Council Banks on Single-Stream Recycling

Ann Arbor City Council meeting (March 15, 2010) Part 2: Part 1 of the meeting report handles the range of various topics at the meeting that did not fall into the general category of recycling. Part 2 focuses specifically on the two recycling-related resolutions approved by the council.

Tom McMurtrie, left, is the city's solid waste coordinator. Jim Frey, right, is CEO of Resource Recycling Systems, a consultant for the city on recycling.

The two separate resolutions correspond to the two facets of the new recycling system for Ann Arbor, which will be deployed in July 2010.

One resolution revised the contract with Recycle Ann Arbor (RAA) for curbside recycling pickup to reflect the single-stream character of the system. Residents will no longer place paper and containers in separate 11-gallon stackable totes to be hand-emptied by RAA drivers. Instead, residents will put all their recyclable materials into a single rollable cart with a lid. Drivers will operate a robot arm from inside the truck to lift and tip the single cart’s recyclable contents into the truck.

The other resolution approved by the council authorized a contract with RecycleBank to implement an incentive program for residents, based on their participation in the recycling program and the average amount of materials recycled on their route.

Both the conversion to the new system and its associated incentive program came under criticism during public commentary. During council deliberations it was the incentive program that was given the most scrutiny by councilmembers – with Stephen Kunselman (Ward 3) voting against it. The contract with RAA was given unanimous support from the nine councilmembers who were present.

The arrangements with RAA for collection and with RecycleBank for the incentive program are separate contracts with separate entities – the single-stream system could be implemented without the incentive system. But it became apparent during council deliberations that the idea that the city council might opt for a single-stream system without the incentive program was not something city staff had planned for: The single-stream carts are already molded with labels “Earn rewards for recycling.” [Clarification: The authorization for the in-molded cart labels had not been made before the council approved the incentive contract.]

Background on City Council History with Single-Stream

Monday was not the first time the city council had contemplated the single-stream issue. The council heard a presentation at its Oct. 12, 2009 work session on the approach, including the incentive program for residents to set out their new single-stream carts for collection.

There was some initial confusion in the community about how the carts equipped with RFI (radio-frequency identification) tags would factor into the incentive program. Trucks will not weigh each individual cart as its contents are collected. The RFI scan simply measures participation of a household on any given day, and that participation is then assigned the average weight of all participating carts when the truck is weighed at the materials recovery facility (MRF).

At its Nov. 5, 2009 meeting, the council authorized upgrades necessary for the materials recovery facility (MRF) – some additional processing will be required to separate the materials, given that items will arrive mixed together. And at its Dec. 21, 2009 meeting, the council authorized the purchase of four new trucks, plus 33,000 carts equipped with RFI chips.

The authorized total of capital investments – around $6 million – was made with reserves from the solid waste fund, which receives revenues from a dedicated millage. The increased volume of recycling expected from the single-stream system is expected to benefit the city’s balance sheet in two ways.

First, every ton that can be recycled instead of landfilled will save roughly $25 in tipping fees at Woodland Meadows in Wayne, Mich., where the city buries its trash. Second, the more recycled material that the city can collect, the more material it can sell on the recycled materials market. The estimated payback period for the investment is contingent on how the market for recycled materials plays out. The city is projecting that if the market stays in the mid-range for performance, the payback period for the investment will be about six years.

Who’s Who in Ann Arbor Recycling

At the podium at different times during the city council meeting were a range of people representing various organizations. Tom McMurtrie is the city’s solid waste coordinator. He was joined much of the time at the podium by Jim Frey, CEO of Resource Recycling Systems, a consulting firm.

John Getzloff is the representative of RecycleBank, which will have the contract to administer the incentive program. RecycleBank’s parent company is called RecycleRewards, and reference by speakers at the meeting varied between these two entities.

Melinda Uerling is the executive director of Recycle Ann Arbor – its current contract for dual-stream collection was amended Monday night to accommodate single-stream recycling collection. Recycle Ann Arbor is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Ecology Center, an Ann Arbor nonprofit.

Single-Stream Public Commentary

Kathy Boris spoke against the adoption of a single-stream curbside recycling system. She said that the true business of the city government is to provide services, which included collection of recycled materials, and that the current system is providing good service. She contended that the current two-stream system is working, and that she was not aware that it was deficient. The cost savings associated with a single-stream system, she said, were offset by the need to purchase new cards, trucks, and add staff at the materials recovery facility. The current economic down time, she said, was the wrong time to undertake this system.

