Sustaining Ann Arbor’s Environmental Quality

Ann Arbor city staff and others involved in resource management – water, solid waste, the urban forest and natural areas – spoke to a crowd of about 100 people on Jan. 12 to highlight work being done to make the region more environmentally sustainable.

Matt Naud, Ann Arbor's environmental coordinator, moderated a panel discussion on resource management – the topic of the first in a series of four sustainability forums, all to be held at the Ann Arbor District Library. (Photos by the writer.)

It was the first of four public forums, and part of a broader sustainability initiative that started informally nearly two years ago, with a joint meeting of the city’s planning, environmental and energy commissions. The idea is to help shape decisions by looking at a triple bottom line: environmental quality, economic vitality, and social equity.

In early 2011, the city received a $95,000 grant from the Home Depot Foundation to fund a formal sustainability project. The project’s main goal is to review the city’s existing plans and organize them into a framework of goals, objectives and indicators that can guide future planning and policy. Other goals include improving access to the city’s plans and to the sustainability components of each plan, and to incorporate the concept of sustainability into city planning and future city plans.

In addition to city staff, this work has been guided by volunteers who serve on four city advisory commissions: Park, planning, energy and environmental. Many of those members attended the Jan. 12 forum, which was held at the downtown Ann Arbor District Library.

The topics of the forums reflect four general themes that have been identified to shape the sustainability framework: Resource management; land use and access; climate and energy; and community. The Jan. 12 panel on resource management was moderated by Matt Naud, the city’s environmental coordinator. Panelists included Laura Rubin, executive director of the Huron River Watershed Council (and a member of the city’s greenbelt advisory commission); Kerry Gray, the city’s urban forest and natural resource planning coordinator; Jason Tallant of the city’s natural area preservation program; Tom McMurtrie, Ann Arbor’s solid waste coordinator, who oversees the city’s recycling program; and Chris Graham, chair of the city’s environmental commission.

Dick Norton, chair of the University of Michigan urban and regional planning program, also participated by giving an overview of sustainability issues and challenges that local governments face. [The university has its own sustainability initiative, including broad goals announced by president Mary Sue Coleman last fall.]

The Jan. 12 forum also included opportunities for questions and comments from the audience. That commentary covered a wide range of topics, from concerns over Fuller Road Station and potential uses for the Library Lot, to suggestions for improving the city’s recycling and composting programs. Even the issue of Argo Dam was raised. The controversy over whether to remove the dam spiked in 2010, but abated after the city council didn’t vote on the question, thereby making a de facto decision to keep the dam in place.

Naud said he’s often joked that the only sure way to get 100 people to come to a meeting is to say the topic is a dam – but this forum had proven him wrong. The city is interested in hearing from residents, he said: What sustainability issues are important? How would people like to be engaged in these community discussions?

The forum was videotaped by AADL staff and will be posted on the library’s website. Additional background on the Ann Arbor sustainability initiative is on the city’s website. See also Chronicle coverage: “Building a Sustainable Ann Arbor,” and an update on the project given at the November 2011 park advisory commission meeting.

Sustainability & Resource Management: Setting the Stage

Dick Norton, chair of the University of Michigan urban and regional planning program, began the panel presentation by saying that he’d been asked to talk about the big picture concepts related to these themes, and challenges that local governments face in dealing with them. He emphasized that the concept of sustainability encompasses more than just the environment, but that this first forum would focus on environmental issues.

Dick Norton, chair of the University of Michigan urban and regional planning program, and a member of the Huron River Watershed Council executive committee.

Norton gave a brief overview of possible ways to think about attributes of a clean environment, related to topics that would be discussed by panelists. For air and water quality, it’s important that those resources are unpolluted, available in sufficient quantity, and that residents have adequate access. Viable ecosystems are one way to provide clean air and water, he said. Ecosystems provide filtering functions, and are a source of biodiversity – we suffer if we homogenize our environmental base, he said. Ecosystems also provide an aesthetic quality, making places pleasant to live.

Regarding responsible resource use, Norton pointed to the three Rs: Reduce, reuse, recycle. Recycling is good, he said, but reuse is better and reducing is the best approach to responsible resource use. It’s also important to think about the waste stream, and how waste can be used as input for new systems. Composting is one example of that.

