Column: Good News for Book Artists

A group of people in this city care so much about the art of making books that they’ve launched a center dedicated to it, one that will pass down an artistic tradition while incorporating cutting-edge technologies to widen its boundaries.

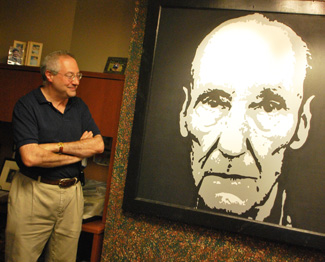

Printmaker Jim Horton at the boundedition studio on May 16 with his Chandler & Price letterpress, made in Cleveland in the 1930s.

Its founders call boundedition a “member-based community resource for the preservation, practice and expansion of the book and paper arts.” They call themselves its managing members: bookseller Gene Alloway, book artist Barbara Brown, graphic designer Laura Earle, printmaker Jim Horton, and product designer Tom Veling, a retired Ford Motor Co. engineer.

They were moved to act when Tom and Cindy Hollander announced last summer that Hollander’s School of Book and Paper Arts would close its doors after the spring 2013 session. The school operated on the lower level of the Hollander’s Kerrytown store for more than 10 years.

Brown, a longtime teacher of bookbinding classes at Hollander’s, reached out to fellow teacher Horton as well as Earle, Veling and others who met weekly at the open studio there. Serious discussions began in February, Horton says, when “we decided that what we’d done at Hollander’s was too good to give up.”

Earle, whose family has been involved with Ann Arbor’s Maker Works, was instrumental in finding a home for boundedition inside the member-based workshop at 3765 Plaza Drive. Maker Works’ managers were receptive to letting boundedition rent some space, and Brown says Earle, her husband and her son “pretty much built the office singlehandedly” – including a set of modular work tables that can be arranged according to the requirements of individual classes.

Brown credits Earle’s energy and determination for the speed with which boundedition took shape. “It would have happened,” she said, “but Laura made it happen now instead of later.”

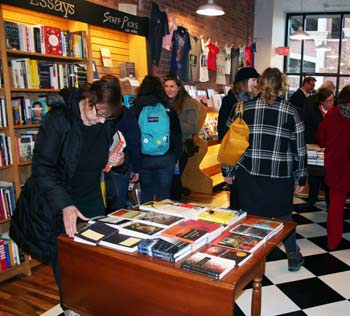

Ann Arbor’s community of book artists and book lovers got a chance to look around at a May 16 curtain raiser. Tom and Cindy Hollander were in attendance; Horton reports that they’ve given boundedition “a thumbs up” and Brown says “Tom has really been very supportive.”

An open house is coming up on Sunday, June 2, from 1-6 p.m. “The whole community is invited to come out to see the space,” Horton says, “to sign up for classes, to let us know if they’re interested in teaching classes.” [Full Story]