Local Food for Thought

The Chronicle arrived midway through Thursday’s day-long Local Food Summit 2009, and found evidence of the morning’s work plastered all over the walls of the Matthaei Botanical Gardens conference room: Colorful sticky notes on butcher paper, categorized by topics like “Food policy/legislation,” “Resources for young/new farmers,” “Distribution,” “Heritage” and “Community Self Reliance.”

Each note listed a resource, idea or goal, and together represented hundreds of ways to strengthen and expand this region’s local food system. About 120 people had gathered to focus on that topic, and organizers hope the momentum from Thursday’s event will transform the way our community thinks about food, and in turn transform the health of residents and our local economy.

Sticky notes line the walls of the conference room at Matthaei Botanical Gardens during Thursday's Local Food Summit 2009.

The idea for the summit grew out of last fall’s HomeGrown Fest, which highlighted local farmers, restaurants using local products, and retailers selling products grown in this region. For the summit, organizers wanted to gather as many players as possible to make connections between farmers, businesses, nonprofits, educators and others interested in a sustainable food network, and to strategize about how to build on what already exists.

Part of the day was devoted to speakers, but much of the time involved brainstorming and discussions, with the promise that organizers would synthesize the work and make it public. (If you didn’t attend but you’d like to be on the list, send an email to info@localfoodsummit.org.) Here’s a much-condensed summary of ideas generated in just a few of the categories discussed at the summit:

- Resources for young/new farmers: Form mentorship programs, start a farm incubator (modeled after the more common tech business incubators), find land and funding for new growers, hold job training for unemployed or laid-off workers focused on agriculture.

- Bringing producers and purchasers together: Hold a community forum for food sharing, provide online resources to connect growers and buyers, create a barter system for food and services, develop a local currency for local food.

- Food processing: Deregulate the food-handling system, create a local USDA-approved processing plant, get more distributors to handle local foods and get local foods into more groceries/supermarkets, create mobile food-processing units.

- Education: Teach kids how to cook/shop/eat local foods, hold a Local Food Campaign to promote locally grown products, create incentives for attending cooking or food classes, hold training on how to farm.

- Accessibility/food security: Provide more food-stamp processing machines (Electronic Bridge Transactions, or EBTs) in farmers markets and other local food retailers, expand Project Fresh, have more places to sign up for food stamps, expand the Plant a Row for the Hungry program to encourage gardeners to donate extra produce to local food banks.

- Infrastructure/systems: Create a coordinated food network, form more community gardens and community greenhouses, plant an edible park, create a transit infrastructure for transporting local food from growers to buyers.

Participants in Thursday's Local Food Summit listen to Patty Cantrell of the Michigan Land Use Institute.

Speakers for the day picked up on many of these themes. Patty Cantrell of the Michigan Land Use Institute described several initiatives that the Traverse City group is leading, including an online local food exchange, and training classes for farmers.

Ann Arbor consultant Fran Alexander gave an overview of a study on food security for low-income residents of Washtenaw County, part of a broader food security initiative led by the nonprofit Food Gatherers. To lay the groundwork, she noted that nearly 50,000 people in Washtenaw County are living in poverty, and that food pantries are needed by hundreds of households as a regular way to keep food on the table.

Residents using local food pantries were surveyed in August 2008. Some of the findings include: only 12% said they eat five or more servings of fruits and vegetables a day – people who didn’t said it was too expensive; 45.3% said they use the food pantry as a supplemental source of food on a regular basis, not just in an emergency; 41% of food pantries said they either usually don’t or never have fresh produce, a situation dubbed “canned compassion” by food activist Mark Winne.

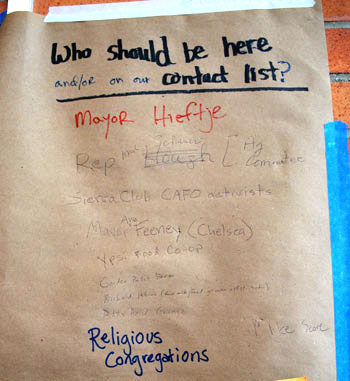

A list of people and groups that those attending the Local Food Summit thought should be involved in future efforts.

