Column: Arbor Vinous

Man does not live by wine alone.

Indeed, prudence dictates frequent hydration breaks when consuming a significant quantity of any alcoholic beverage.

And George McAtee – “I’m like a water sommelier” – hopes you’ll pour your next chaser from one of the clear Bordeaux bottles he hand-fills with artesian spring water, sourced 150 feet under McAtee Organic Farms, in western Washtenaw County, near Grass Lake.

Supplier of Michigan’s only water sourced and bottled on a registered organic farm, McAtee is critical of both municipal water systems and large, commercial water producers, which he terms “commodity bottling.”

Though his farm’s faucets flow with the same water he bottles, he adamantly tells a visitor, “Don’t call my water tap water!”

“I make an expensive water, compared with municipal water,” he notes. “but they’re two different products.”

What’s the distinction? “I have a known source, I don’t put any chemicals in it. It doesn’t run through four miles of pipe.”

McAtee calls municipal water “potable” for a healthy person like himself. But “if I were a pregnant woman, I would not drink city water.” Similarly, children and the elderly are “vulnerable because of their immune systems and ages.”

“They treat with many chemicals, chemicals that are sanitizers. If you ingested them directly, it would kill you. They outlawed the chlorine bomb, but that’s the main ingredient for sanitation in a public water supply.”

“A public water supply is like a spider web. They have to treat it enough so when it reaches the very furthest guy down the pipe, his water has to be safe. So in between, people are getting many different amounts of chlorine.”

He speaks of a friend who painted water supply tanks and removed “bushels and bushels of dead birds.”

“It’s why they chlorinate so hard. When they test it, and they see bacteria, they put more chlorine in it. A lot of times, you can test for chlorine in a municipal system and it’s over the legal limit. It’s happening more and more and more, because the systems are older and older and older. When you take a glass of water and you smell chlorine, you are probably over the limit.”

But some of his harshest words are reserved for “commodity” water bottlers.

“Some companies bottle ‘purified.’ Purified generally is municipal water that’s been filtered and had a synthetic, manmade mineralization added back in – that’s called ‘polishing’ – for flavor and texture and uniformity in their water.”

He notes that both Coke’s Dasani and Pepsi’s Aquafina originate with Detroit’s municipal water. “You’ll hear the people who work for the Detroit water system tout that it’s one of the best water systems. I don’t share that opinion.”

“But Dasani tastes different from Aquafina – for a reason. They strip it with absolute filtering of all the nutritional value it’s got” before adding back their proprietary mineral blends.

A large and powerfully built yet surprisingly soft-spoken man in his mid-50s, McAtee is no idealist-come-lately to farming organically; he describes himself as “third generation organic.” Growing up in Grass Lake, he spent weekends and summers in the country, helping his uncle farm the 100 acres he now owns.

“Every chance I got, I would come out here and stay. I’d come out on Friday night and go back on Sunday to go to school. That’s how I became attached; I saw the life cycle of the farm.”

But understanding of the agricultural practices he was absorbing only came gradually.

The original windmill that first brought water to the surface. It's no longer in use. (Photo courtesy of George McAtee.)

“My uncle was organic before organic was a trendy term. When I was in fifth grade, a girl came in one day with a tomato. She said it was organic, and I asked what that means. She said no bad stuff was used in growing this tomato. ‘My mom just loves this kind of food. That’s why she buys these special vegetables.’”

“Now, my mom and dad went to the grocery story and bought whatever they wanted, and never looked at a label. But I came out here [to the farm] and said, ‘Uncle Andy, do you know what an organic tomato is?’ And he said yes. And I said, ‘A girl brought an organic tomato in, and she says it’s extra special. Why was that tomato so special?’”

He said, “You don’t know what she was telling you? You’ve been eating food better than that all your life out here. Only a damn fool puts poison on his land and eats from it.’”

In 1992, McAtee purchased the dormant farm from his aging uncle, uncommitted to any plan beyond building a home and hunting on the land. One early experiment – planting five acres of wine grapes – fizzled when the vines failed to survive the winter.

But the cost of land ownership caused him to reconsider.

“I paid my first year’s taxes and said, ‘Wait a minute, I’m writing a check here but not getting very much back.’ The most obvious way, to me, was to develop the water.”

During the 1990s, U.S. bottled water sales grew 30% annually, according to McAtee, making it the world’s fastest-growing beverage market. Knowing the high quality of the farm’s underground aquifer, he wondered about its commercial potential.

Then a chance meeting with a Pepsi executive on a moose hunt in Canada “kind of lit a fire under me.”

“He said, ‘Do it, George. We’re coming out with our own brand of water. The name is Aquafina. We don’t even have the name registered yet.’ That’s how far ahead of the curve that was.”

Still, the better part of a decade would pass before McAtee began to bottle water at what he calls his “prototype” for a larger facility, to be built at an as-yet-undetermined date.

First on the list: replace the open well and elderly windmill that pumped water to the surface at a leisurely 2 gallons per minute, where it was stored in a cement basement cistern.

“At the time they did it, that was the technology of the day. We know now that if mice, snakes, insects fall in it and decay, it can cause a bacterial contamination. Viruses are even worse. That can happen in an open pit system.”

A fortuitous golf connection with a University of Michigan regent – “I helped fix his slice,” explains low-handicapper McAtee – led to an introduction to UM Geology Professor Lynn Walter.

