In the Archives: Poison Pages

A second-floor shelf of University of Michigan’s Buhr book storage facility contains Michigan’s single most dangerous book.

It is one of only two known copies to exist in the state. If not for its historical importance, even the most fervent bibliophile might agree: the fewer copies in the world the better.

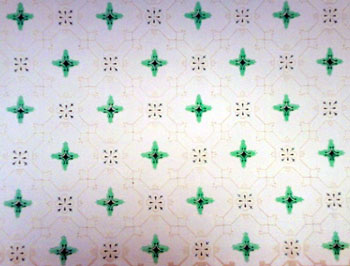

“Shadows from the Walls of Death” is dangerous not in the sense of a book containing radical ideas. Nor is it dangerous in the way a bomb-building manual might be. In fact, after the title page and preface, the following 86 pages, each one measuring about 22 by 30 inches, contain no printed words at all.

Michigan State University holds the other copy of “Shadows” in its Special Collections library division. The volume is sealed in a protective container, and each page is individually encapsulated.

Prospective “readers” of “Shadows” at the Buhr building must wear blue plastic protective gloves. During a visit to the Buhr some days ago, the book was wheeled out slowly on its individual cart. The marbled pattern on the cover showed through a protective thick-gauge plastic bag.

I held my breath as I gingerly eased open the cover, and while “reading” the pages I was careful to avoid any skin contact. “Shadows” is saturated with a deadly amount of arsenic.

UM alum Robert Kedzie created “Shadows from the Walls of Death.” After receiving his degree with the medical school’s first graduating class, in 1851, Kedzie established a medical practice in Kalamazoo and later Eaton County’s Vermontville. He left his practice, along with his wife and three sons, to serve as a Civil War surgeon with Michigan’s 12th Regiment. Kedzie was captured and imprisoned at Shiloh, but paroled.

In 1863 he returned to Michigan to chair Michigan Agricultural College’s (MSU’s) chemistry department. Some three decades later, Kedzie imported 1,700 pounds of beet seeds from Europe in a campaign to assess the suitability of Michigan soil for sugar beet production. The seed was sent to 400 Lower Peninsula farmers. Of those, 228 responded and mailed beets back to Lansing for analysis. They were found to contain 14% sugar. Michigan’s beet sugar industry was born.

Before donning the mantle of “Father of the Michigan Beet Sugar Industry,” Kedzie was elected to serve with the state’s board of health when it formed in 1873. He chaired the committee on “Poisons, Special Sources of Danger to Life and Health, &c.” Kedzie wasted no time in reporting his chief concern in an essay, “Poisonous Papers,” included in the Board of Health’s inaugural 1874 report.

He called attention to a problem raised by Massachusetts’ board of health in 1872 – the widespread use of wallpaper colored with arsenical pigment.

The story of Napoleon poisoned by arsenical wallpaper while imprisoned on the island of St. Helena in 1815 is a familiar rumor. Largely forgotten, however, is that arsenical wallpaper was common and widely used in Michigan, Massachusetts, and elsewhere in the 19th-century United States. In 1887, the American Medical Association estimated that between 1879 and 1883, 54–65% of all wallpaper sold in the United States contained arsenic, a third of which at dangerous levels. Over time, the poisonous pigment could flake or be brushed off the wallpaper and float in the air as inhalable dust or settle on furniture in the home.

Kedzie cited several cases of wallpaper poisoning in his essay, including one from a family in Manchester in Washtenaw County.

The walls of one bed-room were covered with a paper the ground work of which was stone color with bands of bright green ornamented with gilt. The daughter, Emma, aged 9, occupied this room for several months. Soon after occupying the room her health began to fail, and she exhibited the following symptoms: Lameness, resembling rheumatism, darting pains in various portions of the body; languor in the morning, feverishness, pains in the head and about the frontal sinuses, sores in various parts of the body, faint spells, turning white about the mouth, and great loss of flesh. The best medical advice that could be procured was obtained, but no essential improvement followed. Whenever she left home for a few weeks her health improved; but she relapsed into her former condition on returning home.

