In the Archives: Bloomers and Bicycles

Editor’s note: At January’s meeting of the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority board, Ann Arbor’s mayor suggested that the DDA’s transportation committee bring a recommendation to the board to take a position on bicycling on Ann Arbor’s downtown sidewalks.

The fight to keep bikes off of Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti sidewalks dates back to the first appearance over a century ago of what many perceived to be “infernal machines.”

The 1876 Ann Arbor city charter contains no mention of bicycles – it wouldn’t be until two years later that A. A. Pope manufactured the first bicycles in the U.S. The invention spread across the nation, threw city fathers into consternation as they scrambled for their city charters, and incited Ann Arbor’s “Bloomer War.”

It also inspired the creation of a nationwide organization of cyclists, the League of American Wheelmen. Its Michigan chapter’s 1897 edition of their “Road Book” recommended one 271.5-mile jaunt from Detroit to Chicago. Another route circled Lake Erie. The guidebook gave instructions for rides from Ann Arbor to Chelsea, Saline, Whitmore Lake, Pontiac, South Lyon and Dundee.

“Gravel roads will average as shown during entire riding season,” the book stated, “clay ones only in dry seasons.” The L.A.W. received a discount from 66 Michigan hotels ranging from Marquette to Coldwater. In Ann Arbor, the L.A.W.’s hotel was the American House (15% discount), and its Ypsilanti refuge was the Hawkins House (20%).

As the wheelmen helped popularize bicycling, they also warned of restrictions. “Among the principal cities in Michigan the following have bicycle ordinances,” stated the 1897 guidebook, naming 17 cities. “The following cities have no bicycle ordinances: Ann Arbor, Sturgis, and Ypsilanti. In the first two cities, sidewalk riding is not permitted, however.”

Ann Arbor did not yet have a bicycle ordinance, but in 1895, Section 8 of the city’s “Ordinance Relative to the Use of Streets and Public Places” forbade bikes on sidewalks. “No person shall cause or permit any horse, cow, sheep, hog, mule, or other similar animal, or any cart, carriage, dray, hack, cutter, or other vehicle under his or her care or control, to go upon any sidewalk … Nor shall any person make use of any sidewalk … for riding or going from place to place with bicycles or velocipedes.”

Baby carriages and biking children under six years old were permitted.

In November of 1897, the Ann Arbor city council considered and voted down “An Ordinance Relative to Bicycles.” Then in January of 1898, they passed “An Ordinance Relative to Bicycles.” But in March of 1898, they passed “An Ordinance to Repeal an Ordinance Entitled ‘An Ordinance Relative to Bicycles.’”

Ypsilanti was also wrestling with the troublesome vehicle. In 1897, city council passed “An Ordinance to Regulate the Use of Bicycles and Other Vehicles on the Public streets Within the Limits of the City of Ypsilanti.” It included:

Section 1. No bicycle or other vehicle shall be driven at a rate of speed to exceed eight miles per hour upon any street within the limits of the city of Ypsilanti.

Sec. 2. No person or persons shall ride any bicycle or other vehicle on the sidewalk within the limits of the city of Ypsilanti.

Sec. 8. Any person violating any of the provisions of this ordinance on conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not to exceed ten dollars together with the costs of prosecution or imprisonment in the county jail not to exceed twenty days, or both fine and imprisonment in the discretion of the court.

Just one year later, frustrated city fathers raised the ordinance violation fine from $10 ($260 today) to $50 ($1,280), and the possible jail time from 20 to 90 days. Other communities were having trouble, too. Local papers reported that Bay City’s Frank Baker had stolen a bike and was sentenced to three years in the Jackson prison. Compounding the problems, bicycle speeders and sidewalk-riders were difficult to nab. One exasperated resident, F. E. Quigley, wrote to the Ypsilanti Daily Press:

Would it not be a wise thing for this city to purchase a [car] for . . . the police department? For instance, if an officer is wanted in the vicinity of the Normal, a call is put in by phone. Perhaps the police department is closed, the chief being out on street duty . . . The call is of no avail. But suppose the chief is in his office; he attempts to respond by the present method, namely, by walking, and before he can arrive on the scene of action, there is no need of his services, the ‘bird’ having flown . . . Suppose a community is infested with men and boys riding their bicycles on the sidewalks? . . . [I]t seems that we ought to get modern service for the expenditure of money that is being made.

