Final Forum: What Sustains Community?

The fourth and final forum in a series on sustainability in Ann Arbor focused on community, touching on topics that contribute to a stronger social fabric – quality of life, public safety, housing, and parks.

Interim Ann Arbor police chief John Seto talks with Eunice Burns, a longtime activist who attended an April 12 sustainability forum at the Ann Arbor District Library. Seto was a panelist at the forum, which focused on building a sustainable community. (Photos by the writer.)

Community is one of four categories in a framework that’s been developed over the past year, with the intent of setting sustainability goals for the city. Other categories – which have been the focus of three previous forums this year – are resource management; land use and access; climate and energy; and community.

At the April 12 forum on community, Wendy Rampson – the city’s planning manager, who moderated the discussion – told the audience that 15 draft goals have been selected from more than 200 already found in existing city planning documents. The hope is to reach consensus on these sustainability goals, then present them to the city council as possible amendments to the city’s master plan. The goals are fairly general – if approved, they would be fleshed out with more detailed objectives and action items. [.pdf of draft sustainability goals]

Rampson said that although this would be the final forum in this year’s series, there seems to be interest in having an annual sustainability event – so this would likely not be the last gathering.

The forum was held at the Ann Arbor District Library’s downtown building, and attended by about 50 people. Panelists were Dick Norton, chair of the University of Michigan urban and regional planning program; Cheryl Elliott, president of the Ann Arbor Area Community Foundation; John Seto, Ann Arbor’s interim chief of police; Jennifer L. Hall, executive director of the Ann Arbor Housing Commission; Julie Grand, chair of the city’s park advisory commission; and Cheryl Saam, facility supervisor for the Ann Arbor canoe liveries.

Several comments during the Q & A session centered on the issue of housing density within the city. Eunice Burns, a long-time local activist and former Ann Arbor city councilmember, advocated for more flexibility in accessory apartments.

Doug Kelbaugh, a UM professor of architecture and urban planning, supported her view and wondered whether the city put too high a priority on parks, when what Ann Arbor really needs is more people living downtown. He said a previous attempt to revise zoning and allow for more flexibility in accessory units was shot down by a “relatively small, relatively wealthy, relatively politically-connected group. I don’t think it was a fair measure of community sentiment.”

Also during the Q & A period, Pete Wangwongwiroj – a board member of UM’s student sustainability initiative – advocated for the concept of gross national happiness to be a main consideration in public policy decisions.

The April forum was videotaped by AADL staff and will be posted on the library’s website – videos of the three previous sessions are already posted: on resource management (Jan. 12); land use and access (Feb. 9); and climate and energy (March 8). Additional background on the Ann Arbor sustainability initiative is on the city’s website. See also Chronicle coverage: “Building a Sustainable Ann Arbor,” “Sustaining Ann Arbor’s Environmental Quality” and “Land Use, Transit Factor Into Sustainability.“

Update on Sustainability Goals

The overall sustainability initiative started informally two years ago, with a joint meeting of the city’s planning, environmental and energy commissions. The idea is to help shape decisions by looking at a triple bottom line: environmental quality, economic vitality, and social equity.

In early 2011, the city received a $95,000 grant from the Home Depot Foundation to fund a formal sustainability project. The project set out to review the city’s existing plans and organize them into a framework of goals, objectives and indicators that can guide future planning and policy. The overall project also aimed to improve access to the city’s plans and to the sustainability components of each plan, and to incorporate the concept of sustainability into city planning and future city plans.

The Home Depot grant funded the job of a sustainability associate. The position is held by Jamie Kidwell, who’s been the point person for this effort. In addition to city staff, this work was initially guided by volunteers who serve on four city advisory commissions: park, planning, energy and environmental. Members from those groups met at a joint working session in late September of 2011. Since then, the city’s housing commission and housing and human services commission have been added to the conversation.

Over the past year, city staff and a committee made of up members from several city advisory commissions have evaluated the city’s 27 existing planning documents and pulled out 226 goals from those plans that relate to sustainability. From there, they prioritized the goals and developed a small subset to present for discussion.

Fifteen goals have been organized into four main categories: climate and energy; community; land use and access; and resource management. The draft goals are:

Climate & Energy

- Sustainable Energy: Improve access to and increase use of renewable energy by all members of our community.