Strategies for dealing with a crisis in food security include increasing advocacy and increasing the procurement of healthy foods, with a focus on local sources. In that latter category, the Food Gatherers board of directors is pursuing the idea of buying or leasing a local farm to produce food specifically for distribution to low-income households – they discussed it at their last board meeting, Alexander said. The full report of all these findings and strategies will be posted on the Food Gatherers website by the end of February.

The day’s final speaker was Chris Bedford, president of the Center for Economic Security. He told the group that our country is in a crisis of over-consumption, of spirit and of trust. It’s imperative that we “re-localize” our economy, he said, especially in the areas of food, finance and energy. It’s all about economic renewal and community resilience – if we’re to survive, he said, we need to “trust each other, know each other, work with each other and love each other in our communities.”

Bedford described some initiatives in the Muskegon area aiming to do just that, with a major focus on getting local food into the school system. But the challenges are many, including a federal commodity program that subsidizes megafarms to produce food for schools, and liability exposure that would cripple small growers if they were sued over food contamination. School boards – and thus, the community – have power to influence decisions, Bedford said. Muskegon Heights schools, for example, contract with Chartwells (which also holds a contract for Ann Arbor schools). Bedford believes that Chartwells is “scared witless” about the local food movement.

Bedford said neither the federal nor state governments support local food initiatives, and noted that the industrial food system is endorsed by Jim Byrum, the powerful president of the Michigan Agri-Business Association and an ally of Gov. Jennifer Granholm. Yet Bedford believes there’s a chance to change Michigan’s food policy, and that the 2010 elections will be crucial in that regard: “We need to at least bring up food policy in these elections.”

Someone in the audience asked Bedford how having a local currency might help develop a local food system. Bedford said it keeps money in the community, and also brands the community – he pointed people to the example of BerkShares, which is currency used in the Berkshire region of Massachusetts. He held up a $10 BerkShares bill, with images of turnips on one side and on the other a picture of Robyn Van En, who started the country’s first community supported agriculture (CSA) project. [The Chronicle knows of only one group in the Ann Arbor area that has its own currency: The Dexter-Miller Community Co-op. If there are others, we'd be interested in hearing about it.]

Bedford is also a filmmaker, and is working on a new film about reinventing the local economy. Ann Arborite Jeff McCabe, who attended Thursday’s summit, is hosting a breakfast at his home on Feb. 15 to raise funds for the film. Details on the event – called Diner for a Day – are online here. [confirm date]

The day ended with small group work, organized by categories that had been determined in the morning’s brainstorming session. The idea is that the people in these groups will determine next steps, which will later be communicated with other summit participants and the general public. Amanda Edmonds of Growing Hope urged participants to keep the topic of accessibility, justice and food security top of mind, noting it was an issue that crossed all categories. [Earlier in the day, someone had noted that the summit wasn't as racially and socioeconomically diverse as it needed to be, and that those voices should be part of the local food system.]

Though many ideas being hatched at the summit are in the embryonic stage, one concrete effort is already being planned: the month of September this year will be designated Local Food Month, with several events in the works.

Finally, we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention the role of food in Thursday’s summit. Zingerman’s provided coffee and bagels in the morning, and the lunch was catered by A Knife’s Work, using local ingredients:

Just before lunch, Brendan McCall of A Knife's Work talked about the compostable dishware they use, and showed people where the compost bin was located.

Food Summit Lunch Menu

- Moorish Lamb, Chickpea and Kale Stew (Cinnamon and smoked paprika spiced lamb meatballs in a cumin scented chickpea and kale stew)

- Spicy Swiss Chard, Tomato, Garlic Soup (Roasted green chili and garlic tomato broth with sauteed swiss chard and white beans)

- Roasted Butternut Squash, Pear and Red Chili Salad (Pan roasted pears and butternut squash tossed with mixed greens and dressed with a sweet red chili vinaigrette)

- Fresh Baked Cinnamon Apple Cobbler with Vanilla Creme Anglaise (Fresh baked Michigan apple cobbler with cinamon, butter and brown sugar. Served with a vanilla bean custard)

And though they generally aren’t edible (or at least, The Chronicle didn’t see anyone eating them), fresh flowers were provided by Lisa Waud of Pot & Box.

