In the Archives: A Postmaster’s Gamble

Editor’s note: Laura Bien’s column this week features two aspects of modern culture that a hundred years from now may have completely disappeared from the landscape: newspapers and the regular mail delivery. The battle she describes – between the press and the postmaster – is ultimately won by the postmaster.

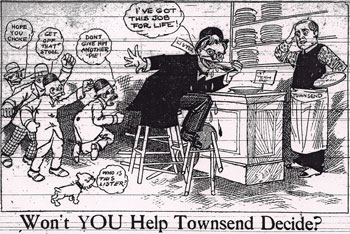

Overnight, he’d become the most hated man in Ypsilanti. A series of editorials in the Ypsilanti Daily Press condemned his actions and character. The paper even published a jeering cartoon, among large headlines detailing his disgrace.

William Lister wasn’t a murderer, rapist, or adulterer. With his wire-rimmed glasses and prim expression he resembled a rural schoolmaster or Sunday School teacher, both of which he had been. But his steady gaze hinted at a steely character with greater ambitions, which was also true. In the fall of 1907, William tangled with one of the most powerful groups in town, risking his reputation and his lucrative government job on a matter of principle.

William Noble Lister was born in a log cabin in Iosco township in Livingston County on the last day of 1868. His cabinetmaker father drowned when William was two. William’s mother Frances remarried and the family moved to Ypsilanti in the spring of 1882.

In 1887 William graduated from Ypsilanti High School. For a year, he taught in a rural school in Livingston County’s Unadilla. He returned to Ypsilanti to obtain his teaching degree from the Normal teacher training college. After another stint as a teacher in the western Upper Peninsula, William became Saline school superintendent from 1891 to 1895 – a first step to greater things.

In 1895, William operated a Saline drugstore with Benjamin Sheeder. Near the end of his four years at Lister and Sheeder’s, William became the Washtenaw county commissioner of schools. One of his reforms for Washtenaw schools was adopted statewide, and under his leadership the number of county school libraries increased from six to 108.

William also gained prominence in Saline’s local group of Masons, winning its highest office, “Worshipful Master.” He represented the lodge at state Masonic conventions. He also became a member of the Ypsilanti Masons, the Knights of Pythias, and the Maccabees. This wide web of connections, and William’s interest in Republican politics, would in time serve him well.

Despite his success as school commissioner, William chose to reenter business life in 1903, becoming president of Ypsilanti’s Reed Furniture Co. Producing a variety of popular wicker furniture shipped across the country, the company was a growing concern.

Though the Reed Furniture Company promised to be profitable, in about a year William sold – or was persuaded to sell – his interest in the company. The Ypsilanti workers, who had been earning roughly $1.60 a day [about $38 today], were fired and the factory was moved to Ionia. Inmates of the Ionia State House of Correction now made the furniture, working over 9 hours a day for 50 cents.

Reed worker trade groups protested. “Reed goods manufacturers in Michigan, following the example set by the Michigan Broommaker’s Union, are preparing to oppose the use of convicts in the State penal institutions there,” said an article in the December 27, 1906 Wooden and Willowware Trade Review. The contract with the Ypsilanti Reed Furniture Company should be dissolved, said the article, as it violated state law.

Their protest was fruitless.

The new Reed Furniture Company owner was Fred Warren Green. A graduate of the Ypsilanti Normal School and the University of Michigan law school, Green served as Ypsilanti city attorney. His political ambitions led him to become mayor of Ionia in 1913, treasurer of the state Republican party in 1915 and a decade later, state governor.

In the spring of 1904, William was appointed Ypsilanti postmaster by Michigan Republican congressman Charles Townsend, originally of Jackson. At the time, although regular clerks in the post offices across the state got their jobs by taking civil service exams, the position of postmaster was appointed by the political party then in power. It was regarded as a plum job with easy indoor work and a fat federal salary, and was often fiercely fought over.

Grumbling about William’s appointment was heard in Ypsilanti from local Republicans who regarded him as an upstart, not someone who’d earned the privilege of postmaster after years of service to the party, much less someone who’d lived in town for very long or invested much into the city. “The proposed appointment . . . is a big surprise to people of [Ypsilanti],” said one Washtenaw paper, “and it is said to be the result of a [hunt] on the part of a few politicians managed by Committeeman Prettyman of Ann Arbor . . . Mr. Townsend has been made to think that Mr. Lister was the whole cheese at Ypsilanti.” Prettyman would himself become Ann Arbor postmaster two years later.