- Energy Conservation: Reduce energy consumption and eliminate net greenhouse gas emissions in our community.

- High Performance Buildings: Increase efficiency in new and existing buildings within our community.

Community

- Engaged Community: Ensure our community is strongly connected through outreach, opportunities for engagement, and stewardship of community resources.

- Diverse Housing: Provide high quality, safe, efficient, and affordable housing choices to meet the current and future needs of our community, particularly for homeless and low-income households.

- Safe Community: Minimize risk to public health and property from manmade and natural hazards.

- Active Living: Improve quality of life by providing diverse cultural, recreational, and educational opportunities for all members of our community.

- Economic Vitality: Develop a prosperous, resilient local economy that provides opportunity by creating jobs, retaining and attracting talent, supporting a diversity of businesses across all sectors, and rewarding investment in our community.

Land Use & Access

- Transportation Options: Establish a physical and cultural environment that supports and encourages safe, comfortable and efficient ways for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users to travel throughout the city and region.

- Sustainable Systems: Plan for and manage constructed and natural infrastructure systems to meet the current and future needs of our community.

- Efficient Land Use: Encourage a compact pattern of diverse development that maintains our sense of place, preserves our natural systems, and strengthens our neighborhoods, corridors, and downtown.

Resource Management

- Clean Air and Water: Eliminate pollutants in our air and water systems.

- Healthy Ecosystems: Conserve, protect, enhance, and restore our aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

- Responsible Resource Use: Produce zero waste and optimize the use and reuse of resources in our community.

- Local Food: Conserve, protect, enhance, and restore our local agriculture and aquaculture resource.

A public meeting on March 29 to get input on these draft goals drew only a handful of people, but feedback can also be sent to the city via email at sustainability@a2gov.org.

Framing the Discussion: What Is Community?

As he did at the first sustainability forum in January, Dick Norton – chair of the University of Michigan urban and regional planning program – began the April 12 event by giving an overview to frame the subsequent discussion. He started by defining three terms: community, development and sustainability.

What is community? It’s not “I am an island unto myself,” he said, nor is it anarchy, nor dystopia, nor even utopia. Rather, community brings to mind images of the common, the social aspects of our nature, the notions of inclusiveness, identity and belonging. But it’s likely that most people in the room didn’t give much thought to what community means, he said.

The concept of development connotes improvement over time in the things we value, Norton said. It’s a sense of improving the human condition, in a qualitative way. Sustainability is harder to define, he noted. If we sustain our society, we keep it going and stable. But we want a just community, too – we want governments and those with power to treat the rest of us fairly. We also want happiness, Norton said, so we want to develop communities that we love, that are desirable places to live, work and play.

The trick is to do all these things simultaneously, he observed. So what institutions can help us get there? Government certainly plays a role, as do markets, to some extent. But nonprofits and religious institutions also play an important role. All of these entities interact, Norton said, adding complexity.

Norton also talked about the wide range of components that are necessary to build community. Citizen participation is key – residents need to be engaged. Fair and affordable housing, jobs, public safety, landscape and environment, services and amenities, historic preservation – all of these are important.

Norton also raised the issue of connectivity – how accessible are things? [This was a topic addressed at length by his UM colleague Joe Grengs at the Feb. 9 forum on land use and access.] Redevelopment is another component of community, but that’s set against concerns of gentrification. There are also issues of race, class and inclusiveness, Norton said. Who are we talking about when we talk about community?

Norton then laid out challenges faced in promoting community development. First, people are individuals, yet they’re also social creatures – we live in that tension, he said. Added to that, we’re a community of individuals with a variety of abilities, ambitions and circumstances. That causes us to behave differently, yet we still need to make communities work, given that variation.

Another challenge is the huge plurality of viewpoints and values that we hold about what’s important and valuable. We tend to want people to see things the way we see them, Norton said. But there are different preferences for whether things should be planned or evolve organically, for example, and those preferences influence how much government we want.

Norton also pointed to the challenge of randomness and uncertainty. That makes planning difficult, because you don’t know how things will play out. Measurement is also a challenge, he said. How do you measure whether you’re achieving your community development goals?

