Column: Tax Capture Is a Varsity Sport

On July 7, 2011 at the Michigan League on the University of Michigan campus, representatives of “The Varsity at Ann Arbor” hosted a gathering of citizens to introduce them to the planned 13-story building. The project is proposed for Washington Street, between the 411 Lofts building and the First Baptist Church, and will be purpose-built to house 418 students in 173 rental units.

When you drop the ball, even if it's shaped more like a rugby ball than a football, you still have a chance to recover the fumble.

To me, the highlight of that meeting had nothing to do with the site plan or the building design – which has evolved somewhat since The Varsity’s review on June 22 by the city’s newly created design review board.

Instead, I think the most exciting play of the citizen participation game was a kind of Hail Mary forward pass flung down the field by John Floyd, a former candidate for city council. The ball was snagged out of the air, just before it hit the turf, by Tom Heywood, executive director of the State Street Area Association.

I don’t think Floyd and Heywood play for the same team – nobody was wearing numbered jerseys at the meeting – so that might count as an interception, not a completed forward pass.

Floyd’s Hail Mary was this question: What is the benefit to Ann Arbor’s bottom line, if the new taxable value from The Varsity is subject to “capture” through the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority’s TIF district?

Heywood then provided a description of how the TIF (tax increment finance) works: the DDA capture is only on the initial increment – the difference between the property’s initial value, and the value after a site is developed – not on its later appreciation. What made it highlight reel material was the run-after-the-catch: Heywood went on to describe how a recently-discovered stipulation in the city’s DDA ordinance (Chapter 7) actually limits the amount of taxes the DDA captures.

Heywood’s explanation of how the limit works was accurate, based on the interpretation of Chapter 7 that has been used by the DDA and accepted by the city of Ann Arbor. That interpretation – a year-to-year calculation of excess tax capture – resulted in a repayment earlier this year of roughly $473,000 from the DDA to the Ann Arbor District Library, the Washtenaw Community College, and Washtenaw County for excess taxes that the DDA had collected. The city of Ann Arbor chose to waive its $712,000 share of the calculated excess.

On the year-to-year interpretation of excess, Heywood was correct when he said that the DDA’s capture depends in part on which projects are added to the tax rolls in a given year. If new projects are spread over multiple years, the Chapter 7 limit does not have as great an impact as it would if they are all completed in a given year.

The tax capture issue, of course, is not within the control of The Varsity’s developer. Its discussion at the citizen participation meeting might be fairly characterized as playing football on a baseball field. I think the response of The Varsity’s development team to the tax issue was the right call: They said they’ll pay the tax bill, and if you’re not happy with the way that taxes are captured and distributed, then you should take it up with your local elected officials.

So after writing a column over a month ago, before that meeting – “Taxing Math Needs a Closer Look” – I’m taking it up, again, with Chronicle readers and my elected officials.

The year-to-year approach to the calculations is, I think, simply not defensible as correct, based on the language of the Chapter 7 ordinance. I think the correct way to calculate excess is based on comparing the total valuation in the district against the forecasted valuation – a cumulative method.

It turns out that I think I dropped the ball on one of the calculations in that previous column. But even factoring in a revised formula, the amount of excess taxes captured in the DDA district since 2003 appears to be around $2 million, instead of the roughly $1.2 million that the DDA and the city of Ann Arbor calculated as the excess.

In this column, I want to discuss briefly the corrected formula. It’s a way to remind elected officials of other taxing authorities – the library board, the county’s board of commissioners, and the community college’s board of trustees – that a significant number of tax dollars are in play for them, not just now, but into the future.

Hurry-Up Offense Style Review

For more detail and historical background, I’d invite readers to begin with the column from early June: “Taxing Math Needs a Closer Look.” Here, I just want to provide enough of an overview to make a revised formula from that column understandable.

Review: Chapter 7

Chapter 7 of Ann Arbor’s city code lays out how the tax capture of the Ann Arbor DDA is limited, or capped. The mechanism used to cap the amount of captured tax is the projected value of the increment in the TIF district, as laid out in the DDA TIF plan. The TIF plan is a required document under the state enabling legislation for DDAs (Act 197 of 1975). From Chapter 7 [emphasis and extra emphasis added]:

If the captured assessed valuation derived from new construction, and increase in value of property newly constructed or existing property improved subsequent thereto, grows at a rate faster than that anticipated in the tax increment plan, at least 50% of such additional amounts shall be divided among the taxing units in relation to their proportion of the current tax levies. If the captured assessed valuation derived from new construction grows at a rate of over twice that anticipated in the plan, all of such excess amounts over twice that anticipated shall be divided among the taxing units. Only after approval of the governmental units may these restrictions be removed. [.pdf of Ann Arbor city ordinance establishing the DDA]

Historically, the Chapter 7 provision has not been applied. But it was noticed this year by city of Ann Arbor financial staff and brought to the DDA’s attention. The result was a repayment of roughly $473,000 from the DDA to the Ann Arbor District Library, the Washtenaw Community College and Washtenaw County. The city of Ann Arbor chose to waive its $712,000 share of the calculated excess.

