AATA Finalizes Transit Plan for Washtenaw

Ann Arbor Transportation Authority board meetings (June 3 and June 16, 2011): The AATA board met twice in June – first at a special morning retreat held at Weber’s Inn on June 3 June 6, and again 10 days later for its regular monthly meeting.

Michael Ford, CEO of the Ann Arbor Transportation Authority, presents a possible board configuration for a countywide transit authority at the board's June 3 meeting at Weber's Inn. (Photos by the writer.)

On both occasions, a significant focus was the AATA’s countywide transit master plan. At the June 16 meeting, the board approved the final version of the first two volumes of the plan, which had previously been released in draft form. The two volumes cover a vision and an implementation strategy. A third volume, on funding options, is not yet complete.

The plan is the culmination of over a year of work by AATA staff and a consulting firm to perform a technical analysis and gather public input. The goal was to create a document to guide transit planning in the county over the next 30 years. The timing of the next step – beginning to translate a neatly formatted document into reality – will depend in part on a third volume of the plan, which has not yet been finalized. The third volume will describe options for how to fund expanded transit service in the county. Countywide transit funding will ultimately be tied to the governance structure of some entity to administer transit throughout Washtenaw County.

And governance is a topic that’s ultimately reflected in the actual wording of the resolution that the board adopted at its June 16 meeting on the transit master plan. The resolution authorizes transmittal of the documents not just to the public, but also to an unincorporated board, described as an “ad hoc committee” that will work to incorporate a formal transit authority under Michigan’s Act 196 of 1986. [AATA is currently incorporated under Act 55 of 1963.]

For the last few months, CEO Michael Ford’s regular monthly reports to the AATA board about his activities have included his efforts to meet with individuals and representatives of government units throughout the county to discuss participation in the governance of a countywide transportation authority. June continued that trend. So wrapped into this combined report of the AATA board’s last two meetings is a description of the June 2 visit that Ford and board chair Jesse Bernstein made to the Washtenaw County board of commissioners.

At its June 3 retreat, the board also voted to shift some funding to the AATA staff’s work associated with the countywide transit master plan.

At its June 16 meeting, the board handled some business not specifically related to the transit master plan. The board adopted two policies that it has previously discussed: one on the rotation of auditors, and the other on a living wage for AATA vendors. They also received updates on the expansion of service to the University of Michigan’s East Ann Arbor Health Center and to the Detroit Metro airport.

Progress on those two fronts led board member David Nacht to suggest that the kind of movement and progress the AATA was demonstrating, even without additional money that could come from a countywide funding source, showed that the agency’s future plans deserved support from the community.

Transit Master Plan (TMP)

At its June 3 meeting, the AATA board was asked to vote on a resolution endorsing Volumes 1 and 2 of its countywide transit master plan (TMP) as revised and amended. The plans had been previously released to the public at the board’s April 21, 2011 meeting.

A “whereas” clause in the board’s resolution provided some additional description of a transitional governance structure, which could lead to an eventual countywide authority established under Michigan’s Act 196 of 1986. The transitional structure would be “an interim and ’unincorporated’ Act 196 Authority Board (‘U196 Board’) which will act as an ad hoc committee to establish an organizational framework and funding base for an expanded transit system, and to work toward formally creating and incorporating a new Act 196 Authority.”

According to the resolution before the board, both volumes of the TMP are to be transmitted to the U196 board “for further analysis, refinement, and definition.” [.pdf of "Volume I: A Transit Vision for Washtenaw County"] [.pdf of "Volume II: Transit Master Plan Implementation Strategy"]

Michael Benham, project coordinator for the AATA’s transit master plan, told The Chronicle before the meeting that not much, besides revised formatting, had changed between the version of the plan disseminated to the public two months ago and the final draft. But he pointed to one substantive alteration that was made to one of the appendices, which describes a set of short- and medium-term enhancements the AATA hopes to make to the existing bus system. Those enhancements essentially involve the routing and timing of buses, as opposed to the construction of massive new infrastructure like rails or extra roadway lanes just for buses.

