In the Archives: Paper Pennies of Ypsi’s Past

Editor’s note: As a feasibility study on local currency gets underway in Ann Arbor, local history columnist Laura Bien takes a look at how local currencies were used in the past. Bien’s new book on local history, “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives (MI): Tripe-Mongers, Parker’s Hair Balsam, The Underwear Club & More (American Chronicles)” can be ordered through Amazon.

Local currencies are nothing new to either Ypsilanti or Ann Arbor. In addition to 19th-century municipal banks, both cities created local currencies about 80 years ago. They weren’t created to boost local spending or civic pride. Ypsilanti created her local currency, called scrip, in the fall of 1931 because the city had no other money to pay municipal employees.

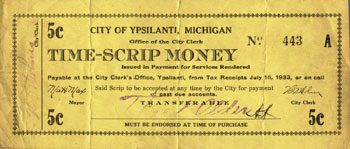

Ypsilanti "Time Scrip Money" was used to pay for municipal work. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

The currency included paper pennies.

“It was really just an IOU,” recalled Paul Ungrodt, in an April 15, 1975 Ypsilanti Press article, one of a Great Depression retrospective series. “[T]here was no money; hardly anyone could afford to pay taxes, so we made do with the scrip.” In the summer of 1929, Ungrodt was proud to have secured the prestigious job of Ypsilanti Chamber of Commerce secretary. A few months later, the stock market crashed.

Ypsilanti’s slide into the Depression wasn’t immediate, but two years after the crash, conditions were grim. Little federal help was available, aside from a few shipments of federal flour and Red Cross cloth. Ypsi Boy Scouts led door-to-door clothing drives. The used clothes were taken to the city welfare office at Michigan Avenue and River Street, “renovated,” and given to the poor.

Church and social groups held canning parties and put up thousands of quarts of food, some for distribution to the poor. One September 1932 Ypsilanti Daily Press article reported that Lincoln schoolgirls in the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades canned peaches, tomatoes, and pepper relish for winter use in their own cafeteria. The girls also put up 65 quarts of concentrated grape juice, made from grapes grown by boys in the school’s “agriculture department.”

In 1931, one city council member proposed that municipal employees in the “streets and parks departments should be put on a four day shift after Oct. 1,” reported a Sept. 22 Daily Press article, “and unemployed men put to work under them in shifts to keep the work done and provide labor for those whom the city must help. These unemployed will be paid in scrip which can be used for specified groceries in any city store.”

To get the streets and parks jobs, the unemployed had to apply for an identification card. Aside from standard questions about age and address, the applicant had to provide the name and address of their previous employer, whether they were in debt on their furniture, car, or anything else, and whether they had received any other aid in the past.

The city received 400 applications. Roughly three-quarters were married men, about half were over 40, and about half were white. Fewer than half owned a home, but rented an apartment, lived in a boarding house, or rented a single room. Almost a third of applicants were the sole supporters of their family, and almost a quarter had more than two dependents. Two women applied.

The number indicated a want that was more pressing than some believed to be the case. “It should be understood,” Paul Ungrodt was quoted in an Oct. 30, 1931 Daily Press article, “that many of these unemployed who have registered, although the total is apparently great, are not hard pressed. Many have relatives and the condition of many others is not serious because they have had work until recently. Furthermore, there are numerous instances where more than one in a family registered.”

As a representative of the city’s economic health, Ungrodt may have felt a need to downplay the problem. Years later in the 1975 Press retrospective article, he characterized the times more negatively. “If your business failed either you were lucky enough to find someone else to work for or you simply did nothing,” he [said]. “But there weren’t jobs for most people. It wasn’t a pretty picture by any means.”

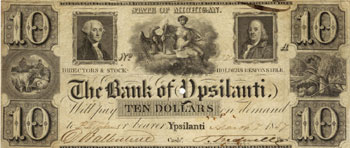

This 1837 currency from the Bank of Ypsilanti features cows, a sheep, and a beehive. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

In preparation for the work program, city officials decided “the city will profit more and the poor as much by a program of work which will be of permanent benefit rather than the creation of odd jobs of no lasting value,” according to an Oct. 10, 1931 Daily Press article. City officials planned a 390-foot sewer as the first project, to be followed by work whose cost in scrip and materials could be covered by bonds issued by the city. City clerk Harvey Holmes designed the scrip, and it was printed in town.