She cautioned the council that the point of recycling is not to achieve great volume, it’s to be able to sell what you have collected so it can be manufactured into products that people will buy. She warned that even with additional processing of the material that is mixed through the single-stream approach, you will still get contamination. She questioned whether it was in the best interest of the city to sacrifice quality in the interest of increased volume – it jeopardized the city’s ability to close the recycling loop by selling the material.

Rita Mitchell began her remarks on the single-stream recycling system by saying that she had found some money for the budget – she asked the council to vote no on the two resolutions before them concerning single-stream recycling [One resolution authorized a contract with Recycle Ann Arbor to perform the curbside collection, while the other authorized a contract with RecycleBank, the vendor that will be implementing the incentive program.]

Mitchell told the council that they would save up to $6 million by voting no. She suggested using the funds instead for police services and park maintenance. Mitchell acknowledged that adding additional types of plastics to the set of materials that are accepted is a good idea, but not one that is worth the $6 million investment. She also asked what would happen to the batteries and the oil, which are currently picked up curbside. With the $3-per-car entry fee now imposed at the city’s drop-off station, she warned that batteries and oil would wind up going to the landfill.

Mitchell cautioned that the incentives offered through RecycleBank could lead to increased consumption of unnecessary things, which was counter to the goals of recycling. She also objected to the roughly $200,000 annual cost to administer the program. She characterized the incentive program as a marketing project for tracking consumer behavior. Comparing RecycleBank’s slogan of “recycle, redeem, reward” to the one that’s more familiar to recyclers, she asked, “What happened to ‘reduce, reuse, recycle?’” She cautioned the council that they needed to look at the entire waste stream picture and that the goal needed to be a reduction both in solid waste and recycling.

Responding to the idea that the time has come for single-stream recycling, Glenn Thompson allowed that it had come … and gone. After careful study, he said, Berkeley, Calif. decided to retain its two-stream system. The University of Colorado had also recently concluded that the negatives associated with a single-stream system outweigh the benefits and had made a decision to stick with the two-stream system.

Those decisions, he said, were made this year, based on the quality of the resulting materials. Thompson reminded councilmembers that Ann Arbor has a 90% participation rate in curbside recycling for its two-stream system and has a 50% diversion rate. At the same time that the council was planning to spend $6 million on a speculative program, it was considering canceling loose-leaf collection, eliminating holiday tree collection, and had already imposed a $3 fee to enter the drop-off station. Thompson, like Mitchell, characterized the RecycleBank incentive program as a “marketing campaign.” Thompson called on the council to make this the watershed issue, the one where the council says no to an unnecessary “pet project.” He asked the council not to spend $6 million to benefit consultants and contractors.

[Later, during council deliberations, Sandi Smith (Ward 1) would question the connection that was made by some speakers during public commentary between the elimination of the loose-leaf collection and holiday tree pickup on the one hand, and the implementation of single-stream recycling on the other.]

Lou Glorie made her remarks during public commentary reserved time in the form of a skit in which she played both roles. It was a household conversation about recycling after conversion to a single-stream system. She included a mixing bowl as a prop, into which she dumped various materials. She then mixed them together, symbolic of what would happen to materials in a single-stream system.

RecycleBank’s Incentive Contract

Councilmembers had several areas of concern – from the 10-year length of the contract, to the need to have an incentive program at all. From the staff memo providing the rationale for the incentive program:

Based on data collected from comparable communities around the country, it is estimated that the single-stream program without RecycleBank would increase recycling rates about 28%, from 357 pounds per household per year to 457 pounds. This increase will be due to both the convenience and higher capacity of the new single-stream cart, as well as the additional materials that will be collected in the program. For example, all plastic bottles and tubs (except #3 and styrofoam) will be accepted under the new program.

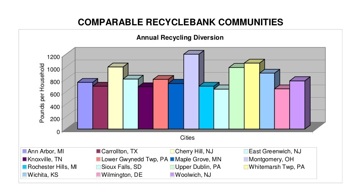

With the RecycleBank incentive program, it is estimated that those same recycling rates will increase from 357 pounds to 752 pounds, or over 200%. The attached chart compares that 752 pound figure with other similar communities that are currently enrolled in the RecycleBank program.