Community is vital, Norton concluded. The American ethos tends to be a cowboy mentality, the idea of individuals bootstrapping themselves and making it on their own. “That is just so untrue,” he said. People depend on communities to help them thrive.

Quality of Life: Community Foundation

Cheryl Elliott, president of the Ann Arbor Area Community Foundation, described the work of her organization. It was founded nearly 50 years ago, and its overall mission is to improve the community’s quality of life. AAACF manages more than 425 funds with over $60 million in assets, and administers scholarships, grants and other community support.

Elliott focused her comments on the quality-of-life issues of community, and said some of her remarks were informed by the recent book “The Economics of Place,” a publication of the Ann Arbor-based Michigan Municipal League. Quality of life plays a vitally important role in the community’s economic future, she said. When Elliott came to Ann Arbor as a University of Michigan freshman in 1969, “you could have shot a cannon down Main Street,” she said, and not hit anyone. It took a lot of collaboration to achieve the city’s vibrancy that you see today.

A wonderful community is crucial to attract and retain workers in a knowledge-based economy, Elliott said. An AAACF board member [Kevin Thompson] works for IBM and could live anywhere, she reported, but he chose to live in Ann Arbor. Quality of life and place wasn’t something that was previously considered as a factor in economic development. But today, a functioning, safe community isn’t enough, she said. It needs to be a place that inspires people, and that encourages creativity and innovation.

Elliott ticked through eight dimensions that affect quality of place: physical design and walkability, green initiatives, a culture of economic development, entrepreneurship, multiculturalism, messaging and technology, transit, and education. We need to think more regionally to achieve goals in these areas, she said.

Turning her comments to the role of culture in economic development, Elliott highlighted the importance of a healthy creative sector. Before Pfizer pulled out of Ann Arbor, its leadership talked about the city’s diverse cultural environment as an important factor in their desire to be located here, she said. Communities with healthy cultural sectors help create jobs, build a stronger tax base, and bring in more tourism.

Ann Arbor ends up on a lot of national Top 10 lists, Elliott noted, in large part because of the city’s quality of place, and a lot of that has to do with arts and culture – everything from the Ann Arbor Summer Festival and art fairs, to the University Musical Society and events like FestiFools. But “it doesn’t just happen,” she added. These things require partnerships and a lot of collaboration.

Elliott wrapped up her remarks by saying that the area has a creative, entrepreneurial nonprofit sector. She cited the example of a coordinated funding approach being taken to fund human services – a joint effort of the city of Ann Arbor, Washtenaw County, Washtenaw Urban County, AAACF and Washtenaw United Way, administered by the city/county office of community and economic development. No other community in the country is doing that, she said.

Public Safety

John Seto, Ann Arbor’s interim chief of police, told the audience that when he first was asked to speak at the forum, he wasn’t sure how public safety fit into the notion of sustainability. But after giving it some thought, he realized that most of what the police force does helps create a sustainable community, and it would be difficult to condense it into the limited time he had for his presentation.

So what does sustainability look like for public safety? he asked. It entails a vibrant downtown, safe neighborhoods, disaster preparedness, and a partnership with the community. Seto outlined a variety of ways that Ann Arbor police work toward these goals:

- Neighborhood crime watch: There are over 300 neighborhood crime watch captains in the city, working with a police coordinator who disseminates information throughout the city.

- Crime Stoppers: The coordinator for this Washtenaw County program works out of an office at the Ann Arbor police department. The anonymous tip line is 1-800-SPEAK UP.

- Justice Center e-kiosk: Located in the lobby of the new Justice Center at the corner of Fifth and Huron, an electronic kiosk allows users to make a police report, get traffic crash reports, pay a parking ticket, obtain a Freedom of Information Act request form and more.

- Online police reports: Several types of reports can now be made on the police department’s website, Seto said. They are typically crimes with no suspects, or reports that are needed for insurance purposes. The reports that can be filed if there are no known suspects include harassing phone calls; theft (but not of a home or business that’s been entered illegally); and vandalism. Reports of private property traffic crashes – if your vehicle was parked and struck by an unknown vehicle, for example – can also be made online, as can reports for lost or damaged property.

- CrimeMapping.com: Ann Arbor is now participating in this online mapping of crime data, which indicates the location and type of crimes. It allows users to search by date, crime type or address.

