Building a Sustainable Ann Arbor

About two dozen members of three Ann Arbor commissions gathered last week for a rare joint meeting, a two-hour, wide-ranging discussion focused on the issue of sustainability. Bonnie Bona, chair of the city’s planning commission, said the working session was meant to start a conversation, with the goal of moving the city toward a sustainable future.

From left: David Stead, Jean Carlberg, and Fulter Hong at an April 13 working session on sustainability. They are members of the environmental, planning and energy commissions, respectively. (Photos by the writer.)

The discussion touched on the conceptual as well as the concrete, with some commissioners urging the group to tackle practical considerations as well. The chairs of each commission – Bona, the energy commission’s Wayne Appleyard, and Steve Bean of the environmental commission – set the stage by talking about the roles of their appointed public bodies, and how sustainability might be incorporated into their work.

Specific ideas discussed during the session included financing energy improvements in households through a special self-assessment on property tax bills, and tapping expertise at the University of Michigan.

More than midway through the meeting they were joined by Terry Alexander, executive director of UM’s Office of Campus Sustainability. He described UM’s efforts at implementing sustainable practices on campus as well as creating a living/learning environment for students, teaching them what it means to be a “green citizen.”

Toward the end of the meeting, Bona noted that the issue extended far beyond the three commissions gathered around the table. Housing, parks and other areas need to be involved as well, she said, if they were truly to tackle the three elements of sustainability: environmental quality, social equity, and economic vitality. Bean said he and the other chairs would be meeting again and come up with some specific examples for what steps might be taken next. “You’ll be hearing from us,” he said.

Planning, Energy & Environment: An Overview

Bonnie Bona began the discussion by describing the work of the planning commission, which she chairs. They’re responsible for the master plan and ordinance revisions related to planning, and work on a raft of issues through standing and ad hoc committees, including area, height & placement standards, capital improvements, and R4C/R2A zoning districts, among others.

Bona said she’s been thinking about the concept of sustainability for several years, and the questions that it raises. For example, what’s the sweet spot for building height and density, to create a sustainable community? In her work on the area, height & placement committee, each time they’ve gotten comfortable with a certain level of density, they’ve asked: Why not push it a little more? Bona said she doesn’t know what optimal density is, but she’s feeling less and less comfortable relying on political winds, and not having a way to measure it.

Beyond density, she said they haven’t been considering the other elements of sustainability – economic vitality, and social equity. These are broader issues that encompass more than just planning, she said. A more productive way to move forward would be to take a comprehensive look at what it means to be sustainable. “And that is how I got here,” she said.

Energy Commission

Wayne Appleyard, who chairs the energy commission, said the group was trying to help meet the city’s green energy challenge, set in 2005: To use 30% renewable energy in municipal operations by the year 2010. He noted that the deadline is coming up quickly. The goal for the entire community is 20% renewable energy by 2015.

City government is close to meeting its goal, Appleyard said, with its “green fleets” program using alternative fuel vehicles, electricity generated from landfill gas and two dams on the Huron River, and other efforts.

For the broader community, the commission is exploring the PACE (Property Assessed Clean Energy) program as a way for homeowners to finance energy improvements, like installing a solar energy system. [Matt Naud, the city's environmental coordinator, explained the program in more detail later in the meeting.] Other possibilities include requiring time-of-sale energy audits, so that potential homebuyers could wrap funding for energy improvements into their mortgage; educating the public about renewable energy and energy efficiency measures; and figuring out how to generate more electricity from dams on the Huron River.

Appleyard also discussed what it means to be sustainable. Often it’s considered as meeting our needs today, without harming future generations. It takes into account both economic and social aspects as well. He quoted William McDonough, author of “Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things,” in describing the outcome of sustainability: “a delightfully diverse, safe, healthy and just world, with clean air, water, soil and power – economically, equitably, ecologically and elegantly enjoyed.”

Achieving these goals means redefining everything we do, Appleyard said. Sustainability means you have to account for everything you do, and do things only that make sense for all three areas: environmental, economic and social.

Environmental Commission

Steve Bean described the work of the environmental commission as advising the city on issues related to the environment and sustainability. The group has six committees: natural features, solid waste, water, transportation, State of Our Environment, and sustainability community. Ad hoc committees include recycling and the Huron River and Impoundment Management Plan (HRIMP).

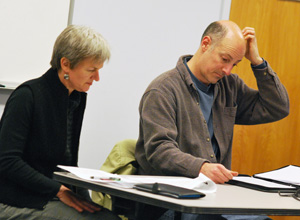

Bonnie Bona, chair of the Ann Arbor planning commission, and Steve Bean, who chairs the city's environmental commission.