The event wrapped up at 3 p.m., but for several folks it wasn’t quite over – they were headed to Corner Brewery in Ypsilanti, where owner Rene Greff had promised a tour and, quite possibly, a few beers.

Lisa Brush of the Stewardship Network in Ann Arbor was facilitator for the Local Food Summit. In the background is Shannon Brines of Brines Farms, one of the organizers.

Amanda Edmonds of Growing Hope talks with Chris Bedford, left, and others attending Thursday's Local Food Summit.

Thank you for the in-depth write up! As I have complained about before, I am very sad that they had this during the day when most people work. I would have liked to have been part of the conversation re: diverse voices. I can’t speak for this area, but I can tell you that in “my” part of Detroit (i.e. where I work) this is not a topic that engages people. Most lower income folks that I know are more interested in keeping their jobs and eating 3 meals a day–the idea of paying more for food just because it’s “local” is not even a consideration. My parapro and I had the Wallmart discussion last week in class, and I couldn’t argue with his logic–if you need something and it’s $3 at Wallmart but $5 some place else, you gotta go to the ‘mart.

I’m not trying to speak for all lower income folks, and I appreciate that folks want a diversity of voices, but some major changes (job security, income parity, time to devote to finding local food, availability of local foods esp. when considering that many folks don’t have transportation) will have to take place before there will be a huge shift in the dominant paradigm of people who are able to pay more for food.

Leveling the playing field to secure fair markets requires grass roots educational opportunities wherein people learn about the business of food. One reason so called discounters in retail foods appear to sell for less is the system of USDA grading standards. The term “Choice” for example, while sounding like a high quality grade, is actually a low quality grade for peppers, eggplant, and other fruits. Similarly, while the term “Select” may also appear as if it too were a quality grade, it is actually a low one for cucumbers, and beef.

But where education may provide the greatest benefits for local food consumers is in requiring the term “fresh” be legally defined. Today, the term is meaningless when Peruvian asparagus for example, spends on average 21 days on a boat, another 7-10 days in the domestic distribution chain, and is thirty days from harvest by the time it reaches a U.S. consumer. Thus, by any reasonable “standard” it is not “fresh.” Produce should be labeled with a “harvest date” not a sell-by or best-if-used-by date.

The values of flavor, nutrition, and local economic benefits to local food depends in many ways upon our understanding of the food business. At this time in the local foods movement, most consumers are clueless. And that’s exactly the way Big Food wants us to stay.

The fact remains one cannot buy what isn’t on the shelf, and local food at best is there only seasonally. But just imagine what it would mean to communities if consumers had the right to know the date when food was actually harvested, and the time gap between that harvest and when it was actually processed.

Like a poorly regulated financial sector, sooner or later a poorly regulated food industry will result in a major food crisis. History has proven human food seeking behavior is ugly. And when a major food crisis occurs, having money won’t matter too much. Knowing about who’s growing your food, how it was grown, where it was grown, and when it was harvested is the key. And raising the level of importance of food in our daily lives is a crucially important factor in food security. Knowledge is what we need to advance the movement.

Lee LaVanway, Market Master

Benton Harbor Fruit Market, Inc.

TeacherPatti brings up an uncomfortable contrast between two arms of the sustainable or local food effort: on the one hand, providing the means to make local food production a viable economic enterprise; and on the other hand, the affordability of fresh local food for lower-income people. Sometimes that is also simple accessibility. The Washtenaw County Public Health department has had an ongoing project to promote the accessibility of healthful food, backed up by good data collection (available on the ewashtenaw.org website). They have worked with the Ypsilanti Farmers’ Market to make financial assistance available (the ProjectFresh and EBTs mentioned above)and highlighted the existence of “food deserts”, where it is difficult to obtain fresh food. However, some fresh local food projects are aimed more at the artisanal/epicurean market, very nice if you can afford it. (The lunch tickets for the summit were $12, maybe not a huge sum but reflective of that very appetizing menu.)