- Disaster preparedness: The city’s office of emergency management coordinates the Community Emergency Response Team (CERT), a countywide effort with more than two dozen members.

- CodeRED notification: Residents can sign up to be notified of crime alerts and other warnings – such as missing persons – through an automated phone notification system. It can handle 1,500 calls per minute, Seto said.

- Regional collaboration: Sustainability means collaborating to make the most out of your resources, Seto said. For policing, the city is collaborating both in everyday operations – like a joint dispatch unit with Washtenaw County, or mutual aid agreements with surrounding communities – and in special units like the SWAT and crisis negotiations teams.

Seto concluded by asking the audience how they would like to see the police department partner with the community. He said he hoped to hear some questions and comments about that later in the evening.

Affordable Housing

Jennifer L. Hall gave a shorter version of a presentation she made at the Ann Arbor Housing Commission’s December 2011 board meeting, which was her first meeting as executive director of the AAHC. Previously, Hall served as housing manager for the Washtenaw County/city of Ann Arbor office of community development.

She began by describing affordable housing. It’s defined relative to income levels – what is affordable to a higher income family is not necessarily affordable for a lower income family. For federal funding purposes, affordable housing means that a household is paying 30% or less of its gross income for housing, including utilities, taxes and insurance. Several programs of the U.S. Dept. of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) provide affordable housing assistance for low-income families – AAHC is one of the local entities that receives funding from these HUD programs.

Hall described a continuum of affordable housing throughout Washtenaw County. On one end are shelters for people who are homeless, including the Delonis Center, SafeHouse Center (for victims of domestic violence), Interfaith Hospitality Network’s Alpha House (for families), and SOS Community Services, which runs a housing access hotline. At the opposite end is market rate housing that is affordable. Within those extremes, Hall outlined a range of other housing assistance and types:

- Transitional housing (Dawn Farm, Michigan Ability Partners, Home of New Vision)

- Group homes (Synod House, Washtenaw Community Health Organization)

- Senior assisted-living (Area Agency on Aging 1-B, private sector)

- Nonprofit supporting housing (Avalon Housing, Michigan Ability Partners, Community Housing Alternatives)

- Senior housing (Lurie Terrace, Cranbrook)

- Public housing (Ann Arbor Housing Commission, Ypsilanti Housing Commission)

- Tenant vouchers (Ann Arbor Housing Commission, Ypsilanti Housing Commission, Michigan State Housing Development Authority)

- Private developments (Windsong)

- Cooperatives (Arrowwood, Pine Lake, Forest Hills, University Townhomes)

- Houses for homeownership (Habitat for Humanity and other nonprofits)

- Units within private developments (First & Washington, Stone School)

Ann Arbor’s owner-occupied housing market is getting more expensive compared to other areas nationally. According to data from the National Housing Conference, in 2011 metro Ann Arbor (Washtenaw County) ranked as the 87th most expensive housing market among the nation’s 209 metro areas, Hall reported. The median home price for the Ann Arbor metro area was $162,000. Just two years earlier, the median home price was $136,000, and metro Ann Arbor ranked 132 among the 209 metro areas, she said.

For the rental market, metro Ann Arbor also ranked 87th among the 209 markets in 2011, with an average monthly rent of $882 for a two-bedroom apartment. But that is a drop in the rankings from 2009, when the area ranked 51st with an average monthly rent of $940.

Hall noted that in an ideal world, every household would live in a unit it could afford – there would be units available for all income levels. But unfortunately, that’s not the case, she said. There’s a mismatch of availability and income, with some families paying more than 30% of their income for rent, and others paying far less than 30%.

There’s a growing need for more affordable housing in this community, Hall said. A study conducted by the Washtenaw Housing Alliance showed that in 2004, 2,756 people in Washtenaw County reported that they had experienced homelessness. In 2010, that number had grown to 4,738.

AAHC manages two main programs: (1) the Section 8 voucher program for Washtenaw, Monroe, and western Wayne counties; and (2) public housing units in Ann Arbor. Hall noted that the majority of people on wait lists for these programs fall into the category of extremely low-income families, with income at 30% or less of the Ann Arbor area’s median income. For a family of four, Ann Arbor’s median income is $86,300 – 30% of that would be an annual income of $25,900.

