In the Archives: Last Train to Carp-ville

Berlin-born Sonoma, California aquapreneur Julius Poppe chaperoned his group of 83 passengers on board a steamer moored in Bremen, Germany. The 12-day journey to New York that summer of 1872 proved deadly. After arrival and a two-day quarantine, only 8 of Poppe’s charges survived.

Poppe settled them onto a train. The Transcontinental Railroad linking the West Coast to Iowa and the eastern rail network had been completed only three years earlier. Despite Poppe’s best efforts for those in his care, two more died in San Francisco, and another died on the boat from San Francisco to the coast near Sonoma.

Five had survived the nearly 7,000-mile journey – only the youngest, each about the size of a pen. Poppe placed them in his pond that August, hoping for their survival.

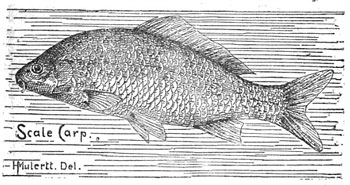

By the following May, the five German carp, also known as scale or common carp, had spawned 3,000 young. They also helped spawn a short-lived nationwide carp craze. In Michigan, state fish officials’ initial enthusiasm turned to alarm as the non-native’s depredations became another one of the state’s late 19th-century ecological disasters.

Poppe sold carp for food and for breeding to his neighbors as well as to Honolulu and Central America. News of his successful venture spread.

U.S. Fish Commission

The U.S. Fish Commission had been created the previous year in order to investigate “the causes of decrease in the supply of useful food-fishes of the United States, and of the various factors entering into the problem; and the determination and employment of such active measures as may seem best calculated to stock or restock the waters of the rivers, lakes and the sea.”

In the commission’s 1872-73 report, commissioner Spencer Baird noted:

Sufficient attention has not been paid in the United States to the introduction of the European carp as a food fish, and yet it is quite safe to say that there is no other species that promises so great a return in limited waters. It has the pre-eminent advantage over such fish as the black bass, trout, grayling, &c., that it is a vegetable feeder, and, although not disdaining animal matters, can thrive very well on aquatic vegetation alone. On this account it can be kept in tanks, small ponds, &c., and a very much larger weight obtained, without expense, than in the case of the other kinds indicated. It is on this account that its culture has been continued for centuries. It is also a mistake to compare the flesh with that of the ordinary cyprinidae of the United States, such as suckers, chubs, and the like, the flesh of the genuine carp (Cyprinus carpio) being firm, flaky, and in some varieties almost equal to the European trout.

The “genuine” carp encompassed three varieties: the mirror carp, the leather carp, and most commonly, the German carp. The federal fish commission imported carp from Germany in 1877. Some were placed in Baltimore ponds, and others in the Babcock Lakes, a series of ponds adjoining the Washington Monument before the creation of the National Mall. In 1879, over 12,000 federal carp were taken from both sites and distributed to various states and territories, likely including Michigan.

In subsequent reports Baird listed the admirable qualities of carp: they were fecund, hardy, adaptable, and had rapid growth. Carp also showed a “harmlessness in its relation to other fishes,” the “ability to populate waters to their greatest extent,” and “good table qualities.”

By 1870, Michigan fish populations had declined as a result of overfishing, dam construction, pollution, and such habitat destruction as that caused by the timber industry. The waterborne transport of thousands of logs often scarred and eroded riverbanks, Sawmill sawdust dumped into waterways could blanket and choke a fish feeding or breeding ground.

Michigan Board of Fish Commissioners

The Michigan Board of Fish Commissioners formed in the spring of 1873. It did not have regulatory power. The Board could not compel commercial fishermen on Lake Michigan to stop decreasing the size of the holes in their nets, a strategy that led to the capture of immature whitefish before they could breed. The Board could not change timber industry practices. Its strategy was to hatch and distribute fish – those used for food – to replenish depleted populations and introduce new varieties thought beneficial.

The Board opened the state’s first hatchery in Pokagon, Cass County, in 1873. The following year, the hatchery produced whitefish, Atlantic salmon, king salmon, and carp. Aside from restocking commercial fishing areas in the Great Lakes – most notably the lucrative whitefish fishing grounds – the Board also offered shipments of young fish to farmers around the state. Originally the shipments were made in ordinary milk cans loaded on trains.

Railroading Carp

In 1888 the Board secured a specialized railroad car, the Attikumaig (an Ojibwe word meaning “whitefish.”) It combined space to transport fish, five sleeping berths for the men looking after them, a kitchen, and an office. The car traveled between 20 and 30,000 miles per year between February and July, distributing trout, whitefish, black bass, pike, and carp. It was eventually rebuilt and renamed the Fontinalis. Another fish car, the Wolverine, was built in 1913; a replica can be seen at the Oden fish hatchery in Alanson, Emmet county.

