Round 3 FY 2014: Housing Commission

After a Feb. 11, 2013 budget work session that included separate presentations on the city’s capital improvements plan (CIP) and the Ann Arbor Housing Commission (AAHC), both of these topics came up again briefly at the city council’s most recent regular meeting.

During communications time for the council’s meeting on Feb. 19, 2013, Stephen Kunselman (Ward 3) expressed his view that the CIP should start including the 360 units of public housing managed by the AAHC.

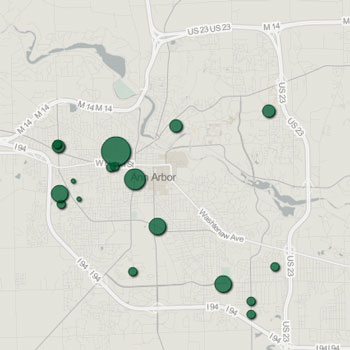

Ann Arbor Housing Commission properties. The size of the dot is proportional to the number of units in the location. (Map by The Chronicle. Image links to interactive map.)

Kunselman’s argument for future inclusion of AAHC properties in the city’s CIP is based in part on the fact that the city of Ann Arbor currently holds the deeds to those properties. But his broader point is that he’s opposed to the city relinquishing title to the properties – as part of a proposal made to the council by AAHC executive director Jennifer L. Hall. Hall has served in that capacity for about a year, and began her Feb. 11 presentation at the council work session with an overview of improvements that AAHC has achieved since she took the post.

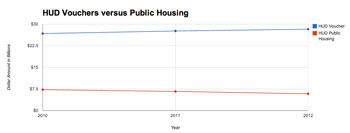

Hall’s proposal stems from a need to cover an estimated $500,000 per year funding gap for needed capital investments, coupled with a perceived shift in priorities by the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in its funding strategy. That shift is somewhat away from subsidized public housing, where rent is subsidized in units owned by a housing commission. [Ann Arbor's situation is apparently unique – because the city, not the AAHC, holds the deeds.] While HUD still allocates several billion dollars nationally for public housing, it subsidizes even more in programs that are based on vouchers. And based on the last three years, the trend is toward more funding on the federal level for vouchers than for public housing.

Some HUD vouchers are tied to a tenant – a person. A potential tenant can take that voucher to a private landlord – and it’s the tenant who receives the rent subsidy, wherever that tenant is able to rent a place to live. Other HUD vouchers are tied instead to privately-owned property, and whoever lives in that private project receives the rent subsidy.

The strategy that Hall will be asking the council to authorize is one that converts AAHC properties to part private ownership, in order to take advantage of project-based HUD vouchers. The private ownership of the AAHC properties will also allow the possible use of tax credit financing to pay for needed capital investments – roofs, boilers, plumbing and the like.

The conversion to project-based vouchers would take place under HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program. To set the stage for that, the board of the AAHC selected a co-developer at its Jan. 10, 2013 meeting: Norstar Development USA.

The council would need to take two specific steps in order to proceed with the RAD: (1) approve the contingent transfer of the city-owned AAHC properties to the AAHC; and (2) approve a payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) for the properties so that they’d owe just $1/unit in property tax per year. As city-owned properties, no property tax is currently owed. Without the PILOT provision, taxes would be owed. Requests to take those steps are expected to come to the council in March. March will also be a period during which public hearings will take place on this issue.

Although Kunselman expressed clear opposition to the idea of transferring the deeds, and Mike Anglin (Ward 5) joined him in expressing significant skepticism, other councilmembers were more positive. They still had several questions about the complexities and the risks associated with the RAD program. [For more background on the AAHC’s efforts to prepare for the RAD program, see Chronicle coverage: “Housing Commission Eyes Major Transition.”]

The Feb. 11 budget work session included the 15th District Court and the capital improvements plan (CIP). A session held on Feb. 25 covered the fund-by-fund budget picture for the next two years. Presentations on those topics are covered in separate Chronicle reports. The council’s discussion of its budget priorities – identified at a planning retreat late last year – is expected to begin at a March 11 work session.

Highlights of Hall’s Feb. 11 presentation to the council included accomplishments of the housing commission over the last year, as well as a description of the properties Hall considers to be in the best condition, contrasted with those in the worst condition. She then walked the council through the key elements of the RAD program. Councilmembers had a range of questions.