Kedzie tested the paper and found it contained a high level of arsenic. Emma was removed from the room and regained her health.

An Economical Dye

Originally a byproduct of the European mining industry, arsenic offered mining companies a means of profiting from a waste product, and offered manufacturers a means of obtaining a cheap dye. Thousands of tons were annually imported to the United States. The substance produced lovely hues ranging from deep emerald to pale sea-green. Arsenic could also be mixed into other colors, giving them a soft, appealing pastel appearance.

The first application of arsenic as a pigment was as a paint dye. The pale green shade caught on as a “refined” color. American manufacturers began using arsenic to color a range of consumer goods. Children’s toys were painted with arsenical paint. Arsenic-dyed paper was used in greeting cards, stationery, candy boxes, concert tickets, posters, food container labels, mailing labels, pamphlets, playing cards, book-bindings, and envelopes –envelopes the sender had to lick.

“A professor at the Agricultural College,” wrote Kedzie in “Poisonous Papers,” “brought home a package of lead pencils around which was a broad band of beautiful green paper. His little children, attracted by the beautiful color of this paper, wanted it to play with, but he handed it to me for analysis, and I found it contained enough arsenic to poison all of them.” Kedzie went on to cite cases involving a baby’s toy box decorated with green paper, a U.S. Express Co. package with a green mailing label, and green store price tags, all of which tested positive for arsenic.

Arsenic Elsewhere

In 19th-century Michigan, arsenic served as a home rat poison and insecticide – even childrens’ stuffed animals were dusted with it by manufacturers to prevent infestation. Arsenic appeared in green lampshades, cosmetics, and copper cookware. It was used to color candy and glaze fudge. Cheesemakers sometimes threw a pinch or two into the cheesemaking vat in the hope of killing ptomaine.

Ypsilanti druggist Frank Smith sold Paris Green and wallpapers that like as not were impregnated with arsenic, as seen in this 1878 ad.

Arsenic was an ingredient in many patent medicines. As late as 1921 the American Medical Association was still finding arsenic in patent medicines that included Blue Bell Kidney Tablets, Botanic Blood Balm, Wildroot Dandruff Remedy, Dander-Off, Dr. Miles’ Restorative Nervine, La Franco Vitalizer No. 200, and others. Arsenic was also used in mainstream medicine as a treatment for syphilis.

Arsenic was extensively used in 19th-century Michigan agriculture as the ubiquitous insecticide “Paris Green.” It was dusted on tomatoes, potato foliage, cabbage, cucumbers, grapes, melons, and sprayed on fruit trees.

Arsenic-dyed cloth led to an 1860s fad for emerald-green tarlatan-fabric ball gowns. Luckily the trend was short-lived. The 1884 annual report from Massachusetts’ State Board of Health, Lunacy, and Charity said, “Attention has very frequently been called to the presence of large amounts of arsenic in green tarlatan, which has given rise so many times to dangerous symptoms of poisoning when made into dresses and worn, so that it is very rare now to see a green tarlatan dress.” The report continued:

This fabric is still used, however, to a very dangerous extent, chiefly for the purposes of ornamentation, and may often be seen embellishing the walls and tables at church and society fairs, and in confectionery, toy and dry-goods stores. The writer has repeatedly seen this poisonous fabric used at church fairs and picnics as a covering for confectionery and food, to protect the latter from flies. As is well known, the arsenical pigment is so loosely applied to the cloth that a portion of it easily separates upon the slightest motion. Prof. Hoffmann after examining a large number of specimens estimated that twenty or thirty grains of the pigment would separate from a dress per hour, when worn in a ball-room.

Two to three grains (130-195 milligrams) could prove fatal if ingested.

