Environmental Indicators: Phosphorus

Editor’s Note: This is the third in a series written by Ann Arbor city staff on the environmental indicators used by the city of Ann Arbor in its State of Our Environment Report.

The State of Our Environment Report is developed by the city’s environmental commission and designed as a citizen’s reference tool on environmental issues and as an atlas of the management strategies underway that are intended to conserve and protect our environment. The newest version of the report is organized around 10 environmental goals developed by the environmental commission and adopted by the city council in 2007.

Phosphorus takes its place in the periodic table of elements with atomic number 15. Too much P is not good for the Huron River.

This installment focuses on phosphorus levels in our creeks and river. Adrienne Marino is a recent graduate of the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources and Environment and is an Environmental Programs Assistant with the city of Ann Arbor. Matthew Naud is the Environmental Coordinator at the city of Ann Arbor and can be reached at mnaud@a2gov.org. Elizabeth Riggs with the Huron River Watershed Council and Molly Wade with the city of Ann Arbor provided additional input on the regulatory issues.

All installments of the series are available here: Environmental Indicator Series.

April showers will surely give way to May flowers and the start of lawn care season in southeast Michigan. As you tend to your lawn this spring and summer, you should know that your choices regarding lawn maintenance – especially fertilizer application – have large and measurable effects on the health of the Huron River and on the natural and human communities who depend on it.

How do we know this? The city of Ann Arbor’s ordinance regulating phosphorus-based lawn fertilizers took effect at the beginning of 2007. And sampling of Huron River phosphorus levels by University of Michigan scientists shows significant decreases in total phosphorus levels in 2008 and 2009. Huron River Watershed Council sampling of the creeksheds support these findings.

Why Measure Phosphorus?

Applications of lawn fertilizer by residents are an example of non-point sources of phosphorus [chemical symbol P]. That’s different from a single-point source of phosphorus like the city’s waste-water treatment plant. This month’s installment on environmental indicators discusses Total Phosphorus Reductions in the Huron River and chronicles a community-wide effort among residents, non-profits, local governments, and businesses to limit non-point sources of phosphorus to the Huron River.

The city of Ann Arbor is interested in monitoring phosphorus on the Huron River for two basic reasons. First, it’s because the city understands the possible negative environmental impact of excess phosphorus in the river. Second, the amount of phosphorus in the Huron has drawn the attention of the federal government.

So collecting phosphorus data provides information needed to assess progress toward federally mandated phosphorus reduction requirements. Communities in the Middle Huron watershed – which encompasses the land that drains into Ford and Belleville lakes – are under a federal TMDL requirement for phosphorus.

What’s a TMDL?

A TMDL, or Total Maximum Daily Load, is established by the state and quantifies the amount of a pollutant a water body can accept, or assimilate, without violating water quality standards. [We pronounce TMDL like you would "timdle," if that word existed.] This load is calculated based on point source loading, plus non-point source loading, plus a margin of safety.

The TMDL for Ford and Belleville lakes specifies the amount of phosphorus the lakes can assimilate and still meet protected uses – e.g., not stimulate algal blooms, which are rapid population increases of algae in an aquatic system. TMDLs are required for water bodies that are not attaining standards established by the federal Clean Water Act (CWA). The Michigan CWA program is administered by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment [formerly Michigan Department of Environmental Quality].

One algal bloom on Ford Lake in 1991 was so severe that a hazardous materials team was called in to investigate what residents thought was a “green paint spill.” More details on why phosphorus is a problem can be found at the end of this article.

Phosphorus is not inherently a pollutant – it’s an essential nutrient for plant growth. But in excess, it wreaks havoc on aquatic ecosystems, often contributing to nuisance plant growth and algal blooms.

Excess phosphorus enters the Huron River from both point and non-point sources. The main point source under our control is the Ann Arbor wastewater treatment plant. The plant accounts for 43% of Ann Arbor’s cumulative phosphorus input into the Huron River. Point sources have been regulated under the Clean Water Act since the 1970s. The Ann Arbor wastewater plant currently removes most (over 95%) of the phosphorus from wastewater before discharging it into the river. We are doing a very good job controlling the phosphorus in our wastewater.