Even at 752 pounds per household per year– a 200% increase in volume compared to current levels – Ann Arbor would be a fairly middle-of-the-pack RecycleBank client.

Here's how Ann Arbor's recycling performance is projected to stack up against other communities after implementation of the RecycleBank program. Ann Arbor's is the leftmost column. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

A chart supplied by RecycleBank shows five other cities that collect more than 800 pounds per household per year.

Marcia Higgins (Ward 4) led off council deliberations with a question about the length of the contract for RecycleBank: Why was it a 10-year contract for something that’s a new program?

Tom McMurtrie, the city’s solid waste coordinator, explained that it was based on the significant investment in technology and capital equipment required to install the RFID recognition equipment. Higgins also pointed out that the contract was for $200,000 per year over the course of the 10-year contract. She asked, “Why do we feel like we need to have this?” She put her question in the context of the already high rates of participation and recycling by Ann Arbor residents.

McMurtrie allowed that Ann Arbor residents did in fact have a high rate of participation. But he pointed out that communities like Rochester Hills and Westland, which had implemented single-stream cycling together with the incentive program associated with RecycleBank, now surpassed Ann Arbor residents – measured in terms of pounds of recycled material per household.

Jim Frey said that the length of the contract was related partly to the interest in cultivating the long-term loyalty of merchants who participated in the incentive program through coupon offerings. The idea was to use the incentive rewards to lower the cost of living for residents. The idea was also to have a longer-term relationship between residents and merchants.

In terms of Ann Arbor residents’ recycling performance, said Frey, they are no longer in the top 25% – “really not that great, to be honest with you.” The idea was to bring the performance, measured in terms of pounds per household, back into the top 90th percentile. He concluded by saying that Ann Arbor did have good participation rates, but that the performance was not as good as communities that had implemented incentives with RecycleBank.

Higgins asked if those other communities that had implemented RecycleBank, like Rochester Hills and Westland, had also converted to single-stream recycling. Frey confirmed that those two communities had implemented single-stream along with RecycleBank.

Higgins wanted to know if Ann Arbor’s recycling performance could be expected to bump up some anyway, just due to the implementation of the single-stream system, independently of any incentive program. She wanted to know what Rochester Hills’ and Westland’s performance in its two-stream system looked like before implementing the single-stream system, plus the RecycleBank incentive system.

Rochester Hills’ numbers for the two-stream curbside system were around a 30% participation rate, with around 150-200 pounds per household, Frey said. Now their participation rate was around 80%, with around 650 pounds per household. Westland, which previously had no curbside recycling, is now showing recycling levels of 800 pounds per household – roughly double the amount recycled in Ann Arbor, he said.

Higgins responded to an example from Frey of a community going from 30% to 80% participation through RecycleBank by pointing out Ann Arbor’s 80-90% participation rate with the two-stream system. Tom McMurtrie countered that it’s not just about participation but rather the amount of materials. Higgins asked when the 80-90% participation rate had last been measured for Ann Arbor in a two-stream curbside recycling program. McMurtrie told her it had been several years ago.

Carsten Hohnke (Ward 5) focused on the idea that there will be an increase in recycling performance simply due to the conversion to a single-stream system, but there will be an additional increase from the RecycleBank incentive rewards system. McMurtrie confirmed that the conversion to single-stream itself – which included more kinds of materials (plastics), and increased volume of the curbside container – would result in some gains. But the incentive program, said McMurtrie, which really “gives it that shot in the arm.”

Noting that Ann Arbor was not the first to lead the way by implementing an incentive program like RecycleBank, Hohnke asked what that boost actually looked like. John Getzloff of RecycleBank reviewed the Westland and Rochester Hills program and added the example of Cherry Hill, N.J., which had increased its recycling levels from 600 pounds per year to 900 pounds per year. Getzloff told the council that RecycleBank operated in 20 states across the country, including large cities like Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Chicago.

Frey suggested that in analyzing Ann Arbor’s situation, they estimated that 500 pounds of recycling per household could be attributed perhaps to just having a bigger container. There were many communities that had implemented single-stream recycling with carts only, and generally they achieved between 450 and 550 pounds of recycled materials per household. Hohnke then concluded from that discussion that the city could be confident there would be some additional boost from having the RecycleBank incentive program.

