Column: Ann Arbor, a One-Party Town

Editor’s note: Column author Bruce Laidlaw served the city of Ann Arbor as city attorney for 16 years, from 1975-1991. Starting with his service at chief assistant city attorney in 1969, he served the city for a total of 22 years. He defended the city in two elections that were contested in court, both involving the election of Al Wheeler as mayor in the mid-1970s.

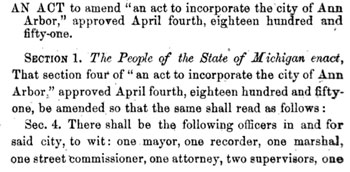

Image links to the Google digital scan of the 1,204-page volume "Acts of the Legislature of the State of Michigan Passed at the Regular Session of 1859." The act in this screenshot amended the act that incorporated the city of Ann Arbor.

As this year’s May 15 filing deadline nears for Ann Arbor’s Aug. 7 partisan primaries, Laidlaw reflects on how it came to be that Ann Arbor’s local elections involve political parties at all.

Ann Arbor was incorporated as a city 161 years ago, by a special act of the Michigan legislature in 1851.

At that time, special acts were required to incorporate cities and business corporations. So Act 101 of 1851, which incorporated Ann Arbor, was the original city charter. Subsequent Ann Arbor city charter amendments were also made by special acts of the Michigan legislature – in 1859, 1861, 1867 and 1889. Ann Arbor was governed under the 1889 special act charter until 1956.

The original Act 101 charter established the offices of a mayor, recorder, marshal, street commissioner, assessor, treasurer, three constables, four aldermen, two school inspectors, two directors of the poor, and four justices of the peace.

Demise of Special Act Cities

The 1908 Michigan Constitution moved control of the organization of cities to the local communities. It virtually outlawed the creation of special act cities. However, existing special act cities, like Ann Arbor, were allowed to continue in that form. The Home Rule Act adopted by the legislature in 1909 provided a procedure for existing or future cities to frame their own charters. But it would be a long struggle before Ann Arbor would adopt its own charter.

Home Rule Ann Arbor charters were proposed and voted down in 1913, 1921, and 1939. A big issue was the “radical” idea of replacing the complex governing system with a city manager. The 1889 Ann Arbor charter spread the administration of local government over a mayor, a common council president, 14 aldermen, a three-person board of public works, a three-person board of fire commissioners, a three-person board of public health, and a three-person board of building inspectors.

The idea of replacing citizen control through the various boards was not popular. Also, the Board of Realtors opposed the 1939 revision because of a fear of high taxes. Nonetheless, the cumbersome system of governance persuaded the electorate to approve the establishment of a charter commission in 1953. The commission’s task was to draft a charter according to the Home Rule Act, that could be put before voters.

The charter commissioners struggled with the concept of a city manager. They announced that they did not want a manager position that had full hiring/firing authority or the usual manager’s budget authority. On the other hand, they said they did not want a mere “errand boy.”

Out of this struggle they came up with the concept of a city administrator. The hiring and firing by the city administrator would have to be approved by the city council. The administrator would not even manage all the departments. The assessor and treasurer would report to the mayor. The planning department would report to the planning commission. (A subsequent amendment made the assessor and treasurer report to the city administrator rather than the mayor.)

Partisan Elections for Home Rule Ann Arbor?

Besides organizational governance, the other key issue for the 1953 Ann Arbor charter commission was partisan elections.

The original Act 101 charter addressed a variety of election issues that were not related to partisanship. For example, the original charter authorized the city to provide part of its financing through a poll tax. Section 31 stated:

The common council is authorized to assess and collect from every white male inhabitant of said city, over the age of twenty-one years, (except paupers, idiots and lunatics,) an annual capitation or poll tax not exceeding seventy-five cents; and they may provide by their by-laws for the collection of the same; Provided, That any person assessed for a poll tax may pay the same by one day’s labor upon the streets, under the direction of the street commissioner, who shall give to each person so assessed, notice of the time and place when and where such labor will be required; and the money raised by such poll tax, or the labor in lieu thereof, shall be expended or performed in the respective wards where the person so taxed shall reside.

The 1851 charter made no mention of political parties. But partisan state, national and local elections were provided by state election laws.

