In the Archives: From Cordwood to Caviar

Editor’s note: Laura Bien’s In the Archives column for The Chronicle appears monthly. Look for it around the end of every month. Subsequent to the appearance of this article, Bien was interviewed by Interlochen Public Radio about Great Lakes sturgeon. Listen to the interview online via the Interlochen Public Radio website.

Twenty thousand dinosaurs live in the river system bordering Detroit. They’re rugged descendants of the few who survived one of Michigan’s worst ecological disasters, against which one University of Michigan professor battled – in vain. His efforts were crushed by Michigan’s short-lived yet feverish caviar industry.

The snaggletooth scutes along the lake sturgeon are visible on this depiction of the lake sturgeon (public-domain image).

Among the most primitive of fish, sturgeon first appeared when the Earth had just one continent. Millenia later the lake sturgeon thickly populated the Great Lakes and was fished by native peoples.

A young adventurer of noble French birth described the fish in his 1703 bestseller whose English title is “New Voyages to North America.” Baron de Lahontan’s book detailed the experiences gleaned from a decade of travel in New France, the onetime colony that encompassed most of present-day eastern Canada and the U.S. He wrote of Lake Erie, “[I]t abounds with sturgeon and whitefish, but trout are very scarce in it as well as the other fish that we take in the Lakes of Hurons and [Michigan].”

Sturgeon remained common over a century later, as noted by James Lanman in his 1839 book “History of Michigan.”

These lakes abound also with fish, some of the most delicious kinds. Among these are the Sturgeon, the Mackinaw Trout, the Mosquenonge [muskellunge], the white fish, and others of smaller size peculiar to fresh water. The Sturgeon advances up the stream from the lakes during the early part of spring to spawn, and are caught there in large quantities by the Indians.

In the first half of the 19th century, Michigan settlers were beginning to catch sturgeon too, to their irritation. In trying to net the prized whitefish, fishermen in lakes Michigan, Erie, and Ontario viewed sturgeon as unwelcome bycatch, too fatty and rank to eat. Six to nine feet long or longer, the fish bore five rows of pointed scutes, or toothlike scales along its body that ripped holes in fishing nets. Fishermen killed sturgeon and dumped or buried their carcasses on shore. In Ontario at Amherstburg, the oily fish were stacked like firewood and left to dry. The mummified bodies were burned to heat the boilers of wood-burning steamboats on the Detroit River.

Sturgeon as Bycatch

In 1873 the state took note of the rapidly-growing Michigan fishing industry as a whole and created the Michigan Fish Commission.

Its first president, 55-year-old New York-born George Jerome, had previously worked around the Midwest as a lawyer, real estate agent, newspaper editor, chairman of a state Republican committee, and tax assessor before building a comfortable home in Niles, Michigan. Jerome was a gentleman of “peculiar charm and magnetism of his individuality,” read one later remembrance. “He impressed everyone with his overflowing good humor and jollity, while his genial wit, fund of anecdote, and skill as a story teller, made him one of the most companionable of men.”

Jerome was also a man of action. Upon hearing that the creation of a state board of fish commissioners was pending, Jerome sped to Lansing to support the measure. His considerable efforts were rewarded with a position on the board. Soon after he became its superintendent.

Jerome wrote the Commission’s inaugural 1873-74 report. More literary than bureaucratic, the work championed artificial fish breeding. “It is as distinctively an art as is glass or iron manufacture,” he wrote, “ . . . [n]ot, perhaps, one of the ‘liberal’ or ‘fine’ arts, yet the century may not close ere the adjectives ‘liberal’ and ‘fine,’ shall not inaptly qualify our rising and cherished art.”

Jerome reflected that increasing demand in the 1870s was straining the Michigan fish supply. “Indeed, this is the fish problem,” wrote Jerome, “nothing more, nothing less. And to the solution of this problem, the veteran band of fish culturists, with the appliances at hand, and with a will and courage equal to every conceivable emergency, have gone to work, resolved not to lay down their tools till every promise of theirs is redeemed and every prophecy fulfilled.”

One goal of the “pisciculturist,” wrote Jerome, was to artificially breed valuable whitefish, trout, grayling and black bass, and stock them in waterways to replace fish he regarded as “too worthless to dwell on,” including suckers, catfish, and sturgeon. But the worth of the sturgeon was about to change.