But he noted that the incentive program came with a cost – $200,000 per year. Against that cost had to be weighed the savings in tipping fees for the landfill. Asked Hohnke, “If you do the math, how do they compare?” Frey indicated that for every additional ton of material that was recycled, a savings of $25 would be realized. Through the sale of the material, there would be a benefit, as well. They projected that over the next five years, the incentive program would cover its costs.

In addition to that, Frey said, the value of the incentive rewards to each household would average around $250 worth of rewards a year. With 28,000 carts, that reflected a $7 million benefit to the community, he said. Hohnke concluded from this that implementing the incentive program over the course of five years would save the city money.

Higgins wanted to know what the ratio of renters to homeowners was in the communities that had been used for comparison, noting that there were 45% renters in Ann Arbor. Getzloff explained that the benefit of the rewards program came to the resident, not necessarily the property owner. If people moved within the city of Ann Arbor, they would take their accounts with them.

Higgins also came back to the fact that it was a very long contract. What if, two years into the contract, it is not working for the city, she wondered? McMurtrie replied that RecycleBank had been around since 2004 and therefore they had a history. Higgins came back with the point that it was not as long a history as the contract the council was being asked to sign. McMurtrie noted that the city had the ability by the terms of the contract not to fund the program.

Sandi Smith (Ward 1) noted that on the chart that had been provided to councilmembers, curbside recycling levels increased dramatically but flattened out rather quickly over the five-year period that was estimated. Frey accounted for that by saying that there was a built-in conservatism in the estimates.

Smith asked about the possibility that utilization rates did not improve over time. Getzloff indicated in that case, they would do additional outreach in the community. Frey pointed out that it could be a very targeted outreach because they would know exactly which households were not participating in the program. Smith elicited from Getzloff that the merchant partners for the incentive program would be a combination of national and local partners and that there would be a $540 cap on benefits to any one particular household. The cap is a way to prevent people from trying to cheat the system – by loading their carts with materials other than recyclables.

Mayor John Hieftje said he was intrigued by the incentive program and wondered if it would be possible for the community to use the coupons to support local nonprofits like Food Gatherers. Getzloff indicated that RecycleBank’s main focus was on their Green Schools program and other national charities. Support for local charities was not in the contract that the council was considering. Hieftje characterized the incentive program as a good investment.

Stephen Kunselman (Ward 3) asked who collected the data on recycling tonnage. McMurtrie clarified that it’s collected by trucks and is then uploaded to RecycleBank’s system.

Kunselman reflected on the fact that the roughly $200,000 per year over the life of the 10-year contract represented $2 million. He established that the escape clause for not funding the program was slightly less than $200,000 a year – to cover the under-appreciated capital investment in the trucks. In light of that, Kunselman wondered why it was necessary to have a 10-year contract. Getzloff indicated that there were a variety of term lengths for RecycleBank contracts and that the best price came with the longest one – a 10-year contract.

Kunselman returned to the topic of Ann Arbor’s already high 80-90% participation rate. Based on the chart that had been handed out to councilmembers, Kunselman wanted to know how much of the doubling of recycled tonnage could be attributed just to the implementation of the single-stream system independently of the incentive program.

Frey went through a chart that showed how estimates of the current level of 5,084 tons – for single households in Ann Arbor – would rise to 10,708 tons in the second year of the program. Of those 5,624 extra tons, fully 4,201 were attributable to the incentive program.

Kunselman also questioned whether the city would in effect be paying twice for the educational efforts of both Recycle Ann Arbor and of RecycleBank. McMurtrie replied by saying that “We’re all in this together.” RecycleBank, McMurtrie indicated, is simply a new layer.

Kunselman then asked whether there were examples of RecycleBank in other college towns. Kunselman said that he was not sold on the idea that the city needed incentives as opposed to more education. Getzloff said that the incentive program educated people by keeping the idea of recycling foremost in their minds. Kunselman responded by saying that he had a difficult time believing that with a 80-90% participation rate by people who were conscientious about recycling, that a dramatic gain like Getzloff was describing could be possible.