One major issue is how to understand “growth” as specified in Chapter 7. The city of Ann Arbor and the DDA have used a year-to-year method of defining excess. I think that’s not correct. Instead, I think that the correct way is to use a cumulative method.

Review: Year-to-Year versus Cumulative Approach

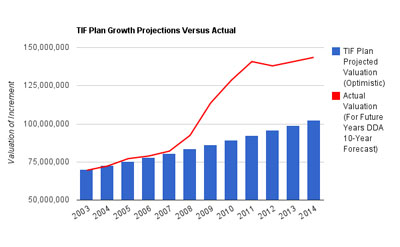

In Chart C, the blue bars represent the forecasted valuation of the tax increment on which the DDA tax capture will be based. (The forecasted valuation is included in the DDA TIF plan.) The red line reflects the actual valuation of the tax increment in the district. For future years, the red line reflects the DDA’s current 10-year budget planning document.

Chart C. Blue bars are the forecast valuation in the Ann Arbor DDA's TIF plan. The red line is the actual valuation. For years 2013 and 2014, the DDA's 10-year plan is used. (Links to larger image.)

The easiest way to see the difference between the year-to-year method and the cumulative method is in year 2012. The actual valuation (red line) in 2012 drops compared to 2011. So on the year-to-year method, there can be no excess for that year – no matter what the forecast (blue bars) is. That outcome arises because the year-to-year method incorrectly re-sets the benchmark for calculating the growth rate to the immediately previous year.

The cumulative method, on the other hand, would determine that there is an excess for 2012. Even though the valuation dips from 2011 to 2012, the red line is still clearly higher than the blue bars.

This also highlights the fact that the year-to-year method does not impose an actual cap on the total TIF capture by the DDA for the period of the DDA’s existence. It only imposes a cap on the capture in any given year – which is defined relative to just the preceding year.

If the valuation of the increment spikes in the district, then in the first year of the spike, the year-to-year method calculates an excess valuation due to that spike. But after that spike levels off, the year-to-year method determines there is no excess. And even if an upward growth trend continues, the year-to-year method does not carry forward the excess from previous years in the same way that the cumulative method does.

So Tom Heywood’s comments at the citizen participation meeting for The Varsity were an accurate depiction of the way the city and the DDA have chosen to interpret Chapter 7 – on that interpretation, the timing of new development is significant.

Doubling the Score

If the cumulative interpretation of the Chapter 7 language is correct – and I think it is – then we still have to make a specific interpretation of the part of the ordinance that reads: “If the captured assessed valuation derived from new construction grows at a rate of over twice that anticipated in the plan, …”

It’s especially important because if the condition set forth in the if-statement is satisfied, the consequence is that all of that excess – not just 50% of it – must be divided among the other taxing authorities instead of being captured by the DDA.

I think if we adopt the cumulative interpretation of the ordinance, then the “twice that” clause can be paraphrased as follows: “If the actual valuation in the district is more than twice what the valuation was forecast by the TIF plan to be …”

In Chart C, that means: “If the red line is twice as high as the blue bars.” In spreadsheet terms (link are below), that’s “If Column C is more than twice as much as G …”

The point is, the condition has not yet been met that would trigger the “twice that” clause in the ordinance. But on the formula I used in the previous column to calculate excess, the “twice that” clause was triggered, and had an impact on the calculations. Replacing the formula with the correct one shows a less dire, but still significant impact.

On the original calculations in the previous column, the total amount of excess taxes that had been captured since 2003 worked out to roughly $3 million – as contrasted with the roughly $1.2 that the city and the DDA calculated. The revised calculation, with a correct implementation of the “twice that” clause, works out to $2.05 million. Even if the city of Ann Arbor were to waive its share, that would still work out to an additional $400,000 to be returned to other taxing authorities in the short term: Google spreadsheet: Cumulative Realistic (Revised)

More significant than the short-term picture is the roughly $600,000 a year that would in the future be divided among other taxing authorities instead of being captured in the DDA district. The city of Ann Arbor’s share of that is roughly 60%, or $360,000. Measured in numbers of city staff – whether they’re police officers or planning specialists or field services employees – that works out to almost four full-time employees.

Playing on the Varsity Squad

So what’s the actual answer to John Floyd’s question about possible benefit to the average citizen from The Varsity at Ann Arbor? Well, the current total valuation of the increment in the DDA district is far greater than the forecast in the DDA TIF plan. So a correctly interpreted Chapter 7 would ensure that future projects would effectively add at least half their valuation to the city’s tax base. That means at least half of the taxable value added by The Varsity to the city’s base would effectively be taxed by the city of Ann Arbor – just as properties outside the DDA district are taxed.

