The Day a Beatle Came to Town

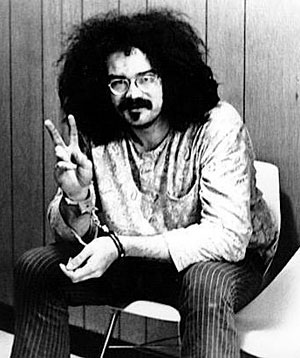

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, playing at the 1971 John Sinclair Freedom Rally at Crisler Arena. (Photo courtesy Leni Sinclair.)

The passage of nearly four decades can dim even the keenest of memories. But to Hiawatha Bailey, the events of that winter afternoon in 1971 are as clear as if they had happened yesterday. Bailey was 23 and working at the communal headquarters of the Rainbow People’s Party in the ramshackle old mansion at 1520 Hill Street in Ann Arbor.

“I was doing office duty,” he recalls, “which entailed sitting at the front desk and answering the phone. Some friends were there, and we were sitting around, tripping on acid, probably, and the phone rings. I pick it up and I hear this voice, ‘Hello, this is Yoko Ono.’”

Bailey, of course, didn’t believe it for a second. “I said something like, ‘Yeah, this is Timothy Leary,’ and hung up. We all got a good laugh out of it.” A few minutes later the phone rang again. This time the voice on the other end said, “Hello, can I speak to David Sinclair, Chief of Staff of the Rainbow People’s Party. This is John Lennon of the Beatles.”

“I wasn’t even that familiar with the Beatles then,” says Bailey, now lead singer for the Cult Heroes, an Ann Arbor-based punk rock band. “I was more into the Stooges and the MC5, more radical rock ’n’ roll. But I knew right away that it really was John Lennon.” He put the call through.

“Dave and John talked for quite some time,” Bailey recalls. “Lennon said, ‘I heard about the benefit that you blokes are putting on, and I wrote a little ditty about John Sinclair and his plight. I’d like to come there and perform it.’”

They Gave Him Ten for Two

John Sinclair – poet, pothead, cultural revolutionary, and Chairman of the Rainbow People’s Party of Ann Arbor, Michigan – was at that time confined to the state prison in Jackson. More than two years earlier he had received a nine-and-a-half to ten-year sentence for the possession of 11.50 grains of marijuana – two joints’ worth – following a trial marked by numerous irregularities.

“The powers-that-be in Michigan had it in for me,” says Sinclair, who now lives in Amsterdam. “They didn’t like what we were doing, establishing an alternative community, defying their authority, smoking grass. First in Detroit, then in Ann Arbor. They fixed on me because I was the most outspoken, and also because somehow I was successful in bringing young people around to my way of thinking.”

Even those who weren’t quite as certain of Sinclair’s blamelessness agreed that ten years in prison for possession of two joints was an unusually severe sentence, and probably politically motivated.

“They wanted to put me away,” Sinclair says, “and so they did.” Following the sentencing, a request for an appeal bond was denied, and the 27-year-old cultural activist went directly to a maximum-security prison.

Sinclair’s sudden departure sent the collective into a state of shock. But his wife Leni and brother David quickly assumed leadership roles and began to direct the effort to free their party’s leader.

In the coming months they worked tirelessly, organizing benefit concerts, demonstrations, and rallies. Wherever possible they enlisted the aid of sympathetic movement celebrities – Allen Ginsberg, Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman (whose misguided attempt to win support for Sinclair at Woodstock during the Who’s set earned him a bump on the head, courtesy Pete Townshend’s guitar), Tom Hayden, and others. But after two years of diligent effort they seemed no closer to getting John out of jail.

At some point in the summer of 1971, Sinclair – who was still helping to lead the party from behind bars – decided that what they needed to do was organize one huge benefit rally for the end of the year. With the help of sympathetic student organizations they were able to secure the use of the University of Michigan’s recently constructed Crisler Arena for Dec. 10. (That’s also international Human Rights Day – although no one seemed to realize it at the time.)

