Waste as Resource: Ann Arbor’s 5-Year Plan

Initially scheduled for consideration earlier this summer, a new five-year solid waste plan may now see action by the Ann Arbor city council sometime this fall, according to solid waste manager Tom McMurtrie.

The Recycle Ann Arbor booth at the annual Mayor’s Green Fair held this year on June 14. The relative size of the containers reflects the goals for the amount of compostables, recyclables and material to be landfilled. (Photos by the writer.)

The council will be asked to adopt a draft plan that includes a number of initiatives, including goals for increased recycling/diversion rates – generally and for apartment buildings in particular. A pilot program would add all plate scrapings to the materials that can be placed in the brown carts used to collect compostable matter.

And if that pilot program is successful, the plan calls for the possibility of reducing the frequency of curbside pickup – from the current weekly regime to a less frequent schedule. Also included in the draft plan is a proposal to relocate and upgrade the drop-off station at Platt and Ellsworth. The implementation of a fee for single-use bags at retail outlets is also part of the plan.

City staff had originally intended to place the adoption of the solid waste plan on the council’s legislative agenda much earlier than this fall. The work on updating the plan had already begun over 18 months ago, in January 2012. And a bit more than a year later, on Feb. 28, 2013, the city’s environmental commission had voted to recommend that the city council adopt the plan.

This article begins with a look at one reason for the delay – which was not related directly to the plan itself. That’s followed by a brief look at the solid waste fund, which pays for the collection of trash, recyclable materials and yard waste.

Revenue to the fund is then considered in terms of the idea that solid waste is a resource, something that’s reflected in the title of the proposed update to the city’s solid waste plan: “Waste Less: City of Ann Arbor Solid Waste Resource Plan.” In particular, this report looks at a recent $2.50/ton negative impact the fund recently needed to absorb – due to the cancellation of a contract with the company that was purchasing the recycled glass product from Ann Arbor’s materials recovery facility (MRF).

Even though prospects for replacing the contract with a different buyer appear good, the cancellation of that contract highlights a significant consideration: Waste collection services in a local municipality depend in part on revenues that are subject to market forces that can lie beyond the direct control of that municipality.

So one section below takes a look at prospects for developing more influence on the markets – at the level of state economic development efforts. That includes the unintended negative impact that an expansion to the state of Michigan’s bottle bill could have on revenues to local MRFs. One argument for the bottle bill’s expansion is that it will reduce litter from newer types of containers. That’s also one argument for the possible local plastic bag fee recommended in the draft solid waste plan.

Beyond financial viability, success is also defined in the five-year plan partly as increased “diversion rates.” So this report also looks at that statistic and what it actually means.

Delay in Presentation to the City Council

On Feb. 28, 2013 – after more than a year of work by an advisory committee, which divided further into subcommittees – the city’s environmental commission voted to recommend the plan’s adoption by the city council.

The original timeframe for the council’s consideration of the updated solid waste plan included a scheduled May 13 work session on the topic – with the intent that the adoption of the plan would come to the council vote on June 17. However, the council’s focus this spring was occupied with controversial downtown planning and development issues, which led to a meeting on April 15 that lasted until 3 a.m. And at that meeting, the council postponed a significant number of items until its May 6 meeting.

The extra-long May 6 agenda led the council to recess that meeting before it handled all the agenda items, and resume it on May 13. That made the May 13 work session on the solid waste plan a casualty of the council’s focus on downtown development issues. And that led to the omission of the solid waste plan from the council’s published agenda on June 17.

About the Solid Waste Fund

Despite the cancellation of the May 13 council work session on the solid waste plan, solid waste featured prominently in the council’s May 20 budget deliberations a week later. That came in the context of a proposal brought forward by Jane Lumm (Ward 2) to restore a loose leaf collection program, which the city had previously discontinued. The proposal failed on a 5-6 vote.

