Turbulent Origins of Ann Arbor’s First Earth Day

The sixties are known for being one of most turbulent decades in American history. Ironically, however, perhaps the most turbulent year of the sixties was actually the first year of the seventies. Before it was even half over, the Weathermen had blown up a townhouse in Greenwich Village, killing three of their own number (including former Ann Arborite Diana Oughton), the unlucky Apollo 13 moon shot had ended in failure, Nixon had invaded Cambodia, four students had been killed at Kent State while protesting the invasion, and a week later, two more students had been killed at Jackson State in Mississippi. Even the Beatles broke up that fateful spring.

A popular button made by U-M student activists to promote their March 1970 teach-in and its tie-in to Earth Day. (Courtesy of John Russell)

The sudden swelling of tension and conflict seen across the nation in early 1970 was also occurring in Ann Arbor. In February, the University of Michigan chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) organized a series of spirited protests against campus recruiters representing corporations such as General Electric that were supplying material for the war in Vietnam. At one of these “recruiter actions,” thirteen protesters were arrested following a street battle with police.

At the same time, a coalition of African-American student groups calling itself the Black Action Movement (BAM) were demanding that the university take immediate steps to increase black enrollment, and threatening a campus-wide strike if their demands were not met. (Eventually, BAM would call the strike, shut down the university for ten days, and win accession to all their demands.) On top of this were almost daily smaller protests and demonstrations on the war, women’s lib, gay rights, tenant’s rights, and nearly all the other sociopolitical issues of the day.

It was into this maelstrom that a group of U-M natural science students dove when they decided to set about organizing a teach-in on the environment, the latest movement to emerge in a nation awash in movements. The students initially desired to keep the teach-in apolitical, sober, and focused on science. In the highly charged atmosphere of the time, such a goal would prove impossible. Ironically, though, the eventual politicization of the teach-in would prove to be a significant factor in making it the watershed event it would ultimately become.

Dead Lakes and Burning Rivers

The environmental movement had taken root as far back as the nineteenth century, but it wasn’t until the middle of the twentieth that it truly began to flower. Environmental awareness built slowly but steadily throughout the fifties and sixties, and then all at once exploded in 1969 following a series of high-profile environmental disasters – a huge oil spill off the coast of Santa Barbara, Lake Erie being proclaimed “dead,” and Ohio’s Cuyahoga River catching fire (again), among others. Ecologists who had for years been fighting to get their concerns about the environment into the national spotlight suddenly found their voices being heard.

One of the most powerful of those voices was that of U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin. In September 1969 Nelson announced his idea for a nationwide protest against the degradation of the environment. Following the lead of the anti-war movement, he proposed a massive series of teach-ins to take place on college campuses the following spring, intended to make Americans more aware of the deadly seriousness of the multitude of threats then facing the environment. (The majority of which, sad to say, are still with us nearly forty years later.)

Nelson’s announcement reached the ears of a small group of energetic U-M natural science students – soon to adopt the name Environmental Action for Survival, or ENACT – while they were already hard at work on their own teach-in event. It was an idea that was occurring to many people around that same time. Bill Manning, who was one of those original U-M students and is now the managing partner of an organic food-processing company, sees an analogy with a pan of popcorn. “You have kernels that have been heated up,” he explains, “and all of a sudden a whole bunch of them start to go off, almost simultaneously.”

ENACT quickly made contact with Nelson’s group in Washington. “Once we found out about the committee in D.C., we were perfectly happy to start working with them, and share back and forth,” remembers Manning. For its part, the national group recognized the value and importance of what was taking place at Michigan and invited forestry student Doug Scott, co-chairman of ENACT, to sit on their board. Scott, now Policy Director for the Campaign for America’s Wilderness, was one of only two students so engaged. (This was before student activist Denis Hayes was hired to coordinate the national effort.)