A Total Bomb

Utilizing the contacts that they had built up over the years, Leni, David, and the others assembled a list of about a dozen radical speakers and musical performers who agreed to appear at the rally. Then they approached Peter Andrews, an experienced area music promoter who was working as events director at the university. Andrews was a friend of John Sinclair and had previously organized a few small benefit concerts on his behalf. But he wasn’t interested in producing this show.

“I just looked at it and said, ‘This is a total bomb you have on your hands. You’ll get three thousand people tops, and in the fifteen-thousand-capacity Crisler, it’ll only show how little people care about John Sinclair.’”

Andrews, now semi-retired and living in Ypsilanti Township, recalls that the Sinclairs weren’t willing to take no for an answer. “I went to Toronto with my girlfriend just to get away from them for a few days. When I got back, Leni came to see me and she said, ‘John Lennon and Yoko Ono want to play at the rally!’”

Andrews was skeptical, thinking that this might simply be a ploy to get him involved. “I said, ‘Oh, really. And who’s the headliner, Jesus Christ?’”

Leni Sinclair insisted that it was real, however, and explained that Jerry Rubin had talked the Lennons into doing it. Andrews was still doubtful but agreed to fly to New York and meet with John and Yoko. Even today he still marvels at the surreality of that trip to New York with Leni in December of 1971.

Some Time in New York City

“Nobody met us or anything,” he says. “The only thing we had was a telephone number to call. I remember putting a dime in the phone, and dialing the number. John Lennon answered. He said, ‘Oh yeah, we’ve been waiting for ya, come on over, here’s where we’re at, great!’ I hung up the phone and looked at Leni, and I said, ‘We’re hot, we are happening.’”

Sinclair and Andrews took a cab from Grand Central Station to the Lennons’ two-room apartment in the West Village. “They greeted us, they were very friendly, very, very nice,” says Andrews. “I had Lennon sign a contract for $500 to appear, and he crossed it out and put, ‘To be donated to the John Sinclair Freedom Fund.’”

The visitors from Michigan spent about an hour talking with their newfound allies. At one point, Lennon asked Andrews to come into the bedroom and listen to a song he had written to perform at the concert. “He wasn’t sure if the song was appropriate, and he wanted my opinion. He sang the song – ‘It ain’t fair, John Sinclair’ – with that steel guitar he had. I assured him it was totally appropriate, and the lyrics were cool. He was very grateful.”

Andrews shakes his head in wonder at the memory. “I thought to myself, ‘John Lennon’s asking my opinion! Man, this is somethin’ else.’”

After leaving the apartment they had gone only about a block before Andrews realized that even with a signed contract as evidence, no one was going to believe that John Lennon would be at the show. “So we went back, and I asked John if he had a cassette recorder. I wrote a little script out, and he and Yoko read it into the recorder. Now I knew we had it.”

The Magic of John and Yoko

On Wednesday, Dec. 8, two days before the concert, the Committee to Free John Sinclair held a press conference in Ann Arbor. The tape that Peter Andrews had made was played for representatives of the local and national media.

“Hello, this is John with Yoko here,” began the recorded message. “I just want to say we’re coming along to the John Sinclair bust fund rally to say hello. I won’t be bringing a band or nothing like that because I’m only here as a tourist, but I’ll probably fetch me guitar, and I know we have a song that we wrote for John [Sinclair]. So that’s that.”

Tickets went on sale that same day at $3 each. “It sold out in such short amount of time – two or three hours, statewide – that we actually had guards, uniformed guards, to protect the people that got tickets from the ones that didn’t,” says Peter Andrews. “We distributed tickets statewide so that people would have an opportunity – not a big opportunity, but you had a chance if you ran down there and got in line.”

Andrews recalls that they didn’t spend a penny on advertising. It was enough to simply make the announcement of John and Yoko’s participation and let the media take it from there.