Housing Commission Accomplishments

Ann Arbor Housing Commission executive director Jennifer L. Hall has held that position for a bit over a year. The AAHC board made the decision to hire her at its Oct. 19, 2011 meeting. At her first meeting of the board, on Dec. 21, 2011, she sketched out a possible expansion scenario.

Jennifer L. Hall, executive director of the Ann Arbor Housing Commission, addressed the city council at its Feb. 11 work session.

But Hall’s presentation to the city council on Feb. 11, 2013 focused on a path to sustaining the existing units of housing administered by the AAHC. To be eligible for the RAD program, for example, AAHC public housing could not have a “troubled status” designation. Hall was able to report to the AAHC board last fall, at its Oct. 17, 2012 meeting, that AAHC’s public housing operations no longer had a “troubled status” designation from HUD.

The news about AAHC’s public housing program emerging from the “troubled status” designation to achieve “standard performer” status was accompanied by even better news for AAHC’s voucher program (Section 8). After previously having “troubled” status, the AAHC voucher program is now considered by HUD to be a “high performer.”

Some of the data underlying the better status includes the time it takes AAHC to make a public housing unit ready for the next tenant after one tenant moves out – the “unit turn” time. Three years ago, based on minutes from the Jan. 20, 2010 board meeting, one subset of the AAHC public housing units had turn times of as much as 270 days. But that’s improved to 21 days on average, with another 14 days to occupy a unit – for a total of 45 days on average to get a new tenant into a unit after the previous tenant moves out.

Because HUD gives AAHC a rent subsidy for a unit only if it’s occupied, an unoccupied unit translates to zero revenue for AAHC. The overall vacancy rate for AAHC public housing has improved from 95% (12-20 vacant units) to 99% (1-5 vacant units).

Toward the end of the council’s session on AAHC, Chuck Warpehoski (Ward 5) told Hall that he appreciated the leadership she’d shown during her short time as head of AAHC. That helped him have confidence in what she was proposing. And despite his opposition to the proposed conversion through the RAD program, during the “thank you mode” of the presentation, Kunselman added his thanks to Hall, saying that he was most impressed with the turnaround.

Housing Commission Properties

At the council’s Feb. 11 work session, AAHC executive director Jennifer L. Hall gave councilmembers an overview of some of the housing commission’s properties – from the best-maintained units to those with problems.

As an example of the commission’s best-maintained properties, Hall cited Baker Commons, a building with 64 one-bedroom apartments located in downtown Ann Arbor at the intersection of Packard and Main streets. Hall described Baker Commons, which was built in 1980, as the housing commission’s “best, most beautiful building.”

Baker Commons still requires maintenance, however. Last fall, on Oct. 3, 2012, the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority board allocated a $260,000 grant for the replacement of the roof on Baker Commons. The work was done in mid-November. Hall also showed the council before-and-after slides of the carpeting in a common area, replaced by marmoleum.

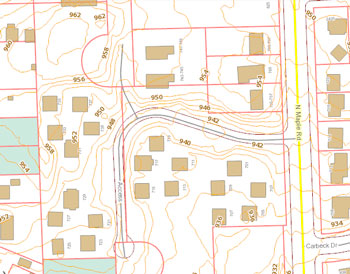

Two-foot contour map of the North Maple Estate property. The highest portion of the site is toward the north (upper left of the image), where no units were built.

She contrasted Baker Commons with units at North Maple Estates on the west side of town. The topography of the site poses challenges, and she described how many of the units have been built on the lowest part of the parcel. There are constant flooding issues, she said.

Based on a 2009 capital needs assessment, Hall estimated the capital investment gap – between what was actually needed and the amount HUD would be giving AAHC for public housing capital repairs – at around $500,000 per year. And the RAD program, with its potential for tax credit financing through privatization, is a way Hall would like to address the capital needs of most of the properties all in “one go.”

North Maple Estates was a touchstone for Ward 3 councilmember Stephen Kunselman’s remarks toward the end of the work session on the housing commission. He grew up on the west side of town, and had friends who lived in the project – which consists of 20 4-5 bedroom detached single-family units, built in 1969. He allowed that he was a little bit “nostalgic,” but noted that the families who lived in North Maple were families he grew up with.