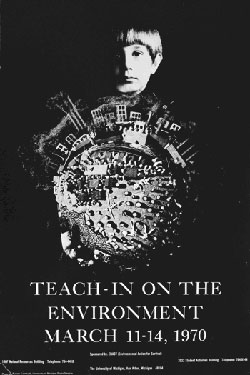

One of the first tasks facing the national organization was to choose a date for the proposed mass teach-ins. They settled on April 22 – “Earth Day,” as it would eventually be named – largely because that date fell optimally between spring break and final exams for most American colleges. (The fact that it is also Lenin’s birthday is apparently a complete coincidence.) But the University of Michigan operated then as now on a trimester system, with April 22 falling right in the middle of finals. As a result, the U-M environmental teach-in was scheduled for mid-March 1970.

The fact that it took place more than a month prior to national Earth Day has led to the misconception that the ENACT teach-in launched Earth Day, or that U-M was host to the first Earth Day celebration. In fact there were environmental events on other campuses as early as December 1969. But that does not in any way diminish the importance of the Ann Arbor event, which was to have a huge influence on the course of what has been called the largest mass demonstration in American history – Earth Day 1970, in which an estimated 20 million people participated.

“The University of Michigan teach-in was not the first or even the second or third – a few small liberal arts colleges had environmental teach-ins in January and February 1970,” says Adam Rome, a professor of history at Penn State who is working on a book about Earth Day. ”But the Michigan event was by far the biggest, best, and most influential of the pre-Earth Day teach-ins. The media gave it tremendous coverage. It was the first sign that Earth Day would be a big deal.”

Make No Small Plans

The members of ENACT knew that Earth Day was going to be a big deal long before their teach-in took place. In the fall of ’69 someone in the group came up with a catchy slogan, based on a John Lennon song that had debuted in July: “Give Earth a Chance.” “We started making buttons using the slogan, with our contact number carefully printed on the rim of the button,” remembers Doug Scott. ”We had a button-making machine at first, but then had to order frequently from a button maker. We had an incredible demand – thousands and thousands of buttons – from beyond Ann Arbor, with orders from all over the place.”

After that things started to snowball, and the event began to develop a will of its own. “When the conditions are right, an idea can spread like wildfire, and that’s pretty much what happened,” says Bill Manning. More and more people became involved. Money began to pour in, from local sources and others farther afield, including such unlikely benefactors as Dow Chemical, which contributed $5,000. ENACT would eventually raise an astonishing $70,000 to support their teach-in (a number made even more astonishing when it is adjusted for inflation and becomes nearly $400,000 today). They raised so much money that they weren’t able to spend it all.

David Allan, then a natural science graduate student and now Acting Dean of the U-M School of Natural Resources and Environment, marvels at the memory of the way events developed. “A lot of what is amazing about the teach-in is that it wasn’t that hard,” he says. “It just kind of happened, in this very organic way. We were able to get venues, we were able to get funding. The media came to us. A lot of things just kind of came together.”

As fall passed into winter, ENACT began to hold “mini-events” on campus and around town. The positive response to these events encouraged them to push the boundaries. “Make no small plans” became their motto. The national Earth Day group actually started getting a little worried, according to Bill Manning. “They were very concerned that we were so far ahead that we might dominate the whole Earth Day activities simply by our event being in March.”

But ENACT had no intention of holding back. The ambitiousness of their plans drew the attention of leading figures in industry, media, science, and government. Across the country, many eyes were turned toward Ann Arbor, watching with great interest to see how the teach-in would come off. Many in industry were undoubtedly hoping for a humiliating failure. But even the anxious ecologists who had their fingers crossed for success weren’t expecting it to turn out the way it did.

The “ENACT Teach-In on the Environment,” as it was officially titled, was a staggering success, attracting more people and attention than anyone could have imagined. An estimated 50,000 attendees were drawn to the more than 125 seminars, speeches, workshops, panels, symposia, debates, forums, rallies, demonstrations, films, field trips, concerts, and colloquia that unfolded over five days at locations on campus and all around town. “There’d never been anything like this,” says John Russell, a teacher at Pioneer High who sat on the ENACT steering committee. “We had sessions where we were shutting the doors and turning people away.”