Hall then turned to the issue of fair and equitable housing. She showed the audience a map that indicated levels of poverty throughout the county, and pointed out that the map showed concentrations of poverty in downtown Ann Arbor, in the student neighborhoods around the University of Michigan. The city has benefited from its student population, in terms of federal funding, because students typically report poverty-level incomes, she noted. And because federal funding to communities from HUD is based on formulas that are tied to poverty levels, Ann Arbor receives more funding than it otherwise would, Hall explained. HUD is looking to change that formula, she added, but the formula hasn’t been changed yet.

In fact, this measure of poverty doesn’t reflect where most true low-income households are located, she said. For example, you’d see very different areas of poverty – primarily clustered in Ypsilanti and Ypsilanti Township – if measured by the number of people on public assistance.

Hall also observed that as people search for affordable housing and move further away from where they’d prefer to live, they often increase the amount they pay for transportation to get to work or to necessary services, like grocery stores. That increased cost often isn’t factored in to their housing decisions, she noted, and the more distant location can end up being more expensive overall.

Hall wrapped up by noting that federal funding for low-income housing is decreasing. In 1976, HUD’s budget was $86.8 billion. By 2010, its budget had dropped to $43.58 billion.

Parks & Recreation

Giving the presentation on Ann Arbor’s parks and recreation were Julie Grand, chair of the city’s park advisory commission, and Cheryl Saam, facility supervisor for the Ann Arbor canoe liveries.

The city has 157 parks and recreational facilities, 52 miles of pathways, and 2,008 acres of land – 72% of that land in open space. How the city cares for these resources makes an impact on the quality of life for residents here, Saam said.

Grand noted that one of the city’s draft sustainability goals is to have an engaged community. The goal states: “Ensure our community is strongly connected through outreach, opportunities for engagement, and stewardship of community resources.” One way to do that is through neighborhood parks, Grand said – this is a community that’s very engaged with its parks, and many neighborhoods are defined based on their relationships to nearby parks.

The city also engages residents through its senior center and other community centers, as well as through volunteer programs like the Give 365 program, Adopt-a-Park, or natural area preservation program. The thousands of volunteer hours benefit the parks system, Grand said, but also provide a way for people to feel connected to the community and give back in a meaningful way.

The parks system also supports the community goal of diverse housing, Grand said, through partnerships with the office of community and economic development. Parks land acquisition funds paid for property to expand the Bryant Community Center, for example. The city’s goal is to have a park within a quarter-mile of every residence, she said, and to make sure that low-income areas are well-served.

Grand said that having a safe and healthy community is also important to the parks system. Using best practices in stormwater management, protecting the Huron River ecosystem, and building non-motorized pathways are all examples of that. Parks and recreation also contribute to the city’s economic vitality, with facilities that draw people in, she said – the farmers market, golf courses, and other venues. “People want to live in communities with a vibrant parks system.” Parks also improve safety and add value to neighborhoods, she said.

Saam addressed the goal of providing an active living and learning community. The parks system provides both structured and unstructured active recreation, where people can get measurable health benefits and social interaction – summer camps, classes, or places just to relax and take a walk. A scholarship program offered by the parks system makes the venues and class offerings accessible to lower-income families.

The mission of the parks system is to provide open space and recreation that’s accessible, Saam said, and they strive for a broad range of services and facilities for people with disabilities. Recent examples include adding steps in Buhr pool, and plans to renovate the Gallup canoe livery, adding ADA-compliant pathways.

Saam also highlighted recent renovations in West Park and the new Argo Cascades, a bypass by the Argo Dam that’s just now being completed. And Grand pointed to land acquisition – both through the city’s greenbelt program, and for parkland within the city – as other examples of the parks system enriching the community.

Turning to the future, Grand said the parks system hopes to increase volunteer opportunities, expand non-motorized pathways and connections between the Huron River and the city’s urban core, continue paying attention to best practices in stormwater management, and emphasize making improvements to existing facilities – it’s important to improve what the city has before building something new, she said.

Grand also reminded the audience that the parks maintenance and capital improvements millage would be up for renewal in November. She encouraged people to get more information online or to attend an upcoming public forum on the topic. [Also see Chronicle coverage: "Park Commission Briefed on Millage Renewal."]

