“It Looks Like a Great Burn Day”

Like many articles in The Chronicle, this one begins at a public meeting. But unlike any others, it ends in a partially burned woods at Argo Nature Area, where a crew clad in yellow fire-retardant suits kicked up puffs of smoke as they strode through the ashes of their work.

Gear for a member of the city's Natural Area Preservation burn crew, on the stoop of the Leslie Science & Nature Center. (Photos by the writer.)

On the path from one to the other, we learned about sling psychrometers, drip torches, council rakes and what kind of leaves burn best. Our guides were the staff and volunteers of Ann Arbor’s Natural Area Preservation program, who will be wrapping up the spring burn season later this month.

We first got an overview of the city’s controlled burn program from NAP’s manager, Dave Borneman, who made a presentation about it at the February meeting of the Ann Arbor park advisory commission. He described the ecological rationale behind a burn, citing the benefits it brings by controlling invasive species and rejuvenating the land.

As it turns out, Borneman was also the “burn boss” when we tagged along on a burn last Friday – the first one done by NAP in Argo’s lowland area.

But the day for the crew began at their offices in the Leslie Science & Nature Center building, on Traver Road – so that’s where we’ll start, too.

Will Today Be a Burn Day?

Because of consistently dry weather – a trend that’s been disrupted this week – this spring has been a remarkably good one for controlled burns. The last week of March and the early days of April leading into Easter weekend were shaping up to continue the streak – on April 1, dozens of spectators showed up for the popular annual burn at the Buhr Park Children’s Wet Meadow, which went well.

By Friday, though, as the NAP staff gathered for their morning meeting, the National Weather Service had issued a “red flag warning” for southeast Michigan – an indicator of “critical fire weather conditions.” And because dry, hot weather made the spread of fire a risk, the state’s Dept. of Natural Resources and Environment stopped issuing burn permits.

NAP has a blanket permit for its controlled burns from Ann Arbor’s fire marshal, covering the spring and fall seasons. Even so, the fire marshal gets to make the call on any given day – checking in with the fire marshal is part of NAP’s protocol before doing a controlled burn. On Friday, there was a period of uncertainty, as the burn crew waited to hear back about whether they’d be allowed to proceed.

Uncertainty is part of the drill. Even if the weather forecast looks solid, conditions might change overnight. So the burn/no burn decision is made in the morning, following a series of checkpoints made by staff.

On Friday, Tina Roselle walked The Chronicle through some of those checks from NAP’s second floor offices in Dr. Leslie’s old homestead, where the Leslie Science & Nature Center is also located.

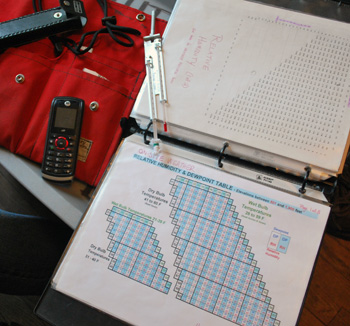

A weather kit, including this chart to help calculate on-site humidity, gets packed for the burn crew to take out into the field.

Roselle is coordinator of the city’s Adopt-a-Park program, but during burn season she often spends the morning doing prep work for the crew. Next to her desk is a large plastic tub, which she is filling with supplies:

- Extra water bottles.

- Medical forms and sign-in sheets for volunteers.

- A plastic bag crammed with Oskri bars – they’re good because they’re vegan, organic, gluten-free and edible by people who have food allergies, Roselle says. Other snacks are in the tub as well, including crackers and peanut butter creme cookies. (Roselle also walks across the office and pulls back a curtain to reveal shelves full of additional snacks – more fuel for the volunteers and staff.)

- A red cloth pouch with several tools for checking the weather, including a Kestrel 3000 wind meter, a compass to identify wind direction, and a sling psychrometer to measure humidity on site.

Roselle also checks a range of weather conditions so that the crew can know what to expect out in the field. She calls a number at the Ann Arbor municipal airport – 734-668-7173 – that gives a recording of wind speed and direction, temperature and other conditions specific to the city. She prints out a report from the National Weather Service website for the Ann Arbor area – the site includes hourly forecasts for humidity, precipitation, wind gusts and other measures.

