In the Archives: Lightning Rod for Swindles

Editor’s note: Laura Bien’s most recent “In the Archives” column highlighted a 19th century scam involving oats. That column briefly mentioned a lightning rod scam. In this month’s column Bien provides a bit more background on lightning rod swindles.

Scams and swindles proliferated in the late 19th century, despite a sometimes idealized modern-day view of the period. “Work at home” offers targeted housewives in an era with very few opportunities for women to gain respectable work outside of the home. The candidate had to purchase a sample embroidery kit or small artwork, complete it, and return it to the company. Invariably, the finished work was never acceptable – because the companies made their money not in farming out work to home-based workers, but in selling samples.

Patent medicines were rife. Food adulteration was common. Fake doctors took trains from town to town, offering miraculous cures. Promissory-note shenanigans took place.

One little-known yet strange swindle, which affected Washtenaw County farmers, the state as a whole, and elsewhere, involved no more than a simple metal stick – a lightning rod.

Swindling Fraternity

“Next to the substitution of saw-dust packages for counterfeit money, and the sale of brass jewelry, the business of putting up lightning rods is a favorite field for the operations of the swindling fraternity,” wrote John Phin in 1879. Phin was a onetime faculty member of New York’s People’s College and the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to publishing a Shakespeare encyclopedia, several works on microscopy, a treatise on “Open Air Grape Culture,” and a primer on the “Preparation and Use of Cements and Glue,” Phin also published “Plain Directions for the Construction and Erection of Lightning Rods,” from which the above quote is taken. At an 1871 meeting of the American Institute of the City of New York for the Encouragement of Science and Invention, he was regarded as the reigning expert on the subject.

From beyond the grave, Ann Arbor’s Dr. Alvan Chase warned readers of the dangers of the lightning-rod men.

The swindling fraternity to which Phin referred consisted of itinerant lightning-rod men plying backroads in a wagon. When they visited farms they used one of at least three methods of trickery.

Ann Arbor’s own Dr. Alvan Chase, author of the popular 1896 book “Dr. Chase’s Recipes, or, Information for Everybody” described one such tactic in his posthumous 1894 book “Dr. Chase’s Home Advisor and Everyday Reference Book.” “The scheme is to sell the lightning rods, and to take pay, usually in the form of a swindling note or contract, which is placed in the hands of an innocent third party, and can be collected.” In other words, after securing a promissory note from a farmer, the swindlers could cash it at a bank. The farmer then had to contend with the authority of the bank – perhaps the one that held his mortgage – as the bank attempted to redeem the note for cash money.

Another scheme involved altering the contract presented to the farmer. After taking an order from a farmer and filling out a contract, the swindler would alter it. “After the contract is signed, the sharper inserts a 5 before the 7, making the amount per foot 57 instead of 7 cents,” noted Edward Roe in his 1904 book “Safe Methods, or, How to Do Business.” He continued, “And there being nothing said in the contract as to the number of points, vanes, etc. to be used, the lightning-rod man throws them in ‘good and plenty,’ so that instead of the business costing [the farmer] about $28 as he expected, he finds that the bill runs up to $185 …”

“Two men are working a new swindle among the farmers,” reported the Sept. 21, 1888 Marshall Statesman. “They claim to represent the National Tube lightning rod company and [have been] sent out by an insurance company to inspect lightning rods.” After the rods were “tested,” said the paper, invariably they were found defective. The men offered to replace them. “It’s the old story after that,” continued the paper. “[T]he farmer who signs obligates himself by a sleight-of-hand trick of the agents to pay two or three times the value of the rod.”

Fire Insurance

Lightning rods served as a lever for swindles for several reasons. One was the lack of reliable rural fire service and telephony. Washtenaw County towns had municipal fire services. Ann Arbor organized a primitive one in 1836 when the city was a village with only two small wards, according to Chapman’s 1881 “History of Washtenaw County.” Ypsilanti organized a fire department in 1873. Dexter followed suit in 1877, Manchester in 1883, and Chelsea in 1889. The farmer in a distant township, however, was largely on his own.

Some farmers forewent the expense of insurance, though many plans were available from a variety of states. The 1890 Polk’s Ann Arbor city directory lists 52 insurance companies in all: one exclusively for plate glass, three for life insurance, three for accidents, and 45 for fire insurance. Many local policies were sold by James Bach from his office at 16 E. Huron Street, among other agents.

In contrast to these stockholder-based insurance companies, Washtenaw farmers organized at least four local mutual farmers’ insurance cooperatives. The Ann Arbor-based German Farmers’ Mutual organized in 1859, as did the Ann Arbor-based Washtenaw Mutual. The Manchester-based Southern Washtenaw Farmers’ Mutual formed in 1872, and the Dexter-based Northwestern Washtenaw Farmers’ Mutual began in 1898. Regardless of this panoply of choices, some barns still burned to the ground uninsured.

In 1905 the secretary of Washtenaw Mutual gave a summary of his company’s recent claims, as reported in the September 7, 1905 issue of the Western Underwriter. “The largest number of losses, thirteen, occurred in November, seven by fire and six by lightning. July was second with ten losses, all lightning . . . [f]or some reason not fully understood, the number of lightning losses is on the increase.”

