In The Archives: The Farmer and the Poet

Editor’s note: In today’s world of Facebook Friends, we befriend folks with a click of a button. We can be “friends” with just about anyone: Ashton Kutcher or Bruce Springsteen or Barack Obama. These are, of course, at best “friendships at a distance.” This week, local history columnist Laura Bien takes a look at the way similar friendships were claimed in a past era. It was a time when a farmer – who was also a poet – could write a letter to his favorite poet and hope to receive a hand-written reply. Even if it was a “friendship at a distance,” the imprint of a human hand seems more authentic than the click of a mouse.

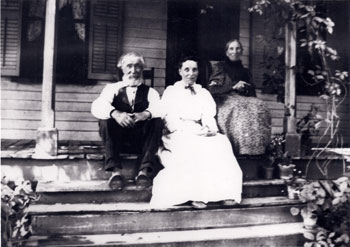

Well-remembered are Robert Frost’s three sojourns to the University of Michigan in the 1920s, and his house on Pontiac Trail, now at the Henry Ford Museum. Forgotten are the works of Ypsilanti poet-farmer William Lambie.

Lambie belonged to a generation earlier than Frost, but like Frost, Lambie had Scottish blood and took as his subject the natural world. Unlike Frost, he never left the occupation of farming or made much money. Lambie never won anything more for his verses than friends’ approval, with one exception – a penny postcard that Lambie valued as priceless.

The postcard came from another poet whom Lambie admired.

Lambie emigrated to the U.S. in 1839 at age 18 with his parents and eight siblings from the Scottish village of Strathavan just southeast of Glasgow. The family settled in Detroit, then purchased a farm in Superior Township just north of Highland Cemetery.

“We bought the Moon farm, in the town of Superior, in June, 1839, and had a fair, square battle with privations, exile and penury for many a day,” wrote Lambie in an essay – he read aloud from it years later at a Pioneer Society of Michigan meeting. “It was the half-way house between Sheldon’s and Ann Arbor, and had a bar for the sale of whisky. Kilpatrick, the pioneer auctioneer, said we could make more money on the whisky than on the farm, but we preferred the plow to the whisky barrel.” The family purchased 150 sheep.

Lambie’s father soon tired of America and in 1854 emigrated again to Ontario with his wife and younger children. Other siblings settled in Detroit. Only Lambie’s brother Robert stayed in Ypsilanti, where he worked as a tailor and later opened a clothing store and then a dry goods store. Robert also served on the city’s first city council in 1858.

William remained on the old Moon farm. Anna, the first of his six children, was born in 1851 when William was 30. In his diary entry for December 13, 1886, Lambie wrote, “Anna’s Birthday – It was a cold dreary day when she was born when we only had one wee stove and one room 12 by 16 and our few potatoes all froze – poverty within desolation.” William and his wife Mary wallpapered the inside of the house with newspapers in an effort to save the houseplants, but the plants froze.

William eventually built a larger house elsewhere on the farm and planted a grove of oak and apple trees nearby. By 1860 at age 39, he had five children ranging in age from 2 to 9 and a farm whose value adjusted for inflation – in an era of cheap land – was $94,000, a bit better than many of his neighbors.

On his 80 acres he raised oats, beans, wheat, barley, corn, and chickens and sheep. He also produced poems. In a May 15, 1876 diary entry he wrote, “A sick sheep drowned – pulling the dirty wool off a dead sheep is not very conducive to poetry.”

After William’s failed attempts to have a poem published in Harper’s, local newspapers began publishing his works. “My poem Auld Lang-Syne in the Commercial,” he wrote in his diary on May 26, 1877. This was a reworking of the familiar lyrics. William called it “A New Version of Lang-Syne.” His introduction to the poem reads, “It is a great pity that ever the world-renowned song of ‘Auld Lang-Syne’ should become the song of the drunkard, to lead either drunken or sober men farther away from temperance and virtue, and down the shameful road of disgrace and ruin. If this new song of Lang-Syne is not as good poetry as the old one, it at least inculcates better morality.”

The original song, of course, had been partially collected and partially composed by Robert Burns. Burns’ January 25 birthday was one of two annual events Lambie faithfully noted in his diary every year. Yet the “Ploughman Poet,” the “Bard of Ayrshire,” was not Lambie’s favorite poet.

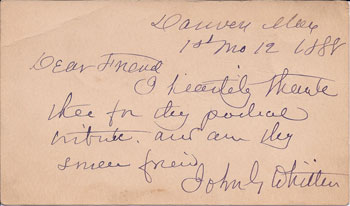

On February 1, 1886, Lambie wrote in his diary, “[daughter Isabelle] and I drove up with old Frank the horse, to her School. Good sleighing – Had a note from my favorite Poet Whittier.” John Greenleaf Whittier’s note was published in the Ypsilantian, in an edition unfortunately not locally available on microfilm. It was one of two artifacts Lambie would receive from Whittier.

The Presbyterian Lambie shared several values with the outspoken abolitionist Quaker poet, such as pacifism. In Lambie’s essay “Out in the Harvest Field,” from his 1883 collection of prose and poetry “Life on the Farm,” he wrote, “We detest all kinds of war and battle and murder, and believe it is far more manly and heroic to fill a man’s sack with corn than it is to kill him in battle.”