Wind speed and direction are important, as those indicate how the fire might burn, and how smoke from the burn might affect surrounding areas. Those conditions factor into the selection of the burn site on any given day.

Humidity is another factor, because it generally predicts the dryness of the oak leaf “litter” or grasses, which fuel the burns. Since humidity is typically lowest around midday, most of the burns begin at noon.

Part of Roselle’s job can’t be done until the burn crew emerges from their morning meeting, where they discuss which sites to tackle out of a master list that’s been compiled for the season. Depending on weather conditions, the number of people available and the size of the burn sites, up to six locations might be handled in a day. Typically, though, the crew usually tackles one or two larger sites.

On Friday, there was just one burn – at Argo. So Roselle pulls a “burn prescription” for that location. These extremely detailed reports are prepared for each potential site in advance by NAP staff, with some information to be completed on the morning of the burn. Essentially it’s a how-to sheet, listing the location of the site, how to get there, who owns it, where the nearest water source is, and who needs to be notified about the burn – including a list of contact information. It also includes burn objectives – in the case of Argo Nature Area, the main goal is to kill garlic mustard, an invasive plant species.

There are also details about smoke management, one of the more important elements of a burn in terms of potential impact on the surrounding community. A smoke management plan might look something like this, taken from a sample burn prescription for Cedar Bend Park:

1) Conduct burn when atmospheric conditions allow for maximum lifting, mixing and transportation.

2) Create burn breaks around dead snags, chimney trees, stumps, logs brush piles to prevent burning.

3) Attempt to have the burn and mop-up completed prior to rush hour traffic.

4) Make sure nothing is left smoldering when we leave the site.

5) Schedule burn during weekdays when fewer people on-site or in nearby homes.

[.pdf file of a sample burn prescription for Cedar Bend Park]

After getting the good-to-go signal for the day, Roselle makes calls to the contacts specified in the burn prescription. She also sends out a mass email to volunteers, giving details about when and where the day’s burn will occur. Media outlets get an email too, and word goes out over NAP’s Twitter and Facebook accounts. [To sign up for alerts about controlled burns or other NAP activities, email nap@a2gov.org.]

It takes at least an hour – usually more – to make all the contacts, Roselle says.

Pre-Burn Prep Work

Meanwhile, other NAP workers are getting together equipment and supplies for the day. On Friday, we found Steven Parrish in a basement workshop, sharpening tools. He nicked his finger on a pulaski, a combination axe and mattock. “I did a good job sharpening that,” he deadpans, sucking on the blood.

Steven Parrish, a conservation worker with the city's Natural Area Preservation program, sharpens a pulaski that will be used in a controlled burn.

Shovels, picks, council rakes, chainsaws, two-way radios – all manner of tools and equipment are stacked in this basement storage area, where lockers for the crew are also located. The lockers are used to store each person’s burn crew suit, issued for the season – either a one-piece jumpsuit or pants and a jacket, made of heavy yellow fire-retardant material. In the same way that the brand name Kleenex has taken on a generic meaning, the suits are called Nomex – a brand name that’s commonly used to refer to any fire-retardant suit. (And unless they get particularly nasty, the suits are washed only at the end of the burn season.) Each crew member also has a yellow helmet with plexiglass visor – on the front, their name is written in large letters on yellow duct tape.

Part of the prep work includes making sure all the equipment is ready, Parrish says. In addition to sharpening tools, he’s already repaired the metal frame on a backpack that holds a metal water tank.

Most of the other half-dozen workers are elsewhere on the grounds. Some have gone to the nearby Leslie Park Golf Course to fill up the tank on the water truck. Others are loading a large red trailer – among its contents are several signs that will later be placed on roads around the area of a burn, to alert residents and drivers who might spot the smoke. The trailer also holds orange road cones, leaf blowers used to create a break around the perimeter of the burn, blue plastic tubs filled with fire-retardant suits in an assortment of sizes for volunteers, and a hodge-podge of tools.

Up the hill, Robb Johnston has driven a pickup truck to a storage shed and is hoisting five-gallon red and blue metal canisters of fuel into the truckbed. The crew uses fuel for its chainsaws and for pumps on the water trucks.