Lightning was a leading cause of fires in the era. Turn-of-the-century annual reports from the Michigan Insurance Bureau categorized seven causes of fires: lightning, steam threshers, incendiary [arson], field or forest fires, defective chimneys or stove pipes, unknown, and miscellaneous. For both 1886 and 1903, lightning was the second-largest cause of all fire claims submitted to Washtenaw Mutual, exceeded only by faulty stove pipes. In 1886 Washtenaw Mutual paid out $1,712 for lightning claims, the equivalent of $43,000 today.

One additional possible reason for farmers’ vulnerability to fraud was a general lack of information. Without reliable access to news, including communication technologies or the local turn-of-the-century institution of rural delivery mail routes (which also delivered newspapers, many of which were printing warnings against the swindle), farmers may have been at a disadvantage.

Some farmers had little tolerance for the marauding lightning-rod men, as depicted here from the 1907 book “Swindling Exposed, from the Diary of William B. Moreau, King of Fakirs.”

Regardless, some farmers rebelled against the traveling agents. “A farmer in St. Clair County settled a note given to a lightning rod swindler,” said the February 6, 1878 Owosso American, “by grabbing the note when it was presented for payment and kicking the swindler off his premises.” The July 9, 1906 Marshall Daily Chronicle reported, “[One] farmer was given a second ‘contract,’ to which he affixed his signature. The swindlers were unable to cash the note in the vicinity, and one farmer got rid of the slick chaps by threatening to use a shotgun.”

The widespread fraud took its toll. “According to the Bureau of Standards it has been estimated that not more than fifteen or twenty per cent of the buildings in the United States which are liable to damage by lightning are protected in any manner against it,” reported the January, 1921 issue of the National Fire Protection Association Quarterly. “The lack of protection is charged largely to swindling lightning-rod agents of thirty or forty years ago, who prospered greatly at the expense of a credulous public.”

Over time the stigma faded. The swindlers drifted off – only to resurface in 2011 in Kansas, last May in Pennsylvania and last November in rural Wisconsin. Here’s hoping the local sheriff “conducted” the swindlers out of town.

Mystery Artifact

Jim Rees correctly guessed last column’s mystery artifact.

It is a “Dice Box” patented by Ann Arbor’s Eugene Gregory in 1894. Talk about a great guess!

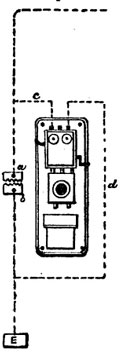

See if you can suss out this column’s mysterious 1892 diagram. What does this depict? Take your best guess!

Contact Laura at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to keep us from falling prey to lightning rod scams. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

I suppose swindling is in the eye of the beholder, Dr. Chase having recommended various liniments, “consumptive syrups,” and “cholera tinctures” for the local populace. Found his book on the MSU library site: [link].

The object looks like some sort of doorbell.

Dr. Chase’s book seems at first glance like it might be pretty hilarious. From a recipe for popcorn balls: “… then with the hands press the corn into balls, as the boys do snow balls, being quick, lest it sets before you get through.”

After I read “Something Wicked This Way Comes”, I became obsessed with our house having a lightning rod. I think my dad had to talk me down from the one :)

Is that a diagram for a telephone? (Remember when phones were a thing…in a room and they just made phone calls?)

Joan, there are indeed some interesting recipes in his recipe book, aren’t there? I so enjoy reading his recipe book, though, because his personality is so evident and because I admire his chutzpah in blithely assuming that he was qualified to hand down advice on, well, everything. It is an endearing and very amusing book, and also sheds light on issues of his time; historically valuable in that way.

Dave: This is a man who instructs you on everything from “management of childbirth,” “gunsmithing,” “food for the sick,” “abdominal lifting,” “cements, various,” “gloves, to clean,” “horses, to teach tricks,” and “magnetic ointment” to……….how to make a popcorn ball.

And, it’s readable on Google Books! [link]

TeacherPatti: I do remember those days; my dad still has such a phone, corded and all. My own landline is also a corded phone (no cell phone).

I think it’s a diagram for how to keep lightening from blowing up your phone, or at least not burning down your house when it does. The pair of close-spaced toothy things on the left is the gap the lightening is supposed to jump on the way to (E)arth.

Interesting guess Fritz; we shall see. :)

To be fair, I think Cosmonican deserves credit for the dice machine.

The object in the diagram is obviously a telephone. A very old one, with a “non-metallic” or “earth return” connection. These were very susceptible to lightning, and Fritz is right, the toothy thing is what we would today call a “surge suppressor.”

Non-metallic circuits were no longer installed after WWI, but some continued in use until the 1940s. Metallic circuits (what we use today for land lines) still have surge suppressors. From the 1920s to the 1980s these were a black bakelite block with screw terminals mounted in the basement, and many of us still have them even if they are no longer connected. The had a both a spark gap and a carbon block. Suppressors today are located inside the demarc, the gray plastic box on the outside of your house.

Looks like a schematic for a crank telephone.

Irene Hieber