Arsenic was also used to dye stockings, underwear, curtains, millinery decorations, artificial flowers, and cloth linings for bassinettes and cribs in a variety of colors. Green flannel boot linings impregnated with arsenic allegedly killed several California gravel miners in 1875. Arsenic poisoning is still a concern for modern-day reenactors who wish to wear authentic Victorian-era clothing.

Mysterious Poisonings

Skin ulcerations are one symptom of arsenic poisoning. Others include headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea, patches of skin discoloration, hair loss, coughing, convulsions, and neuropathy in the hands and feet.

In 19th-century Michigan, those symptoms pertained to a range of diseases. Arsenic poisoning was often diagnosed as conditions that included “general debility,” neuralgia, consumption (tuberculosis), cholera, rheumatism, gastritis, dysentery, or paralysis – all of which commonly appear as causes of death on old Michigan death certificates.

Sometimes the symptoms were not produced by a chronic condition caused by long-term exposure, but by acute conditions deliberately and maliciously created. Over the years, UM served as the state’s resource for toxicological examinations in arsenic poisoning cases.

In the summer of 1846, the Oakland Gazette reported suspicion surrounding the death of one Harriet Russell. Her remains were disinterred and her stomach and intestines sent to Ann Arbor for testing. Silas Douglas of the chemistry department tested the samples and found arsenic. Russell’s husband was taken into custody.

In the summer of 1861, the Grand Traverse Herald reported another suspicious death. Douglas analyzed the stomach contents of one Nicholas Frankinburger of Traverse City, finding a large quantity of arsenic. Douglas’ skills were employed again in 1865 in the notorious Battle Creek Haviland murder case in which Sarah Haviland was accused of poisoning three children. His findings led to her conviction.

In addition to Douglas, other UM toxicologists and pathologists served as analysts and expert witnesses in arsenic poisoning cases. As arsenic was a late 19th-century ingredient in embalming fluid, post-mortem embalming could hide ante-mortem poisoning attempts. In the spring of 1892 the wife of Matthew Millard, a leading businessman of Ionia County, took ill and died. Her husband, a onetime undertaker, embalmed her with injections of arsenic in her mouth and rectum and had her buried.

Due to suspicions of poisoning, Mrs. Millard was exhumed 105 days later and several tissue samples were analyzed. Mrs. Millard was re-buried, then re-exhumed again so that more samples could be taken. Arsenic was found in her internal organs.

The case went to court. The leading toxicological textbook of the day taught that arsenic could not spread to internal organs after death; therefore, said the prosecution, Mrs. Millard’s husband must have poisoned her. Robert Kedzie and UM toxicologist Victor Vaughn testified for the defense, saying that arsenic could indeed spread throughout the body after death; the presence of the poison in the internal organs did not necessarily indicate ante-mortem poisoning. To prove it, Vaughn duplicated the arsenic injection procedure on a corpse and buried it. When exhumed, it was found that the arsenic had spread to the internal organs. Millard was ultimately acquitted.

In the celebrated 1895 New York case of Mary Alice Fleming’s alleged matricide by clam chowder, Vaughn testified for the prosecution. “Dr. Vaughn is the discoverer of tyrotoxicon, the ptomaine poison found in stale milk, and enjoys a world-wide celebrity for original research in toxicology and physiological chemistry,” wrote the June 11, 1896 New York Times. The story went on to say that Vaughn testified about the types and classifications of poisons and described in detail the symptoms of arsenic poisoning. He agreed that it appeared that Mary Alice’s mother had apparently died of arsenic poisoning. Though the prosecution’s case was strong, popular sentiment of the time ran against the death penalty for a woman, and Mary Alice was acquitted.

