In the Archives: Diary of a Farm Girl

Soaring over Washtenaw County’s Superior Township on Google Maps gives the illusion of eagle-eyed omniscience. The plat map book lying open next to the computer shows that the meticulously-drawn maps of 19th-century farms correspond in good measure to the present-day brown and green patches on the screen.

This group of 19th-century schoolchildren from Morgan School may give a general idea of Mamie Vought’s Fowler School class size.

Look – there are the outlines of the old Philip Vought farm on Ridge Road in eastern Superior Township. A fleeting sense of connection dissolves with the realization that the outline is only that – the chance to understand the lives of onetime residents is gone.

Would I have enjoyed growing up on the Vought farm?

What did a typical day involve?

How foreign and slow would a childhood be – measured not in miles per gallon but in wagon rides and footsteps?

Thirteen-year-old Mamie Vought left us her 1886 diary to let us know.

More a logbook than a reflective memoir, the diary’s entries chart Mamie’s parents’ routines, events on the farm, and the ceaseless round of visiting between Mamie and her friends, neighbors, and relatives. It becomes apparent, however, that Mamie’s short, telegraphic entries are also only outlines of her experience as a farm girl.

Oblique offhand clues in a year’s worth of entries and additional research in historical materials related to the farm help develop this blank outline into a hazy picture of a two-story farmhouse and barnyard in which appears a small ghostly figure in skirts, her features almost discernible.

Wednesday, June 30, 1886: Ma baked bread and pudding for dinner. I went over to see Myra a few minutes this morning. We picked cherries. Myra and Myrtie was here in the after noon we had fun a lot of it too.

Mamie’s father and mother farmed 160 acres on Ridge Road near Geddes Road. Philip and Mary’s farm resembled those of their 19th-century county neighbors in that they cultivated a range of crops and livestock, akin to the largely-vanished red-barn farms still romanticized in modern-day children’s books.

Philip had 137 of his 160 acres under cultivation. He grew mostly Indian corn as winter silage for his cows. He also grew 9 acres of oats, 4 of wheat, and had 3 acres of apple trees. Three acres of his property were pastureland for his cows and horses. Twenty acres were forest. Mamie – with her younger sister and only sibling, Abbie – explored the forest and gathered flowers there in the summer. In fall and winter, Philip and his hired farmhand George felled trees, dragged logs, and split wood for the farmhouse kitchen’s wood stove.

In 1880, Philip harvested 40 cords of wood and sold some of it for $60 [the equivalent of about $1,300 today]. He also raised bees and harvested 120 pounds of honey. A number of hogs milled around in his hog pen. In all, he earned $2,600 in farm income that year [$60,000]; his property was valued somewhat higher than those of his neighbors, at $13,000 [$290,000].

The two-story farmhouse was roomy and comfortable. Carpet lined the floor next to walls that Mary had neatly whitewashed. The home had bedrooms, a dressing room, a dining room, a front sitting room with a new sofa, and a kitchen. Mamie had her own room with a cozy handmade quilt on her bed, her school materials, her sewing supplies, her doll, her fish hooks, her colorful hair ribbons, her collection of 447 buttons (some sent through the mail from distant friends), and her tiny diary.

Though no picture exists in the Ypsilanti Archives of Fowler School, this look at Delhi School may give some idea of the appearance of Mamie’s school. The flag appears to be the 45-star flag used from 1896-1908.

In the farmyard, Mary was in charge of the garden, where she grew cucumbers, green beans, cabbage, radishes, potatoes, peas, and other crops. She also had jurisdiction over the turkeys and chickens, periodically slaughtering batches of birds to take to Ypsilanti and sell to a meat merchant for resale to town residents – no USDA approval required.

This was the hyper-local food system in place in 19th-century Washtenaw County. Philip took his oats and wheat to town for sale, and Mary did the same with her birds. On February 10 of 1886, Mary and 13-year-old Mamie killed, plucked, and gutted 44 chickens for sale; they fetched $15.25 [$340] in town, roughly $8 apiece. A similar lot of turkeys earned $46.20 [$1,030].