Not three days later, Ypsi police arrested high school student and sidewalk-biker Eugene Minor – the first bicycle crime to appear in Judge Martin Stadtmiller’s court dockets for the previous three years. Minor paid a fine of $3 plus court costs of 45 cents ($76 today). The next day, police arrested another sidewalk-biker, teamster Milton E. Gould, who also paid a fine.

It was a losing battle. Bicycles were by then such an integral part of Ypsi life that the high school and the local underwear factory both had special indoor bicycle storage rooms. Almost all of the underwear factory workers were women who, like men, bought their own bicycles. “Miss Florence Batchelder is the proud possessor of a Crawford bicycle,” noted the April 16, 1896 Ypsilantian.

Some men were less sanguine about women bicyclists and their penchant for wearing bike-friendly bloomers. University of Michigan medical men heard the question discussed at a September 1895 medical convention in Detroit. Dr. I. N. Love came from St. Louis, and spoke on “The Bicycle from a Medical Standpoint.”

“A study of the question of the wheel for women had resulted in an opinion favorable to its moderate use in cases of acute diseases,” Love said. “An hour’s wheeling three times a day is ample.” Love objected to bloomers, “which lessened the respect of mankind for womanhood and blemished the landscape.”

Just a week later in the biweekly journal Medical Century, an editorial addressed bloomers, as well as Love’s presentation:

Their tardy acceptance having been carefully traced to the fact of their hideousness, and now that the shop girls and their kith have accustomed the public eye to the sight … and now that the no better but some finer types of women have taken up and pushed on the shop girls’ initiative into a more graceful expression, the question begins to arise in the minds of the be-trousered populace, “What are they good for and how are they good for it?”

The costume was so beastly ugly that it became by virtue of that token “immodest” … every conscientiously artistic man was forced to put his hands before his face – and look through his fingers – when a bloomer girl went by …

[I]t was only the other day that the Mississippi Valley Medical Convention sat down in Detroit … We read that the doctors in conclave assembled in Detroit were brought to the verge of tears in their reluctant consideration of the ugly old things, and the author of the paper which had for its title “The Bicycle from a Medical Standpoint” grew mournfully sublime as he entered his protest against “such things” and pathetically entreated that the police be instructed to arrest women wearing them. ‘They weren’t pretty,” he sobbed, “and they weren’t nice nohow”.

However, the editorial grudgingly concluded that bloomers were conducive to women’s exercise.

The difficulty of biking in bulky skirts, let alone a corset, led to one UM student’s rebellion, and ultimately, the “Rational Dress Movement,” which advocated less elaborate and constrictive women’s clothing.

The May 1895 edition of the monthly magazine The Bachelor of Arts wrote:

Miss [Edna] Day, a junior, wears bloomers when she rides a bicycle, as all women do who choose. But she can’t ride a bicycle all the time, and finding it an inconvenience to change her raiment from hour to hour she fell into the habit of wearing bloomers around her boardinghouse.

Mrs. Eames, who keeps the boardinghouse, is not a ‘new woman,’ but one of the older fashioned sort, who believes in skirts. She told Miss Day that bloomers did not ‘go’ in her house, so Miss Day compromised and agreed to wear bloomers only when she rode her bicycle. But Miss Brown of the Medical School cried ‘tyranny!’ when she heard of it, and put her bloomers right on and sallied forth into the street, and declared war. Some of the professors’ wives who ride bicycles sided with her, and declared it to be the constitutional right of every woman to wear bloomers with or without bicycles whenever she would.

Then Mrs. Eames rose up and declared that she would have no bloomers worn about her house if she lost every bloomering boarder she had! Now there is war in Ann Arbor.

The Bachelor’s opinion is that only pretty women should wear bloomers at any time.

The bloomer furor eventually resolved itself, and a century later, Ypsilanti uneventfully banned sidewalk biking in a small downtown area. But in larger and busier Ann Arbor, where the sidewalk question currently has proponents on both sides as feisty as Edna Day and company, the city likely has in store a “bloomering” fight.

This biweekly column features a Mystery Artifact contest. You are invited to take a look at the artifact and try to deduce its function.

Last week’s Mystery Artifact contest generated many excellent guesses, ranging from a tatting shuttle to a kite string holder.

The winning guess was from John – a sharpening stone. This is a whetstone, not unlike modern kitchen knife sharpeners, for farm and workshop tools.