From Mop Top to Working-Class Hero

After the breakup of the Beatles, and before his untimely death by an assassin’s bullet in 1980, John Lennon performed in public on only a handful of occasions. In retrospect it may seem odd that one of these was a benefit for a jailed longhair in the cultural backwater of Michigan. But at the time it made perfect sense.

Ann Arbor was in the forefront of the radical movement of the late ’60s and early ’70s. That same period found the famously outspoken Beatle becoming deeply involved in political activism – denouncing war and injustice, attending demonstrations, concocting peace-themed “happenings” with Yoko, encouraging his fans to “Imagine no possessions,” advising them that “A working-class hero is something to be.”

In the summer of ’71 John and Yoko moved to New York on a more-or-less permanent basis and quickly became close with Yippie activists Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. Rubin was committed to speaking at the John Sinclair Freedom Rally in December, and encouraged John and Yoko to appear, as well.

It wasn’t difficult to get Lennon interested. He’d been toying with the idea of doing a series of all-star concerts combining rock music with radical rhetoric. After long discussions with Rubin, this morphed into an “anti-Nixon tour” that would travel across the U.S. during the summer of ’72 and wind up in San Diego at the Republican National Convention in August.

The rally in Ann Arbor would serve as a trial run.

Not in Kansas Anymore

John and Yoko arrived with little fanfare in Detroit on Friday, Dec. 10, the day of the concert. Peter Andrews picked them up at the airport in a borrowed limousine and drove them to the Campus Inn in Ann Arbor, where a number of the evening’s musical acts were staying. Andrews had booked the Lennons into the presidential suite.

The crowd at the 1971 John Sinclair Freedom Rally in Crisler Arena. (Photo courtesy of David Fenton.)

“I thought it was funny to put them up in the presidential suite,” he says, “because this was basically all anti-Nixon. I remember stopping over there to make sure everything was cool. I couldn’t stay, but boy, I wish could have. They were all jamming up in Lennon’s suite. I thought, ‘Damn, this is too much.’”

The event had grown so big so fast that to many of those involved it felt like a waking dream. “It was madness, all of these people, all the music and the politics,” says Hiawatha Bailey. While working backstage at the rally he felt a sudden need for a few minutes away, and walked over to the nearby football stadium.

“I’m sitting there, in this huge, empty stadium,” Bailey recalls. “All of a sudden this whirling dervish picks up a pile of trash, goes around the stadium, and drops it right next to me.” He smiles and shakes his head. “I’m thinking that I’d better get out of there, before Dorothy and Toto show up!”

But for Bailey the unreality wasn’t quite over. “I go back to the arena, and up comes this limo, and John Lennon, Yoko Ono, David Peel and the Lower East Side and all those scalawags that he hung out with, all start piling out. John says to me, ‘You look like someone I can trust, mate, come with me.’”

Bailey became an impromptu bodyguard, helping to hold back the fans as the Lennons and their entourage entered the arena. “These people were ready to rip me apart to get to John Lennon,” he says. “They had their albums they wanted signed, and they were very vehement about it.”

After escorting the company to their dressing room, Bailey recalls, “John turns to me and says, ‘Watch the door.’ Then he hands me a bag of coke, and says to enjoy myself. So I’m leaning up against the door, holding a bag of John Lennon’s blow, and behind me he’s teaching David Peel and those guys the chords to ‘John Sinclair.’ And I’m just like, ‘Man, this is far out.’”

A Long Day’s Night

Peel would have plenty of time to learn the song – John and Yoko didn’t end up taking the stage until around three in the morning, more than two hours behind schedule. They were preceded by nearly eight hours of speakers and musical performers that included Allen Ginsberg, Jerry Rubin, Bob Seger, Phil Ochs, Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, poet Ed Sanders, Black Panther Party chairman Bobby Seale, Chicago Seven defendant Rennie Davis, radical priest Father James Groppi, and jazz legend Archie Shepp.

