Column: Dead Duck for Thanksgiving

At Thanksgiving, a flesh eater’s fancy turns heavily to thoughts of a dead bird. What better time of year, then, for cartoonist Jay Fosgitt to serve up a pair of them?

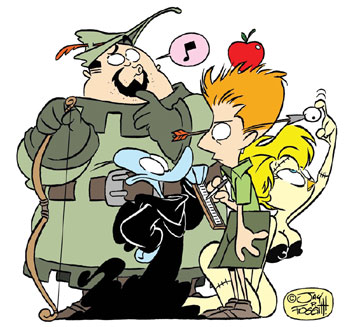

Meet Dead Duck, the title character of Fosgitt’s debut graphic novel, and his sidekick, Zombie Chick. They work for the Grim Reaper (aka J. P. Yorick); their task is to haul the reluctant chosen over to the other side (aka Rigormortitropolis) by any means necessary.

Happily for us all, bringing in the dead has always been a rich lode for historical references, literary allusions and rude humor.

“Dead Duck” takes off on all three, with riffs on the Salem witch trials, Beatlemania, the Canadian health care system, the Crusades, Punch and Judy, the “Vagina Monologues,” Chaucer, SCTV’s Doug and Bob McKenzie (Fosgitt has great affection for the Great White North), Nazi porn and blaxpliotation flicks, just to skim the colorful surface.

“Dead Duck,” Fosgitt freely advises, is “not profane, but it’s certainly not for little kids.”

The book, published by Ape Entertainment, is due out next month – though Fosgitt is expecting a FedEx delivery of 200 copies to his home today, according to his blog. The weekly comic also has been appearing since February at Apecmx.com. That’s where you’ll find Fosgitt’s commentary on his inspirations for that week’s strip and the technical aspects of cartooning, as well as other observations. And you’ll find Fosgitt at Ann Arbor’s Vault of Midnight on Main Street from 5-8 p.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 2, where he’ll talk about “Dead Duck” and sign copies of his book.

How Dead Duck Was Born

In contrast to the over-the-top energy of his cartooning style, Fosgitt is soft-spoken – but nevertheless sure of what he wants to say. He grew up about 10 minutes west of Saginaw in Shields, which at the time was “breathing its last gasp as a farming community and was gradually changing into a suburb,” he recalls.

“Without the Internet and for the most part without cable, I was left to entertain myself for the bulk of the time and I think that served me well in what I do,” Fosgitt says. “I grew up around comic strips in the newspapers. I was in a fairly rural community so we didn’t have art museums or anything like that, but the Sunday funnies were always at hand and comic books were at the local 7-Eleven.”

As a kid, Fosgitt says, he read “mostly comics or books about comics,” but he developed a wider appreciation of literature, history and mythology at Delta College and then at Central Michigan University. Fosgitt also enrolled in traditional art classes that he says “only strengthened what I was able to do in my cartooning by learning perspective, life drawing, things like that.”

Dead Duck was hatched in 1989 by the then-15-year-old Fosgitt, who had discovered “Watchmen,” a mid-1980s comics series (reissued in 1995 as a graphic novel). “I was very influenced by it,” he says of the seminal “adult” comic, which dealt with nuclear war, vigilante justice and other dark and ambiguous themes. He was particularly fascinated by the character of Dr. Manhattan (for the uninitiated, Dr. M is blue, bald and way ripped). But at some point Donald Duck literally entered the picture, Fosgitt “mashed them together” and a blue duck was born.

Dead Duck then waddled into a back seat until 2005, when Fosgitt made a stab at a comic book called “The Herd,” featuring a team of animal superheroes. “I thought, ‘I’ve got Dead Duck lying around and I’m not doing anything with him, so I’ll put him in there. And I’ll give him a sidekick.’” Enter Zombie Chick.

“But it didn’t take me long,” Fosgitt says, “to learn that, no, he worked better on his own – he worked for Death.” And the cartoonist has been working full bore on finishing “Dead Duck” since early this year.

Comic Books Versus Graphic Novels

The format of the comic book is classic and cheap: newsprint pages, garish color, thin covers. The graphic novel is thicker, printed on expensive, glossy paper. Other than production values, though, what separates the two? Initially, Fosgitt says, it was content – as reflected in the Comics Code Authority.

The comic book industry created the CCA in the early 1950s in response to the cultural panic du jour: horror comics. The self-censoring CCA seal of approval effectively wrung sex, gore and wit from the genre.