Sturgeon Fortunes Change

In the 1860s it was found that smoking the fish reduced its oiliness and made it tasty. Often sold as halibut, smoked sturgeon became popular. Other sturgeon products emerged. The swim bladder was processed into isinglass, a gelatine used in applications that included beer-brewing. Sturgeon hide was made into leather. Sturgeon oil, refined, was sold to watchmakers and sewing-machine dealers. Sturgeon oil also found its way, according to a single secondary source, into many Michigan lighthouses, where it burned with a brighter, less smoky flame than the whale oil then in use.

A news tidbit in the April 19, 1887 Ypsilanti Commercial urged people to go and see the 150-pound sturgeons at Bradley's meat market.

Despite Jerome’s lofty aims, budget restraints, a lack of manpower, and a then-rudimentary grasp of fish ecology ensured that the Commission never kept pace with, much less regulated, the Michigan fish industry. Read as a whole, the late 19th-century Commission reports merely document, aside from some fish-stocking experiments, a growing disaster the bureau was helpless to prevent.

Perhaps Jerome foresaw this calamity. He retired after his first term, and the state promptly slashed the Commission’s budget from $7,000 to $5,000 [from $133,000 to $95,000 in today’s dollars].

Just a few years later, the 1877-78 Commission report warned, “there is one most alarming fact, that confronts us and must be confessed. It is this: these Great Lakes … the common food store-houses of the people, are being plundered, robbed, impoverished.”

The Caviar Threat

Around this time, an additional threat appeared. In the 1860s, the Schacht brothers in Sandusky had begun producing caviar from Lake Erie sturgeon. The profitable practice spread to Michigan, likely led by other immigrants from homelands with a tradition of caviar production.

S. Von Haller's ad in the March 1886 issue of the Normal News advertised smoked sturgeon. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Up to a third of an adult female sturgeon’s body weight can be roe – a harvest of 70 pounds from one fish was not uncommon. Formerly the roe from Michigan sturgeon was sold as cheap fish bait, hog slop, or soil fertilizer. In the mid-1880s the Michigan caviar industry exploded and prices began to soar. A 135-pound keg of caviar that cost $12 in 1885 [$287 today] climbed to $40 in 1894 [$1,000] and $100 in 1900 [$2,600].

Makers tried to keep their manufacturing process secret, though it was simple – the roe was gently rubbed through a screen to free it from surrounding membrane, then salted and packed. “[Local resident] Mr. Haas has a peculiar process for curing the caviar, which he keeps a secret” reported the Sept. 26, 1890 Benton Harbor Weekly Palladium, “and he seems to be making money …”

Newspapers in distant states took notice of Michigan caviar. “Among the many industries peculiar to Detroit,” read a Jan. 5, 1886 article in the New London, Connecticut newspaper The Day, “not the least important is the traffic in the sturgeon and its products. The sturgeon is the whale of the lakes, weighing ordinarily from 40 to 100 pounds, but often reaching 150 or more.”

There were now five factories in Detroit, said the article, devoted exclusively to smoking sturgeon filets, and several major Detroit fish dealers who made and exported caviar to Germany and Russia. One dealer said that his annual export was 60,000 pounds. A Detroit Free Press article said of sturgeon caught at the mouth of the Detroit river, “The caviar is sent to Berlin where it is sold at enormous prices to wealthy Germans … They say that the caviar from Detroit river sturgeons is the best and that it is reserved for the German nobility.”

Around the same time, the Galveston News published an article that suggests a Detroit caviar urban legend:

There is a Russian who keeps a hotel in Detroit, and he is fond of caviar. As he always insisted that the caviar sold there would not compare with what could be had in Russia, he finally wrote over to Russia and asked his friends to send him a can of the caviar that was most popular at that time in St. Petersburgh. After a long interval the caviar arrived. On taking off the wrappings he saw on the label of the can that it was put up by a canning company in Detroit, and was warranted to be made of the best roe of Lake St. Clair sturgeon.

Fisheries in other Great Lakes states were also rapidly producing caviar. “Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin rival all Muscovy and Scandinavia in the production of caviar, that for the most part is exported to Europe,” said an August 1886 Scientific American article.

Lower-grade caviar was consumed domestically, to the extent that the open-faced “caviar sandwich” became a standard item available at lunch counters, taverns, and train station restaurants. The December 1908 issue of “The Spatula,” a druggists’ magazine, suggested possible food items to druggists thinking of adding a soda fountain counter to their shop. They included a ham sandwich for 5 cents [$1.20], oyster stew for 20 cents [$4.80], a chicken salad sandwich for 20 cents, and a caviar sandwich for 20 cents.

