In the Archives: Helping the Deserving Poor

Editor’s note: Laura Bien returns this month after a three-month hiatus from her In the Archives column for The Chronicle. Look for it in the future around the end of every month. For this column, she reviewed around 1,500 pages worth of meeting minutes from the Ypsilanti Home Association.

Nellie Smith* heard someone coming up the stairs and sat up in bed. She could see her breath in the late-winter afternoon light. Perhaps he had left something behind. She glanced around the room. There was nothing on the table, the chair, or the stove with the broken leg propped on a brick.

Knocks sounded. Nellie stood, shook out her ragged nightgown, and opened the door an inch. The friendly gaze of a middle-aged woman in a trim winter coat and long dark skirts met Nellie’s cautious look.

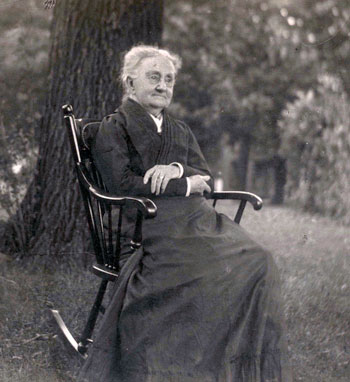

Harriet Gilbert as she looked around the time she was first elected Ypsilanti Home Association president in 1875, an office she held for over 30 years.

Lizzie Swaine introduced herself, apologized for the intrusion, and said there’d been word of a little difficulty at this Washington Street address. It felt cold here, she said – did Nellie have any fuel in the house? No, said Nellie, nor food either. Lizzie asked a few more questions, reassured her that help was coming, thanked her for her time, and left. Likely the women’s interaction was similar to this imagined scene.

What is a matter of record is that some days later Lizzie joined twelve other women for the May 1896 Ypsilanti Home Association meeting at Lovina Briggs’ Huron Street home. As Lizzie described Nellie’s plight, she may have noticed some raised eyebrows. The ladies discussed the case. Later, Association secretary Cleantha Dickinson paraphrased the talk in the 1896 meeting minutes logbook.

“Mrs. Swaine came to present the case of Mrs. Smith,” she wrote, “whom she found without a fire and about to be turned out of her rooms because she could not pay her rent.”

She continued, “Investigation among the ladies proved that the woman had a father and brother in comfortable circumstances who would not help the woman unless she behaved herself … it was found that she had been under arrest for keeping a disorderly house,” a euphemism referring at that time to prostitution.

She concluded, “The ladies decided they could not help her while she persisted in wrong doing.” Luckily, Nellie was an exception – the group helped most of those cases that came before it.

Long before federal or state social welfare agencies, the Ypsilanti Home Association was a homegrown ladies’ charity group founded in 1857 as an auxiliary of New York’s American Female Guardian Society, which operated a “Home for the Friendless.” Any woman could join the YHA for five cents [a little over a dollar in today’s money]. Schoolgirls could also join, and were exempted from the fee if they sewed one garment to give to the “Home.” The first donation box mailed to New York contained a variety of handmade clothing and bedding, and some beans.

Initially held in members’ homes and later in various Ypsi churches, the afternoon meetings began with a Bible reading and prayer, followed by roll call and member reports of needy cases. Two women from each of Ypsilanti’s then-five wards composed the executive committee, which undertook home visits and had the authority to distribute donations.

In addition to donations sent to New York, the ladies also assisted the poor in Ypsilanti. In 1863 the group chose a closer-to-home beneficiary, the “Detroit Home of the Friendless.” Seventeen years later, the YHA decided that the Detroit group was self-sufficient. Thereafter the Association’s energies turned exclusively to the Ypsi poor.

Over the decades, the YHA’s help took many forms. Shoes were purchased for a child who could not attend school barefoot in the winter. The ladies made numerous bedsheets and comforters. The group took charge of distributing Thanksgiving food donated to Ypsi churches. One meeting was held with the ladies sitting around a rectangular quilt frame, sewing as they listened.

The YHA distributed firewood, winter coats, furniture, and jars of homemade jam. They graciously thanked area farmers for donations of vegetables. They accepted 126 loaves of bread from a city-wide baking contest. During the Civil War, the YHA sent items to the Soldier’s Aid Society. They even paid for a length of sidewalk in front of the home of a man who couldn’t afford the city-assessed cost.

They asked the city council to supply a better grade of coal for the municipal free allotment to the poor, unsuccessfully. On another occasion, they approached the council again, this time with a formal petition requesting that the city’s scrap wood, offered to the poor as fuel, be sawed into stove lengths instead of four foot long chunks, to save the recipients the cost of taking it to a sawmill. They succeeded.

It seems a small victory, but the ladies of the YHA were exercising their collective social power in one of the few ways then viewed as appropriate for women. They had no vote, limited rights, and access to only a very few types of female employment regarded as acceptable. Given these societal constraints, the YHA offered Ypsi women a means of effecting change in their community and gaining authority and influence within the vehicle of Christian charity.

In an era that drew a sharp distinction between privation caused by misfortune versus questionable morals, the ladies of the Association withheld their charity on occasion, as in Nellie’s case. In the fall and winter of 1888-89, they refused help to the Moffett family, Jane Wesson, and a Mrs. Gordon, for unrecorded reasons. At the February 1892 meeting “the ladies made a vigorous protest against assisting a family where the father of the family was able to work.” The member who had given aid was Lura Parsons, who again met with disapproval at the March 1894 meeting. Lura reported that she had given money to a recent arrival from northern Michigan. The other ladies declared “the man was wholly unreliable and unworthy of assistance. Mrs. Parsons was [demoted] to only assist in case of hunger or sickness.”

