In the Archives: A Path Less Traveled By

Editor’s note: We live in a time where women, and men, can easily and safely navigate any woods filled with dangerous wild animals, say in a helicopter, armed with a hunting rifle. Think Sarah Palin. In simpler times, people walked through the woods. And they just hoped not to stray from the path, to find themselves in the company of a literal or figurative grizzly bear, or – as Laura Bien describes in this installment of her local history column – wolves.

In the early 1800s, thick forest covered much of the land south of Ypsilanti.

The virgin forest nourished huge flocks of passenger pigeons on migratory routes passing north. Often they passed low enough to be knocked from the air with sticks. After one such harvest, according to one Ypsilanti city history, “at dinner that day, there was a tremendous pigeon pot pie, sufficient to satisfy everybody, although there were twenty at the table.”

But the forest also held danger. One large swamp in Augusta Township was named Big Bear Swamp, and wolves and panthers roamed in our county.

Into this wilderness in 1828 came Andrew Muir with his family. They had fled an economic recession and spiking farm rents in Scotland and immigrated with other relatives to America. Members of the McDougall family also made the trip.

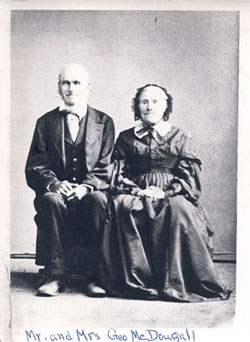

After the weeks-long Atlantic crossing, 26-year-old Mary Muir and 29-year-old George McDougall married in Rochester, New York on Halloween in 1828.

The families traveled by boat and overland to Michigan. Andrew Muir bought a small farm near the intersection of modern-day Stony Creek and Bemis roads, about 6 miles south of Ypsilanti. He invited his daughter Mary and son-in-law George to share the property. However George, who had worked as a miller back home in Ayrshire, chose to settle just south of the small Ypsi settlement and work at its flour mill there.

Mary often walked down to her father’s farm late in the week to see her parents and stay overnight. On Sundays, George would travel down to visit and he and Mary would return to their home.

One winter day, Mary prepared to visit her parents. She set the table for her husband and made sure his dinner was ready for his return from the flour mill. Mary adjusted her pretty new calfskin shoes, tied her plaid wool scarf over her dress, and left the house.

She set off on the faint Indian trail that wound through the six miles of forest to her parents’ farm.

The days were getting shorter and it was shady under the trees, but Mary knew she could reach her parents’ home before nightfall. Snow covered the forest floor, blanketing fallen logs and the crunchy layer of leaves.

In the distance, Mary saw it: an enormous fallen tree blocking the path. There was no climbing over it – she had to go off the path to find a way around.

The fallen tree trunk extended far into the surrounding trees. Mary picked her way to its end, working her way around. The afternoon light was fading.

On the other side, Mary searched for the path. That must be it – she set off again.

Mary walked on. This was odd – it was twilight and she should have been at her father’s farm. And the path looked strange. It dawned on her that at the fallen tree, she’d stumbled on a different path – one that was leading her into the wilderness.

Night was coming on. Mary guessed she must be close to her father’s farm and decided to leave the path. She picked her way through the forest. Under the dark treetops the snow glowed a soft white.

Some time later, Mary knew she was lost. She decided to return north to Ypsilanti and safety. Mary looked up through the bare branches and found the Pole star.

Mary pushed away branches and stepped over logs. The temperature was dropping. She glanced up at the star. Mary tripped and fell, scraping her shoe.

She ran a finger over the side of her shoe. She felt a rip where the stitching had split.

Mary was exhausted. She decided she would see better next morning. There was no help for it but to try and rest. She found a nook between a log and a tree trunk and sat down. She unfolded her shawl and draped it over herself, curling up on the frozen ground. Tiredness overtook her.

Mary’s eyes flew open and she sat up. Then she heard it again – a distant wolf howl. Silence. There it was again – and another. A third.

Should she run? She might fall again in the dark. Better to stay. Perhaps they didn’t know she was here. Was it near morning? Mary took out her husband’s watch and tried to read it. She hadn’t taken the key to wind it – it had stopped at one o’clock.

Hours later she saw a faint dawn light. She got up stiffly and began walking. The sun passed overhead. The rip in her shoe had widened, and the front sole slapped as she walked. The insole on the other shoe was fraying, letting in snow. It was late afternoon.