The caviar sandwich even became a meme to describe the appearance of crowds. Ohio-born politician-author Edward Townsend in his circa 1895 short story “No One in Town” wrote, “The children there would astound you, my dear, by their number. They were spread over the sidewalk as thick as sturgeon eggs over a caviar sandwich.” Indiana-born Pulitzer prize-winning political cartoonist and author John McCutcheon in his 1920-1921 novel “The Restless Age” wrote of a crowded theater, “looks like a bird’s-eye view of a caviar sandwich. If they expect to crowd any more in here they’ll have to let out a tuck in the opera-house.”

Demand was causing a crisis. The Michigan Fish Commission reported in 1888 that “in our own state today one of the most valuable of commercial fish is the worthless sturgeon of a few years ago, and so assiduously is it sought for that the supply will become exhausted in a very short time unless the fish-culturist comes to the rescue.”

Scientific Response

It was too severe a crisis, however, to be solved with a few bottles of fertilized eggs. Missing and desperately needed was a better, more holistic understanding of aquatic ecology. Professor Jacob Reighard helped the University of Michigan become one of two leading universities pioneering this emerging science.

Reighard initially worked with the Fish Commission at a small makeshift laboratory near New Baltimore on Lake St. Clair, studying whitefish and sturgeon. “Concerning even the most important of the food fishes of the Great Lakes our knowledge is very meager,” Reighard wrote. “[W]e do not know enough of the spawning habits and spawning places of the sturgeon of the Great Lakes to be able to procure the eggs for artificial propagation. The sturgeon is rapidly disappearing.”

Reighard did not know that sturgeon are extraordinarily long-lived and late to mature sexually. Males can live for 55 years, with females living 80 to 150 years. Females do not usually become sexually mature until they are in their mid-20s. Once sexually mature, both sexes are fertile only once every few years afterwards. As a result, during any given spawning season, only 10 to 20 per cent of the entire adult population is sexually active, one reason why sturgeon numbers fell so quickly once intensive fishing began.

Reighard needed a better research station. He was instrumental in the creation of a permanent research facility, UM’s present-day Biological Station on Douglas Lake in Cheboygan County. Reighard became, and remains, nationally known for his insights and work regarding aquatic ecology.

Tragically, by the time the Biological Station was built in 1909, Michigan sturgeon populations and the sturgeon industry had largely collapsed.

“Some years ago, sturgeon were abundant in the waters of our state,” noted the 1895-96 Michigan Fish Commission report, “but since 1891 the decrease in each year’s catch has been rapid, with slight hopes of their restoration . . . [i]n 1891 the sturgeon catch was 831,606 pounds, going down each subsequent year to 1897, amounting in that year to 184,881.” In an October 1908 Popular Science Monthly article titled “The Passing of the Sturgeon,” Walter Sheldon Tower wrote, “Lake St. Clair, which alone gave nearly a million pounds in 1880 has not produced more than 10,000 pounds in recent years, while the catch in Lakes Michigan and Erie has fallen to about one sixtieth of its former proportions.” By 1929, the state enforced a total ban on harvesting any sturgeon whatsoever, for fear of complete extinction.

However, you can fish for them today.

Sturgeon Today

Lake St. Clair and the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers are home to Michigan’s largest population of lake sturgeon. When recreational divers just a few years ago reported seeing sturgeon spawning under the Blue Water Bridge, the DNR investigated. Scattered anecdotal reports over the years of sturgeon sightings had been made, but no one dreamed that a large and breeding sturgeon population had been living in the water system for years.

Catch-and-release hook-and-line fishing with a sturgeon permit is legal in Michigan. Harvest is possible at only three Michigan locations: The St. Clair and Detroit river system, Otsego Lake in Otsego County, and Black Lake in Cheboygan County. Each place has its own specific season. Earlier this February, nearly 200 anglers gathered at Black Lake. Its season was only a few hours long, with a total harvest of only two fish allowed. The St. Clair harvest season is July 16 to September 30, and with a permit the annual limit per angler is one sturgeon.

Strict seasons and limits and tough penalties for poachers are not the only protectors of modern sturgeons. In the fall of 2010, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality water resources district supervisor and Grosse Pointe resident Andy Hartz helped found the St. Clair and Detroit River chapter of Sturgeons for Tomorrow. The non-profit conservation group is open to all, with a yearly membership fee of $20. It now has about 45 members, and helps fisheries managers in the ongoing rehabilitation of local lake sturgeon populations. Many members enjoy fishing for sturgeon, with the vast majority practicing catch-and-release.