Vaughn, along with UM pathologist Alfred Warthin also provided analyses in the 1909-1911 Sparling family poisonings in Ubly, near Bad Axe in Michigan’s Thumb area. The father, John Sparling and three of his four sons, Peter, Albert, and Scyrel, died from arsenic and strychnine poisoning in a case that involved alleged improprieties between the mother and a local doctor, Robert Macgregor. Macgregor encouraged her to take out life insurance policies on her family members. Vaughn and Warthin found evidence of arsenic poisoning, and Macgregor went to Jackson State Prison with a life sentence, though he was later pardoned by Governor Ferris.

Nearly four decades earlier, Robert Kedzie had delivered his own verdict: arsenical wallpapers must be eliminated from the state. In 1874 he collected numerous wallpaper samples from Detroit, Lansing, and Jackson stores, cut them into pages, and had them bound into 100 books which he distributed to libraries around Michigan.

The dainty and artistic wallpaper samples stand in contrast to a dire Biblical quotation on the title page of “Shadows of the Walls of Death”:

And behold, if the plague be in the walls of the house, with hollow strakes, greenish or reddish, … Then the priest shall go out of the house to the door of the house, and shut up the house seven days. … And he shall cause the house to be scraped within round about, and they shall pour out the dust that they scrape off without the city into an unclean place.

Kedzie’s public health campaign was reported to have poisoned one lady who examined the book, but it otherwise effectively publicized the dangers of living in a house papered in arsenic. Scraps of arsenical wallpaper may still be found here and there in historical homes, now merely an antique curiosity to be removed for safety’s sake. It is no longer a silent everyday threat disguised as beautiful patterns on the walls.

Mystery Artifact

Last month, Jim Rees and Poohbah correctly guessed that the object was a blowtorch (honorable mention goes to Irene Hieber for guessing that it was an acetylene torch – you were right about the torch part).

This artifact is a recent acquisition to the author’s collection (translation: scavenged from a curbside pile of junk while walking the dogs) and I can’t wait to try it out!

On second thought, I think I can wait.

This month’s Mystery Artifact dates from an era of more leisurely communication. This tiny cylinder had a specific function, but what was it?

Where in the house could you find it?

What did it do?

Take your best guess and good luck!

Laura Bien is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives” and “Hidden History of Ypsilanti.” Contact her at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our columnists like Laura Bien and other contributors. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle (arsenic free!), please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

Laura, do you know what process they used to test for arsenic? Just curious because now all the TV CSI-types throw a test-tube into a machine and . . . voila! I wonder how it used to be done.

The object looks like a postage stamp dispenser (for a roll of stamps).

Hi Joan; Kedzie gave instructions in the 1874 state Board of Health report on how to test wallpapers in stores for arsenic content.

“The green arsenical colors are readily soluble in ammonia water. If a little ammonia water poured on the paper discharges the green color, or produces «uch a change in the color as indicates the removal of green, the paper alionld be rejected, as it probably contains arsenic. To identify the presence of arsenic in any paper, wet the paper with ammonia water, pour off this water on a clean piece of glass and drop into this a crystal of nitrate of silver, or a small piece of lunar caustic. If a yellow precipitate forms around the •crystal it indicates the presence of arsenic.”

Presumably shoppers would have their crystal of nitrate of silver or their lunar caustic handy.

Lots of good arsenic information here: [link]

There is a dangerous amount of natural arsenic in Washtenaw County, if you drink well water, and don’t know of recent test results, get it tested. If your neighbor is okay, get it tested anyways, the results can be dramatically different depending on the depth of the well. Follow the links provided to find out how to get water testing kits, Radon too. Presumably municipal water is tested, but if you are in a small system with shared pumps in a development be wary.

No guess on the object, stamp dispenser sounds good to me. You can put a wet sponge in the bowl on top for licking stamps and envelopes too.