Mary heard a dog bark.

She altered her course toward the sound. Suddenly she came upon two cows in a clearing. Mary nearly collapsed with relief. She couldn’t see their farmhouse and couldn’t go any further. But the cows would return home for milking-time.

Mary propped herself against a tree, facing the cows. She dozed.

When she awoke, they were gone.

Mary jumped up and looked around. She heard a twig crunch and ran a few steps. She saw the flick of a tail among the twilight trees. Mary ran after it.

At the farmhouse three miles south of Saline and fifteen crow-miles from Ypsi, the farmers welcomed Mary. They fed her, tended her feet, and put her to bed. They told her that if she’d walked in a slightly different direction, she’d have been nowhere near a settled piece of land.

The next day, they drove her in their wagon back to Ypsilanti.

Sources: (1) Harvey Colburn, The Story of Ypsilanti, Ypsilanti Historical Society (reprint), 1923, p. 50; (2) Beakes’ “Past and Present of Washtenaw County;” (3) Chapman’s “History of Washtenaw County;” and (4) “An Incident of Pioneer Life,” Mary McDougall, published in the 1894 “Aurora” Eastern Michigan University yearbook.

Mystery Artifact

Last column’s Mystery Artifact featured a pot-like object with a rotating inner cylinder. Irene Hiebler correctly guessed that this is a coffee bean roaster. It was made in Ypsilanti in the 1870s or thereabouts by the Parsons Brothers. “Parsons Bros. is one of the most enterprising firms in the city,” reads an article in the September 21, 1878 Ypsilanti Commercial.

“They always have some new patent which they are about to try, and … the next new article of manufacture is to be a noiseless wind-mill … [they are also making] a cheap and easy spring bed … In 1873 Parsons Brothers sold $10,000 worth of washing machines … the greatest novelty, however, is the ‘O.K.’ coffee roaster.”

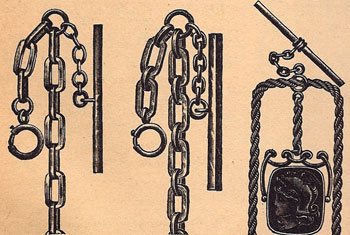

Today’s Mystery Artifact is something that Mary McDougall never owned. It’s likely Andrew Muir and George McDougall didn’t, either, though they may have liked to. What might it be? Take a guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Have an idea for a column? Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

Sneaking one in on a Saturday…

I’m guessing that it is a chain to secure your pocket watch to your trousers.

I think ABC is partly right. They do look like pocketwatch chains, but would a pocketwatch was usually carried in the vest pocket or coat pocket, and attatched to the vest or coat, not to the trousers.

I should not have embellished my answer. Yes vest. Sometimes it is hard to shake our 21st century perspective.

But then again if you wanted to attach your watch to your trousers it would still work. Or to your sweater…

In 1922, the UM Museum of Zoology published “The Mammals of Washtenaw County” as part of its Occasional Papers series.

This and all the UMMZ publications are freely available in pdf format from the University’s “Deep Blue” digital archive: [link]

The author, Norman Woods, was the son of an early settler, and he includes a number of stories of last sightings of large mammal species in our area. Most of the paper is a about the local landscape and small mammals like shrews and squirrels, but wolves, bears, mountain lions and elk are also covered. Among other things, Woods says that in the 1830′s, wolves were so destructive that it was hard to keep any livestock, and in 1853 the county was still paying bounties on wolves (though at the time there was frequently confusion between wolves and coyotes). He reports the last black bear having been shot in a marsh west of Saline in 1875 (though bears have been seen in the county in the last few years), and badgers were here until c. 1919. The last mountain lion was seen in 1870, and the last porcupine about the same time. Woodchucks were scarce until after settlement (they don’t like forest, so the clearing of the woods was good for them). There are no historical records of bison or elk, but several bison skulls were found just over the border in Jackson County, and elk antlers and bones (not fossils) have been found in the county. They, like beavers, may have been hunted out before there was much permanent settlement by European or American immigrants.

One surprising note is that the author (writing in 1921) says that white-tailed deer had been extirpated from the county by the late 1870′s. They certainly have made a comeback.

