainly enjoyed and appreciated the jazz of the ’50s and on, but the earlier period stayed with me.

A special period for jazz that this book will examine began in the summer of 1939. The Great Depression was pretty well over. Records were selling briskly and jukeboxes hummed. The airwaves throbbed to jazz. The general public knew the names of more jazz musicians than they ever had before or would since. Hundreds of bands criss-crossed the land. Jazz had moved out of the back alleys and into Carnegie Hall. War was approaching – but in the USA it was to a boogie beat. The period ended abruptly three years later when America’s entry into World War II and a musicians’ recording strike coincided.

Popular music in this three-year period was exceptional in quantity, quality, and diversity. William Gottlieb wrote in his book, “The Golden Age of Jazz,” that the late ’30s through the ’40s was “the only time when the most widely-acclaimed music was the best music.”

Sounding a similar note was S. Frederick Starr. In his review of Gunther Schuller’s “The Swing Era,” Staff suggested: “For sheer excitement and creative ferment the years 1930-45 have no equal in the long history of jazz. In that period jazz attained the highest level of enduring art and at the same time gained mass popularity.” Record producer John Hammond praised the musicians who played on the superb Teddy Wilson & Billy Holiday sessions: “It simply was a Golden Age; America was overflowing with a dozen truly superlative performers on every instrument.”

Many of the great jazz performers were active during the three years 1939-42, from the New Orleans veterans to the young musicians who would take jazz into its next phase. In “Since Yesterday,” author Frederick Lewis Allen said that the period “…accompanied the sharpest gain in musical knowledge and musical taste that the American people had ever achieved.”

People all over the world had become enthralled with this vital and distinctively American art form. While the dance bands were drawing crowds, jazz was noticed by scholars both here and in Europe.

The music was in flux. In 1939 many jazz writers insisted that only the New Orleans style, improvised by small groups, was worthy of the name “Jazz.” They decried swing bands as imposters. Three years later, others insisted that bebop was the only jazz, and that big bands were as old-fashioned as Dixieland. Leaving a precise definition of jazz to each reader’s choice, this book will be broadly inclusive in its approach.

Was there truly a “Golden Age” of jazz? Some insist that there was and that it ended in the late ’20s with the Louis Armstrong Hot Five and the Bix Beiderbecke-Frankie Trumbauer records. Others might argue that it didn’t begin until the 1940s with Charlie Parker or the 1950s with Miles Davis.

We think that the period covered in this book was “a” golden age and we have organized it around 55 recordings to illustrate the point. These are not offered as the 55 best records, but rather to show the styles and repertoires of key jazz groups and artists. Most are available in modern formats.

Editor’s note: The following is a sampling of the 55 records discussed in “A Golden Age of Jazz Revisited: 1939-1942″:

- Erskine Hawkins, “Tuxedo Junction”

- Fats Waller, “Squeeze Me”

- Count Basie, “Lester Leaps In”

- Muggsy Spanier, “Dipper Mouth Blues”

- Billie Holiday, “The Man I Love”

- Cab Calloway, “Pickin’ The Cabbage”

- Louis Armstrong/Sidney Bechet, “Coal Cart Blues”

- Artie Shaw, “Star Dust”

- Woody Herman, “Blue Flame”

- Gene Krupa, “Let Me Off Uptown”

- Ella Fitzgerald, “I Got It Bad”

- Stan Kenton, “Adios”

- Lu Watters, “Muskrat Ramble”

- Benny Goodman, “Why Don’t You Do Right”

Jazz is a great part of American history. Artists like Charlie Parker can be considered the Mozarts of America. Jazz continues in modern times and there are still jazz musicians that are pushing the musical boundaries.

I grew up listening to jazz because my father was a jazz musician. When I was younger loved the big band music of the 30′s and 40′s. Now my tastes have changed and I prefer modern jazz with a world music feel.

Jazz has such a wonderful spirit about it. There’s no other type of music quite like jazz, especially from a few decades ago. I just read a post on Peterman’s Eye about Miles Davis and his influence on jazz music…it’s a wonderful read and I thought I’d share.

http://www.petermanseye.com/anthologies/cowboys/374-restless-spirit

Cheers!