That is a great article, Laura! I read a (fiction) book once, set in the 1800s, about a man who died mysteriously. His wife had a habit of bringing him white powdered cakes every day and he took a bite of one, asked “How could you?” (or something like that) and then died. They tested the cake for arsenic but it was negative (also, the wife ate the same cake and didn’t die). Come to find out, he was an arsenic addict who ingested it, daily, on those cakes; the wife killed him by giving him a cake WITHOUT arsenic. I’m not sure if that is scientifically accurate or not, but it was pretty interesting :)

Laura, you have the rest of that newspaper available I presume. Does all this stuff in the ad about bears and turkeys have something to do with the Russo-Turkish War of that year? And if so, what does it have to do with the druggist, Mr. Smith; does it prevent importing his stocks somehow?

The mystery artifact is a stamp dispenser. It neatly holds a coil of 100 postage stamps. The outside end of the coil is fed through the slot, making it easy for the owner to tear off one stamp at a time, along the perforation. The device would be stored in the home office or wherever one addresses and stamps envelopes. I have a plastic version that I still use today.

Thank you for that link, Cosmonican! Arsenic from well water is the current leading cause of arsenic poisoning in the States; it is important, as you say, to have well water tested. Municipally-supplied water is tested before it reaches one’s home.

TeacherPatti: That book sounds interesting, do you recall the title? I haven’t come across any stories of physical addiction to arsenic; perhaps this was a psychological addiction.

Arsenic was a part of many patent and mainstream medicines in the 19th century; in the latter, it was there as a relic from the days of “heroic medicine” when it was thought that the power of a serious illness could best be fought with a powerful (sometimes fatal) treatment like mercury (calomel), bloodletting, violent vomiting caused by purgatives, or arsenic. Calomel was in use well into the 20th century; I’ve seen it come up as a medicine in a 1919 Ypsilanti diary to give one anecdotal example.

Colin: As it turns out this mystery artifact is from my own ramshackle collection of “junque,” and I use it all the time. It’s less than an inch from my keyboard at this very moment (hint). I can’t decide if it’s cool or kind of pathetic that I can pluck random old-fashioned often entirely useless (blowtorch from last column; no way am I firing that baby up) stuff from my own home. :)

To add one more comment for Teacher Patti: Some of the (many!) accidental historical arsenic-poisoning cases came about when someone thought that this odorless, flavorless white powder was a cooking ingredient (this is white arsenic, not arsenical Paris green, which is, uh, green). Read one story of a farmer who hid a tin of white arsenic, left-over rat poison, in a clock-body of all places in an attempt to keep it away from accidental ingestion. Years later a house-servant found it, thought it was (then-expensive) sugar, and mixed it into a cake with deadly results.

You’re not going to fire up the blowtorch? It’s kind of fun. You fill the pan with gasoline and light it, making a big smoky flame. This heats the generator up enough to vaporize the gas. Once it’s going, the generation is self-sustaining.

Best to do this outdoors. My grandfather was a big fan of gas appliances (his grandfather owned oil wells). He installed a gasoline stove in my grandmother’s kitchen in 1913. It blew up and nearly burned the house down. He also owned the first gas car in Luckey, Ohio, which luckily didn’t blow up. Coincidentally, my wife’s great-grandfather owned the first car in Port Huron.

Jim: That is interesting; gasoline stoves were a big cause of fires in 19th-century Ypsilanti homes. The gasoline reservoir was in a gravity-fed can kind of suspended via pipe above the stove itself. They were touted as a way to keep your kitchen cool in summer versus laboriously firing up a coal or wood stove. And indeed, the kitchen was a lot cooler when half of it was burned to the ground…

19th-century insurance policies used to base their rates on whether or not you had a gasoline stove, and how many per multi-family house…the stoves were known to be deadly.

Both my husband and I are what I guess you could call “pyros,” but firing up an ancient gasoline blowtorch of uncertain integrity, soldering, &c., is probably a bit more excitement than I’m looking for. Speaking as someone who looks at arsenic books for fun. :D

Thanks to Google, I found it: [link]

The story I talked about was actually the “back story”, told in flashbacks…I don’t even remember how the actual mystery was resolved :)

Thank you for the link, TeacherPatti!