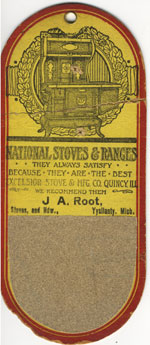

This week’s Mystery Artifact stumped a well-known Ypsilanti historian. It’s about eight inches tall and three and a half inches wide. What might this odd object be?

Take your best guess; answer in the Valentine’s Day column!

“In the Archives” is a biweekly series written for The Ann Arbor Chronicle by Laura Bien. Her work can also be found in the Ypsilanti Citizen, the Ypsilanti Courier, and YpsiNews.com as well as the Ann Arbor Observer. She is the author of “Tales from the Ypsilanti Archives,” to be published this winter. Bien also writes the historical blog “Dusty Diary” and may be contacted at ypsidixit@gmail.com.

Mystery object: a disposable strike plate for lighting matches?

Cosmonican: Interesting guess. As it so happens, I have ol’-timey wooden matches in the kitchen right now, to light the gas stove…but there are two strike plates right on the box. Hmm…

That’s a wonderful story, Laura. It’s funny how the same issues keep coming up, even a century later. (“Dr. I. N. Love” sounds like a sex columnist, if they had such things in the 1890′s).

Thank you, Tom, for such a nice comment!

But your question is better: were there sex columnists in the 1890s? Now I have to know.

You do see euphemistic ads in the old papers offering nostrums and booklets (sent in plain packaging of course) that address various male and female “irregularities,” up to and including emmenagogues, “when health will not permit an increase in family.”

Oops, I meant to say “even better,” pardon.

I don’t know if there were many newspaper writers who devoted themselves to handing out sex advice, but despite the Comstockery of the era there was certainly no shortage of published sex advice available — from cheap reprints of John Cowan’s SCIENCE OF NEW LIFE or by-subscription marriage manuals like DR. CLARK’S NEW ILLUSTRATED MARRIAGE GUIDE (the Union Purchasing Agency republished this through the 1880s and 1890s) or even Dr. Alice B. Stockham’s KAREZZA: ETHICS OF MARRIAGE (1896) which noted “By tenderness and endearment, the husband develops a response in the wife through her love nature, which thrills every fiber into action and is a radiating tonic to every nerve.”

Even earlier of course you had the various Jordans and their museums of “Anatomy, Science and Art” (“For Gentlemen Only”) in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and San Francisco or even way before that the pseudo-Aristotle and his “Masterpiece” which counseled “Neither should these amorous engagements be too often reiterated, till the conception be confirmed; and even then the bridegroom should remember, that it is a market that last all the year and so should have a care of spending all his stock too lavishly. Nor would a bride like him at all the worse for it, for women rather chuse to have a thing well done, than have it often, and well and often too can never hold out” (New-England, “For the Publishers,” 1821).

One can only assume that such tender sentiments were not foreign to the men and women of Washtenaw County, where many a fancy was no doubt was fired by the sight of Bloomers in the Spring time.

And heck — straying a bit from adult fare, one shouldn’t forget Mary Wood-Allen, M.D. (1841-1908) who published several books sex education for children and their parents (THE MARVELS OF OUR BODILY DWELLING [1895], ALMOST A MAN [1895 et seq.], etc.) under her own Wood-Allen imprint in Ann Arbor.

That’s quite interesting, Garrett, not to mention an interesting local connection; thank you, I’ll check those out.

Cosmonicon, I think you’re right on the money, except for the disposable part. I imagine the hole at the top is to hang the strikeplate on or next to your stove – the equivalent of the modern-day magnetic business card.

Thanks Pete, but I’ll stick with disposable. It looks flimsy, and it’s bound to get gunked-up with kitchen grease and match residue, plus the abrasive is bound to wear off. Laura, I wouldn’t strike a 19th century match on the box, unless I wanted to lose a hand.

Garrett: Do you think that such works as those you mention might be discreetly advertised perhaps in the back of something as then-popular as Lady Godey’s Book? I tried to find a copy to see online but could not.

Based on my own reading of old papers and your informative comment I’m starting to see a pattern. Today: Lots of such advice, appears explicitly as part of magazines and newspapers (Dan Savage’s column, marriage quiz in Cosmo, &c.) Then: Lots of such advice, does not appear explicitly as part of magazines and newspapers *but* material is readily available via e.g. euphemistic 19th-century ads in Ypsi papers. Perhaps I’m wrong. It’s quite fascinating to learn more about the cultural context of that time.