Norton then outlined four challenges that local governments face when dealing with these issues. The first is factual uncertainty. The world is complex, and there is a great amount of scientific uncertainty. That gives people ammunition to argue against environmental protection, he said. There’s uncertainty over when a substance becomes pollution, for example. Carbon dioxide or arsenic are common elements – at what amounts do those elements become pollutants? Another uncertainty relates to resource depletion. The environment is a resilient receptor, Norton said – it can take a lot of shock to its system. But at what point does disruption and depletion of resources become too great? That uncertainty makes it difficult for government to act, he said.

Moral disagreements are another challenge for governments, Norton said. Is nature a form of sacred life, or just toilet paper on a stump? Should nature be preserved at the expense of jobs? And who gets to decide? Norton said he tells his students that if you have a collaborative planning process, you’ll encounter a plurality of values. That’s a challenge.

Capacity problems – both legal and financial – are also an issue, Norton said. Local governments are creatures of the state, he said, and can only do what the state enables them to do by law. A lot of local officials are reticent to undertake proactive environmental protection, but they have a lot more capacity to act than they think, he contended.

Regarding fiscal capacity, Norton noted that financial resources are highly strained, and there’s a sentiment that local governments can’t afford this “sustainability stuff.” But Norton argued that energy efficiency, for example, is often less expensive in the long term, though it usually requires a higher upfront investment. He encouraged officials to make decisions based on a longer timeframe.

The final challenge Norton cited is a category he called “unhappy propensities” – localism, parochialism and inertia. Localism is the attitude that “we get to decide,” he said. Parochialism is the belief that if something is happening outside of our borders, we don’t need to worry about it. That works if the problems are downstream, but not so much if it’s an upstream problem headed our way.

Then there’s the challenge of inertia: We’ve always done it this way, so why change? Norton noted that sustainability is a different way of looking at things, and that means change. Ann Arbor is stepping out in front of other communities, Norton said, and is pushing these boundaries. He encouraged a broader perspective, looking at decisions as they fit into a bigger system.

Water Resources: Protecting the Huron River

Laura Rubin, executive director of the Huron River Watershed Council, began by describing the history of HRWC. The nonprofit was founded in 1965 by 17 communities along the Huron River who were concerned about protecting this water resource. They knew they couldn’t just look at it from the perspective of where the river flowed through their individual jurisdictions.

Sometimes people overlook the value of the watershed, Rubin said. In addition to providing drinking water, the river also is an asset for recreation, property values, wildlife habitat and stormwater control. The watershed – including the Huron River and its tributaries – is arguably the region’s largest natural feature.

The Huron River is the only river in southeast Michigan that’s a state-designated “natural river.” The designation affords the river special protections, she said, related to development and vegetation. The watershed also is protected by strong local and regional regulations and partnerships, Rubin said, citing the Huron Clinton Metropolitan Authority as one example.

The watershed offers a wealth of recreational and fishing opportunities, Rubin said, and provides a habitat to threatened and endangered wildlife, including the northern madtom, the snuffbox mussel, the prairie fringed orchid, the least shrew, and the massasauga rattlesnake.

But although the Huron River is the cleanest urban river in Michigan, she said, there are also problems. Many sections are classified as “impaired,” based on the inability to meet certain uses, like swimming or fishing, as laid out in the federal Clean Water Act. Two major problems are excess levels of phosphorus and E. coli – a problem that’s especially common in urban areas, Rubin said. Sources for E. coli include animal and human feces, which can be discharged into the river from wastewater or sewer overflow during storms.

Other problems causing the impaired classification relate to sediment, erratic flows, low dissolved oxygen, mercury and PCBs.

Rubin outlined several broader threats to the area’s water resources. The region, sandwiched between the urban areas of Detroit and Lansing, has lost many of its natural areas, she said. Ann Arbor itself has become more urbanized, which has contributed to the loss of habitat, as well as to pollution, warmer temperatures and erratic flows.

Hydrologic changes are another threat. The river has 97 documented dams, Rubin said, and this changes flow patterns tremendously. It leads to the loss of wetlands, causes sedimentation, and alters the way that the ecosystem functions.

Rubin also identified “non-point” source pollution as a threat to the watershed. As rain falls onto roofs, into gutters, and onto roads, it collects pollutants that eventually flow into the river. That’s the No. 1 cause of water pollution in the U.S., she said.