“It’s such a neat fish,” says Hartz. “And they live for so long that it’s the only fish that three generations of a family can catch. You can catch it, and then years later your son can catch it – the same individual fish – and then your grandson can catch it.”

With luck and careful management, that will remain true as populations of the venerable sturgeon continue to recover from their indiscriminate exploitation over a century ago.

Grateful thanks to Andy Hartz for contemporary sturgeon population data.

Mystery Artifact

Last month’s column presented a new acquisition of the Ypsilanti Historical Museum.

As Irene Hieber, Eleanor Pollack, Jim Rees, TJ, and Bear all guessed, this is a dictation machine, made by the Edison company.

I was about to add that you could say it’s an early tape recorder before realizing that that comparison unfortunately dates me. A recording device, let’s say.

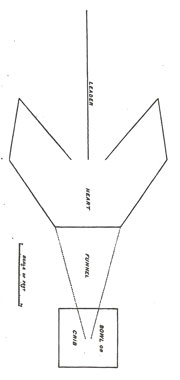

This column’s mystery artifact is a device in use in Michigan for much of the 19th century. Reviled by some and overused by others, it had a major impact.

What might it be?

Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and “Hidden History of Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our columnists like Laura Bien and other contributors. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

It is a high-tech, supersonic, swept-wing, marshmallow shooter. You take said devise and stick it into the marshmallow, or crib, as shown. Squeeze wings sharply. Marshmallow goes supersonic across the room.

ABC: That sounds vaguely like a spy’s disguised stealth weapon…perhaps if you crossed John LeCarre with Dr. Seuss. :) Thanks for reading!

I would surmise a type of fishing net is diagrammed here? A crib for the baby sturgeons.

Cosmonicon: Interesting guess…..it was very common, TOO common, in MI at one time.

Apropos of the article topic, it looks to me like a pound net, a type of fish trap.

cmadler: Intriguing speculations as always…thank you for reading!

Thanks for the article about the sturgeon. It made me remember a talk I heard from a Russian botanist. She showed slides of a plant collecting trip in the far west of what was the Soviet Union in which they camped out and pulled large female fish (I assume sturgeon) from the nearby water. The roe was removed and the fish left to rot.

I did a search after reading your article. American caviar is now collected from farmed sturgeon who mature much more quickly than in the wild. It appears that the female fish are still killed at harvest. This is called “sustainable” production. The roe are supposed to be aged before developing full flavor.

It is a diagram of a trolling net.

Before the fall of communism I once shared a Russian train compartment with a woman who was taking a bucket of caviar, probably about 10 Kg, to Warsaw where she was going to sell it for about $100. At that time it was selling in West Berlin for $1 per gram.

Vivienne: Interesting comment, thank you. There is actually one remaining caviar producer in MI, on the shores of Lake Michigan, but it appears that the company merely processes roe that they receive from other sources.

Dave: Hmm, we’ll see, thank you for reading!

Jim: What a fantastic story…I hope you have written it up for publication; I’d love to read it if so!

After publication of this column, Laura Bien was asked to talk about sturgeon by Interlochen Public Radio. Listen to the interview here: [link]

Hmmm… A lot fur trading went on in 19th Century Michigan. Is it some sort of Otter/Beaver/Mink trapping device?

Your clues: “too common” [and] “reviled by some, overused by others,” having a “major impact” leads me to think it was a harvesting tool of some sort. Maybe a massive lumber channelling device used to funnel millions of White Pine logs down Michigan waterways for loading onto the mighty freighters of our Great Lakes destined for use in construction on the more densely populated Eastern seaboard.

I know that the clear cutting methods of that era (prior to thought or principles of conservation or planned reforestation) more certainly left a tremendous impact on Michigan’s natural environment and the future industry of its people that is still being felt today.

Laura,

I have not written that one up but here’s another story you might like, about a different group of nomadic traders. [link]

Laura, thanks so much for bringing attention to the continuing existence of an important part of Michigan’s history. What a great job you’ve done in documenting the history. Why don’t you try publishing in Michigan History, to bring it to the attention of more Michiganders? You’ve done a superb job, thanks.

Jim: I do like that story; thank you for the link! That beer must have tasted awfully good.

Hi Mr. Wieland: thank you for your very kind comment and thanks for reading. Well, I had a story in MHM last year and there’s one slated for this summer (they restrict authors to 1 per year in order to get the maximum diversity of authors). They are really a great organization to work with, very skilled people.