I think that one answer to affordability of fresh local food must be full support of community gardening opportunities. I’m grateful for the work of Project Grow and also glad that the City of Ann Arbor has continued its support for the community gardens after having dropped them from the budget. I hope that the city’s support of this effort is expanded beyond mere monetary support to other forms of encouragement (the West Park garden is an encouraging start).

Thanks to Vivienne Armentrout for passing along these links – both are reports (in PDF files) from the Washtenaw County Public Health department:

1. The Human Food Habitat in Washtenaw County (2008)

2. Availability and Accessibility of Healthy Food in Ypsilanti (2007)

I think TeacherPatti rightly points out that we cannot solve the problem of access to good food until we solve the problems associated with poverty. Access to good food should be a basic human right in this country and in this agricultural state. And at the same time, farmers and other food producers deserve to make a decent living.

A big part of the reason that healthy, sustainable food is not a basic human right is that every one of us is funding cheap, unhealthy, industrial food with every tax, grocery and fast food dollar – not to mention environmental degradation, unfair working practices, and shameful animal living conditions. What are our priorities as eaters and as a nation?

Until we demand a higher standard for everyone, at a policy level (local and national), healthy sustainable food (along with better schools, neighborhoods, and other opportunities) will remain the purview of those with the resources to afford it.

We’ve already tried making food cheap – it’s cheaper in this country than in any almost any other industrialized nation. I don’t see how the tangled web of our problems gets any better by making food cheaper. How about trying paying everyone a living wage and improving our schools?

I agree with Lee – “Knowledge is what we need to advance the movement.”

As for paying for the $12 lunch for the Summit, $1.40 of that went to the online ticket service, the rest paid a local business and local farms. Scholarships for the day were extended to everyone who requested them.

What are our priorities as a community really?

I should have said Hunt Park, with reference to new gardens planned there. West Park discussions have included mention of community gardens, but I don’t know how far they have advanced.

As I said previously, local food production must be a viable economic enterprise. This is crucial to our food security. Sometimes this means that we must pay more for locally produced food than for the same type of food (it will seldom be really the “same” food) in the supermarket. Further, it is in our self-interest (each of us) to pay enough for local food production so that we do not become dependent on that very long supply chain to the West Coast and further. It is also usually better quality. I try to buy local in almost all circumstances as far as is practical and expect to pay more than rock-bottom prices.

The question is how we can also extend the availability of this food to those with less ability to pay. As Kim says, food is very cheap in this country – but much of that cheap food is industrially processed, filled with calories from high-fructose corn syrup, for example, and made with industrially grown meat. Often this cheap food is not even wholesome (note the recent peanut food poisoning problem). (I’ll just say “Michael Pollan” and let it go at that.) It would be sad to see us become a society in which access to fresh local food is limited only to the affluent, while a lesser class is condemned to fast food and over-processed or canned items.

A partial solution is to allow people to produce as much of their own food as possible. Another is to subsidize purchase of the food.

I was comfortable with paying $12 for my lunch ticket for the summit (I was not able to attend, so donated it), and it appears that it was a very good value for the meal that was served. I didn’t mean to be critical of the organizers of the summit, who clearly made a wonderful thing happen.

There should be garden plots at all local parks and schools and requirement for garden areas for all new high density housing. The fact that I need to drive my car to any of the current project grow gardens is simply backwards.

I agree cheap food is often not wholesome, but for people with lower incomes this is often all that is accessible. It’s this barrier that needs to be a central focus.