A variety of tools are used to address these issues, Rubin said, including watershed-wide partnerships, data that’s collected and analyzed, advocacy and education. Due to efforts by the watershed council and the University of Michigan, the Huron is one of the best studied rivers in Michigan, she said.

The watershed council pushes people to do more to protect the river, Rubin said. Staff and volunteers work on water-quality monitoring, for example, as well as an adopt-a-stream program, which includes data collection and experiential learning.

There’s value in having “eyes on the river,” Rubin concluded. Among other things, it enables the long-term tracking of trends, and provides a scientific basis to advocate for local and state protection policies.

Following Rubin’s presentation, Matt Naud asked the audience a trivia question: How many cities use the Huron River for their drinking water? Just one – Ann Arbor, he said. That’s why the city cares about its upstream partners.

Solid Waste: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle

Tom McMurtrie, the city’s solid waste coordinator, began by saying that recycling is one of the most effective things that people can do to reduce their carbon footprint. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has identified Ann Arbor as one of the nation’s top recycling communities, he said. So how did the city get to this point?

From left: Kerry Gray, Ann Arbor's urban forest & natural resource planning coordinator; Jason Tallant of the city's natural area preservation program; and Tom McMurtrie, solid waste coordinator.

In the 1970s, the city brought curbside recycling to every home in the city, McMurtrie said. Back then, recycling required more work – residents had to separate green glass from brown glass, cardboard from newspapers. It reminded him of a favorite New Yorker cartoon: “Recycling in Hell.”

In 1991 the city introduced two-stream recycling. And every multi-family building was added, which doubled participation. The city built a sorting facility at the location of the current drop-off site.

Then in 2010, McMurtrie said, the city moved to another level of recycling: single stream. New plastics were added to the list of recyclables, and new carts with radio-frequency tags were deployed, which allowed single-family homes to record their recycling and be eligible for a rewards program.

In mid-2010, a $3.5 million overhaul was completed to the city’s materials recovery facility – known as the MRF (pronounced “murf”)– at 4150 Platt Road. Overall tonnages of recyclables have tripled, he said, with materials coming from as far away as Toledo and Lansing. Four new hybrid recycling trucks were purchased, which use less fuel. Four more hybrid trucks will likely be added in 2012, he said.

McMurtrie also pointed to the concepts of “reduce” and “reuse.” His suggestions included shopping for fresh food at the farmers market, where less packaging is used, and using reusable bags whenever possible. About two years ago, the city also added the option of including food waste in its composting program, he noted. Every pound of food or yard waste that’s composted greatly reduces the burden on landfills, he said.

Showing images extracted from a core boring taken at the closed Ann Arbor landfill, McMurtrie noted that most materials in the landfill haven’t decomposed.

McMurtrie concluded by saying that the city is working on an update of its five-year solid waste plan, and he encouraged residents to participate by giving their input. The first meeting will be held on Thursday, Jan. 19, 2012 from 4-6 p.m. in the 4th floor conference room in Larcom City Hall, 301 E. Huron. The meeting is open to the public.

Urban Forest Management

Kerry Gray, the city’s urban forest and natural resource planning coordinator, said that until recently, the city didn’t have a comprehensive understanding of its urban forest resources. In 2009, city staff finished an updated tree inventory, cataloging location and maintenance needs, among other things. The city has 42,776 street trees, 6,923 park trees (in mowed areas), and 7,269 potential street planting locations, she said.

Maintenance needs were also inventoried, with 1,642 trees identified as priority removals and 3,424 trees that needed priority pruning. An additional 43,271 trees needed routine pruning, and 1,362 stumps needed to be removed.

In 2010, the city completed an evaluation of its urban tree canopy, Gray reported. The canopy covers nearly 33% of the city. Of that, 46% is located in residential areas, 23.7% is in the city-owned right-of-way, and 22% is in recreational areas, such as parks. Compared to other cities, Ann Arbor’s tree canopy is average, she said.