Responding to Hall’s estimated $500,000 annual capital needs for all of the commission’s public housing units, Kunselman contended that much of that was for shorter-term needs, like appliances and boilers. So he wanted to make sure that any solution to cover that funding gap was longer-term – because appliances might need to be replaced again in 10 years. He was concerned that the housing commission might find itself in exactly the same situation 10 years from now.

Kunselman concluded that he would not support the transfer of deeds from the city to the housing commission so that a private entity could become the majority owner of the properties. Kunselman was also not supportive of transferring housing commission employees to the new private entity. When the council is asked to approve the transfer, Kunselman said, “I will say no.”

While other councilmembers expressed concerns and had questions, their outlook was more positive than Kunselman’s. Sabra Briere (Ward 1) allowed that Kunselman is right – it’s all about the people who actually live in the housing commission’s units. But she didn’t want to rule anything out until the council gets to the point of making a determination. She’d look at it with a level of optimism and skepticism.

Christopher Taylor (Ward 3) allowed that there was a certain amount of risk, but he looked at the potential for an “eight-figure” reward. He characterized the approach recommended by Hall as a “hard restart” which the city should consider investigating.

More Background on the Conversion

By way of general background, public housing is supported with government funding – primarily at the federal level – and owned by local government entities. The city of Ann Arbor actually owns the units administered by the Ann Arbor Housing Commission. From the city ordinance establishing the Ann Arbor Housing Commission [emphasis added]:

All deeds, mortgages, contracts, leases, purchases, or other agreements regarding real property which is or may be put under the control of the housing commission, including agreements to acquire or dispose of real property, shall be approved and executed in the name of the City of Ann Arbor. The Ann Arbor City Council may, by resolution, decide to convey or assign to the housing commission any rights of the city to a particular property owned by the City of Ann Arbor which is under the control of the housing commission and such resolution shall authorize the City Administrator, Mayor and Clerk to take all action necessary to effect such conveyance or assignment.

Another kind of government-subsidized housing (Section 8 vouchers) supports individuals who qualify based on their household income. Residents use those vouchers to help pay for private rental housing of their choice. Locally, AAHC manages the Section 8 voucher program for Washtenaw, Monroe, and western Wayne counties. AAHC also manages the public housing units in Ann Arbor.

In her presentation to the council on Feb. 11, Hall explained that a year ago the AAHC had 1,298 vouchers under contract, with a goal to have 1,378 under contract by December 2012. That goal was exceeded, as 1,420 vouchers are under contract as of January 2013.

To a more limited degree, HUD also provides project-based vouchers. For example, the AAHC has an allocation of 37 vouchers that are tied to specific projects, including 20 for the nonprofit Avalon Housing’s Pear Street apartment complex and 12 for assisted living in units managed by Area Agency on Aging 1-B.

Part of the reason Hall would like to convert AAHC’s public housing to project-based vouchers is due to a policy shift by HUD – away from public housing and toward voucher programs.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Voucher programs versus public housing programs. Over the last three years, HUD voucher programs (blue) have shown an increasing funding trend compared to public housing (red). Voucher programs are also funded at a much higher level overall – $28.2 billion compared to $5.8 billion in 2012.

The RAD program, which Hall was proposing to the council on Feb. 11, uses the project-based-voucher approach, but also allows entities like the AAHC to partner with private-sector developers on housing projects – something the AAHC currently can’t do.

Overall, Hall sees HUD as more committed to the voucher-based approach in the future, which would provide AAHC with a more reliable funding source for ongoing operations.

But the RAD project-based-voucher approach also allows public housing entities to tap private investment for needed capital improvements on existing public housing – by converting current public housing units into units that are owned by a public/private partnership.

Based on a 2009 capital needs assessment, Ann Arbor’s public housing stock would need about $40,000 per unit in repairs and renovations over the next 15 years. But based on current funding levels for public housing, HUD would provide only about $18,000 per unit over that period – or possibly less. The gap works out to $22,000 per unit. For the AAHC’s 360 units, that’s $8 million over the next 15 years, or in round numbers, about $500,000 a year.