When phosphorus was first identified as a problem in the Huron River system, the city of Ann Arbor, the Huron River Watershed Council, and other Middle Huron communities relied heavily on public education campaigns and environmental monitoring to inspire voluntary actions that would reduce non-point source phosphorus loading.

In 2007, Ann Arbor developed and passed its ordinance limiting the use of lawn fertilizers containing phosphorus. That came after a decade of investment in public education and research with limited measurable progress toward water quality goals, and a federal mandate (TMDL) to reduce phosphorus levels by 50%.

How Do You Measure a Change in Phosphorus Levels?

Very carefully. Sure, there are sampling and testing protocols to measure phosphorus levels – total phosphorus, soluble reactive phosphorus and dissolved phosphorus. But natural systems are messy and there is a lot of noise in the data. You need lots of good data to measure small changes in the system.

Gathering lots of good data is typically very expensive, and it is rare for it to be affordable by local governments, watershed councils, and even state environmental agencies. Many communities in Michigan and throughout the United States have passed laws regulating phosphorus fertilizers that are similar to Ann Arbor’s. What makes Ann Arbor’s story unique is that it is the only place in the country with good “before” and “after” data. That data show measurable and significant decreases in total phosphorus levels, following implementation of a city-wide ordinance that prohibits the application of phosphorus lawn fertilizers.

Ann Arbor’s data story is better because Dr. John Lehman at UM has a long-term study of nutrients in the Huron River, beginning in 2003, looking at a variety of nutrient levels at key points upstream of Ann Arbor, through Ann Arbor and continuing downstream to Ford and Belleville lakes. The U.S. EPA has supported this effort. This is the part of the story that we like best. Here’s what was going on in 2007:

- EPA had been funding basic research that was not originally intended to evaluate a phosphorus ordinance;

- With this funding, a university professor and students were working on nutrient monitoring in the river and more importantly, they reached out to the watershed community annually to share their research results;

- A separate creekshed modeling effort predicted a significant change (20%) in phosphorus loadings if a ban on phosphorus is implemented; and

- The city enacted a phosphorus ordinance after two years of background work with community partners, knowing that it would have an effect but not sure how much.

Then, quite simply, the parties involved talked to each other.

When we discussed evaluating the effectiveness of our ordinance with Dr. Lehman, he and graduate students proposed a sampling frequency that would measure a statistically significant change of approximately 20%, based on certain assumptions. The city has supported a graduate student to sample at three sites – one upstream control and two in-city experimental sites – for the past two years and again this summer.

What Do the Phosphorus Data Show?

Phosphorus levels in Ann Arbor’s section of the Huron River have gone down over the past two summers when compared to previous years’ data and upstream controls.

This is really good news. It’s a big deal.

When it dropped the first year, we were “cautiously optimistic” that the phosphorus fertilizer ordinance was responsible for a measurable and statistically significant drop in phosphorus levels in the Huron River. After two years of significant drops, we are more optimistic. But we know we do not have a perfect experiment.

A combination of other factors also can influence phosphorus levels – including changes in behavior resulting from continued public education, increased focus on green infrastructure such as stream buffers and rain gardens, and decreased development in the watershed. It is not clear that any of these, individually or combined, would have an effect at the magnitude we are seeing. Regardless, the data do show real decreases in phosphorus levels, an indication that we are moving in the right direction toward meeting our clean water goals.

A Closer Look at the Phosphorus Data

With Dr. Lehman’s pre- and post-ordinance data, it is possible to compare total phosphorus concentrations for 2008 and 2009 sampling periods to a 2003-2005 reference period.

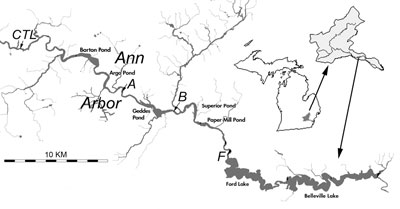

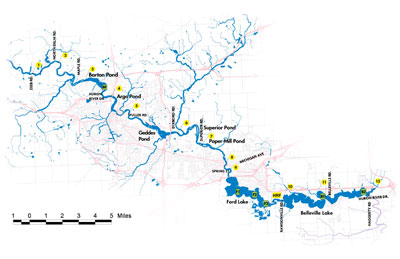

Figure 2. Sample locations – map reproduced here from Reduced River Phosphorus Following Implementation of a Lawn Fertilizer, Lehman, et al. 2009. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Sample sites for this study include:

- A control site (see CTL north of Barton Pond in Figure 2 above) located upstream of Ann Arbor. This site receives drainage from outside the area impacted by the phosphorus fertilizer ordinance.