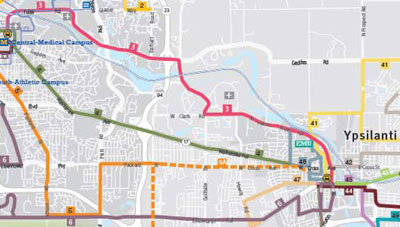

Between the time of the draft and the final version of that appendix, the strategy for serving the Washtenaw Community College campus and the St. Joseph Mercy Hospital has been beefed up. The initial draft looked like this:

Draft of planned bus network service enhancements between Ypsilanti and Ann Arbor, including the Washtenaw Community College and the St. Joseph Mercy Hospital. Route 3 is depicted in red. (Image links to larger file)

Between the draft and the final version, the same section of the map was revised to look like this:

Final version of map in appendix of the AATA transit master plan. Route 3 is depicted in green. Route 7 and Route 48 (an Eastern Michigan University shuttle) shoulder part of the ridership volume in the Washtenaw Community College and the St. Joseph Mercy Hospital area. (Image links to larger file)

Improvements in service that can be achieved in the shorter term – through route reconfiguration, increased frequency and extended hours of existing operations – are a theme that the AATA has tried to highlight through the transit master planning process. The idea is that existing service can be improved and additional services can be provided, before the establishment of a countywide authority.

During the June 16 meeting, the board heard from CEO Michael Ford, as part of his regular report, that the AATA would be extending its paratransit service to the University of Michigan’s East Ann Arbor Health and Geriatrics Center starting July 1, 2011. Ford also told the board that the target date for beginning some kind of bus service to the airport – likely by partnering with another provider like Michigan Flyer – is Oct. 15, 2011. The AATA is sticking with that target, even though the AATA’s grant application for federal Congestion Mitigation Air Quality (CMAQ) funds to support the airport service has been rejected.

In addition, the geographic boundaries for the Night Ride service have been extended out to Golfside Road.

News about service to the airport, the East Ann Arbor clinic and the Night Ride service led board member David Nacht to conclude that, “We’re making progress.” He ventured that the AATA was getting itself into a position where it could say to voters throughout the county, who may be asked to support a countywide authority with their tax dollars: Look what we’ve done without any additional funding – look at how we’re turning ourselves into a regional organization. We deserve some funding.

A comment from board chair Jesse Bernstein on the resolution that authorized dissemination of the final version of the TMP acknowledged that the next phase will be “very delicate.” He called the process so far “encouraging” in terms of communication with the community. The AATA will need to continue the values of open communication and discussion, he said.

Earlier in the meeting, Bernstein had responded to a criticism made during public commentary at a previous board meeting – that the AATA board did its work through committees, and did not do its work in the public eye – by laying out the structure of the board’s committees and how they work. The board has three committees: (1) performance monitoring and external relations (PMER); (2) planning and development (PDC); and (3) governance. The PMER committee is currently chaired by Charles Griffith; PDC is chaired by Rich Robben; the governance committee consists of the two committee chairs, plus Jesse Bernstein as chair of the board. Minutes of the PMER and the PDC are included in the board’s meeting packets, which are available to the public for download from the AATA website. The meetings themselves are also open to the public.

The unincorporated board of the new transit authority – called a “committee” and labeled “U196″ in the resolution – will be discussing how to incorporate the board and move forward, Bernstein said. The U196 will be making final recommendations, dotting i’s and crossing t’s. Bernstein said it is an exciting time to be on the board. He thanked the staff and those who have participated in the process so far and who will continue to participate.

Outcome: The board voted unanimously to approve dissemination of the first two volumes of the transit master plan and to convey it to the U196 board.

At the June 16 meeting, both people who commented during public time at the conclusion of the meeting were supportive of the board’s action on the TMP. Thomas Partridge saluted the board’s work on the plan, but encouraged board members to start using creative strategies for enlisting public support to help make bus stops more accessible.

Carolyn Grawi, of the Ann Arbor Center for Independent Living, echoed Partridge’s praise and also his suggestion about bus stop accessibility. She suggested that perhaps a visit to the Ann Arbor city council might be in order to address the intersection at Research Park Drive and Ellsworth, where Grawi has long advocated for a traffic signal. It would allow the AATA to run service in both directions in and out of Research Park Drive.