Hall’s plan is to seek a range of financing in connection with the RAD conversion. But the main source is likely to be low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC), awarded through the Michigan State Housing Development Authority (MSHDA). Tax credits are awarded for projects, and are in turn sold to investors who provide funding for construction or renovation. Depending on market conditions and other factors, pricing for those credits could range from roughly 85-95 cents on the dollar. From a recent report by the Congressional Research Service:

Typically, investors do not expect the project to produce income. Instead, investors look to the credits, which will be used to offset their income tax liabilities, as their return on investment. The return investors receive is determined in part by the market price of the tax credits. The market price of tax credits fluctuates, but in normal economic conditions the price typically ranges from the mid-$0.80s to low-$0.90s per $1.00 tax credit. The larger the difference between the market price of the credits and their face value ($1.00), the larger the return to investors [.pdf of "An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit" from the Congressional Research Service.]

These are the Ann Arbor public housing properties being considered for conversion, that were included in AAHC’s RAD application:

- Baker Commons: 64 one-bedroom units

- Green Baxter Court: 24 townhomes with a total of 65 bedrooms

- Hikone: 30 townhomes with a total of 82 bedrooms

- Lower Platt: 4 houses, each with 5 bedrooms

- Miller Manor: 104 units with a total of 108 bedrooms

- Evelyn Court: one single-family home with three bedrooms

- Garden Circle: one single-family home with three bedrooms

- Maple Meadows: 30 townhomes with a total of 82 bedrooms

- North Maple Estates: 20 single-family homes with a total of 85 bedrooms

- North Maple duplexes: Two three-bedroom duplexes, for a total of 12 bedrooms

In addition to choosing Norstar Development USA as a co-developer, AAHC has already completed several other steps needed for the RAD initiative. Three entities have been hired as consultants to help handle various aspects of the process. Avalon Housing, a local nonprofit that focuses on supportive services for affordable housing, was hired as a consultant to take the lead in applying for low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC). [.pdf of Avalon Housing contract] The AAHC had originally hoped to apply for a February round of credits, but given the short timeline, has decided to wait until the August round.

From left: Ann Arbor Housing Commission board members Ron Woods and Christopher Geer attended the city council work session on Feb. 11. Other board members are Leigh Greden, Marta Manildi and Gloria Black.

Also acting as a consultant is Tom Davis of Recap Real Estate Advisors. [.pdf of Recap Real Estate Advisors contract] Davis will provide advice about compliance with HUD regulations as well as financial transactions that AAHC might pursue, including the application for low-income housing tax credits.

AAHC will also be getting help with this transition from Rochelle Lento, an attorney with Dykema who specializes in LIHTC deals. [.pdf of Dykema contract] Lento has already been working with AAHC on a pro bono basis, and assisted with changes to bylaws and articles of incorporation for an AAHC nonprofit subsidiary – the Ann Arbor Housing Development Corp. – which will serve as the entity that enters into partnerships for these RAD projects. Those changes were approved by the AAHC board at its Nov. 14, 2012 meeting.

Council Questions: Highlights

At the Feb. 11 work session, councilmembers had a number of questions and concerns. Here are some highlights.

Council Questions: Norstar?

Sally Petersen (Ward 2) asked about Norstar Development USA – the co-developer that AAHC has selected: What’s in it for them? Hall explained that Norstar’s business is doing housing development. Norstar does its own housing development, but also hires itself out – just like an architect or an engineer would – to do projects. Norstar’s staff would share the developer fee, and get paid to do the work of putting the project together, Hall explained.

Norstar gets paid to hire architects and engineers, complete the due diligence, and oversee construction. “They’re a developer – that’s their business,” Hall explained. Norstar has expressed to the Ann Arbor Housing Commission that they’re not necessarily interested in being involved for the full 15-year period imposed by the IRS compliance for affordability of the housing units involved in this type of deal. The deal could be structured in a way for Norstar to exit sooner than 15 years.

Hall explained that Norstar’s business is more on the development side, as opposed to the property management side. Norstar has a property management company that it works with, but that company is not a part of Norstar, Hall told the council.

Council Questions: Why Now?

Petersen noted that the LIHTC-type of financing that would be used has been around since 1986. She asked Hall to give two or three reasons why Ann Arbor should do this now?

Hall cited the opportunity provided through the RAD program as the main reason for acting now. Through RAD, Hall explained, HUD is promising new, additional project-based vouchers to be attached to the AAHC units. “That’s the number one reason to do it,” Hall said.

Council Question: Pre-development Funds?

Sumi Kailasapathy (Ward 1) asked Hall about the estimated pre-development costs of around $100,000-$200,000. That would cover all the due diligence. Kailasapathy wanted to know how that cost would be covered.

