In the Archives: Golden Age of Oysters

Editor’s note: For this installment of Laura Bien’s bi-weekly local history column she takes the Gulf oil spill as an opportunity to drill down into the local area history of oysters.

The nation-wide restaurant chain Red Lobster is pulling oysters from its menu. So are other seafood restaurants around the country.

The nation’s oldest continually-operating oyster-shucking company, New Orleans’s P&J’s, has shut down. Nearby is French Quarter neighbor Antoine’s, New Orleans’ oldest restaurant that allegedly invented the sumptuous dish Oysters Rockefeller. The restaurant has kept the recipe secret to this day.

Less occult is that restaurants around the country who rely on Gulf oysters are in trouble. According to NOAA, the Gulf supplied around 67% percent of the nation’s oysters.

Closer to home and over 150 years ago, oysters came from a different coast. Packed in barrels and whisked from New York and Chesapeake Bay to Washtenaw on trains, oysters were a popular area food.

Some were unloaded from the Ypsi train depot in 1845 and hauled to George Collins’ Oyster Saloon. Collins’ ad in the May 26, 1846 Ypsilanti Sentinel says “his stock of Tea, Coffee, Sugar, Molasses, Confectionaries, &c. &c. far surpasses any thing in the market. He has also fitted up a convenient Oyster Saloon adjoining his store, where he is prepared to serve the lovers of this luxury to the utmost of their wishes.”

Oyster saloons in general ranged from opulent dining palaces to less elaborate eateries and even dives associated with gambling and prostitution. The menu usually included raw, stewed, broiled, and fried oysters.

Ypsilanti’s James Forsyth expanded this model with his 1859 “Oyster and Billiard Saloon” on Huron between Pearl Street and Michigan Avenue. Local papers ran ads for Detroit oyster packer D. D. Mallory and the “Oyster Ocean” restaurant at Woodward and Jefferson avenues, which presumably served the bivalve. In the ’60s, Depot Town grocer W. K. Horner stocked mackerel, salmon, lobster, and live oysters.

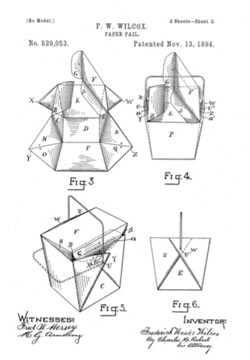

Customers who wished to cook them at home were given their purchase in a paper oyster-pail. Numerous inventors filed patents for such paper containers for oysters in the late 19th and early 20th century. When oyster stocks declined and takeout food became more popular after World War II, it’s said the unused stocks of paper oyster pails were adopted for takeout. Today’s standard Chinese takeout comes in an oyster-pail.

Outside of home, oyster suppers were for years a popular local form of social supper. Often held in a church and combined with entertainment, the suppers were frequently fundraisers. Diners could usually choose from a variety of oyster dishes but oyster stew was a mainstay.

“The Wesleyan Guild of the Methodist church gives a novel entertainment in the church parlors next Monday evening,” wrote the January 18, 1889 Ann Arbor Argus. “It is to be a “Conversazione” where, to the music of the Chequamegons [local orchestra] five minute conversations will be enjoyed, on topics assigned by the program. An oyster supper is promised. Admission fee of 10 cents [$2.40 today].”

Everyone liked oysters, it seemed. However, one well-known Michigan man stood up against the mollusk.

Former EMU and UM student J. Harvey Kellogg took a dim view of oysters. In a talk he gave to the state horticultural society in 1907, Kellogg brought the gavel down.

He described a banquet he’d attended. “The first thing on the bill of fare was oysters. I did not want any. Why?

“In the first place, the oyster is a scavenger; his business is to lick off the slime at the bottom of the sea; you catch the oyster down there; he has got his broad lips open and licking off the slime; he likes that slime because it is full of germs . . .

He continued, “Lemon juice will kill not only oyster germs, but typhoid fever germs. Oyster germs are typhoid fever germs. That is why people get typhoid fever sometimes by eating raw oysters. If you are fond of typhoid fever germs, oysters on the half shell will be a good way to get them. The oyster lives largely on typhoid fever germs. He likes them. You can almost always find typhoid fever germs in oyster stomachs.”