The dramatic high point of the evening was a surprise telephone call from the imprisoned John Sinclair that was broadcast live over the arena’s loudspeakers. Voice choking with emotion, Sinclair spoke to his wife and daughter, conveying his belief that they would soon be reunited. “You could almost see the tears flowing down the aisles,” remembers Peter Andrews.

According to many reports, the other non-musical portions of the program did not appear to have a great impact on the audience. The singers, however, seemed to go over somewhat better. According to the Michigan Daily, Bob Seger was “dynamite,” Commander Cody “kept the audience pretty satisfied,” and Phil Ochs was “good and clever.”

But the big musical hit of the evening – possibly even bigger than the Lennons – was a performer that most people didn’t even know would be there.

A few days before the concert, Peter Andrews was working in his office when the phone rang. It was Stevie Wonder.

After his meeting in New York with John and Yoko, Andrews thought nothing could faze him. But now here he was listening to the wunderkind of soul tell him that, even though he wasn’t in favor of marijuana, he was dismayed by what had happened to John Sinclair, and wanted to be part of the show.

“I’m going, ‘Holy shit.’ I didn’t need a draw, so I decided that Stevie Wonder would be a surprise act. I told him over the phone that I didn’t want anybody knowing about this, and not to make any announcements or anything. There were only about three people other than me that even knew about it until he showed up with his equipment.”

Stevie Wonder performing at the 1971 John Sinclair Freedom Rally. (Photo courtesty of Stanley Livingston.)

The Wonder of Stevie

Twenty-two-year-old Jane Hassinger was elated when she learned that Stevie Wonder would be appearing that night. As a member of Drug Help, a local grassroots counseling service for youth with drug and alcohol issues, she was working in one of the arena’s two “drug tents” when Wonder took the stage. “I’d been on the job almost the whole time and didn’t really have an opportunity to watch the show,” she recalls.

“But I said to my co-workers, ‘I’m leaving for Stevie Wonder.’ I went up close to the stage. And he was extraordinary. It was as magical as anything I can think of. There was a roar when he came on.”

“We’d all grown up on Motown,” explains Peter Andrews. “When Stevie came out the crowd went bananas. I just loved it, as the promoter of the show. I still almost tear up when I think of the emotion people had.”

It wasn’t just the crowd that went bananas, either. “When Stevie was about to go on, I thought I should tell the Lennons,” says Andrews. “Well, John just flipped. He goes, ‘Stevie Wonder! I gotta see him!’”

Andrews didn’t think that was a good idea, as the ex-Beatle was certain to be mobbed. But Lennon was insistent. “He said, ‘Peter, don’t you understand? Stevie Wonder is my Beatles!’ He’d never seen Stevie perform. So I agreed. We got like ten security guys, and John Lennon and myself were in the middle of the circle, and we went to the back of the stage to watch.”

Yoko Ono and John Lennon performing at the 1971 John Sinclair Freedom Rally at Crisler Arena. (Photo courtesy of David Fenton.)

Gimme Some Truth

Stevie Wonder wasn’t there simply to dazzle the audience with his music, however. Like all the performers he was also there to make a political statement.

“Before coming here today,” he said at one point, “I had a lot of things on my mind, a lot of things that you don’t have to see to understand. We are in a very troublesome time today in the world. A time in which a man can get 12 years in prison for possession of marijuana, and another who can kill four students at Kent State and come out free.”

“What kind of shit is that?” he asked the crowd, which responded with a roar.

The audience had also cheered earlier in the evening when Phil Ochs delivered the refrain of his song about the White House’s resident paranoiac:

Here’s to the land you’ve torn out the heart of

Richard Nixon, find yourself another country to be part of

But of all the performances that night, it was that of the star attractions which was the most overtly political.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono took the stage at around three in the morning. Backed by an improvised band that included David Peel and Jerry Rubin, they sang about the Attica uprising, about the conflict in Northern Ireland, about women’s liberation, and, finally, about the man of the hour, without whom none of it would have been possible:

It ain’t fair, John Sinclair

In the stir for breathing air

Won’t you care for John Sinclair?

