In the Archives: Criminal Girls

In the fall of 1883, delegates from almost every state attended the National Conference of Charities and Corrections in Louisville, Kentucky. Penologists, prison officials, and representatives from state institutions for the blind, deaf, orphaned, insane and “feeble-minded” gathered at Louisville’s Polytechnic Institute for eight days of presentations and discussions.

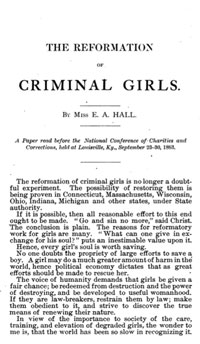

Emma Hall’s 1883 talk, delivered at the National Conference of Charities and Corrections in Louisville, Kentucky, analyzed the best methods of reforming girls.

On the morning of Sept. 26, Ypsilanti resident and Normal School graduate Emma Hall faced a distinguished audience. “The reformation of criminal girls,” she began, “is no longer a doubtful experiment.”

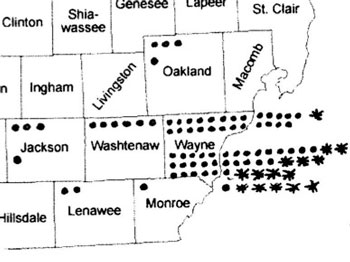

Born February 28, 1837 on a farm in Lenawee County’s Raisin Township, Emma was the second of her parents Reuben and Abby’s eight children. Most of the family relocated to Ypsilanti around 1870. Reuben’s teaching background and Abby’s upbringing as a Congregational minister’s daughter may have influenced Emma’s career as a prison reformer. She became Michigan’s first woman to lead a state penal institution, and was later made a member of the nation’s top prison advisory committee.

After graduating from the Normal in 1861, Emma taught recitation at Professor Sill’s Seminary for Young Ladies in Detroit, for a yearly salary of $550 [about $10,000 in 2014 dollars]. Emma met Detroit House of Corrections prison superintendent Zebulon Brockway. Beginning with his work at the Detroit prison, which opened in 1861, Brockway would become a nationally-recognized though controversial prison reformer.

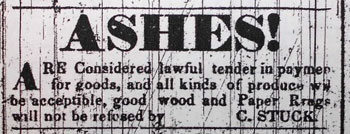

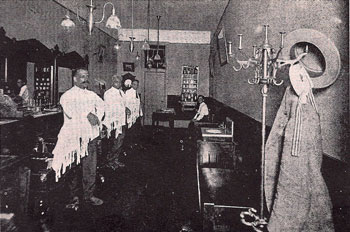

In 1868, Brockway opened the House of Shelter. This adjunct to the Detroit House of Corrections offered a radical experiment for women prisoners, many of whom had been arrested for prostitution. Instead of barred cells, the House of Shelter offered a comfortable group home in which each woman had her own bedroom. The home was furnished and decorated as a well-to-do middle-class home.

Brockway made Emma its first matron. She moved in and lived full-time with the women. [Full Story]