At the time, Kellogg was hosting the state horticultural society at his Battle Creek San for the meeting, which included a dinner. The menu at the San banquet – or rather, the San meal – included roasted Protose, a meat substitute made of beans blended with peanut butter. Other delectables included “Nut and Rice Croquettes,” and “Wafers,” all washed down with “NoKo.”

A 1909 advertisement in the Ypsilanti Daily Press shows a gentleman who apparently did not ascribe to the austere Kellogg diet. The ad touts the “Sealshipt” method of packing oyster meats in a sanitary can. The company even offered a book about its method, should the reader be intrigued. The ad lists three Ypsilanti grocers who carried the trademark white china crock from which the oyster meats were dipped into a take-home container. The ad also shows the item of cutlery designed just for oysters: the dainty bident oyster fork.

The age of oysters, however, was slowly coming to a close.

Over the course of the 1900s, oyster stocks dwindled and the food became more expensive. In November of 1931, Ypsilanti’s elegant Huron Hotel included them in one of its weekly Sunday dinners. However, the oyster was no longer the main dish as at past oyster suppers. The entrees included grilled Mackinac trout, fried veal porterhouse, baked chicken, and filet mignon. Oysters appeared merely as an “oyster cocktail” appetizer.

Today, live oysters can be purchased from the aquaria within Hua Xing Asian Market on Washtenaw. About a dozen lay in the tank when I visited recently. They seemed like just a tiny remnant of the hundreds of thousands of oysters over the decades that once delighted diners all over Washtenaw County.

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

In the last column cmadler demonstrated an almost preternatural ability to guess the weirdest of artifacts, though there were a lot of quite imaginative and reasonable ideas.

It was a revolution in stilts, invented by Ypsilantian Thomas J. Sheears [sic?] in 1873. I have not been able to find this gentleman in the old city directories. However, in the 1860 census there is a “Thomas Shears,” listed as a white Kentucky-born 25-year-old cabinetmaker living with some other unrelated possible apprentices in the home of Ypsilanti cabinetmaker and undertaker David Coon and his wife Eliza.

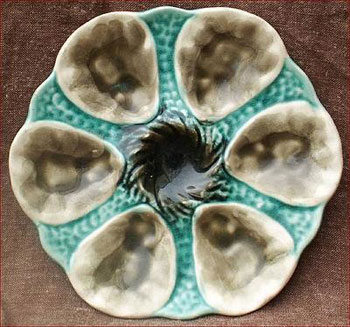

This week’s Mystery Artifact is an elegant item that’s sadly vanished from most modern china cabinets – come to think of it, there aren’t many of those around anymore, either. See if you can figure it out and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales of the Ypsilanti Archives.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

About oysters from that other [New York] coast. My sister Nancy Ralph is founder and director of the New York Food Museum. The first exhibition, 10 years ago, was about “How New York Ate 100 Years Ago”. They ate oysters–tons and mountains of them. You can see the online version of the exhibition at [link]

NY preservationists are striving to keep afloat the last remaining oyster barge from the oyster heydays. Pollution mitigation is reviving hopes of renewed oyster beds just off Manhattan island where the barges used to dock and sell directly to the restaurants.

Thanks for the local slant on the heydays of oysters–100 years ago. [The mystery object is no mystery in southern Maryland or tidewater areas. It is a plate for serving oysters, of course. A family member has her own small collection of these usually flamboyant items, like the lovely one pictured.]

Alice: That is just fascinating. I wish I could see that exhibit. Is there anything more interesting than the history of foodways? There is so much information and culture inherent in the kinds of things a given group of people ate. I see other interesting past exhibits on the page you kindly linked to. I’d love to see this museum.

In AA of course there is the nationally-recognized food history collection at the Clements Library, a real treasure. Lots of simply wonderful artifacts in there.

I read somewhere in my research that in line with your “mountains” of oysters comment that there were hundreds of oyster saloons and simple roadside stands in NYC in the late 19th century. They were everywhere.

And I must leave an obligatory Mencken quote here:

“The largest genuine Maryland oyster—the veritable bivalve of the Chesapeake…is as large as your open hand. A magnificent, matchless reptile! Hard to swallow? Dangerous? Perhaps to the novice, the dastard. But to the veteran of the raw bar, the man of trained and lusty esophagus, a thing of prolonged and kaleidoscopic flavors, a slow sipping saturnalia, a delirium of joy!” –H. L. Mencken, 1913

Interesting article as always. Thank you. I’m going to guess that an oyster dish for the mystery artifact would be too easy. A deviled egg dish, perhaps?