In the stir for breathing air

They gave him ten for two

What else can Judge Colombo do?

Gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta gotta set him free

Then abruptly the Lennons were gone, and the show was over.

Don’t Let Us Down

Monday’s edition of the Detroit News contained a review of the rally that ran under the headline, “Lennon Let His Followers Down.”

Of course, not everyone in the audience was disappointed with Lennon’s performance. But it’s easy to see how many would have been somewhat less than impressed. The ex-Beatle’s set was entirely acoustic, long before going “unplugged” became fashionable. He played only four songs, none of which were familiar to the audience. And he left the stage after about 15 minutes.

“Yeah, I was disappointed by John and Yoko’s ‘street art’ performance,” says Jeff Alder, then an eighteen-year-old aspiring musician. “I mean, the great Beatle jamming with Jerry Rubin playing bongos or congas or something he had no idea how to play, along with David Peel and the freakin’ lousy Lower East Side. But I was still impressed that John came to support our guy.”

Alder, who today works as a studio technician at the University of Michigan, remembers being much more affected by Stevie Wonder’s performance. “Like John L., it was real impressive that he even came to play. Only Stevie actually came to play!”

But Alder admits that these are minor points. The bigger goal was to show support for John Sinclair. “The coolest thing of all was that it worked,” he says. “Regardless of any critiques of the performances and all the yapping, it worked.”

“We got John out!”

Bring Him to His Wife and Kids

Seventy-two hours after the commencement of the rally, John Sinclair was free.

For a brief moment the state penitentiary in Jackson became the backdrop for a scene out of some sort of freaky countercultural version of “It’s a Wonderful Life.” As flashbulbs popped and movie cameras rolled, the burly, long-haired revolutionary enjoyed a tearful reunion with his tiny wife Leni and their young daughter Sunny after almost two-and-a-half years apart.

This was no miracle, however. Rather, it was the result of years of concerted effort on the part of hundreds of people, not just to free John Sinclair but also to reform what many felt were the state’s draconian drug laws.

The day before the rally, the Michigan State Senate passed a bill that drastically reduced penalties for marijuana possession. Three days after the rally, the Michigan Supreme Court granted Sinclair bail pending appeal, after having denied six previous such requests.

The question remains about how much of an effect the event itself had on winning Sinclair’s freedom. The timing is, of course, very suggestive. The justices, however, maintained that their decision was made solely in light of the passage of the new drug bill.

Peter Andrews thinks that even without the spectacle of the rally, Sinclair would have eventually been released. “What it did,” he suggests, “was say, ‘How about right now!’”

However it happened, John Sinclair was out, and all who had struggled so long rejoiced. But the denouement wasn’t wholly Capra-esque. Peter Andrews believes that he lost his job as a result of the rally, which was simply too extreme for university administrators.

Disaster also struck John Lennon, who subsequently found himself under intensive FBI surveillance and threat of deportation. The anti-Nixon tour was canceled, and the former Beatle shied away from political activism for the rest of his life.

But Leni Sinclair, for one, remains grateful for John and Yoko’s efforts on behalf of her ex-husband, and is still tickled to have been mentioned in one of Lennon’s songs.

“Just knowing that we’re part of history is a good feeling,” she says.

John Lennon Sat Here

Walking the peaceful, tree-lined streets of Ann Arbor today, one sees little that evokes the time when John Lennon and Yoko Ono came to town to sing for the freedom of John Sinclair. It is difficult to conjure up the passionate, volatile milieu of that bygone era – the demonstrations, the sit-ins, the marchers with their protest signs, the smell of tear gas in the air.

There are a few reminders of the city’s radical past still to be found here and there: Ozone House, the People’s Food Cooperative, the Ecology Center, the Ann Arbor Film Festival – and the Herb David Guitar Studio on the corner of Liberty and Fourth. There the connection to Lennon’s visit is particularly strong – in the back amid rows of guitars sits a chair that Liverpool’s favorite son once occupied nearly 40 years ago.