Pete and Cosmonican: It may be irrelevant, but this item is almost ripped in half and is kept in a protective envelope to keep it from ripping apart.

Cosmonican: Oh, sorry, by “ol’-timey” I only meant a modern wooden match. I kinda get a kick out of ‘em (simple pleasures).

No fossy jaw for me, nosir! (shudders)

Laura,

Could it be an advertising calendar from the J. A. Root Company who most likely sold and or distributed these stoves? Of course I assume the calendar pages are torn off. By the way, was that a proper way to spell Ypsilanti (with a Y at the end in those days)?

Dave: That is another good guess. No, “Ypsilanti” was never spelled with a terminal “y”.

You can see they spelled it “Yysilanty” or “Yysllanty.”

Likely reason: I note that the printing of the “National Stoves and Ranges” boilerplate info looks different from the local-distributor “J. A. Root” printed info. Guessing they printed up a run of blank items somewhere near Quincy, Ill. (where the word “Ypsilanti” would presumably be unfamiliar), and then customized them with the various dealers’ names before sending them out.

In 1916 Root was 1 of 2 stove and range dealers in Ypsi. Root is listed as at 48 E. Cross (now the Hair Station in Depot Town near Cafe Luwak). The other stove dealer was L. K. Foerster over at 115 W. Michigan Ave. Foerster is listed as having a telephone # (66) and Root is not, so I’m hazarding a guess that Root’s was the smaller operation.

Laura,

I might venture a second couple of possibilities to the mystery item as, one, a salesman trade advertising card or an advertising fan of the era.

Dave, those are two more interesting possibilities, especially given the huge range of forms in which advertising ephemera were made.

Mary Wood-Allen of Ann Arbor, a pioneering sex educator, was the National Superintendent of Purity of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), and editor of a magazine called “American Motherhood”. In the 1890s, she lived in a comfortable house on the north side of Washtenaw Avenue, which unfortunately had to be removed when Observatory Street was extended to Washtenaw, about 45 years ago.

Wystan: The National Superintendent of Purity?

Thank you for your informative and interesting comment; I did not know that.

It looks as though from your description that her house was just about here: [link]

Readers may also find interesting the reference

to the Michigan L.A.W. guidebook:

“It also inspired the creation of a nationwide organization of cyclists, the League of American Wheelmen. Its Michigan chapter s 1897 edition of their Road Book recommended one 271.5-mile jaunt from Detroit to Chicago. Another route circled Lake Erie. The guidebook gave instructions for rides from Ann Arbor to Chelsea, Saline, Whitmore Lake, Pontiac, South Lyon and Dundee.”

Here’s the book online, turned to a page of Ann Arbor local routes. It makes fascinating reading. [link]

And we think our roads are bad. And yet there were cyclists back in 1897 who were riding 10-20,000 miles a year: [link]

All while being better dressed.

Philip: That is a great link; thank you!

You are spot-on…those hardy L.A.W. folks battled down gravel, mud, washboard roads…spiffily.

I personally am a lackadaisical winter biker but am nowhere near the mileage, style, or panache of the erstwhile L.A.W. members.

Two L’s; Phillip; excuse me. Long day.

It was a brilliant idea, Laura, to write about bicycle ordinance history right now.

I wish there had been a picture of these bloomer things, for those of us who don’t remember ‘em.

Christopher: Thank you for your nice comment. Much as I would like to take credit for this topic, it was my excellent editor’s idea to cover this subject.

Just for fun, I have posted a number of bloomer pictures (including one cartoon) for you to examine right over here: [Link]

I hope you enjoy them!

To Laura Bien: Search Google for Godey’s Lady’s Book rather than Lady Godey’s Book and you’ll find what you’re looking for, I believe. I remember some framed illustrations from Godey’s (a fashion magazine, perhaps) on the bedroom wall of a friend’s mother.

Oh, I can never remember that name correctly, thank you. :)

Local newspaper publisher Junius Beal was a prime mover in The Ann Arbor Bicycle Club, high wheel daredevils of the latter 19th century. There is a photograph of the Wheelmen posing in front of the old County Courthouse in many of the historic books about Ann Arbor. In an 1880s photograph in front of Beal’s home, that is now the site of the downtown library, Beal is shown balancing on a big wheeler. Beal was such an enthusiast that he spent his honeymoon riding his tandem bicycle–which is now the property of the Washtenaw County Historical Society and was recently on display when weddings was the theme. I believe he and his wife spent their honeymoon in Bermuda.