The article concluded, “‘[A]ll who expect dole from the city will be required to give work in return,’ Mayor Matthew Max has insisted.”

Later that month, “[t]he first issue of scrip money by the city of Ypsilanti was made,” said the Oct. 21, 1931 Daily Press, “when City Clerk Harvey Holmes paid seven men a total of $89.25 [$1,250 today, or an average of $180 each].

“Scrip will be accepted only for the articles printed on the back of the money,” continued the article, “and each piece must be signed by the man presenting it. If he cannot write, the merchant accepting the scrip signs for him, and his thumb print is made on the scrip. There will be no change made in either cash or scrip. Persons using it must purchase the full amount they present.

“Scrip is issued in denominations of 1 cent, 5 cents, 10 cents, 25 cents, or $1.”

The list of items scrip could buy was restricted, the article said, to “coal, coke [fuel], bread, navy beans, bacon, baking powder, corn meal, corn starch, canned soup, canned peas, canned tomatoes, canned hominy, canned corn, coffee, crackers, flour, lard, matches, milk, macaroni, oleo, oatmeal, onions, potatoes, pepper, prunes, pancake flour, rice, soap, sugar, salt, [baking] soda, salt pork, tea, and yeast.”

Fresh meat and fish, butter, eggs, cheese, and fresh fruits and vegetables were not allowed.

A year and a half later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed the Federal Emergency Relief Act which granted money to the poor. FERA was followed by other New Deal programs that addressed unemployment. Ypsilanti scrip was phased out.

Today, the surviving examples are only a reminder of the onetime local currency, earned with a pick and shovel, that put food on Ypsilanti tables.

Thanks to Gerry Pety and Derek Spinei for help with images. Images courtesy of Ypsilanti Archives.

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

The previous Mystery Artifact was guessed correctly by Larry Works: a glue pot. He added, “Most likely used by woodworkers to put on hide glue in the last millennium. Had to be heated over a fire in order to soften the glue before it could be applied.” That may be – the Ypsilanti Historical Museum information for this artifact indicates that its inner chamber could be removed to add hot coals into the outer chamber.

This week’s Mystery Artifact, about two feet wide, bristles with a square of pointed metal teeth. Take your best guess and good luck!

“In the Archives” is a biweekly series written for The Ann Arbor Chronicle by Laura Bien. Her work can also be found in the Ypsilanti Citizen, the Ypsilanti Courier, and YpsiNews.com as well as the Ann Arbor Observer. She is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Bien also writes the historical blog “Dusty Diary” and may be contacted at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

Any idea why you couldn’t buy fruit/veggies? Is it because they presumed you had grown them yourself and put them up? Did people have chickens and thus not need eggs? Interesting how the things you could purchase were restricted like that….

This was a very useful and insightful article, and topical since we are exploring a local currency. I hope that those studying the local currency idea will consider it. In my opinion, the only point to a local currency would be to monetize labor or product that would not otherwise have a monetary value. In other words, it is a means of regularizing barter.

In regard to comment #1, I would speculate that the fresh vegetables, eggs, etc., still had a potential monetary value in real US currency. The items listed were of the commodity and survival rations types.

The mystery artifact appears to be a wool separator for weaving on a loom perhaps or spinning wheel.

TeacherPatti: The only theory I could come up with about the restricted foods was that these items were much cheaper, so (I imagine) the city officials who created the currency felt that the scrip wouldn’t be going to “luxuries” instead of basic food for the family.

I have seen a Depression-era grocery receipt that shows that butter, fruit, and eggs were expensive. Here are some prices from that receipt:

1 unit coffee 55 cents

12 oranges 50 c

1 lb salt 10 c

1 bread 12 c

12 eggs 53 c

1 butter 50 c

2 lb cheese 30 c

1 cabbage 6 c

1 pound ham 80 c

3 lemons 17 c

Cabbage was dirt cheap so you wonder why that didn’t make the approved list.

You can see the list over on my blog (click on it for a larger image): [Link]

Ms. Armentrout: I’m glad you liked the article.

Please forgive my ignorance, but I’ve never understood the claim that local currencies monetize labor or products that do not otherwise have a monetary value. I am likely missing something here, but it seems that either labor and product have a monetary value that I’m willing to pay for, or they don’t.