“He just roamed into the shop that day,” remembers Herb David. “Nobody knew who he was. He was this little red-headed guy who didn’t look like anything you thought John Lennon looked like.”

A chair that John Lennon sat in 38 years ago, at Herb David Guitar Studio in Ann Arbor. (Photo by the author.)

David recognized him, however. “I said, ‘Hi, John.’ He said, ‘I’m not John.’ So I asked who he was. He said, ‘I’m his cousin.’ I said, ‘OK – hello, cousin.’ Then I let him go, and he just roamed around and we talked.” At some point during his visit Lennon felt like taking a load off, and ended up creating an instant curio for David’s shop.

“It’s fun to have,” he says. “It has a mystique. People get excited about sitting down in the chair. I say, ‘Sit in that chair, you’ll feel different.’”

When asked if he really believes that, David grins mischievously.

“You never know,” he says.

Could it be possible? Could the chair somehow be imbued with the spirit of the John Lennon who came to Ann Arbor 38 years ago?

The John Lennon who asked only that we “Give peace a chance,” and who every holiday season wishes all a “Happy Xmas” and assures us that “War is over, if you want it?”

The John Lennon who stood on the stage in Crisler Arena and said to the assembled thousands, “We came here not only to help John [Sinclair] and to spotlight what’s going on, but also to show and to say to all of you that apathy isn’t it, and that we can do something. OK, so flower power didn’t work. So what? We start again.”

Could the spirit of that John Lennon somehow inhabit the chair?

If so, maybe we all should take a minute to sit in it.

Alan Glenn is working on a documentary film about Ann Arbor in the ’60s. Visit the film’s website for more information.

This:

“I wasn’t even that familiar with the Beatles then,” says Bailey”

sounds totally untrue. Anyone living anywhere within the USA in 1971 was completely familiar with The Beatles, whether they liked them or not. To say he was more familiar with “The Stooges” sounds like absolute nonsense.

I missed the rally, due to a few days stay with the feds, but later became friends with John, Leni, Sunny, and David, while crocheting at Mark’s Coffee Shop. John helped make freedom and thus life possible for me. Thanks always.

Spooner

I was living in Ohio, had friends who had an extra ticket at the last second, but missed their phone call. Such is life.

But a couple of years later spoke with a friend who worked as a maid at the Campus Inn at the time who told me John and Yoko tipped her a hundred dollar bill and were super friendly to the staff.

I was there. I worked that day in Detroit driving a truck for a place called The Video Group, Inc. and left a couple hours early for the early evening start of the concert without eating lunch or dinner. I figured we’d grab a bite after the concert. Well, we were in Crisler Arena for another hours without anything to eat because the concert started around 4 and Lennon and his motley crew didn’t come onstage until around 3 a.m. Archie Shepp’s avant garde sax attack around midnight aggravated a headache I had — maybe all that smoke contributed to it, too. But, like Jeff Alder says, the undisputed star of the evening was Stevie Wonder. He put on an amazing performance singing, playing the organ, playing guitar, playing drums even doing a few funny impressions. Commander Cody put on a great show, too, with a crowd-pleasing version of “Seeds and Stems” and “Beat Me Daddy Eight to the Bar.” I remeber they got John Sinclair on the phone from prison and broadcast it over the sound system. He thanked the crowd for their support and talked to his kids.

I remember the concert as about 1/10th music and 9/10ths speeches, set-up, and “in-between-time,” but my perspective should be suspect; after all, I did once fall asleep during a Springsteen concert.

The Rainbow People did more than take drugs and grow their hair, by the way. College friends and I subscribed to the People’s weekly neighborhood grocery program: two bags of Eastern Market vegetables for a few bucks. Between the group of us, we usually figured out what was what, but we were all stumped by kohlrabi. We thought it was from off-world. I called the Rainbow People number once to check on the vegetable schedule, and was greeting by a sing-song-y “Free John Now!” , in a cadence that seemed more appropriate to “Tip Top Bakery!” I’m not knocking the sloganizing; directly or indirectly, it worked.

