In the Archives: Soap a Sign of Spring

In spring the Washtenaw pioneer farm wife prepared for arguably the smelliest, most dangerous, and most tiring chore of the year. Along the way, she could suffer chemical burns, ruin her clothes, or accidentally start a grease fire. The process was hours long, involved seemingly endless stirring, and often failed.

Her first step was to gather scraps of skin and fat left over from last fall’s butchering and the grease and bones saved from months of cooking. Often rancid and mixed with dirt and animal hair, the fats were combined with water in a big iron kettle outdoors and boiled over a fire. Upon cooling, the congealed floating layer of somewhat cleaner fat was skimmed off and saved.

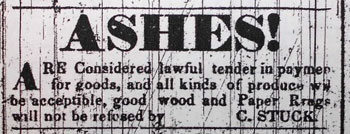

Along with fats, wood ashes had been conserved for some months. Ashes went into the outdoor wooden ash hopper. The hopper was a large V-shaped trough, a barrel with a hole in the bottom, or even a hollow log set upright. A pad of straw at the bottom of any style of hopper helped retain the ashes. Water poured over the gray powdery mass seeped through to become caustic alkaline lye that trickled out into a collection bucket.

Lye was the wild card in this endeavor; upon its strength depended the success of seat-of-the-skirt pioneer chemistry. Lacking pH test strips or a digital scale, the pioneer woman tested the lye by dropping in an egg or potato – if it floated, the lye was thought to be sufficiently caustic. Another test involved dipping in a feather; if the lye dissolved the feathery bits from the quill, it was dangerous enough to be useful. In an era before rubber gloves or cheap safety goggles, even a small spill or splash could cause severe skin or eye damage, with hospitals, if any, perhaps miles distant.

The fat and lye was put in the kettle and heated and stirred for some hours until the combination thickened into a soft brownish soap, a process called saponification. The process sometimes failed. “Much difficulty is often experienced by those who manufacture their own soap,” noted the November 21, 1835 issue of the Rochester, New York-published Genesee Farmer. “Often when every precaution has been apparently taken, complete failure has been the consequence; and the time is not long past when some have even declared that they believed their soap was bewitched.” [Full Story]