But it also gave American culture a great gift in Mad, when the comic book’s creators moved to evade CCA’s oversight by reclassifying the publication as a magazine – and forever after encouraging in its readers a similar respect for authority.

“In the old days,” Fosgitt says, “you had the Comics Code Authority and you were limited in the kinds of stories you could tell and the kind of language you could use and the visuals you could employ,” he says, “but in a graphic novel it wasn’t governed by the CCA and you could do very adult things.”

In the early ’80s, he says, Marvel Comics started publishing its own line of graphic novels and made the format “a regular thing.” And by the 1990s, Fosgitt says, the code had “dissipated” as cartoonists and publishers “finally got it into our heads that we can govern ourselves. … And we trust our audience to judge for themselves what is and isn’t appropriate for their families to read.”

A Community of Cartoonists

Fosgitt and his wife, Laura, met at CMU; they moved to Ann Arbor in July 2008 so she could work on a master’s degree in theater education at Eastern Michigan University. “Within weeks of moving here,” he says, “I became friends with a lot of other artists – a lot of cartoonists live in this area.” Dave Coverly, who creates the Speed Bump strip, helped usher Fosgitt into the National Cartoonists Society. “This town is ideal” for artists, Fosgitt says – while acknowledging the, um, challenges of Ann Arbor’s high cost of living. “This is my living,” he says, gesturing around the studio he’s set up in the second bedroom of the couple’s rental apartment. “It’s a lot of scraping by.”

Fosgitt and Ape Entertainment discovered each other in August 2007 when he brought his “Dead Duck” work to the annual Wizard World Chicago convention. “I rounded a corner and ran into Ape’s booth” and wound up showing the company rep the cartoons, he says. “They took it up and eventually we signed a contract.’’

Ape prints and ships the book; promotion is the author’s job, and it’s been what Fosgitt calls a “grassroots effort” to get the book out. He’s spent the better part of the past few months working the phone to line up pre-orders with comics sellers around the country, and says he’s found “receptive retailers.” Vault of Midnight, which is hosting the reading next week at their 219 S. Main St. store, not surprisingly has a big fan in Fosgitt. “They have such a wide and varied stock,” he says; “they cater to all sorts of comic fans.”

Next on the drawing board for Fosgitt is a follow-up to “Dead Duck,” he says. He’d also like to find a publisher for “Pillow Billy,” a children’s book he wrote and illustrated, but “my mind and heart are still very much with Dead Duck.”

More from an Interview with Jay Fosgitt

Early encouragement, and heartbreak: When Fosgitt was 10 he wrote a fan letter to Jim Henson. The creator of the Muppets wrote him back, a few more letters were exchanged. “He wanted me to come see him when I graduated from high school because he liked my artwork and wanted to talk to me about working for his company.” Henson died in 1990, when Fosgitt was a freshman. “That was devastating.”

Best education he got in cartooning: Working on the Delta Collegiate, “the first time I had ever been published as a cartoonist.”

On technique and technology: He shuns the Wacom tablets – “I like that feeling of pen to paper,” Fosgitt says – but for color he relies on Photoshop for a smooth, “magazine quality.”

His model for Dead Duck’s sidekick: Goldie Hawn, in her “Laugh In” days. “I love that show,” Fosgitt says, “I drew her with this little chicken beak, basically. It’s that simple.”

Encouraging words on “Dead Duck”: In May 2007 at the annual Motor City Comic Con in Novi, Fosgitt met cartoonist Sergio Aragones (perhaps best known for his “marginals” in Mad), who urged him to find a publisher.

How comic books rotted the minds and morals of postwar American youth: Check out “The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America,” by David Hajdu (in paperback by Picador).

Need even more of a Fosgitt fix? Check out his Dead Duck blog, The Duck Factory. From a recent post: “I got a call from my publishers at Ape a couple days ago, and good news abounds. They’ve packaged up 200 copies of Dead Duck, and they’re currently in transit to my humble digs here in Ann Arbor. And as the top paragraph suggests, I’m pacing around like an anxious daddy to be. Twenty years developing Dead Duck, five years developing Zombie Chick, three years working on the graphic novel, and two years working with Ape Entertainment, and it all boils down to five cardboard boxes filled with my creative brainchildren, to be delivered via Fed Ex stork to my doorstep on Tuesday, Nov. 24th.”

About the writer: Domenica Trevor is a voracious reader who lives in Ann Arbor. Her column typically is published on the last Saturday of the month – but The Chronicle is no slave to publishing schedules, clearly.