- Sample site A, located on the Huron River upstream of Geddes Pond. This site drains 11 square miles of Ann Arbor.

- Sample site B, located on the Huron River downstream of Geddes Pond. This site drains 36 square miles of Ann Arbor. Because it drains a larger part of the city, site B may be more responsive to the fertilizer ordinance.

- Sample site F, located downstream of Ann Arbor, upstream of Ford Lake.

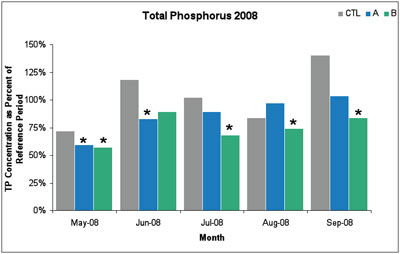

In the first year of sampling (2008), there were six statistically significant decreases in total phosphorus levels between May and September. Compared to the 2003-2005 reference period, the 2008 reductions ranged from 18-43%, with an average reduction of 28%.

Figure 3. In 2008, six out of ten monthly average phosphorus reductions were statistically significant. An asterisk * indicates statistically significant total phosphorus reduction. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

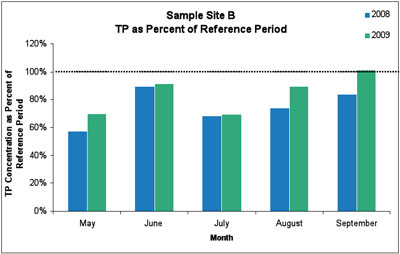

The 2009 data showed similarly significant reductions in total phosphorus, with an average reduction of 17%. In both years, the total phosphorus reductions were only observed at sample sites A and B, but not at the upstream control site. Further, non-target variables sampled at the same time as phosphorus (e.g., nitrate, dissolved organic matter, silica, specific conductance, and pH) did not change over the sampling period.

Figure 4. Total phosphorus levels were below the average measurement from the 2003-2005 reference period (100% line). The average reduction in TP at site B was 17%. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

At this point in the story, we have two years of good data showing statistically significant drops in phosphorus levels. These data suggest that, over the two-year time period, something was happening in Ann Arbor to cause a decrease in Huron River phosphorus levels that was not occurring upstream and not affecting other nutrients.

What Else Do We Know to Support or Refute Conclusions?

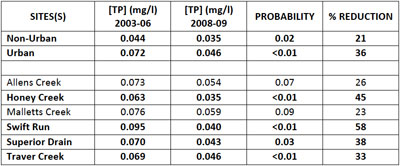

The Huron River Watershed Council, under its Middle Huron Nutrient Monitoring Program, collects data on phosphorus and other variables from tributary streams within and outside Ann Arbor. They also have a growing data set of samples. The results from their data show that after the ordinance went into effect, total phosphorus concentrations (2008-2009 data) for the urban creeksheds were 36% lower on average when compared to pre-ordinance levels. Again, the phosphorus fertilizer ordinance is one explanation for the significant phosphorus reductions in urban creeksheds.

Table 1. HRWC Middle Huron Nutrient Monitoring Program (Ric Lawson). Bold findings are statistically significant. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Verdict on Phosphorus

So we know that phosphorus levels are still higher than we want them to be and the indicator has been set as yellow.

The upward arrow for the phosphorus indicator reflects an improving trend – that phosphorus levels are going down.

We also know, based on good science and statistics, that phosphorus levels have dropped over the past two summers in Ann Arbor and there is creekshed monitoring data that support the river findings.

So we have set the indicator trend as improving, indicated by the upward arrow.

More on Phosphorus and Ann Arbor’s Ordinance

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient found in all living things, as well as in soils and water. Phosphorus promotes healthy root development in plants.

In Michigan freshwater systems – including the Huron River – phosphorus is the limiting nutrient. In other words, the amount of phosphorus in the system controls the growth of plants and algae. Under natural conditions, phosphorus concentrations in freshwater systems are very low, and plants are efficient at getting the nutrients they need.