For example, let’s say I need some tree branches trimmed. I could hire an arborist, whose services have a stated monetary value (let’s say their website says they work for $50 an hour) or I could hire my neighbor with a chainsaw and tree-trimming experience, whose tree-trimming services don’t have an “official” value. Yet those services would be of value to me, and I’d be as willing to pay my neighbor as I would an arborist.

If local currencies, like Detroit Cheers, are pegged to the dollar, there’s no reason I’d pay them for things of no monetary value, versus spending dollars for the same things. Every type or labor or product, whether professional services/things in a store or informal services/homemade honey has a monetary value that can be measured in regular money; I don’t grasp why a local currency would “unlock” the value of these things when I’d be perfectly happy to pay regular U.S. dollars for them.

I likely am overlooking something in this argument, however, and would be grateful to learn what that is. Thank you!

Dave: Oddly enough, that was my first guess upon seeing this item, but I was informed that that was not the case. :)

TeacherPatti: Oops, sorry, not to threadjack this comment thread but I didn’t answer all of your question, sorry.

Regarding chickens: the Depression receipt referenced above has several purchases of “scratch feed” which I presume is for chickens. However, the receipt was for a fairly prominent Cleary College administrator who likely owned a home (and yard). Many folks as you know lived in boarding houses/apartments or were roomers/boarders &c. with, it seems, no such opportunity to put up a coop in a backyard (or grow vegetables).

Perhaps I misstated my point. I meant, not that honest labor doesn’t have a monetary value in absolute terms, but that there may be no buyer for it with standard currency. To use your example, what if you had no money to pay either an arborist or your neighbor, but you were willing to do laundry and mending. But your neighbor didn’t need any laundry done. However, he needed some carpentry from someone who did need laundry and mending. By creating a system to monetize your labor that would otherwise have no easily exchangeable value, you would all three benefit. That’s what I meant by regularizing barter.

I’m not at all an economist, but it seems to me that value is created by a willing and able buyer. If no buyer (with cash) exists, no monetary value exists. On a very local level, one can create value by exchanging goods and services, but it is difficult to “price” them. How many cabbages must I grow to get my house painted?

Dear Ms. A.: Not to be argumentative, but it seems to me the system you describe is the one we have now. Everyone has different skills that are not directly exchangeable for the items we need but which are compensated for with money with which we buy the things we need. There’s no reason I couldn’t get paid for my laundry and mending with the money we use now, and then go buy the stuff I need. Barter is in this way already regularized.

If you can sell each cabbage for 50 cents at the Farmer’s Market and it costs $500 to get your house painted, you have to grow 1,000 cabbages, plus some extra to cover transportation and booth rental costs &c (and ignoring the costs of raising the cabbages).

Of course, if you find a housepainter who also runs a sauerkraut factory, you’re in like Flynn. :)

Ms. B, I have only taken a casual interest in this and don’t care to debate it further. The barter system used in other communities assumes that US currency is in short supply. If everyone has plenty of money, let us indeed pay one another with it.

The mystery artifact looks like something known as a flower frog — the spikes hold flowers so they’ll stand up — but it’s a bit weird to have that on a plank of wood, so I may be way off.

Ms. L., I had the exact same reaction (in addition to wool-carding device) when I saw it. I knew that such spiky items are used in flower arranging and ikebana. I was informed that I was wrong. :)

I will haphazard a couple of guesses if that’s allowed. A boot scraper, or a giant meat tenderizer. If it’s a meat tenderizer, I suppose it’s safer than the modern method using a bucket of water and 1/4 stick of dynamite.

(Enigmatically) Interesting guesses, Cosmonican.

And, sure enough, you’re right about the dynamite-in-meat for tenderizing: [Link]

Add that to the ammonia treatment given rendered ground beef: [Link]

Nummy num num.

I’ll venture another guess on the mystery item. Could it be a leather tanning, scraping tool? Maybe a wood graining tool?

