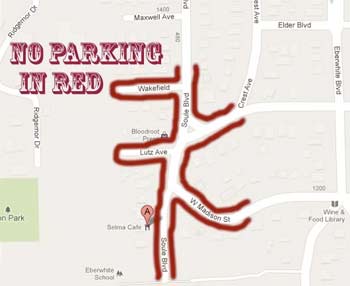

Many of the same residents who gathered at Kellogg Eye Center in late 2008 attended another meeting this month on a similar topic: The University of Michigan’s construction of a 700-space parking structure on Wall Street.

Wall Street resident Eliana Moya-Raggio, right, talks with architect Neil Martin after the April 26 meeting at the Kellogg Eye Center. The meeting focused on a University of Michigan parking structure to be built in that neighborhood. Moya-Raggio argued for the right of neighbors to be closely involved in the project's design. (Photos by the writer.)

On April 26, 2012 about 15 residents heard from UM representatives about plans for the $34 million structure, which university regents approved on April 19. The purpose of the meeting was to get input from neighbors that will inform the structure’s design. Roughly 2,000 people live in that general area.

They offered a lot of input, expressing concerns and giving specific suggestions related to noise pollution, traffic congestion, lighting and more. Ideas from residents included putting a green roof on the top of the structure, which will likely be at least 4-5 levels tall; placing the structure as far west on the site as possible, further away from residential buildings; making the structure pedestrian friendly; and encouraging the use of alternative transportation.

Tim Mortimer, president of the Riverside Park Place Condominium Association, criticized UM for a lack of leadership in its approach to parking. While UM officials like to refer to the university as the Harvard of the Midwest, he said, it’s actually more like the Southeast New Jersey Junior College of the Midwest, in terms of environmental sustainability and design. He urged the university to do more, and presented a letter from the condo association’s board that included 11 detailed suggestions for the project – ranging from architecture to entrance/exit configuration. [.pdf of Mortimer's letter]

Jim Kosteva, UM’s director of community relations, defended the university’s efforts in encouraging alternative transportation. And Tom Peterson, associate director of operations and support services for the UM Hospitals and Health Centers, provided details on a range of programs offered by UM in that regard – including vanpools, Zipcars, free bus service through MRide, and shuttle service from outlying parking lots.

But Peterson also presented the university’s case for needing more parking at the Wall Street location, pointing to employment growth at the nearby UM medical campus. Since 2009, employment at the UM medical school and hospital complex has grown from about 19,000 to nearly 21,000 employees. Even more staff will be added when a major renovation of the former Mott children’s hospital is completed, he said.

The Wall Street parking project was revived after the university pulled out of the proposed Fuller Road Station in February. The joint effort with the city of Ann Arbor would have included a 1,000-space parking structure and, some hoped, an eventual train depot. When asked about it at Thursday’s meeting, Kosteva said the university still shares the city’s vision for that Fuller Road site as a good location for intermodal transportation. When the city receives the federal support it needs for this project, he added, the university is prepared to be re-engaged about its potential role.

Kosteva was also asked about future plans for even more parking on Wall Street. He noted that the master plan for the medical center, including the Wall Street area, was approved by regents in 2005 and remains in place. The master plan anticipates adding 700,000 to 900,000 square feet of clinical and research space in the area, as well as two parking structures. That plan is guiding decision-making, he said. [.pdf of 2005 medical center master plan]

The bulk of the 90-minute meeting focused on design aspects of the Wall Street structure, in a discussion led by university planner Sue Gott. Several people pointed to the city’s Fourth & Washington parking structure as a model. Wall Street resident Elizabeth Colvin said she refers to it as the “Sue Gott parking structure,” because of Gott’s instrumental role in soliciting public input that helped shape the design. At the time, Gott worked for JJR and was a consultant on that project.

Gott, who grew up in Ann Arbor, replied by saying she knew UM had to deliver something that was worthy of this city, and something they can all be proud of. [Full Story]