In the Archives: Soap a Sign of Spring

In spring the Washtenaw pioneer farm wife prepared for arguably the smelliest, most dangerous, and most tiring chore of the year. Along the way, she could suffer chemical burns, ruin her clothes, or accidentally start a grease fire. The process was hours long, involved seemingly endless stirring, and often failed.

Her first step was to gather scraps of skin and fat left over from last fall’s butchering and the grease and bones saved from months of cooking. Often rancid and mixed with dirt and animal hair, the fats were combined with water in a big iron kettle outdoors and boiled over a fire. Upon cooling, the congealed floating layer of somewhat cleaner fat was skimmed off and saved.

Along with fats, wood ashes had been conserved for some months. Ashes went into the outdoor wooden ash hopper. The hopper was a large V-shaped trough, a barrel with a hole in the bottom, or even a hollow log set upright. A pad of straw at the bottom of any style of hopper helped retain the ashes. Water poured over the gray powdery mass seeped through to become caustic alkaline lye that trickled out into a collection bucket.

Lye was the wild card in this endeavor; upon its strength depended the success of seat-of-the-skirt pioneer chemistry. Lacking pH test strips or a digital scale, the pioneer woman tested the lye by dropping in an egg or potato – if it floated, the lye was thought to be sufficiently caustic. Another test involved dipping in a feather; if the lye dissolved the feathery bits from the quill, it was dangerous enough to be useful. In an era before rubber gloves or cheap safety goggles, even a small spill or splash could cause severe skin or eye damage, with hospitals, if any, perhaps miles distant.

The fat and lye was put in the kettle and heated and stirred for some hours until the combination thickened into a soft brownish soap, a process called saponification. The process sometimes failed. “Much difficulty is often experienced by those who manufacture their own soap,” noted the November 21, 1835 issue of the Rochester, New York-published Genesee Farmer. “Often when every precaution has been apparently taken, complete failure has been the consequence; and the time is not long past when some have even declared that they believed their soap was bewitched.”

Cooled and packed in stoneware crocks or barrels, the soft soap would serve as the family supply for the coming year. Bar soap could be made by adding salt to the cooking soap, pouring it into wooden trays, allowing it to set, and cutting the hardened slabs into bars. Given the added expense of salt and time, most pioneers opted for soft soap. Its slipperiness led to the figurative use of the term “soft soap” to mean “flattery” as early as 1830, per the American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms.

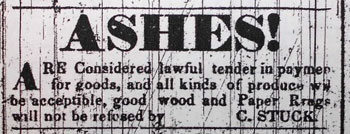

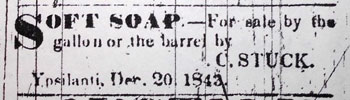

Considering the difficulties associated with soap making, it’s small wonder that larger-scale soap manufactories were among the county’s first industries. As early as 1843, just two decades after a handful of settlers drifted into Woodruff’s Grove, Ypsilanti merchant Charles Stuck was placing ads in the Ypsilanti Sentinel requesting ashes and offering soft soap by the gallon or barrel. In 1844, Ypsilanti storekeepers Norris and Follett accepted ashes, barrel staves, firewood, “and other country produce” as the equivalent of cash for items in their store.

In 1855 Andreas Birk, an immigrant from the onetime German Empire’s southwestern state of Wuerttemberg, established a soap and candle factory on the corner of Madison and Main streets in Ann Arbor, piping in water from a nearby spring. By 1881, according to Chapman’s History of Washtenaw County, the building was two stories tall and measured 30 by 93 feet. In 1880, he had $1,500 invested in the business, employed four people, and produced $4,000 worth of product (about $94,000 in today’s dollars). Birk had a satellite office in Ypsilanti and a circulating ash-wagon.

Ypsilanti merchant Mark Norris, unlike today’s Meijer or Target, accepted wood ashes as cash payment.