Frey indicated that he’d been in the business of recycling almost 30 years and that communities spend millions of dollars in education, and that it’s different for each person and different for each household. What’s different about the incentive program, he said, is the common interest that it defines. He stressed that it works, and it’s amazingly effective.

Frey indicated that there were University of Michigan students who were really interested in doing a pre-test and post-test of the system. So Kunselman asked if it was possible to delay implementation of the incentive system for one or two years to see how well the conversion to single-stream worked with just the educational efforts of Recycle Ann Arbor.

McMurtrie responded by saying that the city council had already approved a purchase order for 33,000 carts and that the carts have in-molded labels saying that there would be rewards. Kunselman expressed his objection to the idea that they were putting advertising for RecycleBank on the carts. McMurtrie indicated that it was not advertising, but rather the phrase: “Earn rewards for recycling.”

Christopher Taylor (Ward 3) clarified that the escape clause in the contract was designed to cover an investment that had not yet depreciated. He wanted to know how much that investment was. It boiled down to $20,000 per truck, plus installation of equipment at the materials recovery facility (MRF) – a computer that would download data to Recycle Ann Arbor. The cost of recruiting incentive rewards merchant partners, sending a team to educate people and funding the Green Schools program is just the cost of doing business, confirmed Getzloff.

Taylor then segued into a discussion of what exactly RecycleBank’s business model is. He wondered how they could offer $7 million in benefits based on a $200,000 per year payment from the city. Getzloff clarified that the $7 million reflected a co-spend, and that it was essentially costless to them. The parts of the incentive program that cost RecycleBank money are gift cards, movie tickets and the Green Schools program, Getzloff said. Taylor concluded from Getzloff’s remarks that the primary benefit to RecycleBank is from having the contract with the city. The heart of RecycleBank’s business model was the customer satisfaction of the city of Ann Arbor, Taylor said: “We are your customer.”

Marcia Higgins (Ward 4) offered an amendment that stipulated that in three years after implementing the program, the city administrator would report back to the council on its effectiveness. Higgins’ amendment was unanimously approved.

Mayor John Hieftje asked McMurtrie if there was any reason to believe that the incentive program would cause people to buy more stuff. McMurtrie said he could not see that happening. He noted that there is a cap on how much you can earn from the rewards program. He stressed that the city’s first message was to reduce.

Outcome: The contract with RecycleBank for an incentive program for recycling in connection with the city’s new single-stream program was approved, with dissent from Stephen Kunselman.

Recycle Ann Arbor Contract

Also before the council was a contract revision with Recycle Ann Arbor, which currently collects recyclables curbside in a two-stream system. The key revisions to the contract are as follows:

The contract currently pays $19.30 to $102.58 per ton (depending on the annual tons), as well as $2.41 per service unit, with a total of 48,886 service units.

The proposed amendment modifies the provisions for compensation to RAA and extends the contract for an five additional years. The amendment will pay a revised rate of $18.74 to $30.00 per ton, as well as $3.25 per cart, which will replace the per service unit fee. The number of carts in the city will be lower than the number of service units because most multi-family service units will share carts. It is estimated that the new program will start with 32,800 recycle carts.

Carsten Hohnke (Ward 5) led off the counci’s deliberations by reading a statement of support for the resolution from Margie Teall (Ward 4), who could not attend the council meeting.

Sandi Smith (Ward 1) raised the issue of the connection that some of the public speakers had drawn between the implementation of a single-stream system and the possible elimination of the city’s loose-leaf collection program and its holiday tree drop-off. She asked for confirmation of her understanding that the leaf collection program was simply inefficient.

Tom McMurtrie, the city’s solid waste coordinator, confirmed Smith’s understanding of the loose-leaf collection system. Sue McCormick, public services area administrator, said the loose-leaf collection system was something the city had talked about for a number of years – it generated a very large number of complaints, due to the fact that there were challenges inherent in timing the collection to coincide with the dropping of leaves from trees in any given season.

The unpredictable first snowfall was also a factor, said McCormick. Raking leaves into the street for pickup – a key feature of the loose-leaf collection program – in areas where there was on-street parking was particularly problematic, McCormick said. [At the council's budget retreat in December 2009, McCormick had said about the loose-leaf collection program: "We cannot do it well."]