The sustainability committee is taking a three-phase approach to its work, Bean said: 1) looking at what the city does now that isn’t sustainable, 2) developing an environmental action plan to show how to work toward their goals, and 3) broadening the goals to include elements of the economy and social justice.

The sustainability committee has also been working with the Transition Ann Arbor group, Bean said. [See Chronicle coverage: "Transitioning Ann Arbor to Self-Reliance"] That group is focused on transitioning the community in light of an end to cheap oil – known as “peak oil” – climate change and economic instability. One aspect of their plan is to build bridges to local government, Bean explained, so the sustainability committee offered to serve that function. They’ll be talking about how the Transition Ann Arbor plan meshes with the city’s efforts toward sustainability.

Bean also said he felt that the term “sustainability” was used too loosely: Something is either sustainable, or it’s not.

Starting the Discussion: Some Questions

Bonnie Bona began the more general discussion by posing four questions: 1) Where are there opportunities or overlap for pursuing sustainability among the three commissions? 2) What are the constraints? 3) Should they measure progress? and 4) Is there consensus toward a way of moving forward, or a goal?

The three commission chairs have been meeting regularly and will continue to do that, Bona said. There are also things that can be done informally. But she wondered whether there was any interest in forming a joint steering committee on this issue, or pursuing a community-wide discussion.

Commissioners Weigh In

Planning commissioner Jean Carlberg, a former city councilmember, began her comments from a personal perspective: How can she heat her house and get electricity in an energy efficient, cost-effective way? She pointed out that what she has to do individually is exactly what every city has to do on a larger scale. How can they develop pathways to move away from reliance on oil and natural gas?

Wayne Appleyard said that you start by making energy efficiency changes in your home, because those are the cheapest. Payback on your upfront costs is always an issue, he said. “And I’m convinced the future isn’t going to be like the past, so payback is harder to predict.” Once you reduce energy costs as much as possible that way, you can start looking at renewable energy to meet your needs, he said.

Steve Bean noted that the PACE program is one potential way for homeowners to fund energy improvements. John Hieftje, the city’s mayor who also serves on the energy commission, said that he, Mike Garfield of the Ecology Center, Ann Arbor energy programs manager Andrew Brix and Matt Naud, the city’s environmental coordinator, have visited Lansing to meet with legislators, asking them to approve the enabling legislation needed to make PACE possible.

PACE: Property Assessed Clean Energy Program

Naud gave a more detailed explanation of the program, saying that several other states have enacted legislation to support it. He explained that while there are programs available for low-income homes – like the county’s weatherization efforts – it’s more difficult for people at middle-income levels to find resources. Banks aren’t lending, he said, so there’s a gap in how to pay for upfront costs to make your home more energy efficient.

The program would be voluntary. Homeowners would first get an energy audit to find out if they’ve already taken initial steps on their own – for example, Naud said, you wouldn’t want to install solar power if you haven’t sufficiently caulked around your windows. You’d sign a contract with the city, which Naud said would microfinance the improvements. To repay the loan, homeowners would get an additional assessment on their property tax bills.

The risk is low, Naud said, as long as they structure the program in the right way – for example, not lending to people who are upside down on their mortgages, owing more than the home is worth. There’s already a system in place to make payments – the tax bills – and the improvements would add value to the property. The city has set aside $400,000 from a federal Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant it received, to use as a loan loss reserve fund. If the enabling legislation is passed, the city would be able to put together a package that would work, Naud said.

[Link to a September 2009 article about the PACE program, written by Eric Jamison, a law student at Wayne State University Law School who's working with the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center to develop the program in Michigan. More information is also available on the PACE Now website. Previous Chronicle coverage related to PACE: "Special District Might Fund Energy Program"]

Other Thoughts: Regionalism, Economic Impact, Trees

Mayor Hieftje said that talk of sustainability can’t just stay within the city’s borders. It’s important to look at it regionally, as the city has done with the greenbelt program, the Border-to-Border trail and transportation, including efforts to develop a commuter rail system. What is Ann Arbor’s responsibility to other communities, he asked. Also a factor – thousands of new jobs are expected to be added in this area in the coming years. “It’s a big issue, and I don’t think we can talk about it within city borders and do it justice.”

David Stead of the environmental commission said the Ann Arbor region should be looking at the issue of sustainability as an economic development tool. Michigan is going through dramatic change, he said, and Ann Arbor is at the epicenter as the state shifts from an industrial economy to whatever comes next – possibly clean energy. “We can be the model and the driver for that,” he said.