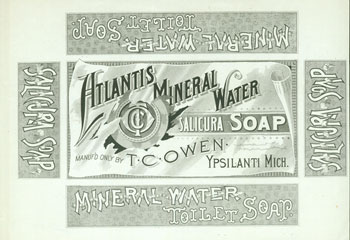

For decades Birk was one of two Ann Arbor soapmakers, the other being Daniel Millen at the northern end of State Street. In 1880, Millen’s soap and candle works represented a $1,800 investment, employed three men, and produced $2,480 worth of soap and candles ($58,000). Birk’s factory was eventually named the Peninsular Soap Co., and Millen’s the Ann Arbor Soap Works. In the mid-1880s Ypsilanti the would-be water baron Tubal Cain Owen also began manufacturing soap, using his much-touted mineral water. He adorned his hefty bars of Salicura Soap with ornate wrappers.

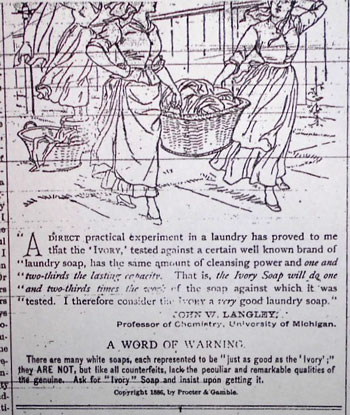

By the late 1880s, new advertisements portended change. The first ads for Cincinnati-made Ivory and Chicago-made Santa Claus soaps appeared in Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti papers. In contrast to plainer local ads whose graphic design consisted largely of varied fonts, the new soap ads looked slick and professional, with elaborate images and in Ivory’s case, bubbly doggerel.

One Ivory ad in a September 1889 issue of the Ypsilanti Commercial depicted washerwomen near a clothesline and contained an endorsement by onetime UM chemistry professor James Langley. He had resigned from the university some months prior. “A direct practical experiment in a laundry has proved to me that the ‘IVORY,’ tested against a certain well-known brand of laundry soap, has the same amount of cleansing power and one and two-thirds the lasting capacity,” wrote the Harvard graduate. “I therefore consider the IVORY a very good laundry soap.”

Others apparently did as well, and local soapmakers suffered. By 1897, the Glen V. Mills city directory for Ann Arbor-Ypsilanti listed no local soap manufacturers. A state gazetteer of the same year listed only 18 soapmakers for the entire state, with eight soap makers in Detroit, four in Grand Rapids, and one each in Albion, Bay City, Houghton, Jackson, Portland, and Saginaw.

Michigan continued to contribute to the soap industry, though in an unusual way – as the wreckage left behind by rapacious lumbering became a salable product. The Sept. 1, 1892 issue of the “American Soap Journal and Perfume Gazette” noted, “[T]he manufacture of [wood ashes] is still carried on . . . [in] the forests of Northern Michigan, and in portions of the Provinces of Canada, this substance is still systematically manufactured the year through. The hardwood stump lands from which the timber trees have been cleared are thus made to contribute a second time to the benefit of the settlers.”

Soap was one of the first mass-produced, nationally-advertised products, along with cigarettes, baking powders, and canned foods. Its success allowed such manufacturers as Colgate-Palmolive, the British Lever Brothers (later Unilever) and Ivory manufacturer Procter and Gamble to be early and prominent sponsors of the 1930s radio dramas called “washboard weepers” or “soap operas.”

Ypsilanti mineral water entrepreneur Tubal Cain Owen emphasized that his Salicura soap contained beneficial substances from his miraculous murky water.

Modern-day craft soap making can be a dramatic production as well. Even given such conveniences as mail-order food-grade lye of a known concentration, cheap-ish Costco canola and olive oil, and library books with time-tested recipes, the aspiring soap maker must assemble quite a suite of ladles, scrapers, bowls, molds, oils, safety equipment, measuring cups, colorants, essential oils for fragrance, Solo cups for color-mixing, old towels, candy thermometers, a digital scale, a non-aluminum stock pot, a stick blender, a giant tub to keep it all in, and a tolerant spouse. Many items can be gleaned from dollar or thrift stores – bravery concerning the lye must be summoned from within.