I’ll vouch for Hiawatha being more familiar with the Stooges than the Beatles, both personally and musically.

I stupidly got in line many hours before the doors opened, thinking I’d get a good seat. Chrysler has many doors, and the one I was standing at was one of the last to be unlocked. I was nearly crushed to death and didn’t even get a very good seat.

The highlights for me were Stevie Wonder and Commander Cody. I was a huge Beatles fan so John’s performance was a bit of a let down although it was great to get to see him.

I’ve still got my souvenir 45 with the Up’s “Free John Now” on one side and Alan Ginsberg’s “Prayer For John Sinclair” on the other. The parking lot was littered with them after the show.

Reminiscing about those days when the White Panthers maintained their big old house on Hill Street: I once took part in a protest rally with a group of White Panthers, including some of their little children, to try to prevent McDonald’s Corp. from tearing down a historic home on Maynard and establishing a franchise there. The historic house was destroyed, the McDonald’s was built, but it was a pretty little building (Hobbs and Black were the architects, I think) although it did not last long at that location–it caused lots of controversy at the time.

this was a fun article to read!

miss the ann arbor & all the great organizations that were;

read poetry with donald hall, john, ed sanders and a lot of other poets at hill aud. shortly after john’s release

so many tragedies, highs and hardships later – remember LB’s limo green bentley of sinclair/lennon fame, too -

There is a 16mm or 8mm homestyle film of this concert somewhere in Ann Arbor. Yoko Ono will not allow its release. Shame on her! Maybe after she is gone, we will get to see it. Funny thing about that chair at Herb David.The first time I saw it, I was told by a clerk that the chair is not the ORIGINAL chair that Lennon sat in.The owner has it at his home supposedly. The second time I wanted to see it with my English friends. The clerk shooed us away and could not be bothered. The other two stories I heard about Lennon and his Ann Arbor visit….he went to the basement of the Blind Pig. (now the 8 Ball)Supposedly he met with some of Ann Arbor’s radical element.Also, stevie wonder was interviewed about this gig, and he commented about the FBI have a large presence at this show.

Stevie Wonder, aged 21, came on at 2:30 AM and said, “This is to any undercover agents in the crowd” and played “Somebody’s Watching You.” Later a FOIA investigation revealed FBI agents were taking down every word. Lennon came out, announced, “The Pope smokes dope” and performed his composition “The Ballad of John Sinclair” and three other original songs with Yoko. Two days later, an appellate court freed Sinclair on bail.

Afterwards, Phil Ochs was wiretapped and followed, and the INS initiated proceedings to deport Lennon because of old pot bust in England. The protracted fight soured him from performing for political causes [but he was planning to do so when he was shot dead in 1980].

Source: Stand and Be Counted by David Crosby and David Bender

http://www.veryimportantpotheads.com/site/lennon.htm

Hey, just want to shout out to Hiawatha that there’s no doubt in my mind that your memory is amazing. Thanks to you I remembered long forgotten episodes from the late ’60s when we hooked up in A2 in 2002. Thanks man, and peace, love & light to you in 2010.

Alan what a wonderful piece of work. The thing that I most enjoy is how it has set-up a framework for others to express as they recall!

Onward through the fog!

All power to the People,

Hiawatha and The Cult Heroes

Mark Hodesh, who now owns the Downtown Home and Garden Store on South Ashley St., owned the nearby Fleetwood Diner at that time.

He reports: “I was working building banquet seats for the Fleetwood that night. After he got out of prison John Sinclair was an occasional customer, his brother David was a regular.”

I used to deliver mail to 1520 Hill St. arriving at the door to put mal in the box was always a hoot. You never knew what you would find or see. I talked to David and Leni many times. They were always friendly and usually funny. While I didn’t subscribe to their lifestyle at that timke Ann arbor had many lifestyles. The 60 & 70s were wild and funny times.