Let’s not forget that wonderful dish: Angels On Horseback, which was a raw oyster on top of thin sliced bread, wrapped with bacon and skewered with a toothpick then grilled until the bacon was cooked. I was at a wedding reception a few years back with a retro menu and those were the most popular item.

I remember reading though (don’t remember where) that the Midwestern popularity of the oysters from the opening of the Erie Canal until refrigeration became common, had a lot to do with them being competitive in price with beef and other meats, and especially because they were fresh — live when you cooked them, not sold a week after slaughter and shipped in ice and sawdust like beef, which often was tough and full of maggots by the time it was served.

Barbara: Or would “too easy” be a stealth move to make it seem…too easy? :D

Cosmonican: That appetizer sounds scrumptious. Bacon + oyster = delectableness.

That is really a fascinating detail about the beef. It makes perfect sense. Oysters, if not shipped shucked, were of course live and fresh when they arrived in AA and Ypsi stores.

I would be less than charmed if my nice beef roast had…some extra protein (stomach churns).

It is so obviously a plate for serving oysters, and it appeared a bit out of place in my feed reader, that my first thought was, “Hmmm, she left out the mystery item picture!”

And since last fortnight you challenged me to silly guesses, I will suggest that it is:

- A palette for painting, particularly seascapes.

- A special dish used by restaurants to serve a sampler platter of six soups, with a spot for oyster crackers in the middle.

- A somewhat melted attempt at putting suction cups on a frisbee.

- A dish used by a jeweler to display loose pearls.

- An early mock-up for the Lord of the Rings movies of the eye of Sauron.

- A dish used to taste-test different grades of Michigan beet sugar.

On a more serious note, was there any food or activity that people enjoy that Kellogg didn’t find time to argue against? If he had lived longer, he probably would have suggested that watching television leads to blindness and that computer use causes the brain to liquefy and evaporate through the ears.

Heck, he probably didn’t even like Michigan beet sugar.

cmadler: I love your silly guesses. It could actually be used as a little paint palette; that would work, seems to me. To tell you the truth, as of last week I did not know what this item was. I probably would have guessed that it was a Seder plate.

It is definitely not a Seder plate. :)

Kellogg was quite a character. In truth, I have a lot of admiration for him. Some of his ideas were a tad wacky, but I get the strong impression that he was acting at all times according to his beliefs–whether they were strictly medically correct by modern standards or not. Likely he made money hand over fist due to the San, but I never got the impression that that was his object. My impression is that he viewed himself as a man with a responsibility to bring wisdom and plain common sense to the people for their betterment.

I think he acted with integrity according to what he viewed his mission to be…I have to respect that. I’m not arguing with you, mind, just blabbing.

And to mention just one data point; he did live to be 91, after all. All those years of Protose may have paid off. :)

I also should say that the movie “The Road to Wellville” does him very short shrift and annoys me. They took the cheap cartoonish route with that movie, and the story is not as rich as it could have been IMO.

To contrast, you can read if you like his “Household Monitor of Health” online: [link] When I did, I was surprised at the sheer volume of good practical common sense health advice in there. Sprinkled with absolute nonsense here and there, to be sure (“Effects of Drinking Ice-Water” chapter).

However, if it turns out he spurned Michigan Beet Sugar, then I’m afraid I’ll have to lower my estimation…

p.s. I should quickly add, since likely there are readers out there who know far more about JHK than I do, that I haven’t studied the man in depth. Heroes can have feet of clay, and my viewpoint might be naive. Still, I hope I don’t eventually learn that he was involved in some stock fraud scheme or some deliberate malfeasance. That would be…deflating.

Laura, It appears to be a majolica 19th century oyster plate for serving oysters on the half shell. There are indeed pottery companies here in the US, who do still make an all vitreous china modern version of these plates. One company, the Hall China Company of East Liverpool Ohio, has produced versions since the 1920′s. They are still in business today and were just sold to Homer Laughlin China Co., makers of the famous “Fiesta” dinnerware. Hall will still run independently though.