Countywide Governance

The resolution approved by the board at its June 16 meeting – which authorized dissemination of the transit master plan to the public and to the U196 board – was also considered by the board at its June 3 retreat. It was not approved at that meeting, mostly due to uncertainty about what that U196 board would actually be. To the eventually approved resolution, the following whereas clauses were added, to provide some general idea about the status of the U196 board:

WHEREAS, discussions have been held with locally elected officials within Washtenaw County for the purpose of establishing an organizational framework and funding base for such expanded transportation services, and

WHEREAS, those discussions are expected to result in the creation of an interim and “unincorporated” Act 196 Authority Board (“u196 Board”) which will act as an ad hoc committee to establish an organizational framework and funding base for an expanded transit system, and to work toward formally creating and incorporating a new Act 196 Authority, therefore …

In broad strokes, Michigan’s Act 196 of 1986 enables the establishment of public transit authorities that include multiple jurisdictions in a single geographic area – cities, townships, villages – but has a provision for political subdivisions to opt out of inclusion in the transit authority.

Countywide Governance: Two Acts – Act 55 and Act 196

The AATA now operates under Act 55 of 1963. Current discussion has focused on the possibility of forming a countywide funding base through creating a public transit authority under Act 196 of 1986. [Previous Chronicle coverage lays out in detail some of the other technical differences between Michigan’s Act 55 (1963) and Act 196 (1986): "AATA Gets Advice on Countywide Transit."]

One advantage to Act 196 (if any type of “fixed-guideway” system is envisioned) is that it allows for voters to approve the levy of a millage lasting up to 25 years for transit service that includes a fixed guideway. Vehicles that run on rails – street cars and commuter trains – are obvious examples, but bus rapid transit (BRT) is also a fixed guideway system. With a BRT operation, special reserved lanes and queue-jumping infrastructure at intersections allow buses to take priority over other traffic on the roadway, so that they have a fixed guideway within the roadway.

Another advantage of Act 196 is that it offers more administrative flexibility for the formation of a public transit authority. Act 55 enables cities to establish a transit authority. While it’s possible to subsume additional multiple jurisdictions in an existing Act 55 public transit authority, there is little flexibility for opting out.

For Act 196, a county counts as a political subdivision that can establish a public transit authority under the act. And that’s what the AATA would like Washtenaw County to do, if the county board of commissioners is willing to take that step. But there are other options for forming an Act 196 authority, which include the formation by an existing Act 55 authority, or by multiple political subdivisions who choose to band together under an intergovernmental agreement.

On any scenario for formation of an Act 196 public transit authority, the flexibility for inclusion or exclusion in that authority is one possible advantage of using Act 196 for expanded countywide service in Washtenaw County. An Act 196 authority allows for political subdivisions of the county that do not wish to participate in a public transit authority to opt out. And those political subdivisions can opt out without eliminating the opportunity for other political subdivisions to band together to provide public transit for their residents.

Countywide Governance: Third Act – Act 7

The initial indication is that Salem Township is not interested in participating in a public transit authority for Washtenaw County. In Michael Ford’s monthly written report to the board for June 2011, he notes:

In a disappointing development, Salem Township voted not to participate in the Northeast Group for the time being. However, we will not be deterred. We will revisit Salem when Northfield Township votes in July and continue to update them before the U196 board starts meeting.

The other members of the “Northeast Group” to which Ford’s memo refers include Northfield Township, Ann Arbor Township and Superior Township.

On the scenario the AATA has sketched for eventual Act 196 authority board membership, the Northeast Group would have one of 15 seats on the Act 196 authority board. Of the four political subdivisions in the Northeast Group, Ann Arbor Township and Superior Township have already struck an agreement made under Act 7 of 1967 – which establishes how interlocal governmental agreements are made. That agreement may, as Ford’s report indicates, be joined by Northfield Township in July.

Countywide Governance: Interim Unincorporated Board – U196

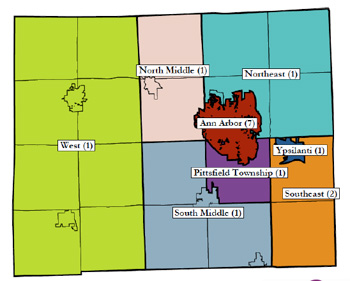

The Northeast Group is part of a possible governance structure for an Act 196 authority that the AATA has sketched out for the county. It blocks out the county into nine geographic sections corresponding to a total of 15 board seats. Seats would be assigned partly based on population, and partly on the funding used.