ABC: Sneaking one in due to the kindness of the C’s editors; I was backed up on another project, and was grateful to them for bumping the deadline. Anyways, are you sure this is not a marshmallow containment chain?

cmadler: Hmm, interesting guess. I wonder when wristwatches came into fashion.

George Hammond: Oh my, the “Deep Blue” archive is available to the public?

And there go my plans to decorate the tree tomorrow…

That is fascinating information you kindly typed in for us. Now, my understanding is that the “panther” I referenced is the same as a mountain lion that you mention, is that correct? I believe so. Bison remains in Jackson County!–that is remarkable! And elk strolling in Washtenaw…really interesting. I look forward to poring through the archive you kindly mentioned, and thank you!

If I recall correctly, wristwatches were widely considered only appropriate for women. I believe it changed in or shortly after World War I, when airplane pilots wore them out of necessity (because it would be too much to try to pull out a pocketwatch while flying a plane!), and no one was about to question their manliness. Once wristwatches became socially acceptable, they were quickly adopted in light of their convenience.

As an aside to this aside, I’ve seen some interesting discussion recently about the current decline of the wristwatch. Since most people carry cell phones, which display the time, there’s less need to wear a wristwatch in most cases, and I’ve heard that wristwatch use among young adults is declining precipitously.

“Oh my, the “Deep Blue” archive is available to the public?”

Much of the material is, but not all. Accessibility of particular items is up to the individual people and departments that put them there. The Museum of Zoology has made many of the papers in their two periodicals (the “Occasional Papers …” and “Miscellaneous Publications…”) available for free download. You can find lists of titles on the Museum website: [link]

They are organized by animal group, and then each paper’s number links to the pdf. Most of these are technical publications, of interest only to specialists, (e.g. “The myology of the pectoral appendage of three genera of American cuckoos,” “An Oligocene mudminnow (family Umbridae) from Oregon with remarks on relationships within the Esocoidei.”) but some of it will be of interest to local naturalists. Norman Wood’s 1951 “The Birds of Michigan”, all 591 pages, is there (it’s a big file, 25 Mb).

“Now, my understanding is that the “panther” I referenced is the same as a mountain lion that you mention, is that correct?”

yes. Historically, “panther” gets used for a variety of solitary big cat species by English-speakers around the world (mountain lions and jaguars in the western hemisphere, leopards in the east), but here in Michigan it would have referred to Puma concolor, aka mountain lion, aka puma, aka cougar. Prior to European settlement, this species was found from southeast Alaska east to the Atlantic and south all the way to southern South America.

“Bison remains in Jackson County!–that is remarkable!” Bison ranged across the southern part of the state, where the land cover was open enough, all the way to the western slopes of the Appalachians: [link]

“And elk strolling in Washtenaw” yeah, I like to think of an elk herd grazing in the oak opening that was where the diag is now. :-) Don’t get me started on the missing species, the mastodons browsing the swamps where the airport is, or the giant beavers eating cattail tubers in the shallows along Allen Creek, or the trout and the 6 foot sturgeons spawning in the Huron, or the flat-headed peccaries browsing on hackberry shoots along Stadium Boulevard…

That is very helpful extra information; thank you for taking the time to add it. It is always gratifying to hear from those with expert knowledge on the subject. I also was glad to learn about the flat-headed peccary. I had had no idea such a creature existed, but according to this website “the most common medium-sized mammal during the North American Ice Age.” (!)

Interesting to learn that there are still peccaries in the Southwest and that they are an indigenous American pig as opposed to the feralized European pigs that are wild in Michigan, the South, and some other areas. Neato!

Those do look like watch chains, although it’s hard to be sure without seeing the whole thing. The long rod goes into a buttonhole, the long chain leads to the watch, and the short chain holds the fob. The fob was originally a sort of handle for removing the watch from the pocket, but on these chains it’s strictly decorative.

uhm, i believe that they are called ‘fobs’. Watch fobs. And they are made to attach to the vestcoat, holding the watch in place, where it is secreted away in the vest pocket.

But I believe ‘fob’ is the proper name for it.

what is interesting, if you will notice, is that there are two types of clasp. One is a toggle clasp and the other, a spring ring clasp, which is interesting in that it means it is attached in two places and in two different fashions.

In the 19th century the “fob” was the pocket that the watch is carried in, and this item would have been called the “chain.”