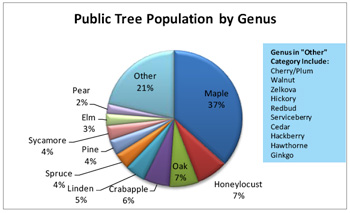

Gray addressed the issue of tree diversity, and said the city discourages the planting of maple trees, which account for 37% of the public tree population. ”Plant something other than a maple – that’s my take-away message,” she said.

Ann Arbor’s urban forest is a tremendous asset, Gray said. Public trees provide an estimated annual $2.8 million in benefits related to energy, property values, stormwater control, air quality and other benefits.

But in the past, there hasn’t been a management plan for the urban forest, unlike the city’s other assets, Gray said. So in 2010, city staff began developing an asset management plan, with the goal of maintaining the urban forest and maximizing its benefits. The city is doing a lot of public engagement related to this plan, she said – more information is online at a2.gov/urbanforestry.

Matt Naud added a coda to Gray’s presentation, noting that the city lost about 10,000 city street trees that were attacked by the emerald ash borer several years ago. The city spent over $2 million just to remove the trees, he said, and that doesn’t count what it cost residents for tree removal on private property. That’s why tree diversity is important – you don’t know what’s coming next, he said.

Natural Area Preservation

Jason Tallant of the city’s natural area preservation program (NAP) began his comments by showing a slide of the Furstenberg Nature Area – it’s the image he sees when he closes his eyes to think about the topic of sustainability, because it integrates the built environment with the native landscape.

NAP straddles the line between providing services for people, he said, and empowering them to preserve natural features in the city’s parkland and on their own property. He read NAP’s mission statement: “To protect and restore Ann Arbor’s natural areas and foster an environmental ethic among its citizens.”

Ann Arbor resident David Diephuis, center, talks with urban forester Kerry Gray, left, and Jason Tallant of the city's natural area preservation program.

A lot of sustainability practices are based on history, Tallant said, specifically what occurred prior to European settlement. He quoted from the 1836 land survey notes of John M. Gordon, who described the land between Ann Arbor and Dixboro: “Oaks of the circumference of 9-15 feet abound in the forests… White Oak and Burr Oak at intervals of 30-40 feet with an undergrowth 5-6’ high which has the appearance of being annually burnt down as I am informed it is.”

The history of the land is really important when thinking about how to move into the future, Tallant said. He showed a slide of the types of vegetation on land in the Ann Arbor area prior to settlement, and noted that much of the area had been covered by a mixed-oak or oak-hickory forests, with wetlands along the river. It wasn’t a monoculture, he noted, but rather a mixed environment, depending on topography, hydrology, soil type and other factors.

NAP facilitates restoration work in all of the city parks and natural areas, Tallant said. Their work includes conducting controlled burns, taking detailed inventories of the plants and animals within the city, and knowing what’s occurring in the landscape. They also do invasive species control, he said – when you see someone walking along with an orange-colored bag full of garlic mustard, they’re restoring the land so that its biodiversity isn’t diminished. That work helps create a resilient ecosystem, he said.

Outreach, Education

Chris Graham, chair of the city’s environmental commission, said he hoped that the previous speakers had given the audience an idea of the extraordinary things that Ann Arbor is doing related to sustainability. Residents should be very proud, he said.

Graham explained that the original “Ann’s arbor” was a grove of large burr oak trees – the “children” of those early oaks are obvious in the area near St. Andrew’s Church, he said, north of city hall. Underneath those oaks were roughly 300 species of plants that the native Indians burned every year.

Just a few decades ago, there were no regulations related to landmark trees, Graham noted. Controversies in the 1970s and ’80s, when development resulted in the removal of many of those trees, led to changes in Chapter 62 of the city code – what’s known as the natural features ordinance, Graham said. Ann Arbor stepped up courageously, he said, and added a natural features standard that must be met in order to gain site plan approval for any development.

What are natural features? Graham asked. His list includes woodlands, native forest fragments, some wetlands, waterways, and floodplains. Related to native forest fragments, Graham said there’s an idea hatching to develop a stewardship program, similar to the city’s natural area preservation program. The new program would look at native forest fragments in all parts of the city, including the University of Michigan and private land – the fabric of natural features knits itself across the city, he said. The plan would be to do outreach and education, so that property owners would know what’s in their back yards.

The children of trees that existed in the 1820s won’t last without help, Graham said. “Come join us in this endeavor.”