Possible composition of board membership for a Washtenaw countywide transit authority. (Links to larger image.)

The sketch envisions a scenario where Ann Arbor’s existing 2 mill tax would remain in place, in addition to whatever countywide millage might be enacted, and so assigns Ann Arbor seven board seats. Based purely on population in the county, Ann Arbor would receive one-third of the board seats – that is, only five.

Concerns about the proportionality of representation as well as the proportionality of benefit have been raised not just by those outside of Ann Arbor, but by Ann Arbor residents looking at a future countywide system from a broader point of view.

At the June 3 AATA board retreat, during public commentary Vivienne Armentrout told the AATA board she felt that if she were in an out-county area, she’d wonder about proportionality of funding compared to benefits. She asked: “Are we talking about massive investment in commuter rail?” Without having funding options on the table, it’s not clear what you’re asking people to buy into, she told them. [Armentrout is a former member of the Washtenaw County board of commissioners.]

In the rest of the county, the reaction to AATA’s possible Act 196 board representation has also met with some skepticism and resistance. On a second visit to the Washtenaw County board by representatives of the AATA, the different perspectives – among commissioners representing Ann Arbor districts in the county and those representing other areas – were readily apparent.

Countywide Governance: Visit to Washtenaw County Board (June 2)

In April, staff from the AATA and the Washtenaw Area Transportation Study (WATS) had made a presentation at a working session of the county board of commissioners, giving details of tentative plans for the countywide transit system. Some commissioners raised concerns at the time, particularly related to a possible governance structure, which designated seven seats to Ann Arbor on a 15-member transit authority board. From The Chronicle’s report:

Commissioner Kristin Judge, whose district covers Pittsfield Township, protested the way board seats were assigned, saying it gave an unfair advantage to Ann Arbor. Commissioner Wes Prater, who represents southeast portions of the county, said he was “flabbergasted” that the governance plan had been developed so fully without consulting the county board, which under the current proposal would be asked to ratify the new transit authority’s board members. However, some individual commissioners were previously aware of the proposal, including board chair Conan Smith and Yousef Rabhi, chair of the board’s working session. Both Smith and Rabhi represent Ann Arbor districts.

The topic was taken up again at a June 2 county board working session, which included a presentation to county commissioners by AATA CEO Michael Ford. Ford and Jesse Bernstein, chair of the AATA board, also fielded questions about the proposal, covering a range of topics – from the number of seats on a governing board to whether Ann Arbor residents would continue to pay their current transit millage.

After Ford’s presentation, Dan Smith kicked off the discussion by noting that at their retreat earlier this year, commissioners had talked in general about the county government taking a leadership role in coordinating countywide initiatives. He clarified that at this point, the governance structure is just a proposal, and might be changed in the future. Ford confirmed that this is the case, saying it would ultimately be up to local governments as to how they form a transit authority’s governance. AATA is just trying to facilitate the discussion, he said.

Rob Turner wondered what the county’s role would be. Is it necessary for the county to incorporate the authority, as the proposal calls for? No, Ford said – but that would be the easiest way to handle it, rather than having multiple units of government file for incorporation separately.

Turner asked what additional role the county would play. That’s up to commissioners and the county administration, Ford said. If the county wants to take on additional responsibility, it’s possible to explore that, he added – possibly some kind of liaison role would be an option.

Turner then asked how the proposed governance would be affected if a smaller group of communities wants to form an Act 7 partnership. For example, right now the proposal calls for an Act 7 formed from jurisdictions on the entire west side of the county – including eight townships, Chelsea and Manchester. What if only a portion of those entities wanted to form an Act 7? Turner asked. How would that affect the transit authority’s governance structure?

Ford said they hadn’t faced that issue yet. All of the local governments had indicated agreement with the proposed plan and its geographic breakdown, he said. If that changes, he added, adjustments would be made. [Later in the month, Salem Township's board voted not to participate, though AATA still hopes they'll eventually join the authority.]