Lambie was also sympathetic to the spirit of abolition. The other annual event he always noted in his diary was Emancipation Day on August 1, commemorating Britain’s 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, which a year later ended slavery in most of the British empire. It was an antebellum holiday that was observed locally in Washtenaw County, Detroit, and Ontario – Canada was one of the British possessions affected by the Act.

In 1876 William attended the Aug. 1 Emancipation Day celebration in Ypsilanti. In his diary he wrote, “Ground very dry – hoping for rain – the colored man’s day of Freedom – [Isabelle] and I went to see the Celebration in William Cross Grove at the Fair Grounds [now Recreation Park] – The dark Beauties rigged out in white, red and blue and a feast of good things. Apples 75¢ a bushel.”

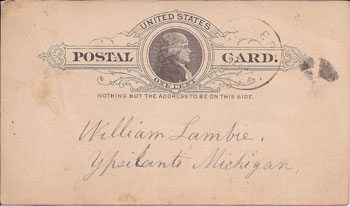

In December of 1887, at age 66, Lambie wrote a poem to Whittier in honor of the poet’s 80th birthday. He enclosed a prepaid penny postcard. The return address, “William Lambie/Ypsilanti, Michigan,” is written in Lambie’s plain yet graceful hand.

On January 17 of 1888, Lambie wrote in his diary, “Received a kind complimentary postcard from my favorite poet, Dear delightful John Greenleaf Whittier.” Written in a rapid, looping script, the postcard reads, “Dear Friend, I heartily thank thee for thy poetical tribute and am thy sincere friend. John G Whittier.”

Lambie saved this card and passed it down through family members. More than a century after Lambie’s 1900 death and burial in Highland Cemetery, the tiny and delicate card continues to be cared for today. The fragile relic speaks to the heart of a down-to-earth Ypsilantian farmer who never pretended he was otherwise – and yet befriended one of the nation’s leading poets.

. . . When winter days grow dark and dreary

And I am sad, and weak, and weary,

His pure sweet lines oft make me cheery.

Even Milton in his strains sublime.

And Burn’s in my land of Lang-syne

Are not read so well by me and mine . . .

—“Whittier,” William Lambie

-

Mystery Artifact

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

Guesses of last column’s Mystery Artifact ranged from earplugs to plumb-bobs. The two objects are copies of a set of acorn-shaped knitting-needle securers in the Ypsilanti Historical Museum. The needles fit snugly into the hole in the stem of the acorn, securing the work from sliding off the needles due to something like kitten mischief, until the knitter can return. Modern-day versions available at fabric stores are made of plastic and resemble tiny traffic cones.

This column we’re going from tiny to huge. This enormous artifact was made in Detroit and I can assure you it weighs quite a bit! But what might it be? Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Have an idea for a column? Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

I really have no idea but I want to guess. It looks like some kind of scale. It appears that what you are weighing, say for example marshmallows, can be placed on the platform on the right and then there is a slotted window where you read the weight. The window is slotted because there are conversions displayed in the window into other units as you read across. You can then determine how many tons, kips, pounds, ounces, drams and /or grains of marshmallows you have.

From here you would move on to your personal, tabletop, marshmallow cooker. (I know you made that up.)

I thought the knitting things were corn-on-the-cob holders.

abc: That is an interesting guess; we shall see. And the knitting protectors look very much like “corn people,” as we call ‘em in our house (the two little prongs look like legs…or something).

Oh no sir/ma’am, hand on heart here, I did not make up the tabletop marshmallow cooker; ’tis a real thing! Reality is plenty strange enough that there is an inexhaustible well of bizarre Mystery Artifacts!

In the spirit of exceedingly silly guesses, I will say that the metal canister on the left is a welding mask for a hammerhead shark. Or maybe the part on the right is a foot pump to pressurize air into the canister. Why pressurize air, you ask? Why not!

cmadler: “a welding mask for a hammerhead shark”–wow, there is poetry down here in the comments, too! I love that! Why pressurize air? Well, because then you have *more air* in the same container! More air than the next guy, anyways.

I concur with the notion of a scale. There appears to be a window on one side for the clerk and another (smaller) one for the customer opposite. It would also seem from the photo that the right side of the platen is worn to a lighter color by the butcher’s thumb.

Interesting guess, Cosmonican. Also an interesting observation about the platen; this artifact has not yet been cleaned; this is its original condition when acquired.

I think this is a roller from the press at the old Ann Arbor News Building.

I really did conclude this before reading @6. Am I still eligible for a prize?

John Floyd

Recent Republican for Council

5th Ward

Dear Mr. Floyd: Would you believe that my father, a former Heidelberg printing press mechanic, has an old roller-platen press in his garage? Weighs about a million pounds, is pretty much useless, and is the single, wonderful, thing I hope to inherit.

Of course, you are *eligible* for a prize, but so are we all. :)

I enjoyed the article on the poetic farmer, Laura. There is a bit of poetry in all of us but most refuse to let it out.

As for the artifact, I would guess it is some kind of container for liquid with one scale indicating how much water it started with and the second indicating how much completed product it has produced. Kind of like a coffee pot converting pure water to black coffee. Or possibly corn mash to whiskey? The only use I can think ofo for the object at the right is some kind of hot pad for the thing to sit on while performing its transformations.

Al: Thank you for your nice comment. I really grew to like William the more I researched him. It wasn’t all roses though; there are many difficulties involving his father’s inheritance and his sons that are in the diaries but which I just couldn’t fit into this article. At any rate, interesting M. A. guess!; we shall see. :)