Events ran from the early morning until well after midnight, on topics such as overpopulation – “Sock It to Motherhood: Make Love, Not Babies” – the future of the Great Lakes, the root causes of the ecological crisis, and the effect of war on the environment. More than sixty major media outlets covered the action, including all three American television networks and a film crew from Japan. It was the biggest such event that had yet been seen in Ann Arbor – and coming as it did at the tail end of the sixties, it would be one of the last.

At the kickoff rally around 14,000 people paid fifty cents to crowd into Crisler Arena and listen to speeches by Senator Gaylord Nelson, Michigan governor William Milliken, radio personality Arthur Godfrey, and ecologist Barry Commoner, and groove to the music of Hair and Gordon Lightfoot. Another 3,000 who couldn’t get in listened on loudspeakers that were hastily set up in the parking lot.

Other events from the teach-in which stand out today include the driving of an all-electric car by Godfrey from Detroit to Ann Arbor at posted speeds on I-94; a panel at Pioneer High attended by 4,000 in which Dow Chemical president Ted Doan was mercilessly heckled but stood his ground, earning a measure of grudging respect from the crowd; the demolition of a broken-down old car on the U-M Diag by a crowd of sledgehammer-wielding students; and provocative speeches by Ralph Nader, environmental lawyer Victor “Sue the Bastards!” Yannacone, and radical ecologist Murray Bookchin, among others.

And then, after five days of almost non-stop activity and little sleep, it was over. Organizers were left feeling both elated and mournful. “A couple of us were clearing out the office when Luther Carter from Science magazine walked in,” remembers Doug Scott. “He remarked, almost in passing, that neither of us would ever again organize anything reaching that scale. For some reason, that really struck home.”

But the ENACT teach-in wasn’t actually quite finished. The events and people from Ann Arbor continued to exert a strong influence on the other Earth Day activities taking place that spring. James Swan, a member of the ENACT steering committee who was also a part-time folksinger and guitarist as well as being the de facto entertainment coordinator for the teach-in, went on to have a hand in twenty-two other teach-ins on campuses around the country in the weeks leading up to April 22. Others who had worked on the Ann Arbor event did the same.

The influence of ENACT reached even farther when the national Earth Day committee started sending out a description of the Ann Arbor event to those inquiring about how to organize their own teach-in. Closer to home, the legacy of that original ENACT team can still be felt today, mainly in the form of the Ann Arbor Ecology Center. Using money left over from the teach-in, group members – many of whom would soon graduate and move away – organized the Ecology Center in order to leave something permanent behind in the community.

Becoming Politicized

One of the most remarkable aspects of the ENACT teach-in was how it managed to include most of the major sociopolitical issues of the day, as well as environmental science, under the wide blanket of ecology. The planners of the teach-in went to great lengths to make the event as inclusive as possible. The war, women’s liberation, racial equality, and social justice were made part of the discussion to show how these issues were interconnected with the environment.

Apparently it was the more radical elements of the campus community who were most responsible for bringing these broader political issues to the teach-in. Stephen Sporn was a member of SDS who was studying environmental psychology when not picketing campus recruiters or attending anti-war demonstrations. He also sat on the ENACT steering committee. “Most of the committee would have felt more comfortable listening to Lawrence Welk than Jefferson Airplane,” says Sporn with a laugh. “I played the role of the ‘token’ radical. It seemed like my job was to push the envelope way past what was acceptable and hope for something else in the compromise.”

The presence of firebrands such as Sporn resulted in planning meetings that could quickly become heated. “The steering committee represented a broad diversity of the campus, politically and academically,” explains James Swan. Young Republicans could find themselves seated next to left-wing radicals fresh from a protest march. “Some of the meetings were pretty passionate,” says Swan. “I remember one that almost became a brawl.”