When excess phosphorus runs off from lawns into lakes and streams, it quickly accelerates the growth of algae and aquatic plants. One could understand, then, how unnecessary applications of phosphorus on land and subsequent runoff into lakes and rivers can lead to significant surface water quality problems.

Just one pound of phosphorus can stimulate the growth of 500 pounds of algae!

As those algae die and decompose, the decay process consumes dissolved oxygen, reducing the available oxygen supply for fish and other aquatic organisms.

Too much phosphorus contributes to the growth of nuisance aquatic vegetation and algae, not just in Ford and Belleville lakes downstream, but in Ann Arbor’s Huron River impoundments (Barton, Argo, and Geddes ponds). Nuisance plant growth reduces the quality of the habitat for aquatic organisms, and it impacts recreational activities like swimming, boating, canoeing, kayaking, rowing, and angling.

Why Did We Focus on Lawn Fertilizer?

Non-point sources of phosphorus in stormwater include soil and fertilizer run-off. Allen, Malletts, Millers, Swift Run, and Traver creeksheds all contribute high phosphorus loads to the Huron River in Ann Arbor. Reducing the application and subsequent runoff of phosphorus by implementing a formal policy regarding lawn fertilizers provided the city the opportunity to meet water quality goals at a relatively low cost.

Moreover, it turns out additional phosphorus is not even needed for healthy turf in most of southeast Michigan. In general, turf fertilizers are developed for national distribution, and they all contain the three macronutrients required for plant growth: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Data from Michigan State University (MSU) Extension shows southeast Michigan soils have adequate phosphorus levels, and, in most cases, do not need supplements to support healthy lawns. Plants cannot absorb the excess phosphorus, and it runs off into our waterways.

Another compelling reason to focus on phosphorus fertilizer was the result of a modeling effort that showed a significant reduction in phosphorus loading to the Huron River was possible if there were full city-wide compliance with a fertilizer ordinance. This modeling, completed as part of the Malletts Creek Restoration Study, showed 100% compliance with the phosphorus ordinance in Malletts Creekshed alone would reduce phosphorus loading by 560 pounds per year. Extrapolating to include all Ann Arbor creeksheds, the expected reduction in total phosphorus was 22%. Two years of post-ordinance data show the expected reductions are on target with observations – total phosphorus levels were 28% lower on average in 2008 and 17% lower in 2009.

What Does Ann Arbor’s Ordinance Require?

Ann Arbor’s ordinance applies only to manufactured lawn fertilizers containing phosphorus. In general, it prohibits the application of phosphorus fertilizers. There are exceptions to the rules if you are establishing new turf or if a soil test from the past three years demonstrates a need for supplemental phosphorus.

For lawn fertilizers, the phosphorus-free varieties list “0” as the middle number on the packaging. Phosphorus free lawn fertilizers are readily available from Ann Arbor retailers. Remember to choose “the hero with the zero.”

Phosphorus and the Rest of the River

Ann Arbor is not the only Huron River watershed community with regulations regarding phosphorus lawn fertilizer. Commerce Township, Hamburg Township, the city of Orchard Lake Village, Charter Township of Pittsfield, and Charter Township of Ypsilanti all have similar ordinances. Several other communities and counties throughout the state have passed or are considering phosphorus fertilizer bans.

With more communities pursuing phosphorus regulations, fertilizer companies and suppliers do worry that it will be difficult to comply with a patchwork of phosphorus fertilizer regulations. Many are responsive to a uniform statewide policy. A statewide ban on phosphorus lawn fertilizer, like the one currently being considered in Lansing by Michigan lawmakers, would provide clarity on guidelines among manufacturers and consumers, and it would eliminate the problem of having to keep track of a range of rules.

Michigan House Bill 5368, introduced by state Rep. Terry Brown (D-Pigeon), would prohibit property owners from using lawn fertilizers containing phosphorus unless a soil test indicates the existing phosphorus level is too low, or the property owner is establishing new turf. The bill is currently pending in the Great Lakes and Environment Committee. If passed and signed into law, Michigan would join Minnesota, Maine, Florida, and Wisconsin as states that have passed phosphorus lawn fertilizer regulations in the past five years.

Paths to Contribution

Cleaner water starts in your yard.

We’re all part of the Huron River watershed, and how we take care of the land impacts our local streams, the river and our neighbors downstream.