At the May 20 meeting, city solid waste manager Tom McMurtrie was asked to outline budget implications for a loose leaf collection system. A major risk to the solid waste fund identified by McMurtrie on that occasion was the need to replace and relocate the drop-off station, as it slowly sinks in its current location atop a former landfill. That’s one of the recommended actions in the draft five-year solid waste plan.

Together with A mandated accounting change that has to be implemented in FY 2015 (GASB 68) [$4.5 million], together with the replacement of the drop-off station [$4.9 million], could require as much as $9.4 million. That’s more than the current unrestricted (available) balance in the solid waste fund, which comes to $8.6 million. [.pdf of financial breakdown of solid waste fund provided to city council in spring 2013]

Solid Waste Fund: Tax Levy

At the May 20 city council meeting, Lumm argued that given its $11 million revenue stream from the solid waste tax, the solid waste fund surely could absorb the costs of offering the loose leaf collection service: a one-time cost of $395,000 (to purchase street sweepers) and an ongoing annual cost of $285,000. Historically, residents had been invited to sweep their leaves into the streets based on a set schedule in the fall. The city staff would use modified street sweepers to push the leaves into large piles, and front-end loaders were used to fill dump trucks. That service was last offered in 2009.

The $11.4 million that the solid waste fund is expected to receive in FY 2014 tax revenues is the result of a millage levied at a rate of 2.467 mills on real property. A mill is $1 for every $1,000 of taxable value. By way of comparison, Ann Arbor property owners pay a bit more than 2 mills to support public transportation, about 2 mills for street repair, a bit more than 1 mill for parks maintenance and capital repair, and almost 0.5 mill for open space preservation. The general operating millage for the city of Ann Arbor is a little more than 6 mills.

The solid waste millage is levied under the Garbage Disposal Plants Public Act 298 of 1917. It allows a city council to levy up to 3 mills of tax for the purpose of “collection and disposal of garbage in the city.” The amount has decreased from 3 mills due to the Headlee Amendment, according to city assessor David Petrak, and has been levied at least since 1980 – which is as far back as his records go.

Solid Waste Fund: Commodity Sales

In addition to the revenue from the solid waste tax levy – which shows up as “CITY REFUSE” on tax bills – the solid waste fund receives revenue from the sale of recycled commodities that are collected through the city’s recycling program. The revenue is conveyed to the city under terms of a contract between the city and ReCommunity, the private contractor who operates the city’s materials recovery facility (MRF).

At their Feb. 25, 2013 work session, council members had been presented with a breakdown of all the city’s major funds, including the solid waste fund – which included the revenue picture for recyclable commodities. Expressed in millions of dollars, here’s the breakdown.

FY10 FY11 FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15

Rcyclng Prcssng Crdt 0.3 1.2 1.4 0.6 0.6 0.6

-

McMurtrie was asked at the council’s May 20 meeting to account for the revenue drops in the sale of recycled commodities from the city’s MRF. He explained the decline as stemming from two factors. First, the market has dropped. That is, the price per ton of recycled product has decreased.

The second factor is related to the terms of a contract under which ReCommunity operates the city’s MRF. ReCommunity can pursue additional revenue for itself by accepting recyclables from other communities – but the city receives a share of that additional revenue. In FY 2011 and FY 2012, ReCommunity was able to add significantly to its non-city tonnage, which resulted in a four-fold increase in revenue compared with FY 2010. But as competition with other facilities increased, McMurtrie explained, recyclables that the city’s MRF previously processed from Lansing and Toledo were not being sent to Ann Arbor.

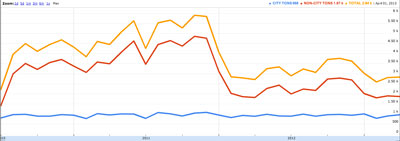

In chart form, the tonnages processed by the MRF (Chart 1) show a clear increase in non-city tons followed by a decrease, while the total tons processed from the city has remained relatively flat. [City tons include amounts from the curbside recycling program, a business dumpster program and a downtown recycling route.]