Under the 1889 special act charter and state election laws, nominations for the elected offices had been by a partisan primary election. But the Home Rule Act authorized local elections on either a partisan or non-partisan basis. That was a choice the 1953 Ann Arbor charter commission faced. From persons addressing the 1953 Ann Arbor charter commission, there was little support for non-partisan elections. George Wahr Sallade, who was common council president at the time, submitted a statement saying:

I feel very strongly that partisan elections are an indispensable part of the American democratic process. I have no sympathy with the often repeated argument that there is no Republican or Democratic way of collecting the garbage. After all, that could be pursued further with the statement that there is no Republican or Democratic way to build state highways or direct the state police and therefore the state legislature and the office of governor ought to be filled at a non-partisan election.

[Interestingly, Sallade was elected council president and later a state representative as a Republican. But he later ran for state office as a Democrat.]

Attorney John Dobson told the charter commissioners:

… I urge the retention of the present partisan election system for our local office holders. In Ann Arbor, at least, it seem[s] clear that the citizens have a much greater interest in partisan elections than they do in those which are non-partisan. The records of the persons voting in city government elections as compared with those voting in the city school elections makes this clear. Further, I strongly believe in party responsibility for candidates. By this, I mean that the party offering a candidate for office must assume responsibility for that candidate’s conduct in office. Thus the parties maintains [sic] or should maintain a continuing interest in their candidates performance. They can influence the candidate toward a better performance, and, if this influence is unsuccessful, can eliminate him. I feel that both parties in this community have, generally speaking, met this obligation.

However, a letter from the Ypsilanti manager to the charter commission stated:

I believe whole-heartedly in non-partisan City elections despite the strong argument that partisan politics create interest. I do not believe that a City government’s purpose is to promote interest in politics and parties, as such. I would prefer that government concentrate on service, efficiency and effectiveness and rely on the quality of these to generate and promote interest in local government.

The arguments in favor of partisan elections prevailed. In the report to citizens before the election to approve the charter, the charter commission stated:

The nomination and election of Mayor and Councilmen will continue to be on a partisan basis.

Multi-Party Ann Arbor

Elsie Deeren, who analyzed the 1953 charter commission’s work, offered this explanation for the commission’s recommendation to retain partisan elections:

The support of both political parties had many implications in a town that is predominately Republican, because support by one party only might have made the issue a partisan one rather than a common non-partisan aim for “good government.” Here too it might be said that abandonment of the aim for non-partisan elections was probably very helpful in gaining the support of the Republican party, since, as the controlling party, it would naturally look at any change with a view to the political dominance in town, and non-partisanship would perhaps be regarded as a Democratic device to get more members in office.

To say in 1955 that Ann Arbor was “predominately Republican” was a bit of an understatement. That dominance began with the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. In Ann Arbor, Dwight D. Eisenhower beat Adlai Stevenson by more than two to one. John F. Kennedy did barely better against Richard Nixon. Along the way, several Democrats were elected as mayors. And in 1913 a member of the Progressive Party was elected as an alderman. But Republicans remained firmly in control of the city council until 1969.

Buoyed by a drive to register students, in 1969 law professor Robert Harris was elected mayor along with a Democratic slate of councilmembers. The Democrats gained an eight-to-three majority on the council. Registering students was not an easy task because of a state law that created a presumption that a student’s home town was the place of residency for voting purposes. Students wishing to register in Ann Arbor had to answer questions that would determine whether they still had ties to their home towns. But that changed in 1972 when the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that the law that created the home town presumption was unconstitutional.

In 1971, the 26th amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted. It guarantees the right to vote for citizens over 18 years of age. It overrode the 21 year minimum voting age in the Michigan Constitution and made thousands of additional students eligible to vote in Ann Arbor. Given the propensity of the students to vote Democratic, it looked like the Democrats had a lock on control of the city council. But student activism had moved to the left of the Democratic party.

In 1972, the Human Rights Party (HRP) elected two members to city council seats and pushed a radical agenda. Ann Arbor became a three-party town. In 1973, the HRP nominated a candidate for mayor. That resulted in a split of the progressive vote between the HRP and the Democrats; so Republican James Stephenson won the mayor’s seat, despite getting just 47% of the vote.