Questions & Comments

During the last portion of the forum, panelists fielded questions and commentary from the audience. This report summarizes the questions and presents them thematically.

Questions & Comments: Accessory Dwellings, Density

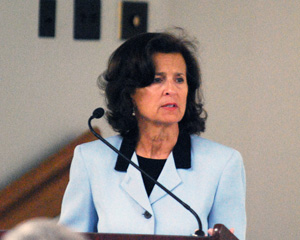

Several questions and comments centered on the issue of housing density within the city. Eunice Burns, a long-time local activist and former Ann Arbor city councilmember, described how she’d sold her house to her daughter and son-in-law, and now lives in the home’s garage that was renovated into an apartment for her. But because of existing zoning constraints, only a family member can live in an accessory dwelling, she noted – no one will be able to use the apartment when she’s gone. The city’s ordinances need to be revised to allow for more types of dwellings like this for a wider range of people, Burns said.

Eunice Burns advocated for zoning changes to allow for more accessory dwellings in Ann Arbor. Her record of public service includes the Ann Arbor city council, the board of the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority and the local officers compensation commission.

Ann Arbor faces a growing senior population, and many of them can’t afford senior housing like Glacier Hills, Burns noted. She recalled that when the city tried to change zoning for accessory dwelling units in the past, it had met with resistance. ”I’d like to see us work on this again and see if we can get it through this time,” she said.

(Burns concluded her remarks by putting in a plug for Huron River Day on July 15.)

The derailed effort that Burns mentioned would have changed the city’s zoning to make it possible for non-family members to live in accessory apartments. Wendy Rampson, the city’s planning manager, told the audience that the concern had primarily been about neighborhoods close to campus becoming too densely populated.

Conditions have changed since then, however. Rampson noted that according to the most recent census, Ann Arbor’s population has stabilized while the size of households has decreased. With fewer people living in individual homes, density isn’t as great as it was a few decades ago.

Dick Norton responded to Burns’ comments by taking a broader view. Like sustainability, the concept of community is difficult to define – it means different things to different people. Residents of a gated community might have a different definition than people who live outside of it. Norton pointed to sociologist Max Weber’s description of the Protestant work ethic in America – the idea of individuals making their way in society through hard work, and succeeding on their own merits. That concept influenced how people viewed the world, and complicated efforts to help people who are less well off, Norton said – people think that if someone is poor and homeless, it’s because they lack the ambition to work.

There are some deeply embedded ideological perspectives that need to be addressed, Norton said. Americans need to figure out how to ensure that people who are in less fortunate circumstances are at least doing okay and have opportunities to do better, he said. It requires people to open their minds a little bit. People tend to fear change and feel threatened if they’re asked to do something where there are no easy answers. Norton concluded by saying he knew he was preaching to the choir – the people who show up to the sustainability forums are already engaged in these issues, he said.

Doug Kelbaugh, a University of Michigan professor of architecture and urban planning, also commented on the topic of density. The carbon footprint of those living in the suburbs is dramatically higher than for urban residents, he noted. Increasing urban density would have the single greatest impact on reducing that carbon footprint – saving energy, the amount of land that’s used for development, the amount time people spend commuting, and more.

Kelbaugh said he loves the city’s parkland, but he sometimes thinks there’s too much of it – what the city really needs is more people living downtown. Perhaps parkland is being over-prioritized.

Regarding sustainability and affordable housing, Kelbaugh said the lowest-hanging fruit to address that issue is accessory dwellings. The previous attempt to revise zoning and allow for more flexibility in accessory units was shot down by a “relatively small, relatively wealthy, relatively politically-connected group,” he said. “I don’t think it was a fair measure of community sentiment.”

There cannot be too many people living downtown, Kelbaugh concluded – the more, the better – and Ann Arbor is far from hitting the upper level of the population it can sustain.

Julie Grand, chair of the city’s park advisory commission, said she’d argue that the city needs greenspace to allow people room to breathe. There also needs to be recreational opportunities for residents, she said.