A correctly interpreted Chapter 7 would mean that Floyd’s standard critique of new downtown development – that it doesn’t add directly to the city’s general fund – is only half right. A correctly interpreted Chapter 7 would help make a case for increased development in the downtown area – half the added value of that development would go to the taxing authorities that levy taxes, instead of to the DDA.

In the nearly three years that I’ve covered the DDA for The Chronicle, I’ve developed some expectations of how its board and staff might handle certain situations based on past performance. When the Chapter 7 issue was raised by the city of Ann Arbor’s financial staff earlier this year, the DDA handled the calculation of excess in a way that was counter to my expectation, based on past observation.

It was like watching former Michigan football QB Tom Brady taking a snap from center and then tripping over his own feet as he dropped back to pass, then fumbling the ball. But Tom Brady wouldn’t just lie there on the ground and cry like some kind of scrimmage-squad Rudy. He’d scramble after that ball. And that’s what I think the DDA will do now.

It’s certainly what the DDA and the city of Ann Arbor need to do now – recover their own fumble. It’s the difference between playing for the scrimmage squad and playing for the varsity. It means acknowledging the correct way to calculate past excess TIF capture, making other taxing authorities whole, and making clear that the excess will be calculated correctly in the future.

If they don’t do that, a loose ball will still be bouncing around on the field. It could become a political football – and someone else might pick it up and run for a touchdown.

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public bodies like the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority and the city of Ann Arbor. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

Who knew what a wonk was at the other end of the totter? (This would be a good subject for a tottertoon.)

Thank you for all this great exposition. I know I’ll find it really valuable once I get past the sports analogies. I’m nearly illiterate in that regard though I do know that we want a level playing field for the citizens of the town.

Whether related or not – I note that three (revised?) DDA annual reports are on the agenda to Council tonight.

Dave,

There must be a better way to get Brady Hoke on the Totter. This sort of sucking up really does not become you.

I’m still a tad fuzzy on the “PROJECTED TIFF Capture” idea. I’ll have to re-read your work.

I have several objections to “Tax Capture (theft, really)”, as well as to the existence of the DDA as an entity apart from city government. We can talk about them some other time.

Does this same sort of limitation cover the Local Development Finance Authority (the tax-capture entity, co-terminus with the DDA zone, that funds Ann Arbor Spark with public education money)?

Re: [2] Does this same sort of limitation cover the Local Development Finance Authority (the tax-capture entity, co-terminus with the DDA zone, that funds Ann Arbor Spark with public education money)?

The kind of limit on TIF capture expressed in the DDA ordinance is, I’m pretty sure, peculiar to the Ann Arbor DDA. I can’t find anything in the LDFA foundational arguments expressing a limit that is triggered when actual tax valuation exceeds projected values. However, it’s worth noting that the LDFA’s tax capture is simply defined at 50% [emphasis added]:

That part is emphasized, because even though Ypsilanti does not generate any revenue for the LDFA, the Ypsilanti city council still appoints three seats to the LDFA board. Why? I don’t know. It was set up that way.

Also related to the question of who gets a seat at the table is the fact that Skip Simms, an employee of the LDFA’s main contractor (Ann Arbor SPARK), also sits on the LDFA board – as a non-voting ex officio member. He was appointed to that position a couple years ago. [cf. Chronicle coverage: "Expanded LDFA Board Reflects on Purpose"] Even as a non-voting member, that’s pretty odd, I think. It would be similar to appointing Mark Lyons, manager of Republic Parking, to an ex officio seat at the DDA board table. Yet, the LDFA was set up that way. It’s a part of the agreement between Ypsilanti and the city of Ann Arbor on the LDFA that a representative of the “accelerator” (i.e., Ann Arbor SPARK) will have an ex officio seat on the LDFA board.

The Ann Arbor city council appointment to the LDFA board actually received some discussion at Monday’s July 18 council meeting – Stephen Rapundalo’s continued appointment was for another four years, despite the fact that he might not be re-elected. That’s because the terms for such appointments as expressed in the LDFA bylaws are only for four years. Based on the brief council discussion, it appears that a bylaws change to address that is on the horizon.