Finally, Turner clarified that if a local entity doesn’t opt out within a 30-day period after the vote to incorporate as an Act 196 authority, they’d be joining for five years. That’s true, Ford said – it’s specified in Act 196.

Wes Prater asked why AATA couldn’t incorporate under Act 196, rather than the county. That would be an option, Ford said. Prater expressed concern that the county would seem to be accepting liability and responsibility for the transit authority, but wouldn’t have any power over it – as proposed, no county representative would have a seat on the authority’s board, for example. It didn’t seem like the transit authority would answer to any elected body, Prater said.

Prater also objected – as he has in the past – to the way that seats on the transit authority board would be assigned. It’s not a one-person, one-vote structure, based on population, he noted. Rather, Ann Arbor would get seven of the 15 seats, even though the city’s population represents a third of the county. The remaining eight board members would be representing two-thirds of the county’s population. ”That doesn’t add up to the one person, one vote in my mind,” Prater said.

Ford noted that Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti would bring assets (buses, bus stops, and buildings, for example) to the new entity – and that both cities already have dedicated transit millages. He said AATA’s attorney had reviewed the proposal, and that they’re confident that the way they’re proceeding is sound.

Prater wanted the county to have its attorney check the proposal as well. If it approved the Act 196 incorporation, the county board would be authorizing an entity that in turn could put a tax levy on the ballot, he said. The governance proposal really bothers him, Prater said.

Bernstein said Prater had raised some core questions that will have to be answered. The board of the unincorporated Act 196 entity will be the people who decide how the transit authority will be governed, he added – it isn’t set in stone. The issue of how many representatives from Ann Arbor serve on the unincorporated board is wide open, he said.

The AATA is suggesting this as a point to start the discussion, Bernstein told commissioners, but there’s plenty of room for modifications and adjustments. They’re not ready to propose something definitive.

Prater again cited concerns over creating a transit authority that doesn’t report to any government entity. He said he’s very cautious about supporting an authority that might put a countywide tax on the ballot. Prater expressed support for the model used in Grand Rapids, in which a smaller number of jurisdictions form the transit authority. He guessed that most areas in Washtenaw County, outside of the urban areas, don’t have the population to support a countywide transit system.

Bernstein reported that in talking with people in the county’s rural townships, they are concerned over the ability of residents to age in place – that is, to continue to live in their homes, even if they can no longer drive. Elected officials in those areas, he said, want transit services for residents to get to their medical care, for example.

The other issue is land use, Bernstein said. Townships don’t want dense developments in their communities – they’d rather see transit corridors, he said, so that their tax base can grow while they preserve farmland and open space at the same time.

Bernstein said it’s true that there’s not yet a funding plan, though organizers assume it will be a millage of some sort. There’s still a long way to go, he said.

Prater noted that five townships and two cities account for about 75% of the population in this county – those are areas where he supports public transportation. [He was referring to the cities of Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, and the townships of Ypsilanti, Scio, Superior, Pittsfield and Augusta.] Prater said he’s not convinced that the approach being pursued is the right one, adding that he’s very critical of it. If the governance isn’t fair, the initiative is already in trouble, he said.

Leah Gunn clarified that each jurisdiction involved in the transit authority would vote separately on a transit tax. She noted that Ann Arbor residents have been paying 2 mills for transit for many years – it was voted in as a permanent millage in the 1970s, and funds the AATA. Will that millage be retained, even if there’s an additional millage?

That’s one of the suggestions, Bernstein said, adding that he’s open to whatever makes sense. Some have said that every jurisdiction should pay the same amount. All of these things are decisions that need to be made. ”I have no idea what that [funding mechanism] is going to look like,” he said.

Gunn said she feels strongly that Ann Arbor should keep its 2-mill transit tax. She elicited from Ford that Ann Arbor has invested nearly $180 million in its transit system over the years. In addition, they’ve leveraged those dollars for millions more in federal funding, she noted. Ann Arbor has been very generous, she said – without that investment, AATA wouldn’t be able to provide transit services to other communities, like Ypsilanti.

