In the Archives: The Male Suffragette

Editor’s Note: With primary election season starting to warm up, and an exhibit on suffrage planned for this coming winter at Ann Arbor’s Museum on Main Street, local history columnist Laura Bien takes a look back at the history of the local suffrage movement.

“Baby suffrage” is what one Detroit newspaper proposed in 1874. In that year, Michigan voted on whether to remove the word “male” from a part of its Constitution related to voting. The paper sneered that infants voting in polling booths would be the next step if women were given the vote.

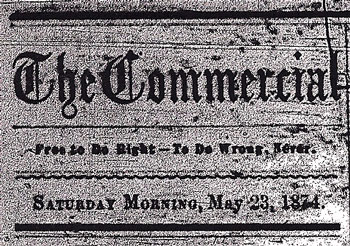

Charles Rich Pattison chose as his bold motto for The Commercial "Free to Do Right: To Do Wrong, Never."

Newspapers of that era often served as explicit vehicles for their editors’ opinions and prejudices. As they did with the Temperance issue, papers across Michigan chose a side in the suffrage question in the key year of 1874.

Their pro- and anti-suffrage positions reflected the divided opinions not just on the national level, but, as in Ypsilanti, on a municipal level.

Edited by Charles Woodruff, the Ypsilanti Sentinel was against suffrage for women. It regularly published editorials that disparaged the idea and disparaged the Sentinel’s competing paper, The Commercial, which was led by arguably the most outspoken editor in Ypsilanti history.

Charles Rich Pattison was born in New York in 1824. His father, Samuel Warren Pattison, and mother, Phebe Atwood Pattison, brought him to Michigan Territory when he was 12 years old. According to Charles Chapman’s 1881 History of Washtenaw County, “from 1836 to 1840, he devoted his time to fishing and hunting and clerking in a store.”

Pattison was educated at home and by age 17 was teaching in a nearby school. After more work as an educator and school principal, Pattison became a University of Michigan student at age 22. He was a member of the literary society Alpha Nu and for three years edited the literary journal Sibyl.

After graduation, Charles studied at Newton Theological Seminary in Massachusetts. He graduated in 1853 and served as pastor in Baptist churches in Pontiac and Grass Lake. He married Ellen Frey in 1854.

On January 1, 1864, at age 40, Pattison bought the office and printing equipment of an Ypsilanti paper called the Herald. He began publishing the True Democrat, later renamed the Commercial.

The Commercial reflected the former Baptist pastor’s pro-Temperance, pro-suffrage opinions. The paper succeeded, and Charles moved into a larger printing house at the southeast corner of Cross and Huron streets.

At times, the office seemed more like a fortification, and Pattison less an editor than a large piece of artillery firing blasts at saloon-keepers, advocates of standard time, and his arch-nemesis, editor Woodruff at the Sentinel.

“The most absurd charge ever trumped up,” said Pattison in the May 30, 1874 Commercial, “is that ‘Free Love’ so called has anything to do with woman suffrage. No man, unless innately depraved, would make such a base charge.”

Pattison continued, “Says the Sentinel, ‘Is not [free love advocate] Victoria Woodhull in favor of woman’s suffrage?’ No doubt of it. It is the only subject in regard to which she seems to indicate any soundness of mind.” Pattison wound up his editorial with one last blast at Woodruff. “His real trouble is that if the women vote they will smash his darling idols, the saloons.”

Pattison attacked the Sentinel again, on June 20, 1874, for allegedly misrepresenting the pro-suffrage publication, the Woman’s Journal.

“Our contemporary exhibits his general misanthropy by misquoting [and] distorting sentences in the Women’s Journal. He knows, for he is not altogether inane, notwithstanding his knavish propensities, that the entire tenor of the Woman’s Journal is in favor of the highest cultivation of domestic and marital ties, the ennobling of these rather than their abolition.

“The Sentinel has an amazing affinity for Victoria Woodhull,” Pattison continued. “It can’t let the poor woman alone. If a copy of her paper can be found it turns up in the Sentinel office. The advocates of woman suffrage in Michigan don’t affiliate in that direction and don’t keep track of such journals. The Sentinel naturally gravitates to carrion as a starving man does to food.”

When suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton took an 1874 tour of Michigan, she spoke in Jackson Prison, Ypsilanti, Detroit, and other spots. “The Detroit Post is in tantrums about Mrs. Stanton’s canvass of the State,” Pattison said in the June 6 Commercial. “It copies every miserable slimy slander in regard to her speeches. Mrs. Stanton’s speech in [Ypsilanti] was entirely unexceptionable. It was mild, persuasive, eloquent, argumentative, and convincing … Common sensed men will reason that a cause that can only be met by innuendo and misrepresentation must be based on the rock and worthy their confidence.”

Pattison was not the only pro-suffrage man in town. Another was Professor Estabrook, the head of Normal College (Eastern Michigan University) and a regent of UM. “[His stance on suffrage] has significance as he is one of the leading educators in the State,” said Pattison in the July 11 Commercial. Many local clergymen also supported the cause, according to Pattison. “A large proportion of our ministry, especially in the Methodist and Baptist churches, are in favor of woman’s suffrage,” he said in the May 9 Commercial.