He’s also loaded 11 drip torches – smaller canisters with long nozzles that are carried by the burn crew and used to light the fires. The drip torches are filled with a cocktail of kerosene and gasoline in a four-to-one ratio – instructions for the mix are scrawled in marker on the inside of the shed. Johnston explains that kerosene makes for a sustained burn, mellowing out the more explosive gasoline. Explosiveness on a controlled burn is not good.

At the Burn Site: Getting Ready

By 11:30 a.m., a pickup truck with NAP’s distinctive red trailer is already parked in the lot near the entrance to the nature area. Laura Mueller has opened the trailer door and unloaded the blue plastic tubs with gear for volunteers, along with several of the water-tank backpacks and a tub of snacks.

In part because of the Good Friday holiday, there’s a fair amount of activity – kids playing across the road in Longshore Park, joggers, dog-walkers, fishermen, people driving in and unloading their canoes and kayaks. A couple of geese waddle along the shore, honking. Across the Huron River, an Amtrak train rolls by.

A sign is already posted at the head of the trail where you enter the woods, stating that the nature area is closed. Throughout the afternoon, this is routinely ignored – and that’s pretty typical, according to the burn crew. When working in the urban parks, it’s common for people to go through a burn site, and there’s not much the staff can do about it.

Volunteers for the controlled burn get into their gear in the parking lot next to the Argo Nature Area.

Volunteers begin to arrive. The first is Gracie Holliday, an undergraduate at the University of Michigan. She’s been a NAP volunteer for other projects, but aside from the training that all volunteers must complete, this is her first burn. A petite woman, she roots through the tub marked “S” to find some gear that fits – sort of.

By noon, about a half-dozen other volunteers have arrived, coming by bike, motorcycle and car. They also gear up, though at least one man – Jim Hope, who’s also a firefighter – wears his own suit. In general, volunteers are asked to wear their own leather boots, but are provided everything else, including well-worn leather gloves and two-way radios that are clipped to the front of their jackets. They pass around a clipboard to sign in. Some have brought their own lunch, but others grab a snack from the tub provided by NAP. Amanda Nimke passes out clementines.

Dave Borneman shows up – he’s parked the burn trailer for his private business in a parking lot down the road. He’s the “burn boss” for the day, and consults with Lara Treemore-Spears, a NAP technician who’s also supervising the site. Other staff prepare the drip torches, fill water tanks, and help volunteers get into their gear. A couple of kayakers ask Mueller to take a photo of them before launching their craft into Argo Pond – she obliges.

Staff and volunteers get briefed on the upcoming burn, standing in the parking lot at the Argo Nature Area.

About a dozen people – staff and volunteers – are in their full gear when Borneman asks everyone to huddle up. They form a circle, and make introductions. Borneman passes out maps of the area, and talks about conditions for the day – it’s dry, he says, with high temperatures and wind creating a greater chance for fires to start and spread, “which is why we’re not in a cattail field.” He clarifies that there’s not a burn ban in effect, and that the fire marshal has given the go-ahead for their work. Even so, Borneman says he wouldn’t be surprised to see a fire truck cruise by during the afternoon. “We’re going to avoid every opportunity for them to shut us down,” he says.

Borneman notes that two people from NAP’s staff will be driving around the neighborhood, monitoring smoke. Smoke monitoring will be especially important today, he says: Because of the holiday, more people will likely be at home and outside, and because the weather’s nice, homes in the area are more likely to have their windows open. He notes that the gray overcast sky works to their advantage, masking the visible signs of smoke so that residents won’t get concerned.

Borneman tells volunteers that they’ve never done a controlled burn in the lowland area of the Argo Nature Area, and he included a bit of a pep talk: “It’s going to be a great burn day!” He cautioned them to try to burn around the patches of trout lilies, bloodroot and other wildflowers they find. This is done by dousing the flowers with water just prior to the burn. It’s an effective strategy.

In wrapping up, Borneman urges the volunteers to make sure they drank plenty of water – everyone needed to carry a water bottle. When they return to the base to refill the water tanks on their backpacks, he said, be sure to grab something to eat as well. “Expect to be really hot and tired and sweaty,” he said.