Yousef Rabhi clarified that whatever future millage might be voted on would be on the ballot only in jurisdictions that wanted to be part of the new transit authority – it wouldn’t necessarily be countywide. He also pointed out that based on having one-third of the county’s population, Ann Arbor would be entitled to five seats in a 15-member transit authority board. But if the city also contributed an additional 2 mills in funding, that could justify an additional two seats on the board, he said.

Rabhi said he’d like to keep the 2-mill transit tax, noting that he uses the AATA bus system frequently. With a larger system, it’s an opportunity for more routes, more services – more of a good thing, he said.

Ronnie Peterson weighed in, telling Ford and Bernstein that a countywide system has been a long time coming. He had urged AATA’s previous two CEOs to take on this project, but they hadn’t, he said. He wished it had been undertaken when the economy was better. “Keep your foot to the pedal,” he told them.

Peterson urged Ford to bring communities to the table that already buy transit services from AATA, like Ypsilanti and Ypsilanti Township – communities which Peterson represents on the county board. That should happen even before a formal entity is created, he said.

Bernstein concluded the discussion by noting that the next major step will be to pull together representatives into an unincorporated entity, and to develop articles of incorporation for an Act 196. Meanwhile, AATA will continue to operate its current system, he said, and they’ll work to get answers to the questions that commissioners have raised. Where they wind up must be inclusive of everyone who wants to participate, Bernstein added – they won’t return to the county board until everything is in order.

Countywide Governance: Funding, TMP Volume 3, U196

One next step is the actual creation of the U196 board, now described as an “ad hoc committee.” The membership on the U196 board is not proposed by the AATA to be the same as the eventual Act 196 authority board. In fact, at the June 3 board meeting was a resolution that would have authorized the chair of the AATA board, Jesse Bernstein, to appoint three members of the current AATA board to serve on the U196, not all seven board members.

The board did not vote on the resolution, but did discuss it long enough to establish the rationale behind not appointing more than three: Action by the U196 board should not be construable as actions of the AATA board. [Four members would constitute a quorum of AATA board members.] Bernstein was keen to emphasize that the U196 board would be open, welcoming and transparent to all.

Another next step for the AATA is to complete Volume 3 of the transit master plan, which would focus on funding options. Existing funding options include fares, advertising (on vehicles), state and federal grants, and property taxes if approved by voters. Possible future funding options identified by the AATA include local vehicle taxes, gas taxes or sales taxes. Those would require state-level legislative action.

A resolution that was before the board, but was not voted on, at the June 3 meeting was one that would release “Volume 3 – Funding Options Report” to a “panel of financial and public funding experts, to review, refine and adjust the document” before it is forwarded to the U196 board.

To take the next steps will also require more funding for planning – though not on the same scale as for the future transit system. Before the board at its June 3 meeting was a resolution that decreased the budget for AATA administrative salaries and benefits by a total of $200,000 and made a corresponding increase in line items supporting the effort of transportation master planning – for agency design fees, consulting fees, printing and production and media.

Outcome: The board unanimously approved the budget change to support additional planning work.

Regular Business (June 16): Living Wage Policy

At its June 16 meeting, the board considered a living wage policy that is roughly parallel to the living wage policy expressed in the city of Ann Arbor’s city code. It applies to the wages paid by AATA contractors to their employees. The AATA living wage policy would apply to contractors who have a contract worth more than $10,000 per year and employ or contract with more than five people. It would apply to nonprofit contractors only if they employ or contract with 20 or more people.

The minimum wage to be paid to their employees by AATA contractors would be at the same level stipulated by the city of Ann Arbor. In May 2011, the city ordinance on the city’s living wage – keyed to poverty guidelines – required that the wage be nudged upward. The new wage is set at $11.83/hour for those employers providing health insurance, and $13.19/hour for those employers not providing health insurance. That’s an increase from previous levels, which have remained flat at $11.71 per hour for employers offering health insurance and $13.06 per hour for those who don’t offer health insurance.

The AATA board had initiated the process of setting a living wage policy at its Dec. 16, 2010 meeting, when it passed a resolution directing staff to explore that policy. The context for that resolution was a janitorial contract for the Blake Transit Center. Board member Rich Robben had expressed concern that a vendor might be achieving an extraordinarily low bid by paying its workers substandard wages.