“The people of Ypsilanti are well pleased with the announcement by Congressman Townsend,” said one Ann Arbor newspaper. “This choice evidently meets the approval of all . . .”

In 1907, resentment in Ypsi boiled over.

That fall, the Ypsilanti Masons were raising money for a new lodge, their Michigan Avenue quarters having become too small. After rejecting one spot on Washington Street, they chose a North Huron Street lot. It was expensive, so the fraternal order decided to hold a huge fundraising event – a three-day bazaar featuring entertainment, food, and donated goods for sale.

Comprising local merchants and businessmen, the group was influential in town. Hundreds of donations came in from storekeepers and private citizens. One shipment of 250 cigars even arrived from Detroit. A local widow donated a golden watch that her departed husband, a onetime Mason, had given her. Her gracious letter was printed in the paper.

The bazaar kicked off on Nov. 7. Huge crowds thronged the event housed in the onetime Light Guard Hall on Michigan Avenue above the present-day Mix boutique. The hall was filled with booths selling everything from clothing to guns. Baas and clucks emanated from the livestock room, and Madame Cheiro read palms. Tickets were sold for a prize drawing. Each night musical programs were presented and the Order of the Eastern Star, the Masons’ women’s auxiliary, prepared large banquets, one chicken pie supper serving over 200 people.

The Nov. 11 Ypsilanti Daily Press printed a list of the prizes attendees had won over the course of the bazaar. F. Kibler won a diamond ring, Tracy Towner snagged the buffalo robe, and Mrs. Mary Wilson won the heaviest prize, a ton of coal. An accompanying story praised the Masons for their good work. The group had netted $1,500 [$35,000 today], reported the paper, with more than $300 from the culinary efforts of the Order of the Eastern Star.

The newspapers were printed and bundled. Those headed for rural subscribers were addressed and brought to the post office on North Huron at 5:30 p.m. The post office stood across the street from the North Huron lot that the Masons wanted. Similarly, the postmaster and the Masons were about to face off against each other in battle.

William refused to deliver the papers.

Two days later a Nov. 13 headline in the Ypsilanti Daily Press blared, “Postmaster Lister Administers Insult to Phoenix Lodge.” None of the rural subscribers had received their Nov. 11 edition of the Press. “Lister’s action, when it became known today, was roundly scorned by prominent local businessmen. They styled it the smallest, meanest, and most contemptible piece of work they ever heard of.”

The problem had been the Nov. 11 article listing the prize winners. The innocuous news that Mrs. George Gaw had won a ham, William Ellis a pair of trousers, and Will Duratt an “owl cushion” had not passed muster with the postmaster. He had no animus towards owl cushions. The problem lay in the prize drawing being too similar to a game of chance.

According to the Comstock Act, no obscene material could be delivered via U.S. mail. The act prohibited the mailing of items relating to contraception, abortion, or other topics deemed immoral or lewd – including gambling. Even private sealed letters came under the purview of the Act, all the more a front-page newspaper story describing a “gambling” event at a Masonic fair.

“Who is this Lister?” bellowed the Nov. 13 Press. “W. N. Lister, a rank outsider, a man who but recently floated into town; a man who didn’t have a dollar invested here; who was a citizen of Ypsilanti scarcely in name, had contrived to get himself appointed to the office,” said the article. “Republicans who had labored here for 20 years for the good of the town and the party; who had given of their time and money, were passed over for this fellow.” William’s political connections, the article said, were the only reason for his appointment.

The newspaper launched a smear campaign that depicted William as the smug holder of an undeserved sinecure. The Nov. 15 paper published tearful accusations from one Widow Barnes, who alleged that William had driven her husband Charles, the former deputy postmaster, to an early death. William had kept the office too cold, the paper quoted her as saying, causing her husband to catch pneumonia and be confined to his home. After demands from William that Charles return to work at once, he died in the post office at his desk.

There is some evidence that William was a demanding boss. He opened the post office six days a week at 6:30 a.m. and kept it open until 7 at night. He even opened it for an hour on Sunday mornings instead of giving his staff of 8 clerks and 22 mail carriers a day off.

The Nov. 20 Press published an editorial cartoon depicting William as devouring his “first term [as postmaster] pie” while chortling, “I’ve got this job for life!” In December, the Press continued the campaign. A story in the Dec. 2 paper, “How Mr. Lister Discriminates,” claimed that a Detroit paper contained a description of a “Yankee Circus in Egypt” to be put on by Detroit Masons. The event was nigh identical to the Ypsilanti bazaar, said the article, yet William allowed this item to cross his desk unhampered. Unfair!