Hall explained that HUD will allow the AAHC to take the first $100,000 out of its own budget. The rest is being negotiated with Norstar, Hall said. Normally, the developer would pick up those costs as risk, as part of the deal. So that’s all being negotiated right now, Hall said.

Hall also told the council that AAHC would be applying for pre-development funds from grant sources. But Hall confirmed that the first $100,000 would be coming out of AAHC’s existing budget.

Council Question: All or Just Some Units?

Christopher Taylor (Ward 3) wanted to confirm that all of AAHC’s units would be included in the proposal. Hall indicated that was right, but noted that it would likely happen in two phases.

AAHC was approved for around 280 units in its initial application, she said. Now that the developer, the architect and the contractor have looked at the housing commission’s properties, they have some different ideas about the properties in the initial application. So AAHC has talked to HUD about modifying or amending its initial application.

AAHC is looking at a rehab package for the first phase. For the second phase, there’s consideration of some demolition and new construction. But that’s too much work to undertake right now, Hall said, so there would likely be an application for a second phase next year.

Council Question: Big Deal? Promises?

Taylor asked Hall how big a reset this would be, if this all works out. “Gigantic,” Hall answered. “There is no other way to reinvest and keep these units in the condition they need, unless the city puts a significant chunk of funding in every single year. I don’t know how we would do it.”

Taylor followed up by asking Hall what gave her confidence that HUD’s promise of increases to this type of voucher program would be kept.

Hall told Taylor that she personally attaches skepticism to everything that HUD does, but she said she didn’t know how HUD would get out of the contract. Rochelle Lento, an attorney with Dykema who specializes in LIHTC deals, clarified that when HUD assigns the project-based vouchers with AAHC, they’ll enter into a 15-20 year HAP (housing assistance payment) contract, and that will be binding on HUD. Like any federal grant contract, she said, it’s going to say that it’s subject to appropriations. But the federal voucher program (HAP) has been much more stable over the last 15-20 years than the public housing program, Lento said.

Part of the mentality for HUD, Lento added, is to “get out of the public housing business,” and through the voucher program to have the private sector shoulder some of the responsibility.

Council Question: Risk?

During back-and-forth between Kunselman, Hall, and Lento, Lento was asked to identify the risk to the city. She indicated that the primary risk would be if the property were to be poorly managed and deteriorated. But the city has some control over that, she said, because “you are the management company.”

The other risk she described is if the construction and rehabilitation work is not completed in a timely fashion. The key to that, she said, is having a good general contractor.

Council Question: Tax Credits?

Taylor wanted to know how the tax credit investment made by some entity with a tax liability achieves the privatization goal. Lento told Taylor this was achieved in two ways. One way is that the private investor would necessarily be involved in the due diligence, making sure that the projects actually get constructed or rehabbed. As part of the ownership group for 15 years, she continued, the investor monitors and oversees the project to make sure they’re well-managed and well-maintained.

Taylor ventured that the participation of a tax credit investor in the ownership group is not as a silent partner. Lento indicated that the investor would require regular reporting, for example on the status of the tenant population. Especially for the first 10 years, if the property is not maintained as affordable within all the provisions of the IRS tax code, the tax credits could be jeopardized.

Taylor summarized his understanding of the situation by saying that HUD is getting the benefit of third-party oversight – which is incentivized by linking the tax credits to compliance with the IRS regulations.

Council Question: Why Not Avalon? Philosophy?

Given the complexity of RAD, and given the track record of local affordable housing developer Avalon Housing, Kunselman wanted to know why the city wouldn’t just sell the AAHC properties to Avalon. Lento explained that Avalon can’t take advantage of the RAD program in the same way that the AAHC can. The RAD program is only available to housing authorities, she said.

Hall clarified that there are two parts of the equation. There’s the operating subsidy, which is tied to the vouchers. And then there’s the low-income housing tax credit investment. Avalon could go out and get tax credits, Hall allowed, but Avalon would not have the ability to have the project-based rent subsidy in the same way that AAHC can.

However, Hall allowed that Avalon might be able to make it work.

Kunselman alluded to the fact that Avalon had not been able to bring the Near North affordable housing project to fruition. He concluded that there was, in fact, a lot of risk associated with developing affordable housing.

