In the Archives: Runway to the Future

Editor’s note: At a recent meeting of the Ann Arbor city council, an item in the city’s capital improvements plan to shift and extend the runway at Ann Arbor’s municipal airport generated much discussion. This installment of “In the Archives” takes a look at Ypsilanti’s airport, which has faded from the landscape.

The delicate blue Waco 10 biplane roared 10 feet over the grass, past the crowd in the stands. Approaching trees at the airfield’s far end, its nose rose and it climbed, becoming smaller and smaller in view.

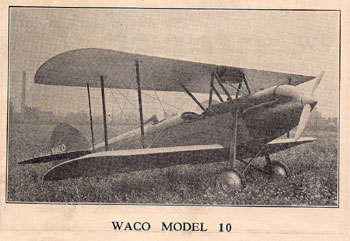

An photograph of a Waco 10 from the airshow program. Five aviators at the 1927 Ypsilanti air show competed in the cutting-edge biplane. (Photos courtesy of the Ypsi Archives.)

The gargling buzz of its 90-horsepower engine grew fainter, until the craft sounded like a distant housefly. Watchers from Detroit, Ypsilanti, and Ann Arbor under the 4 o’clock June sun shaded their eyes with their hands.

The buzz stopped: 1,500 feet in the air, the plane was without power.

The biplane arced to the left, trying to loop back towards the field. The crowd watched intently. The biplane curved again, losing altitude. A box of popcorn fell from the hand of a little boy watching, his mouth open. The plane’s wings wobbled. Airplane and crowd were quiet. On a nearby farm, a dog barked.

The plane dropped. Nearing the field, it slowed, its toylike wheels just a yard over the ground. The plane nearly stalled – and then landed as gently as a butterfly. It rolled to a stop. Its nose nearly touched a black and white checkered pylon. The crowd began clapping and cheering as two men ran to the plane and stretched a yellow measuring tape between the plane’s silver nose and the pylon. One yelled a number. The crowd grew louder, some people standing to cheer and whistle.

The pilot grinned and thrust both fists up. He’d won the “dead-stick” engine-off gliding and landing contest at the 1927 Ypsilanti Airport air show.

Aviators from around the country were there. J. P. Wood had flown his Waco 9 from Big Stone Gap, Virginia to the three-day show. D. Young from San Diego was there with his Ryan M-2. Roy Nass, a 23-year-old Ypsilanti aviator, competed in his Waco 9 against the other 29 flyers, none from Ann Arbor. Half of the aviators flew elegant, almost dainty Waco 9 or Waco 10 biplanes made in Troy, Ohio. Aside from some steel tubing, the planes’ wings and fuselage were made entirely of wood, covered in fabric.

A 1927 air show at the Ypsilanti Airport – near the present-day I-94 and US-23 interchange – drew thousands of spectators.

Like the Wright Brothers’ forerunner 24 years earlier, almost all of the planes at the show were biplanes. Exceptions included Young’s Ryan M-2 and famous Chicago aviator Wilford Yackey’s silver “Yackey Monoplane.” The long wings of the monoplanes required sturdy and heavy reinforcement.

Biplanes offered an equal or greater wing lift area, and their double wings were trussed to each other and to the fuselage in a manner that strengthened the craft and compensated for the relatively fragile materials available to 1920s airplane builders.

Four months after the Ypsilanti air show, Wilford Yackey died while flying. As he performed daring maneuvers near Chicago, one of his monoplane’s wings snapped off.

Hosting famous aviators at the show was not the only point of pride for the Ypsilanti airport, an area that at one time spanned 160 acres, with a northwest corner that’s now crossed by the I-94/US-23 interchange. Two years after the 1927 show, the airport was chosen as the region’s designated airmail stop. The airmail service pilots refused to land at Ann Arbor’s small airport “because of its condition which is unsatisfactory for both landing and taking off,” noted the July 13, 1929 Ypsilanti Daily Press. A courier drove the airmail from the Ypsilanti airport to Ann Arbor.

Ypsilanti was proud of this honor. An airport committee “agreed to obtain additional letters to complete the name ‘Ypsilanti’ on the hangar roof, which now appears in the abbreviated form of ‘Ypsi’,” reported the July 14, 1929 Ypsilanti Daily Press. A bigger beacon light was proposed.

A few days later, the Press reported, “Four planes bearing delegates to a special banquet of real estate men held this noon at the Michigan Union in Ann Arbor . . . were originally scheduled to land at Ann Arbor’s port, but due to conditions there which were made less favorable by a light rain this morn the group chose the local field instead and were driven to Ann Arbor in automobiles.”