This friction was rare in the group’s decades of good works, at least judging by the surviving minutes. The majority of meetings were productive and upbeat. One acclaimed president elected in 1875, Harriet Gilbert, retained the office for over three decades.

The YHA won community respect early in its long tenure. Within a year of its founding, schoolchildren, Normal (Eastern Michigan University) students, merchants, farmers, and residents began to channel donations of goods and money to the YHA.

Recognition also came through visits by such distinguished guest speakers as local and Detroit ministers. In July of 1864, even Sojourner Truth gave a talk to the group. The visit was a stop on her train trip from her Grand Rapids home to the White House, where the former slave met Abraham Lincoln. Her direct, impassioned manner of speaking may have been a bit overpowering to the YHA ladies. “Judging from observation,” noted the meeting minutes, “some present thought ‘distance’ would have lent ‘enchantment to the view.’”

Later, after years of experience, the group seemed to regard the local poor with a proprietary attitude. When one family’s home burned down in the fall of 1907, neighbors showered the family with money, furniture, and clothes. This irked the YHA. In the October 9, 1907 Ypsilanti Daily Press, an open letter from the association urged the community to “end the indiscriminate giving, especially of money … [instead, to the YHA’s executive committee] may be sent either a notice of contributions … or the things themselves.” It didn’t help that the family’s father had a vague but troubling connection to a recent Huron River drowning.

Active during the Depression, the YHA played a major role all over town in helping with or coordinating such projects as preserving food or making clothes. The group was shocked when in 1935 President Roosevelt introduced new legislation, including the Social Security program, that would federalize social welfare programs, to be administered top-down by the states.

The State of Michigan demanded that the YHA submit papers to Lansing proving that the group had been disbanded. The YHA debated what to do, and a read between the lines suggests that their initial response seems to have been polite yet strategic stalling.

By the April 1935 meeting the group could stall no longer. “In regard to our dissolution papers,” reads the title to one section of the 1935 logbook, “A motion was made by Mrs. Weber and seconded by Miss Minor that a personal talk with the Secretary of State might be more effective than correspondence. She moved that we drive over to Lansing and settle matters.”

And they did. Like many other local charities, the YHA worked out an agreement whereby they could continue their charity work, even as federal funds flowed in. The group lasted until just after World War II, when the YHA reduced its meetings to only two a year. It apparently disbanded in 1946.

For nearly a century the YHA had spearheaded charity work in Ypsilanti. The thousands they helped had good meals, warm clothes, and a bit of relief and hope thanks to the association’s enduring efforts.

*Surnames of charity recipients have been changed.

Mystery Artifact

In the previous column, cmadler correctly guessed that the object in question was a nutcracker.

It really doesn’t work very well, though, which may be why only one person recognized its purported function.

Those little plier-like crackers are far better.

At any rate.

This column’s mystery artifact is a recent acquisition by the Ypsilanti Historical Museum. I stumbled upon it while nosing through the back storage area in the Archives where I volunteer.

It’s a gorgeous old machine … and yet such an enigmatic one! What was it and what was it used for? Take your best guess!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and “Hidden History of Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our columnists like Laura Bien and other contributors. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

It looks to me like a type of cylinder phonograph recording device; also known as a dictaphone. Someone had to record the things that the early cylinder gramophones played.

Bear beat me to it – I also think it’s some kind of dictation machine.

Welcome back Laura

I think it is an early vacuum cleaner. You know to suck up errant marshmallows.

OK so I am wrong. But I could not figure out how to fit a marshmallow into the right answer.

Bear: Interesting guess. If it’s of any help, this item weighs quite a lot!

ABC: Thank you; it is good to be back. Errant marshmallows underfoot everywhere is no laughing matter, to be sure. The Ypsi Museum has an ancient old “pneumatic cleaner.” One hand pumps the cylinder while the other moves the suction head. It’s billed as “portable,” which in this case is a somewhat fanciful use of that word. Some pictures of it.

TJ: Hmm, another intriguing guess. Aside from a little rust, this item is in very good condition. Does make one wonder how long modern-day devices will be around. Will there ever be an antique iPhone?

Sure there will be antique iDevices but they will be far less interesting to average people, unless you are an electrical engineer. Take the iPod (almost an antique today). 100 years from now it will apprear to be a skipping stone. People seeing it will turn to one another and say, “Wow, people had to carry their music around. Implants are so much easier.” “But hey what were those wires for?” “They stuffed those things in their ears too. Ewwwww!”

A little too easy. Note that it’s not necessarily a Dictaphone, which was the largest company making dictating machines, but there were others.

I used to own a Dictaphone, which I bought for $5 at UM Property Control (now Dispo) around 1962. It came with a box full of blank cylinders and after changing a few tubes it worked fine.

First thought was some sort of dictating machine such as the Parlograph or Ediphone which used cylinders for recording.

Jim: Wow, what a find! One wonder where that gem had been hiding, somewhere on campus. The ReUse Center on S. Industrial is another wonderful place in which to poke around; found an old two-bell wall telephone there once, though sadly without its magneto.

Eleanor: Hmm, seems to be a theme here among these guesses… :)

I don’t know if there will be antique Iphones, but at school I have several Apple IIe’s that are 30 years old and work perfectly. They use 5 1/4 inch floppy disks and have never had any maintenance of any kind.

Dan: Amazing….remember those well. No maintenance, even–one wonders how many more years you can use them. Neato.

Sure enough. It is definitely a dictaphone.