Column: Arbor Vinous

Two charter members of the Vinous Posse dropped by the other day, carrying a treasure from their cellar.

It wasn’t a bottle of wine. They were carefully coddling a copy of the Holiday Wine Catalog from Ann Arbor’s Village Corner – circa 1977.

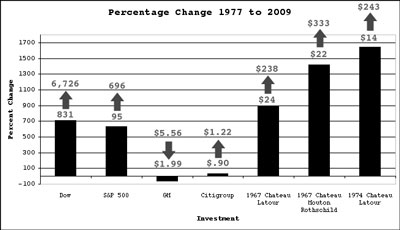

A quick flip through its pages elicited a classic “AHA!” moment: the eye-opening realization that my 401(k) might be riding significantly higher in the water if its early-on stock acquisitions consisted of Château Lafite and Château Latour, instead of GM and Citigroup.

Of course, that assumes my forbearance from indulging in too many celebratory pours out of the profits.

Like many long-term collectors of less-than-opulent means, I frequently joke that I can’t afford to drink the older wines in my cellar, let alone replace them at today’s prices. The price run-up among first-tier wines over the last 20 years has been little short of breathtaking.

But it wasn’t until I saw Village Corner’s price tag on a 1967 Château Mouton Rothschild – $21.95 – and compared it to the $600 tab on the soon-to-be-released 2006 vintage that it struck me how many years I may have been making wrong-headed investments.

A quick check-in at the wine pricing website Wine Searcher tells the story: even the two so-so vintages in the 1977 catalog, both currently well past their peak for both drinkability and price, showed price gains that handily beat the stock market during the intervening 32 years.

But if you take the trouble to store wine for 25 years, you may want to shoot for even higher returns. So I phoned Dick Scheer, Village Corner proprietor since 1970 and writer of the catalog I was browsing, for some tips about wine investing. Needless to say, he confirmed there’s more than meets the eye.

“Only a limited number of wines make a difference as investment grade,” Scheer told me.

Which ones? Primarily First Growths and a few other top Bordeaux, such as Petrus, Cheval Blanc, and La Mission Haut Brion.

My hypothetical 1967 and 1974 purchases pass the test. Both Latour and Mouton Rothschild are First Growth Bordeaux.

What about all those expensive wines on the shelves from elsewhere? They don’t make the cut for investment, according to Scheer. “Burgundy hasn’t mattered much. Neither has vintage Port. Nothing white, other than Château d’Yquem,” he advised.

The same goes for the tiny production, so-called “trophy” wines, coveted in recent years by high-end collectors. “Producers have learned that if you limit the release enough, you can sell it at almost any price. That’s the concept of the trophy wine, as distinct from investment. It’s meant to be shown off and poured. It shows my ability to buy,” Scheer said.

Vintages matter just as much as a wine’s origin. Not surprisingly, high quality, long-lived years make much better investments.

That’s where both the 1967 and 1974 Bordeaux earned failing grades; both years were mediocre at best, and entered into their terminal declines years ago. By comparison, the current price for a bottle of 1982 Mouton Rothschild – considered a top-tier vintage, still drinking wonderfully – ranges from $750 to over $1,000, several times those of adjacent lesser years.

What about the 1982 Château Latour? Figure on $1,500 and skyward for a single bottle. Not a bad return on your initial $40 investment.

So are you licking your chops, ready to grab the next top vintage that comes along and sit on it for 25 years? Not so fast, cautions Dick Scheer.

If you’d like to eventually sell the wine for top dollar, you’ll have significant overhead expenses – primarily storage and insurance. Many serious wine investors lease commercial temperature and humidity-controlled storage facilities in big cities.

Too much humidity can decay – “fox” – the labels. The wines are still perfectly good, but you’ll lose money for less-than-stellar esthetics. Too little humidity is much worse; the cork may dry out and shrink slightly, letting some wine evaporate and dropping the wine’s level in the bottle – a costly flaw in the resale market. And if you can’t document optimal storage conditions throughout the wine’s entire lifespan, it may also be worth less to some future buyer.

Want to taste just one bottle from a case and resell the rest? That’ll cost you big-time; whenever a wooden case is opened, it loses a lot of value. Or, as Dick Scheer quotes Ann Arbor collector Ron Weiser, “Never buy an eleven bottle case.”

Should people still buy wine today for investment, in hopes of 1982-style eye-popping returns?

Dick Scheer is bearish. “Investors need to know when to get in and hold back. Now is a time to hold back.”

Why? The main reason is the lack of excellent upcoming Bordeaux vintages – even 2006, with its $600 bottles of Mouton Rothschild, is merely an average-plus year. In addition, several market features have changed since the days when a small coterie of British “claret” drinkers dominated the market, buying two cases of First Growths in top vintages: one to drink and one to sell. Among the recent changes:

- The worldwide wealth explosion. “Now along come the Russians and Chinese and nouveau riche from all over the world. Latour to drink with sushi. They’re all in there bidding the prices up,” explains Dick Scheer.

- Much of the investor profits in previous decades actually came thanks to currency declines in the U.S. dollar versus the French franc. Now that Bordeaux prices are denominated in euros, that’s unlikely to continue.

- Investors formerly bought highly discounted “futures” on upcoming Bordeaux vintages, for nearly guaranteed instant profits when the wines were released. Nowadays, futures are marked up to the point where there’s little to be gained by pre-purchasing top wines.

“It’s a gamble,” concedes Dick Scheer.

So, I asked him, why invest in wine at all, compared to alternate investment opportunities?

“You can’t drink a piece of property or a bank account. The beauty is it’s a liquid asset; it’s a winning proposition because you can always drink it.”

____________________________

One final note: The front cover of Village Corner’s 1977 catalog listed the names of the store’s four wine salespeople. Dick Scheer owned the store then, as he does today. Rod Johnson worked there until last year, when he left to run the wine department at Plum Market. Ric Cerrini still sells wine at Village Corner. Only Steve Eliot departed Ann Arbor wine retail – for California, where he’s now Associate Editor of the Connoisseurs’ Guide to California Wine.

That’s a pretty amazing bunch of long-time wine professionals under a single roof – one that I doubt many local retailers, in any field, come close to matching.

About the author: Joel Goldberg, an Ann Arbor area resident, is editor of the MichWine website. His Arbor Vinous column for The Chronicle is published on the first Saturday of the month.

Excellent nostalgia piece about the VC!

I agree with Dick that the high end wines are in a bubble. Anyone want a tulip or a share of Worldcom?

Thou speaketh the truth.

The market fundamentals for top tier wines are so strong right now that investing now would be like buying Nortel in 1999.

I’ve been saying “these prices can’t last” for 15 years — during which time they’ve multiplied an additional five times or so. If it’s legitimately a bubble, it’s the longest-running one that I’ve run across.

Joel