This newspaper clipping from the 1947 Ypsilanti Daily Press shows the TWA Constellation, a 51-passenger aircraft.

In 1947, TWA chose Ypsilanti as a stop on its international route. “Nearly 15,000 persons are expected to gather at the Airport here tonight,” reported the June 18, 1947 Ypsilanti Daily Press, “to wish godspeed to 40 passengers scheduled to make the inaugural trans-oceanic flight from Ypsilanti aboard a Trans World Airline four motored Constellation.” An accompanying photo of the Constellation called the 51-passenger craft a “huge aerial argosy.”

When passenger service switched to Detroit Metro Airport in the mid-1960s, the Ypsilanti Airport fell into disuse. By the 1980s it was no more than a peaceful weedy field lined by trees with a crumbling wooden barn-like structure. The airport’s days of glory were gone.

But years earlier, before the excitement of serving as an international stop, the airport was also a source of wonder and distraction to children in the nearby Roberts school. In late winter or spring of 1928, about half a year after the air show, one schoolchild wrote a composition about the airport.

The Ypsilanti Airport is across the fields from our school. It is about a half mile away. When there is a warm day, the man will start some of the planes going, and they fly around over the school.

Sometimes they fly up high, and loop the loop in the air. Then they fly still higher. . . sometimes they made so much noise that it seems as if they were coming down on top of our school. It is hard for us to keep from looking out of the window . . .

Sometimes Ford’s big plane lights [lands] there, but it doesn’t stay too long. Thousands of people were there last summer to the big air meet. We hope they have another meet this year.

The paper suggests that the writer was in the crowd at the air show. The child’s parents likely lived through and remembered the stunning event of the Wright brothers flight. Sitting with parents in the stands, being treated to popcorn, and watching with wonder the beautiful crafts based on the Wright discoveries must have felt like a big party.

Or perhaps even the child saw that these delicate, elegant biplanes were time machines, flying straight into the future, and that everyone in the crowd was a passenger.

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

Last week’s Mystery Artifact generated some shrewd guesses. Cosmonican and Pete correctly guessed that the object in question was a strike-plate for matches. The object has a small sandpaper area on the bottom part. The matches likely were stored in a wall-mounted tin “match safe” nearby, both near a stove in the kitchen.

This week’s Mystery Artifact also has something to do with heat, but its function is far more obscure. Take your best guess and good luck!

“In the Archives” is a biweekly series written for The Ann Arbor Chronicle by Laura Bien. Her work can also be found in the Ypsilanti Citizen, the Ypsilanti Courier, and YpsiNews.com as well as the Ann Arbor Observer. She is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives,” to be released Feb. 25. Bien also writes the historical blog “Dusty Diary” and may be contacted at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

An antique, cast iron glue pot w/ brush. Most likely used by woodworkers to put on hide glue in the last millennium. Had to be heated over a fire in order to soften the glue before it could be applied.

Interesting guess, Mr. Works. As a side note, the inner chamber containing the sticklike object is removable.

is it a fire starter? I have something from my grandmother that looks similar. it has a white ball on the end on the stick that is soaked in black stuff. you light it and then light the wood.

Patty, the Museum has just such a fire-starter; it’s a ball on a stick just as you said, stored in a copper tankard. You guess was quite a good one, and close to the answer! :)

Thanks for an interesting article on early days of aviation and airports in the Ann Arbor/Ypsilanti area. Numerous small airports with sod runways dotted the fields surrounding the Ypsilanti/Ann Arbor area during the first half of the 1900s. For clarification, the TWA Lockheed Constellation operated from the Willow Run Airport (which was associated with Ypsilanti in those days), rather than the Ypsilanti City Airport about which the preceding portion of the article is concerned. Willow Run seems more associated with Belleville in 2010, and is still an operating airport with control tower, charter airlines, corporate flight departments, an airplane museum, aircraft salvage and maintenance, FAA, and training operations based there.

It should also be noted that the Wright Brothers’ December, 1903 flights were little noticed for years, even if they were “stunning” to the few onlookers who saw them. Initial publicity of their four flights was sparse and completely erroneous, and for lack of credible evidence, generally met with skepticism. Their first official public airplane demonstration was in 1905 in Ohio, and they flew no more until 1908 when they were awarded two contracts for airplanes. By that time other inventors, both in the United States and in Europe, were flying their own successful designs derived independently of the Wrights’ discoveries.

Finally it is interesting to note that the sand dunes of southern Lake Michigan was the area of many hundreds of human-carrying glider flights in the late 1800s that long preceded the Wright Brothers’ interest in flying.