Mamie helped her mother with other chores. Every Monday, Mary did the family laundry, and every Tuesday, ironed the clothes with solid cast iron hand-irons heated on the kitchen stove. Mamie often helped with the ironing. On one occasion, with relatives in the house and an extra-large load of ironing, Mamie ran to a neighbor’s house to borrow some extra flatirons.

Mamie walked the half-mile to the onetime one-room Fowler schoolhouse that stood just south of Geddes near Ridge Road. She was a good student, and in more than one spelling bee “spelled down the school.” It’s not known to the author whether she attended high school, but even by 1900, fewer than 6 percent of all grammar school graduates across the nation also graduated from a high school.

After school let out, or on one of the many days when she stayed home from school for no stated reason, Mamie worked on a patchwork “crazy work” needlework project, made clothes for her doll, helped hoe the garden, baked cookies, wrote letters, went fishing, or played in the playhouse her father had made (Abbie had her own). Most of Mamie’s free time was spent visiting neighbors and playing with friends.

Tuesday, March 23: Ma ironed and baked bread and biscuit for dinner. Mr Westfall [a neighbor] was here all day. Abbie and I went over to Christie’s and Myra came home with us. I pulled out Abbie’s first tooth.

Wednesday, March 24: I went over to Christie’s but could not go in because Clem had the mumps. George cut wood all day. Abbie and I helped him cord it. Ma worked on her dress.

Thursday, March 25: Christie was over this morning a few minutes. I mopped my first time today. Ma churned. George made the rail cribs to day. Abbie and I found a nest with eleven rats in it. Ma set 2 hens in the hog pen [on nests with fertile eggs to brood and hatch].

Mamie’s diary gives some idea of the diet of a 19th-century Washtenaw farm family. She takes note of the occasional chicken supper as though it were a special occasion. Other suppers she mentioned featured bean stew, soup, peas, string beans, hash, and a onetime meal of roast beef, the only mention of beef that year.

Sunday, January 3: Ma went over to see old Mrs. Gill in the fore noon. Ma and Abbie and I went over to Christie’s, in the after noon. We had a roast of beef for dinner all ate lots and it has been a rainy day all day long.

Mamie’s mother baked bread once or twice a week and churned butter about once a week, producing about 200 pounds of butter per year. Mary also regularly baked pies and cake. She made shortcake, fruitcake, and fruit pudding. Fruit that the family consumed included strawberries, cherries, gooseberries, blackberries from the woodlot, and apples. Mamie and her friends gathered wintergreen from a nearby marsh. The family obtained some groceries from town such as sugar and tea.

The diary also gives an idea of Mamie’s wardrobe. In addition to the clothes she already had in 1886, that year she acquired several items sewn by her mother: two skirts, a blouse, and four dresses that included a red dress, a plaid dress, and a Mother Hubbard, a sort of cover-all sack dress. That most of the items were finished in just two or three days amidst all of the other regular chores suggests that her mother owned a sewing machine. Some of Mamie’s clothes were store-bought, including a fancy collar, a hat, a bonnet, rubbers, a jacket, slippers, and hair ribbons.

Friday, November 12: Ma, Abbie, and I went to town this morning left pa to bake the bread. I got me a bonnet and Ma got her one. After we got home I went to Myra’s + she came home with me.

Tuesday, November 16: Abbie and I went to school. Ma ironed all this A.M. + worked on my red dress this P.M. It snowed to day.

The family went to town regularly but other entertainments were few. In early summer Mamie and her family visited the traveling circus in Ypsilanti. In late August she took a week-long trip with her family to Detroit to visit relatives, a vacation that included boat rides to Belle Isle and on the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair. The trip featured the one occasion that year that the family ate at a restaurant, at a hotel. Mamie also visited an Ypsilanti fair in late September. Otherwise Mamie entertained herself in a world without movies, television, or even radio, and much less electricity – as rural electrification would not arrive for decades.

At age 20, Mamie married Edward Pierce Rogers on December 28, 1893. Though the time of year seems unusual for a wedding, no fewer than four other wedding announcements appear in the same issue of the weekly Ypsilanti Commercial. Even the Ann Arbor Argus took note with this jocular tidbit from January 5, 1894:

Edward P. Rogers and Miss Mamie E. Vought, of Ypsilanti, are now conducting business under the firm name of Edward P. Rogers & Co. A large number of relatives and friends witnessed the ceremony. Many choice and useful presents.