They then quickly divy up tasks. Four volunteers are chosen to ignite the fires with drip torches – this seemed to be a coveted job, and volunteers were picked who hadn’t done any igniting recently, or in the case of Holliday, ever.

Parrish gives an on-site weather report, which would be updated every hour: 72 degrees, with relative humidity at 45% and wind from the south. Borneman does a radio check, making each person could receive and transmit clearly.

And with that, they flip down their visors and get to work.

Volunteer Jim Hope fills the water tank on his backpack. The tank on the truck holds 300 gallons. The tank on the backpack holds four gallons – with a full water tank, each backpack weighs about 40 pounds.

Two volunteers in fire gear spray water on the Argo Pond boardwalk, prior to burning the surrounding brush.

Along the banks of Argo Pond, volunteer Gracie Holliday ignites some brush while NAP's Laura Mueller sprays water on the smoldering ashes.

In a slight blur of smoke from small burns along the edge of Argo Pond, crew members enter the woods at Argo Nature Area.

It is amazing that the City of Ann Arbor will pay people to set fire to their parks but doesn’t want to pay people to put out fires in their buildings. No wonder AA is the laughing stock of surrounding communities. How may other communities in S.E. Michigan pay people to burn up their parks?

Dude… You pay for them to burn the parks. They are millage funded, which means that the tax payers have voted to tax themselves to pay for this. This is why the natural areas in AA are so sweet. We have a community who understands environmental/ecological issues enough to pay for the health of these places. And I’m not sure, but I’m guessing those people get paid a fraction of what the fire department does. Maybe someone could find out. I would guess its many of millions, to less than a million.

Check yourself before you wreck our town.

Most of these people are volunteers, so the cost to run this program is small in comparison to your police and fire departments. I am sorry that you have such disdain for maintaining a diverse and healthy natural environment, johnboy.

Mary,

Thanks for an article that points out the hard work that goes into keeping natural areas, well, natural. Ann Arbor Natural Areas Program has an admirable and well deserved reputation for stewardship on the lands they manage.

The article does a great job of describing the details of the burn process. It would be great to do a follow up article describing the reasons for controlled burning: control of invasive species, and the results of such work. Retaining our native species diversity of plants, insects, birds and mammals is key, and information from our local experts will be a great contribution to community understanding and support of the NAP. The burn efforts help reduce buckthorn, garlic mustard, honeysuckle, and other invasives that ultimately crowd out our beautiful native plants (such as the bloodroot pictured). Maintaining diverse plant life supports native insects and wildlife, our unique heritage and environment.

I would like to point out that NAP does many other things with the money that the taxpayers have voted to give them. Most of the things they do fall under the category of ecological restoration, such as herbaceous invasives removal, brush removal, prescribed burning, and monitoring of vegetation and wildlife in the parks. In addition, they remove trees over trail, do trail maintenance and construction, locate hazard trees for the forestry department to remove, and lead educational programs. While doing all of this, they leverage a small, mostly temporary seasonal staff, with many many hours of volunteer help. While some people may not agree with the ecological importance of our city parks, NAP is also responsible for upkeep and access to all city ‘natural areas’, basically any city park portion that’s not mowed. And I feel that it’s totally worth it to have many beautiful places to bike, walk, and run in.

It’s cool; it’s what the native Americans did to keep the underbrush down and more walkable as well as better for hunting, they kept this area looking like a prairie park with big oaks I was taught.

Dude – The NAP division is a waste of tax dollars. It has nothing to do with keeping out parks natural or preserved. It is just there to follow the latest eco-fad in a very trendy and fad oriented town. The only true “invasive species” is the two legged one that goes into our parks and plays God by tearing out non-politically correct plants and then setting fire to what is left.

If you want natural parks then STAY OUT of the parks. Mother nature can restore a park all by herself. Just leave her alone. Please explain to me how pulling up dozens of non-PC plants increases diversity. IT IS NATURAL for a specific species of plant to dominate an area that is favorable to it’s growth requirements. Undergrowth is NATURAL. Burning it off is UNNATURAL.

Many of the so called “invasive species” were actually brought over here from other continents to increase our diversity. You don’t increase diversity by eliminating species.