Carp were on the Attikumaig for a reason. “Several marked advantages are claimed for the German carp for profitable cultivation,” noted A December, 1880 issue of the Marshall Daily Chronicle. The article continued:

Any kind of a pond, no matter how restricted, can be used. Difficulties of temperature or purity of water are scarcely factors in carp culture. Providing the water is not too cold, carp thrive rapidly. In fact, no natural water has yet been found too warm for them. Being vegetable feeders, carp thrive on plants growing in the water, or may be given offal, like pigs, or boiled grain, like chickens. A large pond may be dug on arable land, allowed to grow carp for two or three years, the fish marketed and the ground brought under cultivation again.

In the same month and year the Kalamazoo Telegraph chimed in. “The farmers of Michigan should prepare ponds for the German carp which the fish commission is introducing into this country. It is one of the most prolific of fishes and among the best that can be supplied to the table.”

The table was a big one at the 1887 annual dinner of the American Carp Culture Association, based in Philadelphia. The group’s secretary noted:

“The caterer carried out our instructions to the letter, and the result was that a select party of acknowledged epicures not only tasted but ate several pounds of carp without condiments or seasoning of any description whatever. The verdict seemed to be unanimous that carp raised and treated according to the system prevailing in this region is a first-class food fish … their flavor will be second only to the salmon family, certainly fully equal to the far-famed shad …

Perhaps the most enthusiastic carp-booster was Alliance, Ohio editor and publisher Lambelis Logan (he preferred the abbreviation “L. B. Logan.”) Logan was editor of the monthly magazine “American Carp Culture,” published from 1884 to 1888. Chapter 3 of Logan’s 1888 book “Practical Carp Culture” was titled “The Economic, Philosophic, Patriotic, and Sanitary Reasons for Carp Culture.” The chapter trails off before probing the connection between patriotism and carp, but it does extol the benefits of having a farm pond.

Aside from raising carp, “water farming,” wrote Logan, provides beneficial vapors that “will moisten and purify the air, destroy disease germs and contribute to better health.” The pond supplies emergency water during a drought, he added, gives beauty to the farm, and provides a place to bathe, to ice-skate, and to harvest ice for the ice-house.

Logan went on to detail the multiple-pond system used in European carp culture, including the hatching pond, the stock pond for older carp, and the market pond for mature fish. A series of carp ponds was a feature, for example, of a Cisterian Catholic monastery, founded in 1186, in Reinfeld, a German town in the northern state of Schleswig-Holstein. The Reinfeld town crest displays a carp to this day. Though the abbey was destroyed in the sixteenth century, the carp-ponds once tended by monks are still visible.

Reinfeld was the town that Julius Poppe had visited in 1872. He procured his fish from a town miller and carp culturist. Poppe had left Sonoma on May 3, 1872, traveled through the Panama Canal to New York, and crossed the Atlantic twice and the entire American continent once on an expensive three-month journey. He had faith in German-raised carp. Europe had had centuries to refine the art of breeding and maintaining carp in a controlled series of ponds.

Michigan farmers would have to learn on the fly.

“A method of systematic carp culture in a series of proportioned ponds as detailed in the preceding pages would be entirely too extensive and costly a luxury for beginners, as most farmers must be,” wrote Logan in “Practical Carp Culture.” “… [In this case,] a single pond must answer all the purposes.”

Leon Cole agreed in his 1905 book “German Carp in the United States.” “With a few possible exceptions carp culture has never been attempted in this country after the lines which it is carried on so extensively in Germany,” he wrote. “[Most carp culturists] merely dumped the fish into any body of water that was convenient, or into any pond that could be hastily scraped out or constructed by damming some small stream, and thereafter left them to shift for themselves . . . “

Cole was a 1901 graduate of the University of Michigan. As a junior, he already worked for the school as a zoological assistant, living nearby at 703 Church Street. After receiving his bachelor’s, he stayed on at the university to conduct zoological research, some involving carp that he maintained in an aquarium. Cole later received his doctorate from Harvard and became a zoologist and professor of genetics at the University of Wisconsin.

Carp Falls out of Favor

By the time Cole graduated, carp had already fallen out of favor in Michigan. Their habit of eating by slurping up tidbits on the bottom of a river or pond and spitting out detritus made the water turbid. Such native predator fish as the pike had difficulty seeing prey through haze. In feeding, carp dislodged or damaged aquatic vegetation, a food source for some waterfowl and shelter for other fishes. They could cause riverbank erosion in scouring for food. Sportsmen suspected that they were crowding out more desirable fish. By the turn of the century, the carp’s reputation was in tatters.