From left: Chuck Hookham, Josh Long, and Diane Giannola. Hookham and Long are members of the Ann Arbor energy commission. Giannola is a planning commissioner.

Valerie Strassberg, also on the environmental commission, said it was difficult to know where they were going without knowing where they were now. This community is different from Berkeley or Portland or Seattle, she said. What are lifestyles like now in Ann Arbor, and how much would they need to shift to be sustainable?

Josh Long of the energy commission talked about the continuum of how to get energy, from efforts by the individual homeowner, which are easier to control, to the energy provided by large utilities. Large-scale energy generation is more cost effective at this point, but when it’s transmitted over long distances, some energy is lost. The sweet spot might be generating energy on a regional or district scale, but there are legal constraints to doing that.

Tony Derezinski, a planning commissioner who also represents Ward 2 on city council, said he’s interested in distributive justice – making sure the community’s benefits and burdens are spread equitably. Congress has dealt with health care, he said – what about energy, or water? How you do it is the trick, he said.

Erica Briggs, also on the planning commission, wondered what exactly they want to sustain in the community, and regionally. There’s talk about sustainability in the Washtenaw Avenue corridor, but what does that actually mean? When you start looking at it in detail, she said, it’s difficult. Briggs gave the example of her own house, which she described as an “energy hog.” Even though she loves it, she said it probably shouldn’t have been built.

Gwen Nystuen – who serves on both the environmental commission and the park advisory commission – said she wanted to put in a “big word” for trees. Trees are an important component of sustainability, helping in water protection, for example. The type of tree as well as its location should be considered carefully, she said.

Keeping It Real: What Does This All Mean?

Eric Mahler of the planning commission was the first to raise some concerns about the conceptual nature of the conversation. When evaluating a site plan, he said, “it’s hard to think of distributive justice.” He disagreed with Steve Bean’s earlier statement that sustainability was an all-or-nothing concept, and said he didn’t feel the group had reached a consensus about what it means to be sustainable.

Mahler also raised several questions: How does sustainability intersect with historic districts, or design guidelines? Does the city have the option of regulating building materials, with an eye toward sustainability? What are the city’s enforcement capabilities? He urged commissioners to think about the issue in terms of their clearly defined roles. “I wish I had answers for you, but I just have questions.”

Steve Miller of the energy commission had similar concerns, saying he was disappointed by the lack of specifics in the discussion. As he listened to the high-level talk, he said he had no idea how to apply it to goals that they might have a chance of achieving. For example, the city is pursuing a program to install LED lights, he noted, but it’s not clear whether that technology is sustainable in the long haul. In 2025, will LED lighting be the best choice? And discussions of regionalism didn’t seem to take into account the legal constraints they were working under, he said. He wasn’t hearing a lot that would help move some of these issues forward.

Planning commissioner and former city councilmember Wendy Woods described the discussion as great. “But I’m sitting here thinking, ‘Now what or why am I here or what am I supposed to do?’ I’m sure the public is out there wondering too.” All of the commissions are advisory to city council, she noted, and all have long lists of tasks that they’re working on. Is the goal to simply define what sustainability is?

Bean said this was the kind of feedback they wanted. The organizers were just interested in starting a discussion, and seeing where it goes. If they don’t reach consensus, he said, at least they might have a sense of what steps to take next.

Margie Teal, a Ward 4 representative on city council and a member of the environmental commission, said there seem to be answerable questions that can be tackled by the planning commission, like how the city’s area, height and placement (AHP) standards interface with density. “I welcome them digging in and pursuing that,” she said.

Evan Pratt of the planning commission said he liked the overarching goals that the energy commission is working toward – of 20% and 30% renewable energy use – and the goals that the environmental commission is tracking through the State of Our Environment report. From a policy perspective, planning has a role to play, too, in furthering sustainability goals. “It’s pretty clear that some change is necessary,” he said. Pratt suggested identifying common goals that each commission can work toward.

Bean said he thinks of sustainability as a filter that each group can apply, asking how each policy or project they deal with affects the environment, social equity and economic vibrancy.

Dina Kurz, a member of the energy commission, noted that all the commissions are advisory to city council, and that there are areas where their missions overlap. For example, the energy commission has discussed solar access zoning – that’s clearly a relevant topic for the planning commission, too. She said she doesn’t believe that sustainability can be just a city-driven effort, but that they can only change the things that they control. They need to figure out what those things are, she said, and how to leverage their partners to move forward.