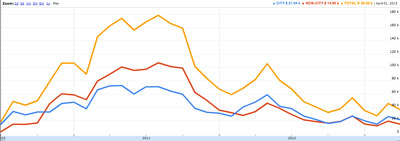

The fluctuation in revenue, due to changing prices in the market for recyclables, is evident in Chart 2 – as the revenue from city recyclables showed an increase followed by a significant decrease, even though tonnages were relatively constant.

Chart 3 illustrates why the total revenue to the city for its recyclable material is roughly comparable to non-city revenue – even though total tonnage is significantly less. Under terms of the city’s contract with ReCommunity, the city receives less revenue per ton for non-city materials than it does for materials collected under the city’s programs.

Chart 1: Ann Arbor MRF tonnage from July 2010 through April 2013. City tons are indicated in blue. Non-city tons are indicated in red. The total tonnage is charted in yellow. (Chart by The Chronicle with data from the city of Ann Arbor)

Chart 2: Ann Arbor MRF revenue from July 2010 through April 2013. Revenue from city recyclables is indicated in blue. Revenue from non-city recyclables is indicated in red. Total revenue is indicated in yellow. (Chart by The Chronicle with data from the city of Ann Arbor)

Chart 3: Ann Arbor MRF per ton revenue from July 2010 through April 2013. Revenue per ton for city recyclables is indicated in blue. Revenue per ton for non-city recyclables is indicated in red. (Chart by The Chronicle with data from the city of Ann Arbor)

Commodity Markets

The overall numbers presented in Charts 1-3 make clear that the commodity markets for recyclable materials fluctuate.

Commodity Markets: ReCommunity’s Glass

This spring, the city’s MRF experienced a specific negative impact to revenue, due to the loss of its contract with its purchaser of recycled glass – Reflective Industries. In an early June conversation with The Chronicle, city solid waste manager Tom McMurtrie and environmental coordinator Matt Naud described how the recycled glass material is now being sold to the landfill where the city tips its garbage. It’s used as daily cover for the other trash and for construction of landfill road bed.

The economics of that scenario work out as follows. Previously, Reflective Industries was paying $4 per ton for recycled glass. The landfill used by the city, Woodland Meadows in Wayne, Michigan, is paying $1.50 per ton, a loss of $2.50 per ton. Under this arrangement, the city is still saving the $26/ton tipping fee charged by the landfill. So instead of a $30/ton net gain compared to simply throwing all the glass away, the city is only seeing a $27.50/ton net.

The Chronicle spoke by phone with Mike Csapo, chair of the Michigan Recycling Coalition’s policy committee and general manager of the Resource Recovery and Recycling Authority of Southwest Oakland County, which operates a MRF. The interview covered a range of issues, including fluctuating commodities markets. Csapo indicated it’s not uncommon that a MRF will periodically have to resort to selling recycled glass to a landfill, or even paying someone to take it away.

The Chronicle was not able to confirm a specific reason for the decision by Reflective Industries to drop the Ann Arbor glass contract. However, ReCommunity – which operates Ann Arbor’s MRF – is currently in talks with Strategic Materials Inc. about picking up the contract.

In a mid-June email responding to a query from The Chronicle, Strategic Materials chief operating officer Curt Bucey indicated optimism about reaching an agreement, but wrote that nothing would be finalized until the glass mixture from ReCommunity’s Ann Arbor MRF is assessed for quality. “[Glass] is highly variable when it comes out of a MRF. Some do a good job cleaning up the glass and some MRFs count on us cleaning it up. … ReCommunity does a better job than most.”

Commodity Markets: Sourcing Glass Walkways

Strategic Materials is set up to process recycled glass from municipal MRFs. But other companies are looking to source material of a quality and shape that a municipal MRF would have difficulty achieving. For example, FilterPave is a Columbia, Missouri firm that uses relatively finely ground recycled glass, in combination with an organic polyurethane made by BASF, to create pathways for pedestrian and light vehicles. The result is a porous surface that can help in applications where stormwater management is a concern.

The FilterPave product was used in last year’s capital improvements to the walkways at Leslie Science and Nature Center (LSNC) in Ann Arbor.