Lento pointed out that LIHTC was the most successful approach to developing affordable housing nationwide. Kunselman wanted to know how many affordable units LIHTC had generated in Ann Arbor. Ann Arbor is more challenging because of land acquisition, Lento said. Kunselman ventured that the only reason Hall’s proposal is feasible is that the land cost is zero – because it’s public land being turned over.

Lento didn’t necessarily agree that it’s “free land,” but Kunselman insisted that it’s “land that the city owns, land that the city bought – it’s public land.” That’s what makes him skittish, he said, because the city would be losing a lot of control. But he allowed that it’s a philosophical issue.

On a philosophical level, Hall ventured that it might be best to have the property owned by a nonprofit whose goal and mission is to be an affordable housing owner – as opposed to the city. As an example, she gave the former Y site at Fifth and William, which the city acquired from the Y. For a short time, the city operated the 100 units of affordable housing there. Then the building was condemned and eventually demolished, but new affordable housing has not been developed there. Views on all this change, Hall said.

Council Question: Where to Locate Affordable Housing?

Marcia Higgins (Ward 4) took up the issue of the old Y lot. She described it as a poorly-used site, with deplorable conditions. She said everyone seems to forget about that part. She also contended that since that time, the city has learned that putting all the needed supportive housing in the middle of downtown is probably not the most efficient use of funding.

Higgins said the alternative that Hall was presenting was very interesting, and she wished this had been presented sooner. She praised Hall for taking the initiative and appreciated Hall’s hard work. Margie Teal (Ward 4) joined Higgins in expressing her thanks to Hall, and to the AAHC board.

Speaking to the issue of where to locate affordable housing, mayor John Hieftje indicated agreement with Higgins’ position that a large installation like the former Y building should not be located in the downtown. He described downtown Ann Arbor as bearing most of the burden of homelessness in Washtenaw County. To single out the downtown of the largest city in the county seemed unfair to him. The fact is that the clientele of the Delonis Center shelter comes from across Washtenaw County and beyond, he said. So it might be wiser to keep from concentrating that population in the downtown area.

Hieftje noted there was some sentiment on the city council to put the former Y site on the market and sell it. [It's currently used as a surface parking lot, as part of Ann Arbor's public parking system. A resolution, sponsored by Hieftje and Kunselman, is on the March 4, 2013 city council agenda to direct the city administrator to issue an RFP for brokerage services to sell the parcel.] If there were funds left over from the sale of that property, some of it could be put toward affordable housing, Hieftje said.

Hieftje told Hall he appreciated her creativity.

Addressing the appropriate location of affordable housing, Sally Petersen (Ward 2) spoke from her perspective serving on the city’s disabilities commission. She didn’t want the city to become a place where it’s not possible for disabled and elderly people to live downtown.

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public bodies like the Ann Arbor city council. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

This proposal makes me uneasy for reasons I can’t fully articulate. I can only hope that council gives the proposal full scrutiny and asks a number of questions before jumping off the cliff.

A couple of immediate points:

1. It is my impression that LIHTC credits are only “good” for 15 years, after which properties may revert to market-rate. How would that affect these?

2. In looking at the state site on LIHTC, I find that such properties are subject to a “subsidy-layering review”. This is intended to prevent multiple subsidies from adding up to an “over-subsidized” condition. It looks to me as though we are talking several different subsidies here. If the SLR so indicates, then one or more of the subsidies may be reduced.

Perhaps Council could ask the proposers to put together a mock example of how the different subsidies would be applied. I’d like to see an example transaction walked through all the way to see how money would change hands.

Affordable housing finance is a rather arcane discipline and we are fortunate to have such an experienced practitioner as Jennifer Hall on board. Still, I’d like to know what trends in financing at the Federal level are looking like. We have a rather unstable Federal funding picture right now and this looks like a really good area for Congress to seek savings.

I have something of an allergic reaction to any “public-private” arrangement, especially one that involves a for-profit entity. The likelihood that the public partner may end up with an unanticipated liability seems strong. Maybe it is just my hives talking. The bottom line is that I hate to see our public housing endangered at any level of probability.

Re: [1] “It is my impression that LIHTC credits are only “good” for 15 years, after which properties may revert to market-rate. How would that affect these?”

From the written FAQ that accompanied the presentation:

Today’s New York Times discusses the impact of “sequester” funding cuts on housing programs. [link] It indicates that housing vouchers are especially vulnerable.

This is no time to be changing horses.