Questions & Comments

During the last portion of the forum, panelists fielded questions and commentary from the audience. This report summarizes the questions and presents them thematically.

Questions & Comments: Recycling

Question: Why doesn’t the city’s recycling program accept No. 3 plastics or biodegradable materials?

Tom McMurtrie noted that No. 3 plastics – made from polyvinyl chloride – are a significant contaminant if mixed with other plastics. The city needed to be responsible, he said, and fortunately there aren’t a lot of No. 3 products in the waste stream.

As for biodegradables, McMurtrie said that’s been a challenging issue. On the surface, it looks like a good idea, he said. However, research shows that biodegradable products break down into very small particulates that aren’t necessarily good for the environment. Most of the particulates are petroleum-based, he said, and end up staying in the environment in that form. The other issue is that if those particulates end up in the recycling stream, they act as contaminants.

Question: Are there plans to eventually accept post-consumer food waste? And how much contamination ends up in the compost stream?

McMurtrie fielded this question too, inviting the speaker to participate in the city’s solid waste plan update. This issue of post-consumer food waste will be explored, although there are some repercussions around that issue, he said. Regarding contamination in the compost stream, that hasn’t been a problem, McMurtrie said. The city switched to a private operator about a year ago, and it’s worked out well, he said. [At its Dec. 6, 2010 meeting, the city council approved contracting with WeCare Organics to operate the city's composting facility.]

Question: If reducing waste is really the goal, how will incentives be built into the program to achieve that goal? There are incentives to recycle, but how can the city encourage reduction?

McMurtrie called this a great question, and said that a simplistic approach might be to use a graduated fee system for trash collection – to charge more for large trash containers, and less for smaller ones. The city is already doing that to some extent, he said. Households that use 96-gallon trash containers pay a fee each year – $38 – while there’s no fee for 64-gallon or 32-gallon containers. Perhaps the city could incentivize more in that area.

Jeanine Palms asked city staff about whether there are plans to give incentives to residents for reducing their waste, not simply for recycling it.

Jeanine Palms, who had asked the original question, wondered if there was any way to charge for the actual amount of waste that a household produced. McMurtrie replied that it’s an option, but that city council has been hesitant to take that approach. It risks becoming a kind of regressive tax on low-income people with large families, he said.

Dick Norton weighed in, saying that the answer depends on what you want to reduce. Palms’ question and McMurtrie’s answer had focused on trash, he said, but there are other things that people consume, like energy, water and land. Urban planners try to design cities to create greater density and transportation systems so that people can live more compactly. The ways that cities are built out impacts how much people consume, he said.

Norton also pointed to research on the impact of monetizing behavior. One study looked at a daycare center, which started charging parents who showed up late to pick up their kids. The intent was to create a disincentive for people, and to eliminate the late pick-ups. But instead, more people started showing up late, Norton said. When a monetary amount was attached to that behavior, people decided it was worth the amount charged. So incentives can result in perverse outcomes, he noted.

We have to start changing our cultural expectations, Norton continued. We have to stop thinking about living the big life, then throwing it away later. And that’s a tougher nut to crack, he said.

Chris Graham pointed to another thing that could be reduced: Turf grass. The amount of energy, pollutants, time and effort that’s spent on maintaining lawns in the city is counterproductive when trying to achieve sustainability, he said.

Laura Rubin addressed the question from the perspective of water resources. She noted that the city has a graduated water rate structure, so that heavier users pay more. The Huron River Watershed Council have been holding focus groups on the issue of water conservation. Because water is plentiful in the Great Lakes region, the issue of saving water isn’t always compelling. It’s better to tie the issue to energy conservation, she said.

When people talk about reasons why they might want to save water, the knee-jerk answer is to save money, Rubin noted. But when asked, no one in the focus groups could report what their water bill is, she said. Rubin concluded by noting that while our culture seems to be driven by money and economics, other motivations are often at play.

Matt Naud pointed out that information on water consumption per household is available on the city’s website. Residents can get a lot of data about their water usage by typing in their address and water bill account number, he said.

Comment: Portland, Oregon, has mandated that residents compost their food waste – that’s a direction that Ann Arbor should be headed. Currently, compost pick-up in Ann Arbor runs from April through December. I still eat fruits and vegetables in the winter – compost pick-up should be year-round.