The couple wed at Cherry Hill, a town at the intersection of Cherry Hill and Ridge Roads just outside of the Washtenaw county line. The couple moved to Ypsilanti, taking rooms at 119 Washington. Edward worked as a butcher, with a shop on Huron Street and later on Michigan Avenue. Mamie had two children, Myrtelle and Phillip. Mamie’s mother had lost two infants to illness before Mamie and Abbie were born, but Mamie never experienced that tragedy.

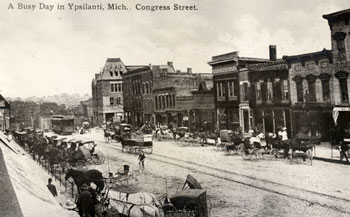

Michigan Avenue as it appeared when Mamie’s husband Ed ran a butcher shop there. His shop would have been towards the far side of the block pictured.

In 1911 the family moved to Detroit. By 1920, Ed worked as a salesman and Mamie operated part of their home as a boarding house, providing rooms and meals for 2 tenants. Myrtelle worked as a high school teacher and Philip as an insurance agent. Both lived at home.

In just a few decades Mamie’s world had changed completely. Her house was electrified and had running water. She bought all of her food. She heard the new technology of radio crackle to life, filling the house with music. Outside, the streetcar clanged past amid crowds of motorcars. By 1930, Ed worked as an assistant manager of a wholesale meat firm and Mamie ran a small restaurant. Their home had three boarders coming by for meals and two lodgers.

When Mamie died in 1944, shortly after her and Ed’s 50th wedding anniversary, the Ypsilanti papers remembered her with an obituary that mentioned the Superior Township farm. There, on quiet nights lit by kerosene lamps, Mamie had once dipped her nib pen into her violet ink and sent her words over a century into the future.

Mystery Artifact

No fewer than three people correctly guessed last column’s Mystery Artifact: an antique stapler. Chuck Welch, Jim Rees, and Johnboy were correct.

Johnboy commented, “I have the exact same model sitting right here on my desk. Labeled ‘Swingline Speed Stapler 3’ Slide back the side tabs and the head opens up and swings back to load.” Good job, guys!

This time we’re veering more towards the strange with this odd toothy item. Because it’s so unusual, here’s a hint: the brand logo stamped on the item reads “109 A POPELL Product Made in USA.” Good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Hidden History of Ypsilanti” and “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Look for her article on Coldwater School, a short version of which first appeared here, in the July/August issue of Michigan History Magazine. ypsidixit@gmail.com

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to keep our pants from falling down. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

I imagine winter weddings might have been popular in rural Michigan because the frozen ground and snow cover made travel over dirt roads a bit easier. Lots of logging work was done in the winter for the same reason. That and the reduced need for labor on the farms in winter.

I recently discovered that Wikipedia has pages for each year, listing events that year. It’s fun to see what else was happening in Mamie Vought’s world in 1886. [link]

Here are some interesting dates:

January 29 – Karl Benz patents the first successful gasoline-driven automobile, the Benz Patent Motorwagen (built in 1885).

February 14 – The first train load of oranges leaves Los Angeles via the transcontinental railroad.

May 1 – A general strike begins in the United States, which escalates into the Haymarket Riot and eventually wins the eight-hour workday in the U.S.

May 8 – Pharmacist Dr. John Stith Pemberton invents a carbonated beverage that would be named Coca-Cola.

June 2 – U.S. President Grover Cleveland marries Frances Folsom in the White House, becoming the only president to wed in the executive mansion. She is 27 years his junior.

September 4 – After almost 30 years of fighting, Apache leader Geronimo surrenders with his last band of warriors to General Nelson Miles at Skeleton Canyon in Arizona.

October 28 – In New York Harbor, U.S. President Grover Cleveland dedicates the Statue of Liberty.

Mr. Hammond: What an interesting comment. Yes, logging in northern MI was done in the winter. Sometimes loggers would even put water on the logging roads to make them slippery ice for greater ease of transport for the huge loads of logs. The issue of logging-camp prostitution, which extended even to permanent prostitution camps, is an interesting and largely unexplored aspect of MI history but that’s a story for another day.