Sustainability: The University Perspective

Terry Alexander attended Tuesday’s meeting to give an update on initiatives at the University of Michigan. He was appointed as director of UM’s office of campus sustainability last year – The Chronicle had previously encountered him at the December 2009 board of regents meeting, where he described sustainability initiatives underway on campus.

On Tuesday, Alexander gave a similar presentation, though he had exchanged his suit and tie for more casual garb. He told commissioners that UM president Mary Sue Coleman hoped to make the university a world leader in sustainability, and to develop a living-learning environment for students. UM touches the lives of 40,000 students each year, he said – if they leave campus with even a little awareness about sustainability, they’re the ones who will go out and change the world.

The Executive Sustainability Council – led by Coleman and consisting of many of the university’s top executives – sets broad policy and goals for the initiative. The academic and research efforts are led by the Graham Environmental Sustainability Institute. Some of that entails recruiting faculty with interests in sustainability, who can attract research dollars, Alexander said. He pointed to the Erb Institute and the Michigan Memorial Phoenix Energy Institute as other examples of sustainability-focused research. There are also about 50 student groups on campus that have a sustainability component – the Graham Institute is trying to coordinate those efforts, too.

Alexander described his own office’s mission as three-fold:

- Establish long-term “stretch” goals for the university. UM has been doing things like conserving water and energy for years, he said. Now, they need to come up with goals that will change the way people think about things on campus. They’ve set up teams to make recommendations in seven areas: buildings; energy; land and water; transportation; purchased goods; food; and culture (changing people’s attitudes). Alexander said they hope to have goals set by later this spring.

- Coordinate the existing sustainability projects already underway on campus. There are over 200 projects that relate to sustainability, Alexander said – some new, some that have been around for years. His office will try to coordinate these efforts and help people find the resources they need.

- Get the word out. There’s a lot going on, but they need to communicate that to the community, state and nation, Alexander said. One of their current publicity efforts is an annual Environmental Report, a brochure that he passed out at Tuesday’s meeting. [.pdf file of 2009 Environmental Report] “If we don’t get word out,” he said, “we’ll never be recognized as world leader.”

John Hieftje, the city’s mayor who also serves on the energy commission, said the city is working with UM on a study for a possible bus connector system to run through Ann Arbor, along the South State and Plymouth Road corridors. [See Chronicle coverage: "Green Light: North-South Connector Study"] But a few years ago, he said, the city tried to partner with UM in purchasing LED lights, and he couldn’t understand why the university didn’t want to work together on that. “As we move forward, keep us in mind,” he told Alexander, adding that UM might be going over ground that the city has already covered. He noted that Ann Arbor has won awards for its environmental efforts.

Responding to Alexander’s comments later in the meeting, David Stead of the environmental commission asked how conversations at the executive level related to sustainability as a community-based function. The university doesn’t always consider its impact on the community, Stead said, adding that there’s a long history of ignoring things, like compliance with building codes. “If you’re going to do sustainability, I certainly hope it doesn’t stop at State Street.”

Alexander said it was a valid point, but he doesn’t participate in the executive-level discussions. However, he said there was a lot of interaction between the university and city staff at the planning level, including monthly meetings between the two groups.

Next Steps

Jason Bing of the energy commission, who also manages Recycle Ann Arbor’s Environmental House, said that the only way Ann Arbor would meet its goals is to link with the university and regional partners. If everyone embraces the same goals, that will allow things to happen on the ground. It had been extremely valuable to bring the commissions together, he said.

Fulter Hong, a manager at Google who serves on the energy commission, suggested setting up an online discussion group so that members could continue these efforts, rather than relying on the commission chairs. It’s a tactical approach to keeping the discussion active, he said. Valerie Strassberg of the environmental commission suggested setting up a Facebook group or a blog.

Steve Bean pointed out that the environmental commission includes representatives from other commissions, as a way to keep informed about what other groups are doing. “I’m learning it’s not a two-way street,” he added.

Matt Naud suggested that the Urban Sustainability Directors Network, which he’s active in, could be a resource.

Setting Goals: The State of Our Environment Report

Referring to the city’s State of Our Environment report, Jean Carlberg – a planning commissioner and former city councilmember – said she’d like to see someone prioritize the next steps to achieve the sustainable energy goals. What steps should be taken, at both the individual and institutional level? The planning commission isn’t the best place to do that, she said, but it seems like it’s appropriate for the energy and environmental commissions. “I’m happy to follow somebody else’s lead,” she said.

Planning commissioner Eric Mahler agreed, but suggested that perhaps the planning commission can take a small portion of the city – the South State Street or Washtenaw Avenue corridors, for example – and ask what sustainability might look like, from all three perspectives: planning, energy and environmental. He proposed that the chairs make recommendations to the rest of the commissioners about how to proceed.