Matt Naud encouraged the speaker to participate in the city’s solid waste plan update, saying that this type of feedback is exactly the kind of thing the city needs to hear.

Question: I live in an apartment in order to be environmentally sound. When will food compost pick-up be available for multiple family dwellings? I now take my food scraps to friends who live outside the city and raise chickens. So there’s no lack of motivation.

Matt Naud again suggested that this kind of feedback would be useful for the city’s solid waste plan update. Tom McMurtrie said that most multi-family buildings can get compost carts. Requests can be made by calling 99-GREEN.

Questions & Comment: Air Quality – Fuller Road Station

Question: The proposed Fuller Road Station will be a parking structure with almost 1,000 spaces that will bring 1,000 cars into an area near Fuller Pool and Fuller Park. It seems like this will affect the air quality along the Fuller Road corridor and the Huron River. It’s already a heavily used traffic corridor with a lot of emissions, and it seems like Fuller Road Station would really change the quality of air.

Matt Naud said he wasn’t sure if a formal air-quality study has been completed for the Fuller Road Station project. He offered to contact Eli Cooper, the city’s transportation program manager, and find out what’s being done or what the plan is.

Questions & Comment: Water Quality – Argo Dam

Comment: I was really surprised to see the number of dams along the Huron River. Fred Pearce wrote a book called “When the Rivers Run Dry.” He has almost nothing good to say about dams.

Laura Rubin noted that there are 97 documented dams along the Huron River – until recently there were 98, but one was removed in Dexter. Beyond that, there are at least 50 other dams that the Huron River Watershed Council has discovered while taking inventory for a new dam management tool it’s developing. A lot of the dams are connected to aging infrastructure, she noted – used at former wastewater treatment plants, or to generate electricity. Some dams have been retired from their original uses. Some are just piles of rubble.

Dams are very detrimental from an environmental point of view, Rubin said, but socially they can be very successful. They can have recreational value. For the Huron River, flood control isn’t a problem, so dams aren’t generally needed for that purpose, she said. A lot of river systems and social systems have been engineered, she noted, and it’s hard to change that mentality.

Dick Norton said the issue highlights the fact that “green” and “nature” don’t have the same meaning for everyone. Norton, who’s on the executive committee of the Huron River Watershed Council, noted that the council was involved in discussions about whether to remove Argo Dam, and it had been painful. [The watershed council advocated for dam removal.] A lot of people who would typically be on the same side of an environmental issue were on different sides of the Argo Dam issue, because they valued natural resources in different ways, he said. The debate was emblematic of issues that society struggles with, he added. Norton said he sympathizes with local officials, who get hammered by people on various sides of an issue.

Questions & Comment: Public Outreach

Comment: I’ve been a townie since 1967 – and have been to a lot of the concerts that are in the posters hanging around the room. [The concert posters were part of a retrospective organized by the Ann Arbor District Library called "Freeing John Sinclair."] Outreach needs to go much further.

My neighborhood is concerned about the Gelman 1,4 dioxane plume, and about property values. Very few of my neighbors are paying attention to other issues that were mentioned tonight. They don’t want taxes to go up, or property values to do down, and they don’t want to pay more for a trash cart. They need to understand sustainability issues in ways that make sense to them. I’d like to see more outreach.

Matt Naud acknowledged that outreach is a challenge. Funding for this kind of effort is one issue – many people who work on sustainability issues are funded by grants, and “that’s not sustainable,” he said.

Questions & Comment: Land Use, Natural Areas – Library Lot

Question: Will the city have a public conversation about the future use for the top of the new underground parking structure – the Library Lot? A lot of people would like to see a park or green space there. Is the city going to ask for ideas from the public?

Matt Naud asked city councilmember Sabra Briere – the only elected city official who attended the forum – to comment.

Briere noted that early last fall, at the city council’s direction, the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority began to explore alternate uses of the five city-owned parcels in downtown Ann Arbor. Those parcels include the Library Lot on South Fifth Avenue north of William; the former YMCA lot north of William between Fourth and Fifth avenues; the Palio lot at the northeast corner of Main and William; the Kline lot on Ashley north of William; and the bottom floor of the parking structure at Fourth and William.