Part of the reason there is not more outcry about the LDFA’s capture of local education tax dollars is due to the way that local education is funded in the state of Michigan – local taxes are forwarded to the state, which then re-allocates the money to the individual school districts on a per pupil basis. So there’s no direct negative impact to Ann Arbor’s local schools – it’s a negative impact spread out over all schools statewide, which elected officials who voted for this judged to be a minimal amount. From the LDFA TIF agreement:

The LDFA’s relationship to Ann Arbor SPARK is roughly parallel to the DDA’s relationship to Republic Parking. In both cases, the TIF authority contracts with its vendor to provide services. The services Ann Arbor SPARK provides to the LDFA are for a “business accelerator” as specified in the SMART ZONE legislation that was enacted in the early 2000s, which allowed the creation of Ann Arbor’s LDFA. Just like Republic Parking, Ann Arbor SPARK is supposed to have an existence and a mission independent of its contract with the LDFA. That mission independent of the business accelerator (which takes the form of three separate incubators operated by SPARK) is what the city of Ann Arbor has supported with an additional annual general fund contribution to SPARK of $75,000.

So to continue with the football analogy, let’s imagine that the way the LDFA is set up and the way it interacts with SPARK is a football game. Some objections fall into the category of “I think football is a dangerous/stupid sport; let’s not play it.” For example, John, I think your basic philosophical objection to TIF as an approach to finance falls into that category.

But there are other objections that fall more into the category of “We need a better helmet-to-helmet contact rule.” Those are objections that I think have at least some small short-term chance of getting some action. For example, I think it’s reasonable to separate off Ypsilanti representation on the board to ex officio status until such time that there are actually tax dollars generated from the Ypsilanti district. I also think it’s reasonable to change the Ann Arbor-Ypsilanti agreement to stipulate that a representative of an LDFA contractor should not have any seat on the board (ex officio or not). I also think it’s reasonable to require that the LDFA hold its meetings at some location other than its main contractor’s (Ann Arbor SPARK’s) offices.

I also think that it would be worth reflecting on the fact that making cash payments for the operation of a business accelerator is one of myriad possible uses of LDFA monies. Another specified use in the foundational documents relates to investments in actual physical infrastructure. What kind of physical infrastructure? One example would be a high-capacity fiber-based communications network. Sound familiar? That’s what we in Ann Arbor were hoping that Google would build for us. At the time of the all the energy and excitement about that (March 2010), Wes Vivian addressed city councilmembers and told them that if Google doesn’t build that network, then the city needs to figure out a way to make it happen independently of Google. At a city council work session around that same time period, Sandi Smith (Ward 1) confirmed with Stephen Rapundalo (Ward 2) – the city council’s representative to the LDFA – that building a fiber communications network was one possible use of LDFA money.

A fiber network is at least something that in 2018, maybe the LDFA board could point to as “That’s what we built, you’re welcome.” That would stand in contrast to claims about “number of jobs created,” for which there doesn’t seem to be standard way to count. Why 2018? The LDFA is supposed to have a lifespan of 15 years, starting in 2003 – unless it is renewed.

This just in from the DDA board: SPECIAL BOARD MEETING WEDNESDAY, JULY 27, 2011 at 10:00 AM (TO DISCUSS TIF FUNDS)

Thanks for the exposition on the LDFA. The reason Ypsilanti was excluded may have had to do with county politics. The LDFA was originally set up as a SmartZone under an initiative by the MEDC. As the county resolution explains [link], it was necessary to include Ypsilanti as part of the SmartZone because of state law regarding multi-community zones. I suspect that there was negotiation that Ypsilanti should not have to pay taxes since it has often been seen as a distressed community.

The SmartZone succeeded the IT Zone (founded 1999). Here’s what Crain’s said about it: “A group of University of Michigan professors who wanted to wire downtown Ann Arbor with higher-bandwidth Internet connections founded the Ann Arbor IT Zone in October 1999″. From the county resolution, “The purpose of the SmartZone is to support small, start-up technology

companies, primarily in the information technology field within the Zone.” Later Washtenaw Development Corporation merged with it to form SPARK, which has taken on a much more diffuse mission.

Dave,

Another thorough treatment of an arcane, yet vital, public process.

By the way, you may add to your list of “John Floyd’s Philosophic Objections”, the use of public school taxes for any purpose other than – public schools. If Ann Arbor Spark is really worth funding, let them get their own tax from the voters. Passing taxes under the guise of one use (k-12 education), and then putting those taxes to use for an utterly unrelated activity (Ann Arbor Spark), is another manifestation of the rot in our political culture.

Many political actors in Michigan view the School Aid Fund (including local operating millages) as a slush fund to be raided for whatever thing they cannot otherwise fund. The BEST that can said about this practice is that it amounts to eating our seed corn. It is something of an irony that our technology-business accelerator is funded at the expense of the next generation’s ability start tech companies.

I’m a newbie to this site and definitely not familiar with the intricacies of public financing (my eyes tend to glaze over 30 seconds into any discussion of economics), but TAXES LEVIED FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION ARE ACTUALLY DIVERTED TO OTHER GOVERNMENTAL (non-elected) ENTITIES???!!!