The end result in this author’s fumbling foray was a barely-solid slab with a hue less leafy freshness than a moldy pallor. The scented slab, due to a slight measuring error, reeks with a lilac gut-punch that nearly makes the eyes water. The eyes of pioneer foremothers, were they to see this saggy soap, would likely water as well, with laughter. No fancified folderol was needed for the resourceful local ladies, whose determination transformed moldy bacon and a handful of ashes into a squeaky-clean home, wardrobe, and family.

Mystery Artifact

Last month, competition really heated up and guessers cooked up intrigue!

Clearly Cosmonican, ABC, Ray Hunter, and Philip Proefrock knew that the item in question was a stovepipe flue or damper.

Stovepipes used to be custom-made from sheet metal, often by the hardware store proprietor, and the flue was inserted as the pipe took shape.

The movable device helped regulate the draft, or upward current of air, that affected the rate at which the stove burned. Congratulations to the guessers (and thank you for the puns)!

This time we have a small brass object that has modern analogs still in use. How would this have been used in the past, and by whom? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales of the Ypsilanti Archives” and “Hidden Ypsilanti.” You can reach her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

This one’s too easy. I’ll let others take a crack.

Very clever of you, Laura, to tilt the mystery object on its side. Its proper orientation is with the solar collector lens facing upwards to capture the sun’s rays, where they are stored in the attached canister. Modern versions have been adapted to collect radio waves from outer space. Waves of either kind can be dumped out of the canister for later use, which actually have a kind of grayish lumpy texture after they’ve undergone transformation in the canister. They might be mistaken for ashes, but I suppose it goes without saying that you can’t make soap out of sunshine … even though both have certain cleansing properties.

It’s a good thing you are ineligible, Dave! Laura, I now have new respect for my fireplaces ashes and will save them carefully.

Jim: Hopefully readers can dig up the answer!

Dave: The mystery object looks fairly old…but then solar energy collection is as well; the first recognized solar panel of sorts was invented in 1767: [link]

Joan: Hardwood ashes were preferred for soapmaking; things like pine were seen as comparatively low-grade. So if you have an antique walnut or mahogany dining room table lying around, that would be ideal. Thank you for reading!

Not sure, but it looks like it could be a railroad signalman’s kerosene lamp, or for lighting in a mine.

Cosmonican: I should include a ruler in these photos and will do so in the future. It’s about 6 inches tall. Thank you for reading!

Take the lid off the top, add a few grains of CaC2, mix with H2O…you will be enlightened! You can hang your hat on that…or vice versa!

C2? What is that? Doesn’t sound like any salt I am aware of. C is of course elemental carbon but the notation suggests that this is the base component of an acid. Carbonate? CO3?

Baking soda is CaHCo3. The H indicates that the two valences of calcium are supplemented by a hydrogen atom to match the three negative charges of the carbonate ion.

Probably this is now junior high chemistry, so I offer it with proper humility.

carbide lamp

You city folks just need to get out more. Loretta Lynn or “Tennessee” Ernie Ford would know all about this item.

The “2″ is supposed to be a subscript. I’ll attempt it here, although I am not fully confident of The Chronicle’s utf-8 support: CaC₂

Is that intended to be calcium carbide? [link]

Looks as though it could be explosive.

Calcium carbide is correct, when mixed with water, it is indeed explosive, but when controlled it can be illuminating.

a/k/a: “Limelight”?

Not quite limelight, but close. When I was a kid growing up in a small mining town in Pa, we would use carbide to make our own 4th of July firecrackers. Just take an old empty gallon paint can, put a nail hole in the lid, put a few grains of carbide in the can along with a little bit of water…then shake the can…touch a flame to the nail hole and BOOM!

Fred: One of these artifacts is pictured on the new Lewis Hine “Made in America: Building a Nation” series of postage stamps (which are quite beautiful!)

I am enjoying the discussion going on and I appreciate learning new information. Interesting info! Thank you to Ray, Vivienne, and other readers for their comments.