FilterPave product manager Tim Killday told The Chronicle in a phone interview that the glass for the LSNC project was likely sourced from either California or Wisconsin. Why not from Ann Arbor’s MRF? Killday indicated that the end product from any municipal MRF would likely not be suitable for a FilterPave application – without a significant additional capital investment by that MRF.

It’s an ongoing interest, Killday said, for FilterPave to establish more regional connections, so that the recycled glass component of the product can be obtained from a source that is closer geographically to the project site.

Commodity Markets: Glass Countertops and State Strategy

It can be difficult currently for companies to identify where in Michigan recycled feedstocks for manufacturing are being produced in adequate quantity and quality. In a telephone interview with The Chronicle, chair of the Michigan Recycling Coalition’s policy committee Mike Csapo recounted a situation a few years ago when a California company that makes countertops from recycled glass had considered establishing a Michigan operations. The company had tried to identify possible sources of recycled glass in Michigan, Csapo said, but as he’d tried to provide some assistance it proved difficult to get comprehensive data.

In general, Csapo said, data on the availability of recycled material is not collected at the state level. That contrasts with data collection in other areas of solid waste management, he said, which is actually done fairly well. For example, landfills report their intakes in detail, as do registered composting sites. Michigan’s bottle bill means that part of the container waste stream is very well tracked. But there’s no systematic reporting at the state level from municipal MRFs, Csapo said.

Csapo contrasted the amount of detail that economic development agencies typically can provide in other areas compared to recyclable resources. Any economic development agency “worth its salt,” he said, could tell a company looking to locate on a property what liens might exist, what the access to utilities and other infrastructure is like, or what the average disposable income is in the area. But typically they aren’t able to say anything about the availability of recyclables as feedstocks for industry, he ventured.

Commodity Markets: Roads and State Strategy

While Csapo calls data collection “just Management 101,” another angle, besides information gathering, is to look at various specifications in Michigan industries – for example, road building – that might pose barriers to creating markets for recyclable products.

Matt Flechter, Michigan Dept. of Environmental Quality’s recycling/composting coordinator, told The Chronicle in a phone interview that he’s working with the Michigan Dept. of Transportation (MDOT) to look at road building specifications, with the idea of allowing material from rubber tires to be included in the specifications. It’s possible that recycled glass and shingles might be considered as road-building materials in the future.

That way, county road commissions would be able to incorporate recyclable material into local road projects.

Commodity Markets: Executive, Legislative Roles

Flechter also indicated that besides data gathering and removal of barriers to market creation, he’s also looking at the fact that only 24 of Michigan’s 83 counties offer home recycling programs that are classified as “convenient.” There aren’t enough drop-off stations or enough curbside recycling programs statewide, he said.

Flechter and other MDEQ staff are working under the direction of a special message from Gov. Rick Snyder on energy and the environment to improve the situation [emphasis by The Chronicle]:

When we can redirect trash to productive use, we reduce the impact on our lands, air and water. And that’s why this is an area in which we need to do better. As a state, we have one of the lowest recycling rates in the Midwest. We need to look beyond our recycling of cans and plastic bottles and creatively figure out what we can do to reduce our waste overall. This year, my administration will examine possible options to get Michigan to where it needs to be on recycling, and I’ll be coming back to you with a comprehensive plan in 2014.

But some legislative efforts may in fact have counter-intuitive impacts on recycling programs.

For example, Michigan Sen. Rebekah Warren, whose 18th District includes Ann Arbor, recently sponsored a proposal (SB 0432) to expand Michigan’s bottle bill. Currently, consumers pay a deposit when they purchase beverages in certain types of containers. The deposit is returned when the container is returned to a store selling that type of beverage. Warren’s proposal would expand the types of containers included in the system – to include those for bottled water. Michigan Rep. Jeff Irwin, whose 53rd District includes most of Ann Arbor, is helping to sponsor a similar piece of legislation (HB 4198) in the state House.