Ran a little off the rails there. To get back to your comment, thank you for providing bits of historical context. The oranges note reminds me of reading of Laura Ingalls getting an orange (!) in her Christmas stocking. This era, the turn-of-the-century Progressive era, is the one which fascinates me the most. Many parallels to our own era: drastic technological change, labor unrest, efforts to combat corporate monopolies, and champagne-lubricated lifestyles of the fabulously rich of the Gilded Age.

Thank you for your informative comment!

…Would also be interesting to do a portrait of one of the so-called “shanty girls” who worked as cooks in the northern logging camps. One wonders what circumstances might lead a young woman to leave home and work in such a rough-and-tumble environment. It’d call for a good deal of gumption and grit, and she would have been perceived, disapprovingly, as an outlier in her day–the outliers are usually the most interesting people to me personally.

My mother, born in 1915 in MA, had one of these Mystery Objects. I think that it had belonged to her mother. We used it as kitchen tongs. I don’t recall any brand logo stamped on it.

“Mamie’s father and mother farmed 160 acres on Ridge Road near Geddes Road. Philip and Mary’s farm resembled those of their 19th-century county neighbors in that they cultivated a range of crops and livestock, akin to the largely-vanished red-barn farms still romanticized in modern-day children’s books.”

Ms. Bien

Your account was very enjoyable to read however I would like to make a small point about what Philip’s and Mary’s farm may have resembled. To me it is interesting to note that in 1886 most of the existing barns in Michigan were gable barns; they just had two roof slopes. This is about the time period where the farmers almanac was just writing about the virtues of gambrel roofs due to the 1860’s and 1870’s advances in hay processing technology (hay forks and steam-driven hay loaders).

As you may already know, farmers sometime need more than a little push to change their ways. So while the new technology was introduced it took some time, and proof, to be accepted and only then would farmers alter their farms to accommodate these new techniques.

In Washtenaw County I know one barn built after the Civil War that was built as a gable. I also know of another gable barn (circa 1850) that was moved to an 1890’s foundation (it is dated) where the roof was lifted, probably during the move, but still left as a gable. This tells me that the community may not have embraced gambrels yet, or this was one stubborn farmer. (Of course I know of many 1800’s barns here that were converted to gambrels.)

Why is this interesting (at least to me)? Because most barns, romanticized in modern-day children’s books, are gambrel barns (having four roof slopes). And in Michigan, most, older gambrel barns were converted by having their roofs re-built. These conversions would have occurred starting in the late 1880’s, but starting slowly, and then carrying through to the early 1900’s. In Michigan if you find a gambrel barn that is not converted it is fairly new; it is usually a 20th century barn.

I gleaned from the article that in 1886 this was an established farm from the description of the farm, and the house, and the fact that Philip and Mary made $13,000 six years earlier. My guess then is that the latest this farm could have been established is right after the Civil War, but it could have been even older as armies march on their stomachs, so farms were very important. All barns in Michigan before and right after the Civil War were gable barns.

So back to Mamie, I think when she looked out of her window, after writing an entry in her diary, she gazed out over a big red gable barn; made of hand-hewn timbers and held together with mortise and tenon joinery. She saw an imposing building; the most important one there. The barn was the heart of the farm.

The comment on barn architecture is interesting to me. I personally love old barns, especially those with gambrels. They are part of the inner picture many of us carry of the American farm landscape. I’m always glad to see one preserved even though they are not current technology.

This book has a good deal of information about Michigan barn buildings and farm families. [link]

From his comment, it’s clear that Bultman knows a bit about barns. For readers who might wonder why, he’s an architect who has undertaken more than one barn restoration project. Some readers might remember an article he wrote for The Chronicle about two years ago: “A Broadside for Barn Preservation”

I would also add that there’s an super-fun looking event involving barn preservation, coming up on Sept. 15 from 1-5 p.m. at the Pittsfield branch of the Ann Arbor District Library:

Details here.

Mr. Bultman: Thank you for your extremely informative and interesting comment. I appreciate the time you took to detail this information about barn roof construction. I always appreciate learning useful information from people who know far more about a given subject than me, and I read your comment with great interest. Thank you–I learned something. For what it’s worth, the Vought farm first appears on the 1864 plat maps; it’s not labeled on the 1856 maps (I don’t have any intervening plat maps on hand).