Adding to the comments by Kris (#7), a community that is truly supportive of the production and consumption of local foods should have no deed restrictions, ordinances, or stigma associated with front yard vegetable gardening (for those of us fortunate to live in neighborhoods with our own yards vs. apartments). I’d also like to know what the process would be to remove deed restrictions within Ann Arbor neighborhoods that prohibit backyard chickens in spite of the recently passed law.

Not only would I like to see local efforts to dramatically increase the use of healthy, locally grown foods for the meals served in our schools, but there should be a vegetable garden at every school plus real kitchens where kids can learn to cook. Children do learn to eat what they grow and prepare themselves. It’s a long road to building habits that lead to health. I agree with those who have stated that knowledge is key. Indeed, knowledge is power.

I’d like to hear how Agarian Adventures is doing this year. It was a school-based program aimed at Diana’s objectives.

Following up on the last two posts –

I live directly in front of Eberwhite Elementary. I have had preliminary conversations with the school regarding the addition of a school food program including a large outdoor garden and a hoop house, similar to the set up at Tappan. The principal – Debi Wagner seems quite receptive to the idea.

I would be willing to raise the money (through our repastspresentandfuture.org efforts, channeled straight to Agrarian Adventure), oversee the “dirt” aspect of the program and work with Agrarian Adventure to model the program on what they have already done.

So far, I have been directed to “talk to the PTO” which has to date been a non-starter (basically that they have other projects/priorities already and that they already have a garden). I think it would take a bigger groundswell of interest from the community to let them know that this is wanted/needed.

I also envision this as not just a project funneled through the PTO but a partnership involving the school, Agrarian Adventure, and the community/neighborhood. SELMA – the Soule-Eberwhite-Liberty-Madison Affiliation is one neighborhood group forming to fill this community role and includes Eberwhite kids as well as kids at other class levels, home-schooled kids, Steiner kids, etc.

Additionally, I know that Eberwhite is seeking “green school” status. I do not know much about this process, but hear it involves energy audits, adopting an endangered species, … I would hope that real, local food, by and for students could figure into this process.

Regarding Agrarian Adventure – I think this is exactly the type of project needed to help them jump from it’s present site, into the entire school district.

If you are willing to commit energy to this process please contact me: panchobush@gmail.com and call the school: (734) 994-1934 to let them know how important this early-start, hands-on experience is for kids.

Jeff

Thanks for the comments! I am like a one note little sheep that keeps bleating about this issue, but it really bothers/unnerves/irritates/pisses me off. I would almost love to have people come to my room and see what they feed our kids in DPS. Even the kids know it’s crap. I read the menu every day and there’s almost always at least one “Oh God…yuck!”

The sad fact is that our school district is so strapped for cash (at least a 10% pay cut next year, I’m told) that we can’t even get to discussing food issues. Personally, I LOVE the idea of a school garden, but what would happen to it in the summer? Our school isn’t in a horrible neighborhood, but we got a few CRIPS (charmingly misspelled CRIPES, with the E later crossed out) tagged over the summer. Our science teacher’s flower garden was ripped up, also.

I have a lot of hope for the Greening of Detroit and its community gardens. I heard somewhere that if the vacant land in Detroit was used for food, it would feed all the people. Why the heck can’t someone, somehow, someway make this happen???

The fairness of food is a difficult question. When I worked at Avalon Housing, I privately lamented the fact that tenants often bought and ate some of the worst food I’d ever seen. But it was what they could afford on fixed and limited incomes, and who was I to judge? Locally grown organic food was and is expensive in comparison, and when you’re talking to someone who makes even less than a local farmer (and is in no way on the verge of becoming a rock star in our culture) there is little space to argue, as TeacherPatti says.

Yet, the goal of good, fresh, accessible, quality, locally-grown food is not impossible.