Questions & Comments: Being Proactive

Ann Larimore, a UM professor emeritus of geography and women’s studies, followed up on the issue of density by saying that it doesn’t help to use the word in a general way. There are different kinds of density – of families with children, of low-income people, of students living in high-rise apartment buildings, of people who only use their Ann Arbor homes on football weekends and otherwise those homes sit empty.

But Larimore said her question related to creating a community that’s proactive. An increase in private high-rise apartments aimed at students has been a national trend that’s also seen in Ann Arbor, she said, often fueled by out-of-town development money. Pfizer pulled out of Ann Arbor several years ago and UM bought its large research campus, thus taking that property off of the local tax rolls and creating an employment crisis. There’s also been more severe weather because of global warming, she said. What can the community do to be more proactive to these kinds of outside events?

Dick Norton noted that by the very nature of these events, it’s difficult to be proactive. But it’s possible to build a community that’s adaptable and resilient, he said. Creating a diverse economic base is also important, so that the community is not dependent on any one entity like Pfizer or UM.

Norton said he teaches planning, which includes taking stock of how things currently stand and reflects on where you’d like to go. But a plan is never a fixed thing, he added. You need to build in a resiliency and a capacity to respond as conditions change. That’s an unsatisfying answer, he acknowledged, but it’s a complicated world.

Jennifer Hall of the Ann Arbor Housing Commission responded by saying that you can’t discriminate against the type of people who might move into a building. You can plan for the type of building, but not the type of people who ultimately live there, whether they be students or the elderly. It’s a fair housing issue, she said.

Questions & Comments: Gross National Happiness

Pete Wangwongwiroj introduced himself as a University of Michigan student who’s active in the campus sustainability movement – he’s a board member of the student sustainability initiative. He said he’s shifted the focus of his studies from environmental issues to happiness. Happiness is an issue that’s bipartisan and that can unite people, he said. The country focuses its attention on the gross domestic product as an economic indicator, he noted. But there’s a new concept that deserves consideration: gross national happiness. Wangwongwiroj advocated that this concept should be the main consideration of public policy decisions. He asked the panel what has been done in Ann Arbor regarding the well-being and quality of life for residents, and what more can be done?

Jennifer Hall observed that there are some interesting new studies related to that topic and public health, looking at how your environment can make you happy or depressed. People are more depressed who live in neighborhoods with buildings that have boarded up windows and are in disrepair, with uncollected garbage and broken streetlights. She related an anecdote about developers who came to Ann Arbor and were interested in building affordable housing. Hall took them on a tour of one of the city’s low-income neighborhoods – the Bryant area, on the southeast side of Ann Arbor – and reported that the developers were shocked that it was considered low-income, because it was so much nicer than the low-income areas they were used to seeing elsewhere. So Ann Arbor is doing relatively well, she said.

Cheryl Elliott pointed to the involvement of youth as a community resource, through volunteering in different organizations – in youth advisory councils, for example. The community can leverage that enthusiasm and creativity, she said: “They aren’t jaded yet.” In general, a more engaged community does bring more happiness to residents, she said. Elliott also pointed to public events like the recent FestiFools parade as another way that Ann Arbor brings happiness to residents.

John Seto of the Ann Arbor police said that many times, it’s the smaller things that affect quality of life. Many complaints that the police receive have to do with quality-of-life issues – a neighbor’s barking dog, or uncut grass. It’s important not to lose sight of those smaller issues, he said, adding that Ann Arbor does a good job of that. Any complaint is important, he said.

Wendy Rampson noted that as the sustainability project moves ahead, the next step – after a consensus is reached on goals – will be to develop objectives and metrics to measure progress. She asked Wangwongwiroj to fill out a comment card, and said the group that’s working on these sustainability goals would be happy to consider adding happiness as a factor.

Dick Norton noted that happiness is based on a sense of safety and stability, but also on the relationships you build. The problem is that there’s too much focus on GDP, especially at the national level. The government needs to rethink that approach, and people need to resist the constant bombardment of advertising to buy more stuff. Norton also recommended getting backyard chickens to increase happiness – chickens are very calming and fun to watch, he said.

After the panelists finished weighing in, Doug Kelbaugh, a UM professor of architecture and urban planning, stepped to the microphone to make a comment related to accessory dwellings and density (see above). But he prefaced his remarks by saying that although a happiness index might sound frivolous, in fact it’s getting a lot of serious professional and academic respect.