Sporn, now a naturopathic physician, recalls an argument that developed over whether or not to sponsor a panel on how the war in Vietnam was affecting the environment there. “The steering committee viewed the tie-in to the war as too much, too alienating, and felt that it would upset the public and be too far-reaching for the teach-in,” he says. Ultimately a panel on the war would be organized, and made part of the major series of events scheduled for the last day of the teach-in.

Over the course of the ENACT teach-in, it was the events that were of an edgier, more provocative nature that tended to be best attended and receive the greatest attention from the media, and therefore presumably had the biggest impact. In addition to the car smash, which attracted the most television coverage, another widely-reported event consisted of a march to the Coca-Cola bottler on South Industrial Avenue by a group of students who dumped 10,000 non-returnable bottles and cans on the lawn. (They later picked them up and put them in the trash.)

Also, judging by newspaper reports, it was the more radical speakers, such as Murray Bookchin and Ralph Nader, who made the greatest impression. Their speeches called for dramatic lifestyle changes and even a complete restructuring of society, something that resonates today as the same things are being proposed once again as possibly the only lasting solution to climate change and the other environmental threats we presently face.

Given the tremendous wave of environmental concern then sweeping the country, as well as the vast sum of money they were able to raise and the caliber of the speakers they were able to recruit, the ENACT teach-in was almost certain to be a big draw. But it was the politicization of the event – the radical influence that widened its scope to include many of the crucial issues of the day, and show their interconnectedness – that made the teach-in something that even conservative Business Week could admire, calling it “a remarkable series of debates on America’s values and political systems, all under the umbrella of environment.”

Everybody Get Together Right Now

Of course it wasn’t just the moderates and conservatives whose views were modified by their participation in the teach-in. The radicals learned the art of compromise and also that the environment was as important as the other sociopolitical issues of the time. Today it is a marvel to see the way these normally combative groups came together in a coalition for the common good. In some ways the America of the sixties was less divided than it is now.

Bill Manning sees an important lesson to be learned from Earth Day 1970. “There is nothing to be gained by further fragmenting the world we live in and exacerbating existing adversarial relationships; it seems pretty clear that more antagonism only leads to more conflict, not enduring and effective solutions,” he says. “At the most basic level, if we take care of the process, workable and healthy solutions are far more likely to emerge. And really, isn’t this our experience in all our relationships, from the most intimate to the larger circles we are connected to?”

About the author: Alan Glenn is currently at work a documentary film about Ann Arbor in the sixties. Visit the film’s Web site for more information. While there you can contribute your memories of that time – and read those that others have contributed – in a public forum set up expressly for that purpose.

A fine piece of writing; it brought back a lot of memories and the challenges of the sixties. I’ll never forget when President Richard M. Nixon gave use the EPA and thought that Director Bill Rugglehouse and his young team of 23 would give us a waterdown department. Nixon always regretted his appointment to the EPA until the last of his years when he learned of its many successes!

I still have the “Give Earth A Chance” original button!

It’s great to learn about the history of ENACT! I am a member of the current student group, which is a tight knit group of activists working mostly on education and outreach in the student population and local elementary schools. Hats off to the originals who made all this happen. It’s inspiring!

Excellent article. Thanks for writing it.

Three members of Weatherman were killed in the Greenwich Village townhouse; Diana Oughton, Teddy Gold and Terry Robbins.

I was there at Crisler Arena – and wish I had saved my button! (Sue, you should give it to the Bentley Library.) William Milliken was a great Governor, one whom most of us Democrats voted for. The Michigan Environmental Council gives an award each year named for him. Good environmental policy originates here in AA – Lana Pollack is retiring as the MEC Director and has been replaced by Chris Kolb. It’s important work, and FINALLY people are recognizing that. Great article – this is yet another reason why I love the Chronicle.

Danny V is correct – only three members of Weatherman were killed in the Greenwich Village explosion. My mistake. Thank you for pointing that out.

I attended several of the ENACT teach-ins and remember those lively debates well. Later that year I took some of the buttons to Germany and distributed them to family members and friends. They were somewhat amused and thought that this was yet another American fad. A few years later they became part of the growing environmentalist movement in Germany.