In a comment left on Warren’s website, as well as in a phone interview with The Chronicle, Mike Csapo argued that expanding the bottle bill could have a negative impact on municipal recycling programs: “If you want to harm curbside recycling and municipal programs in Michigan, expand the bottle bill. That will take valuable materials away from our curbside programs.”

Csapo told The Chronicle that based on numbers he’d looked at a few years ago for the MRF he manages, clear plastics like those that go into bottled water containers make up 2% of the recycling stream, but account for 6% of revenue. If a bottle return law starts diverting those containers from local recycling facilities to a different stream, that would have a negative financial impact on the viability of local recycling programs.

In a June phone interview, Irwin said he gave more weight to the argument for the expanded bottle bill based on scenic beauty and the need to reduce litter from bottled water containers. The original bottle bill had been very effective in reducing litter – on roadsides and beaches. And he felt that the increasing prevalence of bottled water containers could be stemmed with a bottle bill expansion. Still, he acknowledged that it’s worth considering how to integrate that additional plastics stream into a more general state economic development strategy.

One of the recommendations in Ann Arbor’s draft solid waste plan is also based in part on a desire to reduce litter – specifically from single-use plastic bags. The recommendation is to implement some kind of fee that consumers would have to pay for a single-use bag.

That recommendation differs from an ordinance that appeared on the Ann Arbor city council’s agenda several times four years ago – which would have imposed a ban. The proposal had been brought forward by then-Ward 2 councilmember Stephen Rapundalo, but did not receive even an initial vote by the council:

- July 21, 2008: Plastic bags ordinance postponed at first reading.

- Oct. 6, 2008: Plastic bags ordinance postponed at first reading.

- March 2, 2009: Plastic bags ordinance postponed at first reading.

- June 1, 2009: Plastic bags ordinance postponed at first reading.

- Sept. 21, 2009: Plastic bags ordinance tabled at first reading.

Diversion Rates

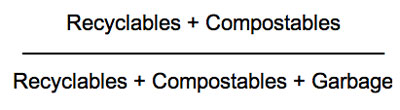

A central goal of the draft five-year solid waste plan is to increase the “diversion rate.” The diversion rate is the total of recyclables and yard waste collected, divided by recyclables, yard waste and garbage:

For single-family residential, the goal is to increase the diversion rate from 50% to 60%. For the last six fiscal years starting in FY 2007, here’s what the single-family diversion rate looks like:

07 08 09 10 11 12 41% 54% 43% 50% 50% 49%

-

From the formula, it’s clear that one way to increase the diversion rate is to move materials represented in the denominator to the numerator: Get more of the material that can be recycled out of the garbage stream and into the recycling part of the equation.

Diversion Rates: Less Garbage, More Recyclables

According to the draft five-year plan, based on a sorting of trash from 96 randomly selected households in the fall of 2012, about 12% of the content of garbage trucks collecting residential routes could be placed in recycling carts instead.

That means there’s room for improvement – beyond the increase in recycling that the city’s numbers show after the city implemented a single-stream system in September 2010. That program replaced two tote bins with a single, large wheeled cart.

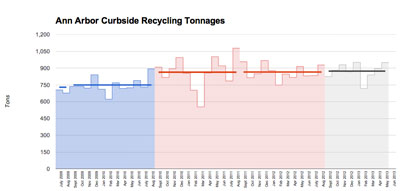

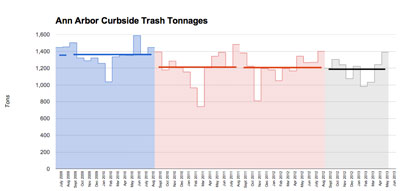

In Charts 4 and 5 below, the blue area covers a period preceding the single-stream system. The pink area covers the first two years of the single-stream system, which included a coupon incentive program administered by RecycleBank. The city council did not appropriate funding for the RecycleBank contract when it set the FY 2013 budget at its May 21, 2012 budget meeting. So the RecycleBank contract ended as of September 2012. The period after the cancellation of the contract is shown in gray. The horizontal bars are the average for each period.