During the brief deliberations by the board, David Nacht characterized the policy as reflective of community values, but still sensitive to very small employers. It shows the AATA doesn’t believe in slave labor or undervalued labor, he said.

Sue McCormick clarified what in cases where the AATA has current contracts in place, they’ll continue as they are. But she gave the example of the auditor, where there’s an annual contract renewable each of five years. On renewal each year, the living wage policy would apply.

Outcome: The board voted unanimously to adopt the living wage policy.

Regular Business (June 16): Auditor Rotation Policy

Also at its June 16 meeting, the board considered a new auditor rotation policy. The policy would entail that the AATA not use the same auditor for longer than two four-year terms – a total of eight years.

Sue McCormick, who also serves as the city of Ann Arbor’s public services area administrator, was the board member who originally suggested looking into the issue of implementing an auditor rotation policy. She had raised the issue at the board’s Sept. 16, 2010 meeting, when board members approved a contract with Rehman as its auditor, but only for one year.

Among the risks cited by the AATA in adopting the rotation policy were the potential for needing to hire an auditor with less experience, who would produce a lower quality of work, and the potential that competitive bidding would be restrained. Among the benefits cited by the AATA in adopting the rotation policy were independence, a fresh approach, and lower cost.

At the board’s May 19 meeting, Charles Griffith, chair of the board’s performance monitoring and external relations (PMER) committee, had indicated to his colleagues that the policy would need to come before the board at its June meeting so that there would be time to issue a request for proposals in time for next year’s audit.

In reporting out from PMER at the June 16 meeting, Griffith said the idea of limiting an auditor to eight years of service had received McCormick’s blessing.

Outcome: The board voted unanimously to adopt the auditor rotation policy.

Next Board Meeting: Hoists

Although the board does not have a July meeting scheduled, CEO Michael Ford indicated that he would likely ask them to meet that month, in order to approve some capital improvements to the AATA maintenance facility – bus hoists, used to lift buses so that mechanics can work underneath them. A possible date floated at the June 16 meeting was Monday, July 18.

Present (June 3, 2011) : Charles Griffith, David Nacht, Jesse Bernstein, Sue McCormick, Rich Robben, Roger Kerson, Anya Dale.

Present (June 16, 2011) : Charles Griffith, David Nacht, Jesse Bernstein, Sue McCormick, Roger Kerson, Anya Dale. Absent: Rich Robben.

Next regular meeting (tentative): Monday, July 18, 2011 at 6:30 p.m. [confirm date]

Purely a plug: The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of publicly-funded entities like the Ann Arbor Transportation Authority. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

The primary transportation system in the county, private owenership of automobiles, gets enormous subsidies at the Federal level. I don’t see how AATA can succeed with this plan if it must get millage approval individually from every community in the service area. But I wish them luck.

Re (1), as I understand it, it would be approval of inclusion in the service area by each community (the Act 7 business), but the millage vote would be county-wide. So if the millage passes, even residents of a township who voted overwhelmingly against the millage, as long as the township had agreed to be included in the service area, would be required to pay it. (And could also participate in the service.)

What does “queue-jumping infrastructure” mean? Buses leaping over cars and pedestrians?

Queue-jumping infrastructure would involve changes to traffic signals so that buses could override the light cycle and go through without stopping.

This is described in the Ann Arbor Transportation Plan Update (adopted by the Council in 2009) thus:

“Evaluate and construct queue-jumping lanes (Washtenaw between I-94 and Platt; Ann Arbor-Saline at I-94 and Eisenhower; Maiden Lane/Fuller/Geddes; Plymouth and I-94; Plymouth/Murfin”

The tentative price tag at that time was about $9 million for all these intersections together.

Re: [3] queue jumping “Buses leaping over cars and pedestrians?”

That’s actually not far off. Think: buses cutting over to a special reserved lane just at an intersection, so that if there are other vehicles waiting at a light, the bus will be able to advance to a position at least even with the other traffic waiting for the light to change. It’s also possible to time the light so that the bus gets green a few seconds before everyone else so it can leapfrog over the traffic it used to be behind. There’s some lane schematics and more words here: [link]