Questions & Comments: Spending Priorities

Thomas Partridge said he wanted to know how the community could prioritize, when there was no sustainable, progressive tax base. He said he’s called on the Ann Arbor city council and Washtenaw County board of commissioners to place a Headlee override on the ballot. He also wondered why there is a dedicated millage for open space and parkland, while at the same time there are homeless people living in parks and under freeway overpasses. The city isn’t giving priority to human values like affordable housing, health care, transportation, education, human rights, and adequate fire and police protection.

Panelists responded primarily by pointing to examples of collaboration. Cheryl Elliott talked about the collaborative funding approach used to support local human service organizations – a joint effort with the city of Ann Arbor, Washtenaw County, the Urban County, Washtenaw United Way, and the Ann Arbor Area Community Foundation. They aren’t working in silos, she said. They’re communicating and working more effectively with the resources they have.

Julie Grand noted that the city parks collaborates with the county – the proposed Ann Arbor skatepark project is an example of that, she said, and also involves the Ann Arbor Area Community Foundation. The county’s parks and recreation commission has committed $400,000 to that project.

Grand also reported that when the city park commissioners discuss land acquisition, the first question they consider is how much it would take away from the city’s tax base. She said they’ve determined that the Headlee rollback isn’t significant enough to be a real concern.

Jennifer Hall thanked Partridge, saying that she appreciated his advocacy for the same people that she was trying to support. She raised the issue of Michigan being a “home rule” state, making it difficult to overcome the jurisdictional boundaries of townships, cities and villages. The city of Ann Arbor’s tax rate is much higher than the townships, she noted, so many people want to live in the townships and pay lower taxes, yet they use the amenities of the city. It results in some “weird dynamics,” she said. Hall also noted that Ann Arbor is very generous in its funding of housing and human services for low-income residents.

The Chronicle could not sustain itself without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of local government and civic affairs. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

This is what makes towns like Ann Arbor different. Presuming there is some follow-through and significant action, this is what will help towns survive and prosper in the future.

The topic made me think of a book recommendation: Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010, by Charles Murray.

I wouldn’t count on any significant action, Tim. This is just one in a long line of “feel good” planning studies that take up a lot of staff time and citizen effort only to be stuffed into a drawer and forgotten.

There will likely be a final report that is lauded by the planning commission and praised by council members seeking re-election, just before they take a symbolic vote on accepting it. But instead of incorporating it into the master plan or more importantly, the zoning ordinance, it will quickly be forgotten as the next “study du jour” is requested by Council. Only when some future controversial issue comes along will people ask, “Hey, I thought we fixed that back in 2012 with that what-cha-ma-call-it study?” They will then be told no, that in fact it did not get formally addressed, and its presence in a study report carries no legal weight or even any political weight, if it goes against the current council group-think.

Meanwhile, our zoning ordinance remains a sloppy mish-mash that is not in compliance with the 2006 Zoning Enabling Act, and our master plans are overdue for updating, with many popular provisions having never been incorporated into the zoning, some 20 years after the fact.

Sorry. Does that sound a little cynical?

Tom,

Were I not an A2 expat who lived there for 30 years, I’d say it sounds cynical. But it doesn’t. My own opinion is that council suffers from ADHD and a lack of passion or commitment. Nothing would turn opinions faster than council and the city admin actually DOING something great, and not just talking about it ad infinitum.

A2 is a very good town. But it still hasn’t learned how to be great.

I’m kind of worried about follow through, too. There some bitchin’ (yeah I said it) ideas in that article but a) what are the plans for follow through, b) how can community members help? and c) when we will check up on these ideas to see which ones have happened or are being worked on?

If Professor Kelbaugh wants more density downtown, how about some plans to provide sufficient grocery shopping nearby to accommodate more residents. As it is, most urban dwellers have to drive several miles to reach a supermarket, which negatively adds to the carbon footprint. As for parkland as a priority, it’s one of the things that keeps Ann Arbor a decent place to live in comparison to communities such as West Bloomfield and Farmington Hills. I’ve been an Ann Arborite since I first came to this country in 1954 and it’s certainly one of the main attractions of the city as far as I’m concerned.