A second reason for eliminating the loose-leaf collection program, said McCormick, was to contain costs – the city expected around a $450,000 reduction from the solid waste millage revenues in the coming year. It would be somewhat cheaper – by about $100,000 per year – to move to a containerized system for leaf pickup. Smith drew out the fact that the city would continue to pick up leaves, but simply require that they be placed in paper bags or in one of the city’s compost carts. McCormick said that some residents had found it useful to place leaves in the compost carts over several weeks, instead of the all-at-once approach inherent in the loose-leaf collection program.

The rationale for the single-stream system, said McCormick, was to provide a higher degree of service with a payback period of around six years for the capital investment. Each of the programs – loose-leaf collection and single-stream – stood on their own, she said.

Stephen Kunselman (Ward 3) said the initial approvals for the switch to single-stream recycling [authorization for the MRF upgrade, for example] had come in November 2009, before he served on the city council, so he wanted to get a clearer understanding of the general issue.

How do we have employees of a private vendor driving a city truck with a mechanical arm to pick up recycling, and also city workers driving city trucks with mechanical arms to pick up solid waste, Kunselman asked. He said he was a former driver for RAA and just wanted to get a clearer understanding. Kunselman also wanted to know: When did the contract actually end, given the five-year extension?

Tom McMurtrie, the city’s solid waste coordinator, said that until 1991, when he first began working for the city, the contract with RAA was sole-sourced. In 1991, the two-stream system was implemented – McMurtrie said he went out to bid for that system. In the time from 1991 to 2003, that contract was bid out three times. In 2003 they converted to the current performance-based contract, which ends in 2013. The extension for five years would put the end date in 2018.

The compensation for RAA drivers compared to city workers, McMurtrie said – once the better benefits for city workers were factored in – worked out roughly as follows: $19-20/hour for RAA drivers; $35/hour for city workers. McMurtrie said that the city was looking at the idea of privatizing the solid waste collection system as well. Melinda Uerling, executive director of RAA, confirmed McMurtrie’s information on lesser benefits associated with RRA driver compensation – there are health benefits, but no retirement system.

Melinda Uerling, executive director of Recycle Ann Arbor, and Tom McMurtrie, the city's solid waste coordinator.

Hohnke addressed the concern about the possibility that RecycleBank incentives would cause greater consumption, so he drew out the fact that RAA’s message continued to be to reduce, reuse, and recycle, with recycling one of a three-part strategy. Uerling confirmed that this was part of RAA’s message. They focused their message on recycling, she said, whereas RecycleBank would be focused on their rewards system.

Hohnke said there were financial, environmental, and quality-of-life benefits to the single-stream system and he would be supporting the move.

Prompted by Hieftje to explain the change in compensation in the RAA contract, McMurtie said that there was previously a rapid step-up in the per-ton compensation after 10,000 tons, with the idea that RAA would need to add staffing after that tonnage level. With the new single -stream system, he said, they will have already achieved those efficiencies, and it would not be necessary to ratchet up the compensation rate at such a fast rate.

Hieftje also elicited from Frey the fact that the market for recyclables was starting to recover and that Ann Arbor was able to move all of its collected material on the market.

As an example, Frey said, cardboard was in the low 100s [dollars per ton] before the market crashed, and now it was in the 150s.

Hieftje also elicited from McMurtrie and Frey the fact that batteries would no longer be collected curbside under the single-stream system. This is a function of the fact that drivers will no longer be climbing outside of the trucks to pick up batteries and oil.

Hieftje said that one of the advantages of the carts for recycling, as opposed to the two-stream totes, would be an improvement in the “clean look” of the city. He said that in his neighborhood, residents had started setting out their two-stream totes for collection that evening, and there was already cardboard that was starting to blow around.

Mike Anglin (Ward 5) asked about the fact that around 35% of the materials that go through the MRF come from the city of Ann Arbor. The other 65% come from other communities. Frey indicated that in the future the city’s tons would amount to a greater percentage and that the merchant tons would need to find another facility. The MRF would continue to be a regional facility, Frey said, but the relative proportion of the city’s material would increase.

Kunselman asked if monthly data on the materials collected could be provided so that the city could “see how we’re doing.” McMurtrie indicated that more frequent reports on the data was an issue he’d been thinking about – currently the figures are reported annually as part of the city’s State of Our Environment Report.