This is a plan that hasn’t been developed yet, so no one can say what will happen, she said, but part of the plan will be to solicit public input. In the near term, she said, the Library Lot will be a surface parking lot, with trees planted. That’s not the long-term plan, she said. However, Briere added, no one knows how long the near-term will last.

Dick Norton commented that there’s a need to see how to make urban environments more green, but it’s also important to worry about maintaining farmland outside of the city. Development should go into already developed cities – it’s important to think about how to accommodate more people in urban areas so that large tracts of farmland and forest can be preserved outside of cities. It’s a difficult trade-off, he noted, especially because different jurisdictions are involved, and different perspectives. Residents of the city don’t want it to change and grow bigger, while farmers don’t want to be told that they can’t sell their land for development – in many cases, that’s their retirement plan.

But if the city wants to reduce energy and preserve farmland, turning the Library Lot into open space probably isn’t the best use for it. The site should probably be put to a more urban use, Norton said. It’s something to think about.

Matt Naud noted that at one of the future sustainability sessions, the city’s greenbelt program will likely be included. [Laura Rubin of the Huron River Watershed Council is a member of the city's greenbelt advisory commission, which oversees the greenbelt program. The program, funded by a 30-year millage, preserves farmland and open space outside of the city by acquiring property development rights.]

Comment: Some years ago, we dug out the grass on our lawn extension and replanted it with native plants – and we were ticketed by the city. The city needs to straighten out that disconnect.

Jason Tallant of the city’s natural areas preservation program applauded the planting of native plants in the easement. Some residents are putting in rain gardens or bioswales, which is great, he said. But the key point, he said, relates to public safety. If the plantings obstruct the view – of pedestrians using a crosswalk, for example – that’s a problem. That’s why the city enforces height restrictions on plants in the easement, he said. The thing to remember is “the right plant for the right place.” [The height restriction limits vegetation to an average height of 36 inches above the road surface.]

Questions & Comments: Future Forums

Question: It was interesting to hear about what the city is doing, but this forum didn’t match my expectations. I thought you’d have more opportunities for asking questions and engaging in dialogue. As I decide whether to attend future sessions, I wonder if the format will be the same?

This is an experiment, Matt Naud said. The first forum was intended to give people a taste of what the city is doing toward sustainability in different areas – city staff are never quite sure how much information is getting out, he said. The question is whether to hold longer sessions, to give the public more time to ask questions and give commentary, or to hold smaller focus sessions that take a deeper dive into these issues.

Naud said the city staff would like to hear what kind of format would be most effective – feedback forms were provided at the forum. Basically, if people want a certain kind of meeting and will attend it, the city will hold it, he said.

Naud said he’s held public meetings about the Gelman 1,4 dioxane issue and only a dozen people would come. It’s hard to know what issues will draw a turnout. He said he’s often joked that the only sure way to get 100 people to come to a meeting is to say the topic is a dam – but this forum has proven him wrong, he said. The city wants to know how people prefer to give feedback, and how this discussion should move forward, Naud said.

Future Forums

Three more forums in this sustainability series are planned. All forums will be held at the downtown Ann Arbor District Library building, 343 S. Fifth Ave. starting at 7 p.m.

- Feb. 9, 2012: Land Use and Access – including transportation designs, infrastructure, land uses, built environment, and public spaces.

- March 8, 2012: Climate and Energy – including an overview of Ann Arbor’s climate action plan, climate impacts, renewable and alternative energy, energy efficiency and conservation.

- April 12, 2012: Community – including housing, public safety, public art, recreation, outreach, civic engagement, and stewardship of community resources.

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public entities like the city of Ann Arbor. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

Relevant to the University of Michigan’s sustainability efforts, UM released its 2011 sustainability report on Jan. 16, with metrics on energy use, waste reduction, alternative transportation use and several other measures. A .pdf file of the report: [link]

My sense that “Sustainability” is merely a code word for “Real Estate Devlopment” has not been altered by the report of this meeting. There are many pretty words about “The Environment”, and “Recycling”, but in the end, it’s only about “The Varsity”.

Detroit is the core of SE Michigan. With that in mind, development in Ann Arbor IS sprawl.

“Sustainability”, in a non-cynical context, is about not needing to import outside resources to sustain life. As presented here, however, “Sustainability” is only about the “Need” to import more people.