To avoid that situation in future elections, the HRP succeeded in pushing a charter amendment for preferential voting – a variant of instant-runoff voting (IRV). Under that system, voters could designate first and second choices on the ballot. If a voter’s first choice did not win, the second choice would be counted to reach the total. In 1975, James Stephenson got the most first place votes, but when the second choices were added, Democrat Albert Wheeler was declared the winner. The election was challenged in court, but the Home Rule Act specifically authorizes preferential voting, and the election of Wheeler was upheld.

The last year the HRP managed to elect an Ann Arbor city councilmember was 1974. In 1976, voters approved a charter amendment repealing preferential voting, and the HRP faded from the scene. In the following 19 years, city council control bounced back and forth between the Democrats and Republicans. That bouncing was ended by a 1992 charter amendment, which changed election dates. [.pdf of current Ann Arbor city charter]

Moving Election Dates

The original 1851 charter called for city elections to be held on the first Monday in April. That definition of election day persisted for 131 years, until an amendment of the current charter in 1992 moved the election to November.

The amendment moved the city primary election from February to August and the city general election from April to November. Proponents of the amendment contended it would result in city council contests being decided at an election with the largest voter turnout. Eventually, however, the result was the opposite. The Republican Party virtually disappeared from Ann Arbor politics. No Republican has been elected to city council since 2003.

Ann Arbor city council contests are now functionally decided among Democrats in the August primary when the lowest voter turnout can be expected. Ann Arbor is once again a one-party town.

Other Cities with Partisan Elections

Ann Arbor is one of only three Michigan cities that still have partisan voting in local elections. The other two are Ypsilanti and Ionia. [Ypsilanti convened a charter commission last year that submitted to the state attorney general a draft charter that would change Ypsilanti's local elections to be non-partisan. But up to now the attorney general's office has not completed its review of the new language.]

In 1985, a Chamber of Commerce-based group held a petition drive for a charter amendment that would have made the Ann Arbor local elections non-partisan. It appeared that enough signatures had been obtained to put the matter on the ballot. However, one of the circulators filled out the petitions improperly. That flaw proved fatal for getting the matter on the ballot.

But the 2011 Ann Arbor city council elections revealed a small chink in the partisan armor that the charter commissioners drafted for the 1956 charter, and that was ratified by voters. The charter makes it possible only for potential nominees of a political party to participate in the August primary election. However, language that was probably inadvertent allows a person to become a nominee in the November election without a party designation.

In 2011, Jane Lumm – who had served on council as a Republican from 1993-98 – chose that approach in the Ward 2 city council election, and proved that city voters are willing to vote for a candidate who does not have a D or an R printed on the ballot next to their name.

The Ann Arbor city council now consists of 10 Democrats and one independent.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our publication of local writers like Bruce Laidlaw. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

It’s spelled Sallade not Salade.

It’s a good thing we can now collect taxes from lunatics and idiots. Surprisingly, that did not take a charter amendment.

Re: spelling of Sallade; thanks.

When did the city redistrict council wards so that there was no longer a “student ward”?

1973 elections generated posters like this one: [link]

Nothing like that now.

Re#4: The City Council actively redistricted in 1981, after the census. (The City redistricts every 10 years.) The Republican majority on Council drew the ward boundaries to create (in my view) two solid Republican wards (2nd and 4th); 1 solid Democratic ward (1st) and two swing wards that were expected to swing R more often than D (3rd and 5th).

The war in Vietnam was over by 1975; Nixon was out of the White House; the $5 Marijuana possession charter amendment was passed. A lot of the issues that had energized a young electorate were non-issues; those folks graduated and moved on toward the next phase of their lives. By 1983, Democrats were mourning the decrease in student activism and student turnout.

I don’t remember clearly the 1971 ward boundaries, but I know that in 1981 the revision moved the boundaries counter-clockwise, with each boundary moving left by several streets (without moving, I moved from the 4th to the 5th Ward, for instance). The City also moved left, and by the end of that decade, Republicans tended to win only the 2nd and 4th Wards.

The elections were changed to November in 1992, as Mr. Laidlaw states. The rest is history.

I worked for Bruce Laidlaw as an attorney for about 15 years–he was outstanding. A brilliant lawyer, non-political, helpful but never micro-managing, and always ethical. A huge void in corporate history was created by his leaving. You can see this from his knowledge of the history of the City