At the conclusion of the deliberations, Kunselman and Hieftje engaged in a bit of recycling one-upmanship. Kunselman had previously cited his experience as an RAA driver. Hieftje cited his service on the RAA board. Hieftje then quoted an unnamed person who had helped to start RAA – to the effect that recycling needs to be as easy as putting out the trash. Kunselman noted that the unnamed person was his ecology student teacher at Pioneer High School – he’d been inspired by him at a very young age.

Outcome: The contract revision with Recycle Ann Arbor for curbside recycling was approved unanimously.

A Question To Be Recycled

Publication of this part of the meeting report was delayed while The Chronicle sought the answer to a question related to the incentive program – which is still not answered, but we plan to cycle back to it at a future date.

The question relates to how well Ann Arbor residents stack up against other communities that have a RecycleBank incentive program. While the 90% participation in Ann Arbor’s curbside program is high, Ann Arbor’s per-household figure of 357 pounds per year doesn’t stack up favorably with the more than 600 pounds that Rochester Hills residents are achieving.

What was not part of the council deliberations, or in the information that city staff provided to them, however, was the pounds-per-household data for material that goes into the landfill.

When comparing Rochester Hills to Ann Arbor, the 600 pounds versus 357 pounds is part of the story. The other part of the story is the X pounds per household that Rochester Hills throws into the landfill, versus the Y pounds per household that Ann Arbor throws in the landfill.

Our question, currently being handled by city staff, is this: What are X and Y?

To see that getting the answer to the question is not just a matter of diversion rates, consider two communities, City A and City B. City A recycles 500 pounds per household and throws 1,000 pounds into the landfill. City B recycles 750 pounds per household and throws out 1,250 pounds into the landfill. City B outperforms City A in terms of its pounds recycled per household (750 is more than 500) and also outperforms City A in term of diversion rate (37.5% is better than 33%).

Yet there is some sense in which City B is doing a “better job” with resource management – there’s only 1,500 pounds of material carted away from the curb in City A, versus 2,000 pounds in City B.

From Rochester Hills we obtained the roughly one year’s worth of data since April 2009, when the city implemented its RecycleBank program: 6,054 tons of recycling, 16,261 tons of landfilled trash, and 6,397 tons of compost. Those amounts are collected from 19,350 households.

In the most recent article for The Chronicle written by Matt Naud, the city’s environmental coordinator, on the city’s environmental indicators, the breakdown for Ann Arbor’s residential waste only was 28% recycled, 46% landfilled and 26% composted.

Based purely on that breakdown, it looks like Ann Arbor’s performance on diversion rates might be better than Rochester Hills, even though its pounds-per-household recycling numbers are not as good. What we’re still checking is whether the Rochester Hills data we have and the numbers from Naud’s article really reflect an “apples-to-apples” comparison. To the extent that Rochester Hills data might include commercial waste, along with the residential, its diversion rate would be skewed lower.

Present: Stephen Rapundalo, Mike Anglin, Sandi Smith, Tony Derezinski, Stephen Kunselman, Marcia Higgins, John Hieftje, Christopher Taylor, Carsten Hohnke.

Absent: Margie Teall, Sabra Briere.

Mayor John Hieftje announced that councilmember Sabra Briere (Ward 1) and Margie Teall (Ward 4) were absent due to the flu. Later Carsten Hohnke (Ward 5) had to leave the meeting somewhat early to tend to a sick family.

Next council meeting: April 5, 2010 at 7 p.m. in council chambers, 2nd floor of the Guy C. Larcom, Jr. Municipal Building, 100 N. Fifth Ave. [confirm date]

I’m having trouble reconciling these two statements in the article:

“Trucks will not weigh each individual cart as its contents are collected.”

“…Frey pointed out that it could be a very targeted outreach because they would know exactly which households were not participating in the program.”

Re:[1]

The first statement is followed in the article by the explanation that I think reconciles the two:

The RFI tag on the cart allows the truck to measure participation — as defined by setting out your cart. The weight of that cart’s contents isn’t measured by the mechanical arm, however. The weight of the truck is measured at the MRF and that weight is distributed as an average across participating households. The participation in the program (as defined by setting your cart out) won’t be a perfect correlation to “green behavior” but it will provide a way to be more efficient with a mailing to households, for example. Why mail to households that set out their cart every week?