The Jan. 1, 1897 Marshall Daily Chronicle said, “German carp are becoming more numerous in the Kalamazoo river each season, and it is feared that they will sooner or later drive out all other species of fish. There should be no restriction placed on their destruction. They bring but two cents a pound in the market.”

“Some years ago the cries went up all over Michigan that the German carp be planted in our rivers,” wrote the August 24, 1899 Benton Harbor Daily Palladium. “Now that we have them the lovers of game fish are wishing they could be exterminated, for it is said that they are destroying the spawn of our best river fish, and that they themselves are scarcely fit to eat. Carp are depopulating the Kalamazoo River of its best fish.”

In “German Carp in the United States,” Cole summarized possible reasons why carp culture had failed. People had rushed into the venture without knowledge of the procedures involved. They ate carp during the spring spawning season, when the flesh was of poor quality. It was cooked incorrectly, without the European techniques that rendered it palatable. Finally, escaped carp became so numerous in waterways that it wasn’t necessary to maintain a private pond.

Carp Compared to Sturgeon

The story of carp in Michigan is roughly a mirror image of the history of Michigan sturgeon. The sturgeon is indigenous; the carp is invasive. The sturgeon needs many years to mature before breeding; the carp is fertile at a young age. The sturgeon was originally regarded as a trash fish and later as extremely valuable due to its eggs, made into caviar. The carp arrived in this country lauded by government fish experts and is now considered a trash fish.

The sturgeon’s decline and the carp’s ascent crossed paths in the 1880s. The 1887-88 Michigan Fish Commission report notes that there is “an increasing demand for carp” – there were 3,485 applicants for state hatchery carp in 1886 alone. In addition, between 1880 and 1890, over 50,000 federal carp had been planted in Michigan waters. The state report also noted “one of the most valuable fish is the worthless sturgeon of a few years ago, and so assiduously is it sought for that the supply will become exhausted in a very short time …”

Not so the carp. As a speaker at the 1901 meeting of the American Fisheries Society said, “We hear a great deal from sportsmen’s clubs and from other sources as to how the carp can be exterminated. It cannot be exterminated. It is like the English sparrow; it is here to stay.”

Mystery Artifact

In the last column, I stupidly neglected to obscure the patent number on the patent drawing of the mystery artifact.

Commenters (adept Internet-scourers all!) wrestled with the moral dilemma this posed, but proved honorable of course – no one spilled the beans!

That means I have the pleasure – it is was shepherd’s crook invented in 1884 by one Sumner D. Felt of Jackson, Michigan.

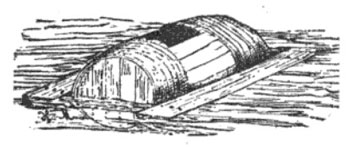

Because this column’s Mystery Artifact is about as obscure as a Mystery Artifact could be, I feel bound to drop a hint. This is something you could use in conjunction with the carp pond on your farm, in order to protect your investment. I look forward to your guesses!

Laura Bien is the author of “Hidden Ypsilanti” and “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives.” Contact Laura at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to keep readers up to date on historic aquapreneurian adventures. If you’re already supporting The Chronicle, please encourage your friends, neighbors and coworkers to do the same. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle.

It floats in a pond and newly arrived carp-lets go inside to keep them safe.

Fritz: It does float in a pond, and it is meant to protect carp, but not in that way. Good guess, though!

It looks like it might be something you float on the pond so that, in winter when the pond is snowed/frozen over, you have a place through which to feed your fish.

Timothy: That is a really great guess. Some carp cuthorities recommended poking holes in the ice, others recommended that you let the pond freeze over but make it deep–at least ten or twelve feet; the water at the bottom is slightly warmer, supposedly. Still others recommended putting in elaborate vent pipes that were said to add oxygen to the water…others said vent pipes were useless…all of these assertions were made with the kind of confident authority that betrays a complete lack of knowledge. :)

*authorities, oops.

Fill it up with birdfeed and dead fish so birds don’t hunt the carp?

Lots of great info in here, btw. Thanks for sharing.

Hi Dan, thank you for your nice comment. I love digging through these old documents.

Yours is the closest guess thus far…

Looks like a turtle trap to me…

A feedstock container for the automatic feeding of carp in the winter months?

Tim: That’s definitely getting closer! This is for something that might bore through one’s home-made earthen pond-dam…

By bear: From what I read, most home carp farmers did not feed the carp at all throughout the winter, if they were using artificial feed. Carp do slow down in movement and feeding, but they are still awake throughout the winter. They can store fat from protein-rich food sources eaten earlier in the year and to some degree subsist on that, as well as what few food bits they might find in the winter.

“This is for something that might bore through one’s home-made earthen pond-dam…”

Beaver trap?

Timothy: I’m hearing a lot of very good guesses…