Anybody who took Biology 101, and paid attention, knows that attempting to eliminate and one species in an area that is surrounded by that species is simply a waste of time and tax dollars. Lets say that by some magic (or great expenditure of tax dollars) you pulled up every garlic mustard and buckthorn plant in Ann Arbor. What would happen in 3-5 years? Thanks to the birds and wind, all the garlic mustard and buckthorn would be right back where it was growing before. “Invasive species” in an eco-fad.The only true “invasive species” are human beings. Dude

OK, OK, as much as it hurts, I’ll have to admit NAP DOES some good things like monitoring and recording vegetation and wildlife also trail maintenance. But I wish they would stick to the really constructive programs and stay away from eco-fads.

Clearly anybody who took Biology 101 would learn a great deal about the proper use of tax dollars. Um, yeah.

But anybody who took any more advanced biology would know that the greatest threats to biodiversity are:

1) Habitat destruction

2) Invasive species

I think you should do a little experiment. Bring a little Garlic Mustard into your back yard, into your prized garden bed, let it ‘naturalize’, and then tell me how much more ‘diversity’ you have in 5 years. After 15 years, when your neighborhood flora has been destroyed by this “non-PC plant” and all the butterflies and birds you used to like are gone, I will come over and help you remove the mustard from your hood and begin the healing process.

Speaking as someone who studying ecology and has worked in the field, I can tell you there is a good reason that invasive species are compared to cancer. And not something like prostate cancer. More like a metastatic melanoma. They spread, they spread fast, and if you don’t catch it (them) early, it is next to impossible to get rid of them.

As if the Emerald Ash Borer has increased diversity

As if the Asian Carp has increased diversity

As if Kudzu has increased diversity

More species at any given moment does not equal more diversity.

And yes, us Bi-peds are a fine example. There indeed are too many of us. But it is our hands off approach to nature, thinking that we are outside of nature, that is causing most of the problems. We, as a culture, can’t grasp that we are completely a part of what goes on outside, whether its habitat conversion to subdivision, the spread of aggressive non-native plants, or simply driving our cars too much.

You John-Boy, are part of the ‘natural’ processes that are taking place if you want to acknowledge it or not. You can make the decision to make a difference and defend our natural areas, or continue to use your Bio101 knowledge and let the world change for the worse, without your input. I hope you choose to learn more.

[link]

[link]

[link]

Anybody knowledgeable to speak to the CO2 greenhouse gases implications associated with burning?

What would be natural would be periodic, uncontrolled, spontaneous fires from lightning strikes or other sources. I don’t want that in my neighborhood, so planned, controlled, low-level burns are a great alternative.

I’m not sure on the net CO2 impact, so I don’t qualify as the “knowledgeable” voice that Pete asked for, but I wouldn’t be surprised if these burns were carbon-negative due to increasing the growth of larger plants that store more carbon. Anyone know for sure?

RE: CO2 emissions, this article is talking about grassland burning, so it might not address your question 100%, but it will help: [link]. It’s a fairly easy read, but has good citations and solid science behind its reasoning. Bassically, the paper suggests that Chuck’s supposition is dead on. The burns stimulates the growth of prairie grasses by removing dead grass that would inhibit growth, allowing grasses to grow quicker and longer. While there is a release of CO2 into the atmosphere, the grasses are able to sequester more carbon than is released by a significant amount. Interestingly, the author notes that trees do NOT sequester carbon

Chuck is also correct that lightning strikes would be one way for “natural” burns to occur. In a given ecosystem, fires can occur at fairly regular intervals, and any resulting fires are generally “cool” fires. Many tree species have adapted to this pattern, and some, such as the Jack pine, are wholly fire dependant for reproduction. Our fire repression regime, on the other hand, allows brush build up so that when a fire eventually does happen, either through arson or more natural causes, the results are catostrophic (think the California wildfires of a couple years ago).

Finally, Johnboy clearly doesn’t know his history very well. Far from being “eco-fads”, controlled burns have been used by civilizations around the world for thousands of years. It’s only been in the past hundred years or so that fire repression has become the norm, and anyone who has taken an advanced ecology course knows the benefits.