“I showed up to meet with her and she was kind of surprised,” McAtee recalls. “She asked, ‘Where are your people?’ I said, ‘I’m my people.’”

Walter recruited UM colleague Ted Huston for a study that confirmed what McAtee had hoped: the same aquifer tapped by the open well also fed a spring, located elsewhere on the farm. McAtee could sink a new, self-contained underground pump into the aquifer and legally call his product “Artesian Spring Water” – the premium water niche market he hoped to reach.

By 2000, McAtee had completed the well, pumping facility and obtained the necessary state permits – following literally dozens of tests for contaminants.

The “big three” minerals in McAtee water are magnesium, calcium and iron – all present in relatively slight amounts, making the water soft. The water comes from the ground at a perfectly neutral 7.0 pH and undergoes a light filtration for particulate sediment before bottling.

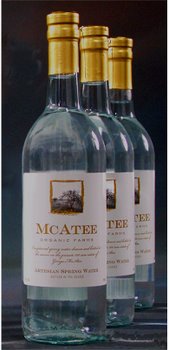

Although he’s used plastic bottles in the past, McAtee currently bottles exclusively in glass “because I can tell the difference. The last thing I want to do is open it up and taste the container.”

Many small wineries use the same kind of hand-bottling machine that George McAtee uses to bottle his artesian spring water.

By using glass, McAtee also avoids possible contamination from the BHA believed to leach from many plastics. “You don’t see plastic test tubes in a lab. You see glass,” he says.

But there’s a downside: the glass bottles, imported from France, are both expensive and heavy to ship compared with plastic. Although McAtee accepts them back for reuse, he estimates that he only recycles a few percent of his total production.

His aquifer’s potential yield is 40 million gallons per year but McAtee, who calls himself a “micro-bottler,” says he pumps only a tiny fraction of that amount. He declines to provide specifics about sales, but the bottling equipment confirms his description: it’s the identical hand-operated machine seen in many boutique wineries.

McAtee also offers some advice for those who don’t buy his water. “If I lived in the city, and I didn’t want to buy water, this what I’d do. I’d get a filter for the tap and I’d get a filter for the ice line on my refrigerator, and I’d faithfully change those filters. Then I’d take that filtered water and put it into a wide mouth pitcher in the refrigerator or on the counter, stir it, and let whatever is in it oxidize.”

Water from McAtee Organic Farms is available locally at Plum Market and Arbor Farms, along with Busch’s in Dexter, Polly’s in Chelsea, Lone Oak Vineyard and Frank’s Shop-Rite in Grass Lake, and Chateau Aeronautique Winery in Jackson. Prices vary but are generally in the $2 to $3 range for a 750 ml bottle.

______________________________________

Later This Month: Passover Wine

At the end of March, the Jewish community observes Passover to commemorate the Egyptian exodus. Even secular celebrants may find themselves plowing through the religiously-mandated four glasses of wine imbibed during a Seder dinner.

While America’s traditional Passover pour is the ultra-sweet Manischewitz Concord Grape (or its made-in-Michigan analogue, St. Julian “Sholom”), Kosher wine availability has exploded in recent years. This Passover, nearly 100 Kosher wines from nine countries grace Ann Arbor’s shelves, at prices from $8 to $80.

Local collector Alan Lampear recently assembled 40 of them, in the $20-and-under price range, to sample under the auspices of Beth Israel Congregation. Although Kosher wines don’t normally enjoy a lofty reputation, several were surprisingly good. Some picks for different tastes:

WHITE

2007 Goose Bay Sauvignon Blanc, New Zealand. Typically dry and grassy. $19-20 at Hiller’s and Village Corner.

2008 Bartenura Moscato, Italy. Slightly sweet and fizzy; a low-alcohol palate-tickler that also appeals to non-wine drinkers. $16-$17 at Hiller’s, Plum Market, Village Corner and Whole Foods.

RED

2007 Ramon Cordova Rioja, Spain. Dry and earthy. $17 at Plum Market and Village Corner.

2008 LanZur Carmenere, Chile. Soft, fruity and highly quaffable. $8.50 at Village Corner.

2007 Yarden “Bordeaux Blend” (Cabernet Sauvignon / Merlot / Cabernet Franc); Galilee, Israel. Dry, surprisingly Bordeaux-like in style. $14-$15 at Morgan & York, Village Corner and Whole Foods.

About the author: Joel Goldberg, an Ann Arbor area resident, edits the MichWine website and tweets @MichWine. His Arbor Vinous column for The Chronicle is published on the first Saturday of the month.

Hmmm…I wonder how beer would taste if made with his water. To my palate, there is a difference b/w Arbor Brewing beer and Corner beer and I understand that is largely due to water differences. They both taste awesome, but my favorite IPA has a slightly different taste. It’s hard to describe, but I know it when I taste it. It would be interesting, albeit cost prohibitive for me, to brew with something like this and see how the water affects the taste….

PS: Can’t wait to drink Passover wine with you, friend! :)

To Teacherpatti,

If you want to make some beer with my artesian spring water, that would be fine. Bring your containers to my farm and I’ll fill them for free.

You make the beer and share back with me. How’s that!

Email me and leave your cell number and I’ll call you to set up an appointment. Sounds like your friends with Joel….bring him with you, if you like.

George McAtee