I’ve seen a smallish gable barn on Stony Creek Road south of AA, built on four little columns of stones at each corner. It looks quite old. I appreciate learning that gable barns were the onetime standard and that gambrel barns were a later innovation–this sort of information is key to drawing an accurate picture of the past, and I appreciate your kind help in doing so.

Ms. Estabrook: That is interesting! No one else I’ve shown this object to has ever seen it before. To hear from someone who actually used this object is fun. Despite its age, this object still works perfectly.

Ms. Armentrout: Thank you for the recommendation for “Michigan Family Farms and Farm Buildings.” Your recommendation and Mr. Bultman’s comment have made me interested in learning more about farm architecture; I’ll see what I can find in the university and public libraries near my home. Thanks to you both.

While I’d like to take credit for guessing the previous Mystery Artifact, I think the credit should go to TJ, who was the first to guess it was a stapler. I was simply agreeing with him. Chuck identified the manufacturer, and Johnboy the model.

I think this month’s item is for serving some food, maybe pasta or salad.

Jim: Duly noted and it is fair of you to say so. It’s a heck of a stapler, to be sure. And a beautiful object that I just enjoy having on my desk. Thank you for your comment. :)

.

Ms. Bien

I am pleased to contribute to your wonderful piece. From your map research, I stand by my guess that this barn was a gable barn at the time of the dairy entries. The farm is between 11 and 16 years old when Mamie was born (I guessed the earliest year for the farm to be 1857 assuming that the establishment of the farm did not happen a moment after the 1856 map was published.) Within this time frame one can imagine the establishment of the farm to profitability and the loss of the two children you noted. From my perspective I would not expect a gambrel barn to be built in Michigan between 1857 and 1864. Only if the barn was brand new when Mamie was writing would I expect it to be a grambrel; and then it still may not have been. With only one year of dairy entries (which is all I think you have) it’s hard to flesh out the history, but its fun to try.

David

I really appreciate your putting in a plug for the Pittsfield Library’s barn raising here. I am looking forward to bringing this scaled model of a real barn to AA and to spending the afternoon talking about and building a barn. Working with this barn at different venues around the state has been incredibly rewarding and fun for many kids; and adults as well.

After we brought the barn to the Leland School System for a very aggressive program (all of the 3rd, 4th,7th and 8th graders in the school; 150 students in two days!) I wrote the following for the MBPN’s newsletter. “The barn was raised in a relatively short time frame transforming the 100 or so parts into one building; eliciting exclamations and applause each time. Shy kids were grinning ear to ear as the barn took shape. It was all we could do at times to keep a safe pace as seeing the first bent made them anxious to see the second, and then the third; it was a real building and they were building it themselves. The enthusiasm was absolutely contagious and spread from the students to the teachers; everyone lent a hand. And seeing everyone working side-by-side, helping each other regardless of age or position, was nothing short of magical.”

I think it is great opportunity to be a part of a real barn raising; and it is real. Even scaled-down this barn has to be erected just like a real barn and it takes many hands. I have now erected it many times and each time I still have a sense of accomplishment. It is also a wonderful opportunity for children, and adults, to spend some quality time considering how people have been building wooden buildings for thousands of years. Oh and we get to talk about barns and farming, a well as history and community, and so much more.

It is my desire to overwhelm the library with participants so I hope all of you will consider attending. Also all of you should know that if you have an event where this barn could prove to be valuable the MBPN would be interested to try to work with you. This barn has been to barn conventions, agricultural expositions, state fairs, schools, career expositions, heritage festivals all over the state and beyond and has been well received. If you would like more information feel free to contact me at cbultman@flash.net. You can also see photos of the barn at the MBPN’s website [link].

p.s.

David, I purposefully squandered the previous comment slot as I did not wish to have that number next to my comment. I hope you can understand.

Laura,

My daughter & I have put our heads together and we believe the mystery object to be for picking up ice chips.

Irene

For those who enjoy tasty “corn on the cob,” a device such as this would be handy for grabbing the ears of corn out of a pot of boiling water. It would be even handier/safer, if the handle were extended a bit.