“The postmastership is the softest snap in Ypsilanti,” continued the article. “The salary is $2,600 a year [about $60,000 today]. When Lister completes his four-year term, he will have drawn more than $10,000 [$231,000 today] – a fortune to most citizens” – especially in 1907, considering that year’s financial panic. The paper urged citizens to contact Congressman Townsend urging him to rescind his appointment – or at least not renew William’s term for another four years.

There were plenty of “Reasons Why Masons Are Sore,” said a Dec. 16 story in the Press. A former Ypsi resident living in Washington D.C. had sent the Press a Washington newspaper detailing a Masonic prize giveaway. “It is very interesting to members of Phoenix lodge,” said the article, “that a paper published in Washington, under the very eyes of the postmaster general, could circulate its papers, when the [Press] was held up here by ‘Grand Mogul’ Lister.”

The paper’s appeals to sway the congressman, which continued up to the end of 1907, were in vain. William retained his position, and became the first postmaster in Ypsilanti history to secure a second term. He married Detroit teacher Sarah Hutton, bought a home in the midtown area, and had two children, Frances and William.

Over time, feelings against William seemed to abate. By 1916 he was city treasurer and served on a county road board. In 1938 he was honored at an oratory festival at Normal College, as a former star orator.

The protests of an entire town had not dislodged the resolute and resourceful postmaster. The former teacher had done his homework.

Reader-Submitted Mystery Artifact

Last column’s artifact drew a number of correct guesses.

“Its a woodworker’s scribe tool,” said ABC. Cosmonican also knew. It was a delight to learn that this tool is still in use in modern form today.

This week’s Mystery Artifact is special as it is a reader-submitted Mystery Artifact, a fun feature which I’d like to include in this column as often as possible. Do you have innumerable cool old tools/machines/doodads lying around? Why not take a picture and send it to ypsidixit@gmail.com and I’ll include it as soon as possible. See if you can stump other readers!

This object certainly stumped me. Had I not been told what it is, I simply would never have guessed. What might it be? Perhaps it’s not exactly what it seems …

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and “Hidden History of Ypsilanti,” which was released Oct. 6, 2011. Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our publication of columnists like Laura Bien. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

Its a wedge for splitting marshmallows.

Seriously I have no idea. Neither side appears to be hand-friendly and neither side appears to want to be struck by a hammer. I am stumped. Laura, is this to be used in conjunction with another tool? (Yes, that’s the same as asking for a hint.) Don’t answer though as I would like to see if someone will get this without help

Hi ABC, no, to my knowledge (according to what I was told) this is not used in conjunction with another tool.

Your first comment reminds me of all of the ridiculously/wonderfully specialized utensils there used to be among wealthier Victorian-era folk. Bon bon scoop, fish slicer, crumbers, butter pick, mustard spoon, egg spoon, grape scissors, pickle castor, tomato server, cheese scoop, asparagus fork, lettuce fork, berry fork, fish fork, melon fork, bacon fork (yes, a fork for bacon only)….here are more by Victorian-era silvermaker Reed & Barton.

Perfect site for fitting out your table if you don’t mind paying $50 per piece.

I think Alton Brown refers to those things as single-taskers, or something like that.

So I looked again, and this is a guess but… it looks like it belongs on a construction site more than in your Victorian dining room so I am going to say it is a wedge to hold bricks apart while crafting an arch.

Like the Slap-Chop, the no-mess bacon cooker, or the Banana Peeler (“Pops the top, no mess, no mush!”

Interesting guess…it does look like it means business…and turns out it does!

I’m guessing the mystery object is some type of old railroad tool. Used to lay track or prep railroad timber. Just a remote guess though.

Dave: It certainly looks like an old RR spike, to be sure. But perhaps this object has a more sinister use.

At first glance it looks like it’s used for prying or wedging something. Snuff box opener? But the “handle” end doesn’t really look like a handle, it looks functional.

There is something stamped on the side of it, maybe letters.

I’m kinda’ leaning towards a door stop, or maybe a meat tenderizer? Easier than that stick of dynamite / bucket of water combo I mentioned once.

Jim: There are indeed “letters” stamped along the side of this article. I wonder what language they are from? “Snuff” is closer than you might think.

Could be kanji or Chinese. A fan?