There was some concern that discontinuing the RecycleBank incentive coupon program could lead to the erosion of gains made since the introduction of single-stream recycling. But the numbers so far don’t appear to show any erosion of the increase.

Chart 4: Ann Arbor Curbside Recycling Tonnages. The blue area represents a time period before single-stream recycling was implemented. The pink area is the two-year period of single stream plus a RecycleBank coupon incentive program. The gray area represents single stream after the RecycleBank contract was cancelled. (Chart by The Chronicle, from data provided by the city of Ann Arbor.)

Chart 5: Ann Arbor Curbside Trash Tonnages. The blue area represents a time period before single-stream recycling was implemented. The pink area is the two-year period of single stream plus a RecycleBank coupon incentive program. The gray area represents single stream after the RecycleBank contract was cancelled. (Chart by The Chronicle, from data provided by the city of Ann Arbor.)

Diversion Rates: Less Garbage, More Compostables

Another way to move material in the diversion rate equation is to take it out of the garbage and move it to compostables.

That’s the approach another recommendation in the five-year draft solid waste plan would take – by expanding the range of materials that are accepted as part of the brown compostable cart collection system. The recommendation is to include all plate scrapings in the compostables program. Based on a sorting of trash from 96 randomly selected households in the fall of 2012, about 50% of the material Ann Arborites put in the garbage is food waste.

Moving that material into the compostables category would have a positive impact on the diversion rate. If that move proves to be successful, it could also set the stage for reduced frequency in garbage collection – if the recommendations in the five-year plan are followed.

Can plate scrapings be accommodated into the city’s compost processing operation? That operation is managed by WeCare Organics, a private company under contract with the city. The Chronicle spoke by phone with Mike Nicholson, senior vice president at WeCare Organics, who indicated optimism that WeCare was already well positioned with the equipment needed to allow successful composting of plate scrapings as a part of the Ann Arbor operation.

Nicholson pointed to two pieces of equipment that WeCare now deploys on the site – a Doppstadt grinder and a Komptech windrow machine – that would ensure that plate scrapings would decompose as they should, along with the rest of the mix. A key to the speed of a composting process, like any chemical reaction, Nicholson pointed out, is increased surface area. That’s achieved through the kind of grinding done by the Doppstadt machine.

In giving a positive outlook on WeCare’s ability to incorporate plate scrapings into its current operation, Nicholson also pointed to the relatively small amount of the total composting stream that food waste would make up – perhaps 5-10% of it.

Taking plate scrapings out of the garbage and putting them into the compost cart would clearly have a positive impact on the diversion rate. But what if a resident started adding leaves and grass clippings to the brown cart that were previously mulched into the grass as it was mowed or composted on site in a backyard? Wouldn’t that scenario also have a positive impact on diversion rate?

In his phone interview with The Chronicle, Mike Csapo allowed that the statistic could be influenced upwards if people put grass clippings into the brown carts that they previously mulched in place. In the industry it’s assumed that resident behavior with respect to how they treat yard waste is likely to remain fairly stable or change only slowly. The idea behind the statistic, he said, is to make some attempt at standardizing for the sake of comparison across communities – but he cautioned that a pure apples-to-apples comparison is very difficult.

The diversion rate still measures success in terms of the basic question, Csapo noted: If we’re going to pick something up at the curb, are we just going to bury it, or will we utilize it for something?

Coda

Although the solid waste plan update was in some sense “buried” under the council’s spring work load this year, it will be unearthed again in the fall. It’s unlikely that the contents of the draft plan and its accompanying appendices will have decomposed much by then.

It’s worth noting that adopting the plan would not authorize the implementation of recommendations in the plan. The council would need to vote separately on any funding or legislation to implement specific aspects of the plan.

[Waste Less: City of Ann Arbor Solid Waste Resource Plan.] [Appendices to Waste Less]

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of the ins and outs of solid waste. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

When, oh when will the city pay any attention to its infrastructure???

Oh wait, it’s doing that. All the time.