Keep lawn care pollutants out of the river by following these tips:

- Take proper care of your lawn to reduce or eliminate the need for fertilizer. Maintain the lawn at a minimum height of three inches and, when you mow, cut no more than one-third the height of the grass. Taller grass has a deeper, healthier root system, is more tolerant of drought, and resists weed infestation. When you mow, mulch the clipping back into the lawn to add nitrogen and organic matter to the soil.

- Choose phosphorus-free fertilizer. Most area lawns already have adequate phosphorus supplies.

- Have the soil tested before applying it, if you think your lawn needs phosphorus,. Contact your county MSU Extension office to find out how to submit a soil sample. On Saturdays throughout April, you can bring a soil sample to one of several Washtenaw County retailers for testing by the MSU Extension. See this flier for more information, including instructions for collecting a soil sample.

- Keep fertilizer on the lawn, and off hard pavement. Immediately sweep up any spills, especially on sidewalks and driveways, with a broom. Never wash spilled fertilizers off pavement with a hose.

- Never apply fertilizer right before a storm or to frozen ground.

- Avoid applying fertilizer within 25 feet of any wetland, stream, waterway, or stormwater basin.

- Prevent soil erosion from your property – phosphorus binds to sediment, and finds its way to waterways when soils run off during wet weather events.

In addition to practicing river-safe lawn care, make an effort to purchase other phosphorus-free products. Did you know that some dishwasher detergents can contain up to 8% phosphorus? Choosing low or no-phosphorus products reduces the amount of nutrient that must be removed at the wastewater treatment plant, which is Ann Arbor’s largest source of phosphorus to the Huron River. Beginning July 1, 2010, manufacturers will no longer be allowed to sell detergents with more than 0.5% phosphorus in Michigan.

Voice your support for statewide phosphorus lawn fertilizer legislation. Contact your state representative to speak in support of statewide restrictions on phosphorus lawn fertilizer use. This law will help improve water quality in streams and rivers statewide, and in the Great Lakes.

Finally, celebrate the Huron River this spring, summer and fall.

Get to know the amazing resource flowing through the heart of our city by taking a canoe trip, visiting riverfront parks, or volunteering to keep natural areas in good condition.

An article on Van Buren County efforts to limit phosphorus :[link]

This is very interesting, according to your article

“Further, non-target variables sampled at the same time as phosphorus (e.g., nitrate, dissolved organic matter, silica, specific conductance, and pH) did not change over the sampling period.”

Most lawn fertilizers have all free nutrients, usually 9 to 10 times more nitrogen than phosphate. Nitrogen is a lot more mobile than phosphate, so if you have not seen any reductions in nitrogen I would ask if the city has increased the frequency of their street sweeping program.

Did the city buy a new more effective street sweeper?

Given that more than 75% of phosphate losses from turf occur when the ground is frozen [peer reviewed research from Wisconsin (Kussow) and Minnesota (Horgan)] you need to sample year round before you start to make conclusions.

Jim,

Thanks for the comments. Let me know if you have direct links to the research you cite above. We recognize that there are many reasons why phosphorus levels could drop. Fertilizer, fewer building projects (less soil runoff), and you have added street sweeping. I will check on how that has changed or not. I believe we have added one additional city sweep in the spring for stormwater. I am not sure if that would provide the magnitiude of change Dr. Lehman is seeing or would provide the change for the whole may, june, july season. Thanks for taking the time to think about this with us.

Matt and Jim,

Interesting discussion. The fertilizer ordinance did not address overall fertilizer use — only P content. Fertilizer sales and use would be expected to be about the same, thus, one would not expect a change in N levels following the implementation of the ordinance.

I cannot speak for Dr. Lehman’s sampling, but our tributary sampling program runs during the May-September growing season, because those are the months that the TMDL regulation is in effect. Effects from overnutrification are not seen outside of the growing season. That is the target, so that is when we sample, along with the fact that winter sampling is logistically much more difficult.

It is very difficult to EVER draw direct conclusions from environmental results. However, it is reasonable to put all the available information together and then look for the most likely explanation if there is a consistent result. Additional sampling would always improve our understanding, but as of now one cannot rule OUT a positive effect from the ordinance and the preponderance of evidence suggests a positive correlation.