Pattison wrote a letter to the Governor of Wyoming Territory. The Territory had given women the vote in 1869, the first state or territory to permanently do so. He printed the Governor’s reply in the July 11 Commercial.

Dear Sir.

In regard to your enquiries as to the success of woman suffrage in this Territory, its influence upon the women, the men, whether good or bad, its effect upon the body politic, I would respond affirmatively in every way. I send you a copy of my message of last November as an expression of my views. Michigan, rich in every element – material, intellectual, and moral – that goes to make up a State, with her famous University and no less famous Common School system needs this beneficent reform superadded, to constitute her a truly republican commonwealth and the model State of the Union. Wyoming has taken the lead of the Territories in adopting this reform. We trust that Michigan will pioneer her sister States.

Yours very truly,

J. A. Campbell.

The 1874 Michigan vote for the suffrage amendment was defeated, by 135,957 to 40,077. It wouldn’t be until 1918 that Michigan male voters voted to approve women’s suffrage.

Pattison did not live to see that vote – he died in Florida in 1908. But it’s likely his efforts, in his day, played a part in helping to eventually bring about equal voting rights for women.

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

Last week cmadler correctly guessed the symbolism of one Highland cemetery gravestone’s scroll, hand, and arrow. “The arrow denotes mortality. The scroll is a symbol of life and time, and can also suggest honor and commemoration. The hand is again upward-pointing, referring to ascension to heaven after death.”

This week’s Mystery Artifact is a strange, flimsy-looking device from the 1902 Sears Catalog. What might it be? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales of the Ypsilanti Archives,” available on Amazon, in Ann Arbor at Nicola’s Books, and in Ypsilanti at Cross Street Books, the Rocket, and Mix boutique. Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

Aha — I would guess that this artifact is a child seat for a bicycle that mounts on the handlebars — that’s what it looks like anyway.

Interesting guess Ms. B. I like your new avatar btw.

And it looks like a complete death trap! When I was a child, I rode in a baby seat that simply slipped over the front bench seat in the car on two bent (and unattached) aluminum poles. That was in the days before safety restraints of any kind. But at least there was a strap to keep me from sliding right out the bottom! The one I used to transport my daughter on the bike didn’t look much safer than this one — ack! Thank goodness she survived! (Glad you like my jay!)

I was reading a discussion the other day about how “suffragette” was considered derogatory and the women preferred “suffragist.” Any thoughts based on your research?

As far as the mystery object: my first thought was along the lines of a hydraulic/lifting chair at the dentist or barber. But it does also seem to evoke handlebars, especially since I can’t tell whether or not the bit under the “seat” is symmetric. And then I saw this pet high chair at Hammacher Schlemmer: [link]

so maybe it was a bike basket for animals? Kind of like Dorothy used to transport Toto?

Thanks to Laura Bien for the very intriguing article about local male suffrage advocates in the late 19th century. Thanks,too, for the shout-out about the upcoming exhibit, “Liberty Awakes: Winning the Vote for Women in Washtenaw,” scheduled for January and February, 2011 at the Museum on Main Street.

Regarding the very good question about the uses and abuses of the terms suffragette and suffragist…It is, indeed, the case that the term suffragette was controversial. Generally, it was the name given to supporters of Emmeline Pankhurst, the most well-known leader of the British suffrage movement. The term became even more charged after factions in the British suffrage movement, Mrs. Pankhurst’s among them, decided to use more militant tactics in their long campaign to secure the right to vote for women.

To draw on the British connection and the authorities’ response to suffrage militancy, I always think about the London, characters and songs from the iconic film, “Mary Poppins.” The children’s mother is a suffragette, and returns home from a Votes for Women rally. One of the lines from the “Sister Suffragette” song is, “Take heart for Mrs. Pankhurst, who has been clamped in irons again!” It is a reference to the arrests and jail time faced by many suffragettes.

Many suffrage supporters, particularly in the United States, did not want to be associated with the suffragettes’ militant actions and tactics to gain favor for the votes for women cause. For this reason, they termed themselves suffragists.

So, that, within the suffrage movement itself, to call oneself a suffragette was to identify with the more militant supporters. Many American suffrage advocates were quite willing to do so. The most famous, Alice Paul, founder of the National Woman’s Party, was also America’s most famous suffragette.

That it took over 70 years in America to pass what became the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote is revealing. To me, it means that whether many people called supporters suffragettes or suffragists, they did not think women capable of exercising a fundamental liberty essential to calling the place where one lives, a democracy.

Tricia: Thank you for your good question; Jeanine has provided a wonderful answer, I see: thank you, Jeanine!

My favorite story gleaned from researching this story was that 3 women in Massachusetts (?) from this era lost their property when they refused to pay taxes, claiming it unconstitutional to be taxed without representation.