The mystery artifact is a hetchel – not sure of the spelling. It is used in preparing flax for spinning. After the flax is retted (soaked in a local pond) it is bundled into small sheaves and slammed down on the nails of the hetchel repeatedly. This breaks the stalks and separates the linen fibers from the rest of the plant. After some further cleaning and currying it is then spun into linen thread for later weaving and sewing. If my memory serves, the finer cleaning and currying was done with thistles which were grown specifically for this purpose. Thistles are now a common weed but were first brought to this country for their use in spinning and weaving. I learned this stuff during a visit to a colonial farm demonstration in Cooperstown, NY around 1965.

Dave: Well, those points are *very* sharp; it’s a pretty fearsome artifact, really; I imagine it might just rip up any sort of hide, really (and even damage wood).

Al: If I recall right, the teasel was also used for currying, though Wikipedia says they were for use with wool. You can see their bristly heads all throughout Gallup Park. [Link]

Teasel. That is what I should have written when I wrote ‘thistle.’ Yes, they used teasels to curry the tangled linen threads before spinning. The display I saw had four teasels fastened to a board with a leather strap so they could be held in one hand while drawing them through the bundle of linen threads.

I neglected to mention that we have been using scrip in the Dexter-Miller community for over two years to pay for and encourage the exchange of simple neighborly services like rides, minor repairs, mending, tool borrowing etc. For more info see our website at DEXMIL.com

Laura Bien: “A year and a half later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed the Federal Emergency Relief Act which granted money to the poor. FERA was followed by other New Deal programs that addressed unemployment. Ypsilanti scrip was phased out.”

Jct: Roosevelt granted not enough money to address unemployment after 1932! There were 8 more years of misery without their local currency lifeboat and an extra 7 million people died! PS: These days your local currencies are good all around the world if you link to the Time Standard of Money (EG: Ithaca Hours, LETS Timebanks). In 1999, I paid for 39/40 nights in Europe with a timebank IOU for a night back in Canada worth 5 Hours. So get your timebank lifeboat online as fast as you can and this time, there’s no shutting them down.

Vivienne Armentrout: “not that honest labor doesn’t have a monetary value in absolute terms, but that there may be no buyer for it with standard currency. To use your example, what if you had no money to pay either an arborist or your neighbor, but you were willing to do laundry and mending. But your neighbor didn’t need any laundry done. However, he needed some carpentry from someone who did need laundry and mending. By creating a system to monetize your labor that would otherwise have no easily exchangeable value, you would all three benefit. That’s what I meant by regularizing barter.”

Jct: That’s what the time-based LETS Local Employment-Trading System currency software was designed to do. With the United Nations International & Local Employment-Trading System on the agenda, In 1999, I paid for 39/40 nights in Europe with a timebank IOU for a night back in Canada worth 5 Hours and you can too.

I’m not at all an economist, but it seems to me that value is created by a willing and able buyer. If no buyer (with cash) exists, no monetary value exists. On a very local level, one can create value by exchanging goods and services, but it is difficult to “price” them. How many cabbages must I grow to get my house painted?

Mr. F.: Oh, that is interesting, to learn that teasels were used for flax as well; neato.

Yep, I’ve read over the Dex-Mil page and my favorite part is the very sensible sharing of tools.

I have often wondered why, on my own street of 30 tiny houses with 30 tiny yards, there are 29 gas mowers (we have a manual push mower, so there) and a slew of gigantic snowblowers. Seems very silly to me.

King: “Roosevelt granted not enough money to address unemployment after 1932! There were 8 more years of misery without their local currency lifeboat and an extra 7 million people died!”

Hmm, not sure who “their” is, or the citation that Roosevelt granted “not enough money after 1932″; FERA along pumped over 3 billion dollars–1930s dollars–into states for welfare and work programs, and that’s not even considering all the other “alphabet soup programs,” as Henry Ford sneeringly called Roosevelt’s programs.

I’ve run into discussions of the weaver’s teasel before and found this neat website showing how it could be employed: [Link]

Ms. Armentrout: Wow, that is really interesting! You can really see how this simple tool was the predecessor or modern carding combs.

I was also fascinated to read the comment about the woman who recalled “teasing” hair into big puffs–I never realized that that expression came (as it seems to) from weaving. Very neat!

Whoopsie, misspoke, there; the teasel-tool would not be a “predecessor” of the carding comb since the c.c. would be used to straighten out fibers prior to spinning and the teasel-tool was, it says, used to “raise the nap” on fabric and make it fluffier.