Project Grow (who I volunteer for) works steadfastly and determinedly to find places for community gardens. By building partnerships throughout the community with the Parks Department, local churches and other organizations, as well as area schools (and even the airport!), the goal is to offer the opportunity to garden to anyone who wants it. Neighbors play a critical role in the creation of these spaces. None of our gardens would be possible without the voices and efforts of interested and concerned neighbors joining the chorus. It would be our greatest delight to have plots in every park and on every bit of unused lawn we could. (Just a little more horn-tooting here: We also offer classes on growing your own food – everything from the absolute basics of gardening and seed-starting to bee-keeping and hoophouse growing – to help the novice and the experienced grower alike.)

Another great example: Avalon Housing, inspired by Fritz Haeg’s Edible Estates, installed an experimental garden for tenants at one of its properties. Tentative at first, tenants quickly snapped up the available spaces and filled them with seeds and plants. Not only did the garden provide a place for tenants to interact with each other and staff, but neighbors stopped by to say hello, comment on the vegetables, and talk to the growers. Guided by a volunteer gardener, these tenants enjoyed fresh tomatoes, basil, lettuce, edible flowers, cabbage, broccoli, carrots, greens, watermelon, and more. Stories of gardening with parents and grandparents along with exclamations of wonder at what they accomplished were regular happenings. The sense of accomplishment this garden afforded these tenants and the extra bits frozen for winter use is priceless. This year Project Grow and Avalon are looking to begin a program of Supportive Gardening, too, to continue and expand this project.

Avalon also participated in a Project Grow site last year at Food Gatherer’s. This huge plot tended by one staff person and a cadre of tenants – young and old alike – raised tomatoes, peppers, herbs, greens, and a few flowers. And for a number of years Avalon has purchased shares in the Community Farm CSA, the proceeds of which are distributed to tenants who eat and preserve the food.

These are small beginnings (seeds, if you will) that lay the groundwork for the kind of change the Local Food Summit seeks to implement, and great examples to follow and expand upon.

I work as the school social worker and yoga teacher at the Washtenaw County Children’s Youth Center–our local juvenile jail. Last spring I facilitated, planted, tended and harvested a vegetable garden in one of our interior courtyards with youth in our residential substance abuse treatment program. The food we grew was used in salads and meals through out the summer and into the fall. The youth who helped really enjoyed digging in the dirt, planting the seeds, and watching as our crops developed. The building’s supervisors and administrators are supportive and open about expanding the garden into the second interior courtyard this spring, but I can’t do it all myself, and it’s difficult to get commitments for help from other staff and folks in the community. I’m currently working with the U-M School of Social Work to find an intern for the spring and summer who loves to garden and is interested in working with incarcerated youth in a high security setting, but I’m not sure if someone will choose our site. If any of you have interest in volunteering, or know others who might, please pass the info along to them. I can be reached at lgott@wash.k12.mi.us or 734.973.4485

changes to improve cost and access can be addressed through the farm bill. existing commodity supports promote over-production of a handful of crops, including subsidies for corn used for high-fructose corn syrup, one of the key ingredients allowing food manufacturers to produce “junk food” so cheaply.

and what about other policy approaches to make fresh, healthy foods more affordable? a “junk food tax” ? this revenue could be used to support access for low-income people. how about requiring WIC to provide a certain percent of calories in the form of local, organic produce?

recent farm bill legislation has received more attention and press than in the past (thanks in large part to michael pollan) and a public uproar will help shape that bill into something that will promote healthy, affordable, sustainably-produced foods.

Just to back up Kim’s point about the affordability of good food, it’s worth pointing out that much of the history of food in the past few decades in the U.S. has been a process of people finding ways to make food a little bit worse and a little bit cheaper. And, as KT points out, subsidies make some of the worst foods even cheaper. As a result, while countries like France and Germany now spend about 16% of GDP on food, we spend more like 10% of ours. (On health care, by contrast, the percentages are reversed.)

The problem is, it’s hard to make food better without making it at least a little more expensive… but increasing our food budgets by 60% isn’t an option for most of us because our other expenditures have adjusted accordingly. We need a transition back to paying farmers a fair price for good, clean, fair food, but if it’s going to work it’ll probably have to be a gradual one — perhaps even as gradual as the worsening and cheapening of food that got us to our present condition.