If they are not weighing the container, It would appear that they are equating participation with putting a cart at the curb, regardless of the quantity or quality of it’s contents.

Those who, for whatever reason, do not put a cart out on the curb could be deemed non-participants.

Those who put out an empty or almost empty cart would be considered participating.

Crazy as that sounds, that’s my take on it.

I guess the other way to view poundage per household is that the goal is to buy less stuff that you have to then recycle.

Do they weigh recycling AND landfill-bound waste? This would give us a handle on how much waste and what percentage is recycled.

And I still think the incentive system is dumb.

The main win I see is that they’ll take #5 plastic. The implication in this article is that they will accept #6, e.g. polystyrene.

Why is it they can take the unrecyclable plastics (all the way up to #7) with single stream? When did there get to be a use for the stuff?

I would bet that in my neighborhood, OWS, the amounts of recyclables sent to the MRF is less per household than other parts of the city. So by my reckoning, participation would be high and the total truck weights less from my own and similar neighborhoods.

Other neighborhoods where residents are not as enthusiastic about the three R’s could have lower participation, sending less to the MRF while continuing to send more potentially recyclable trash to the landfill.

It seem strange to have a system that has the potential to reward those who strive to consume and send less to the MRF and equally reward those who consume more stuff and send it to the landfill and the MRF.

Because of the rewards system, I suspect there will be a lot of empty or mostly empty carts being picked up every week in the neighborhoods where people take the three R’s seriously.

The neighborhoods and individuals who are not as serious will most likely continue to be non participants and continue to consume and send to the landfill and the MRF more of the stuff that we’re trying to keep from going there.

I don’t take out my recycling bins when there’s only one or two containers in there (and we recycle everything we can – some weeks there just isn’t that much – an even BETTER result for the environment). Are they telling me I’m going to get a slap on the wrist for waiting until the bin is full?

Clearly the intention here is to spend money, rather than to spend money wisely.

Maybe I’ll cut out my RFI tag and tape it to one of my more wasteful neighbors’ bins.

We also do not put out out recycle bins every week. If they are not full we wait until next week and save the truck from having to stop this week. So, sometimes we would be “non-participating”. I’m skeptical about the incentive program. I am unclear what the “rewards” are. There was a mention of coupons. Coupons for what? What is the Greenschools program?

I suggest that everyone cut out the RFI tags and send them to Sue McCormick. The cost of the “rewards” program is wasted tax dollars on top of an unnecessary new program at a time we can’t afford to fix a bridge.

Of course we’ve already paid for it and took the consultants at their word without actually thinking through it’s long term effects or dissecting the one sided information that was presented to council.

Sounds like the city has some newfangled gizmos the people aren’t sure they want.

Will Rogers used to say:

“Just be thankful you’re not getting all the government you’re paying for.”

I think it will be difficult to get an accurate comparison of cities. Assigning a value judgment to any comparison is even more difficult.

The first question is whether the weight of materials is just from residential collection, or all collection divided by total number of households. Including some or all of the commercial materials would certainly increase the amount per household in all categories but probably result in a lower percentage of recycled material.

The demographics will also have a significant effect. In an apartment building the average number of occupants in a household is likely to be less than in a suburban region. I don’t see any reason to say a 4 person suburban household that discards and recycles twice as much as 2 person urban one is better or worse.

I agree with the many comments that it is unfortunate that the City Council continues to waste money on unnecessary and undesirable pet projects like single stream recycling and especially the Recyclebank program. It simply seems that the majority of council do not believe that the city has any financial problems.

I am uncomfortable with the idea that city hall – or some corporate entity – “would know exactly which households were not participating in the program.” I do not want this intrusion into my privacy, in my home.

Did anyone mention the effect that single-stream mixing of materials has on the recycle-ability of the materials collected?

I would be absolutely thrilled to see a 200% increase in volume, but let’s see a report semi-annually on this, please, not just a few years from now. And if things aren’t looking up quickly, let’s off-load these fancy trucks on one of RecycleBank’s next suckers.

“Nothing is easier than spending public money. It does not appear

to belong to anybody. The temptation is overwhelming to bestow

it on somebody.”

–Calvin Coolidge (you know, from back when “they” had ideas)