David Stead of the environmental commission noted that that the State of Our Environment report was based on data. Their intent was to identify goals and metrics. He suggested that each commission could do the same. The planning commission, for example, might want to look at density and ask what are the goals, and how would they be measured.

Valerie Strassberg said there were some things she’d like to bring to planning commission. She serves on the environmental commission’s water committee, and they’ve talked about why gray water can’t be used in toilets – it might be possible to change building codes to allow that, she said.

“I’m not sure toilet water quality is in our purview,” Mahler quipped.

John Hieftje took issue with some of the environmental indicators in the State of Our Environment report. He noted, for example, that the bicycling indicator was listed as “fair,” but that Ann Arbor ranks among the top in the nation for bike-friendly communities. Steve Bean replied that the indicators reflect how the city is doing relative to its own goals, not compared to other communities.

Sustainability: Role of the City Council

Josh Long of the energy commission observed that the way government is structured is an impediment to achieving sustainability. The recent city staff reorganization, he said, reflects priorities. In the org chart, the city administrator and city council are on top, followed by budget and finance staff, then everyone else. That reflects financial priorities, but not the environment or social justice, he said. Reorganizing to elevate the status of environmental and social justice issues would be a difficult thing to do, he said, but an important one. That way the city could really start focusing on sustainability.

From left: City councilmembers Carsten Hohnke (Ward 5), Tony Derezinski (Ward 2) and Margie Teall (Ward 4). Derezinski serves on the planning commission. Hohnke and Teall are on the environmental commission.

Wendy Woods, a planning commissioner, pointed out that the city council could take action on these issues, if they had the mindset to do so.

City councilmember Carsten Hohnke (Ward 5), who also serves on the environmental commission, said that one of the themes he’d heard during Tuesday’s meeting was that for sustainability to gain traction, there’s a cultural change that needs to occur. Perhaps one way to change people’s attitudes is to translate sustainability into very direct benefits for the community. For example, if people can see that their energy bills would go down when they take certain actions, that might change their behavior.

The council talks about its priorities and goals at an annual planning retreat – Hohnke said it would be good to touch base with the chairs of these commissions before the retreat.

Finally, he noted that the local food system was another element of sustainability, and there are efforts underway to increase the amount of money that residents spend on locally produced food. [See Chronicle coverage: "Column: The 10% Local Food Challenge"]

Bonnie Bona wrapped up the meeting by noting that the issue extended far beyond the three commissions – housing, parks and other areas need to be involved as well. Steve Bean told the group that the three commission chairs would come up with recommendation for steps that might be taken next. “You’ll be hearing from us,” he said.

Present: Energy Commission: Wayne Appleyard, Jason Bing, John Hieftje, Fulter Hong, Charles Hookham, Dina Kurz, Josh Long, Steve Miller, Ken Wadland. Environmental Commission: Steve Bean, Carsten Hohnke, Gwen Nystuen, David Stead, Valerie Strassberg, Margie Teall. Planning Commission: Bonnie Bona, Erica Briggs, Jean Carlberg, Tony Derezinski, Diane Giannola, Eric Mahler, Evan Pratt, Wendy Woods.

What? No vitriolic criticism from the usual suspects who don’t want to see any city $$ spent on virtually anything, be it development or sustainable? Or the ones that don’t care for anything that comes out of the mouth of John Hieftje? Wow.

What we in Ann Arbor must realize is that our environmental and economic future is closely tied to what happens to Detroit.

“Planning commissioner and former city councilmember Wendy Woods described the discussion as great. “But I’m sitting here thinking, ‘Now what or why am I here or what am I supposed to do?’ I’m sure the public is out there wondering too.” ”

I was going to jump in and say this article sounds like the basis of a Saturday Night Live skit where people are babbling on about ‘social justice’ when people are being tossed out their homes in A2 because they can’t afford to stay here and we spend money on ugly urinal ‘art’ but I think the quotes in the article pretty much speak for themselves and make that case already.

There, Luis, ask and ye shall receive.

Hey Jack F. — if one puts their mind to it, an SNL skit can be created about anything!

Your cynicism exhausts me.

Why not appreciate the fact that there are people in our community (most contributing their time and expertise at no cost to the taxpayer!!) who are putting there thoughts into action…..on a very serious subject.

This attempt at developing a coordinated effort between City departmental endeavors is GREAT. Those behind this endeavor should be applauded.

I was surprised that no one from the Historic District Commission or the Commission’s staff person participated in this discussion. Many realize that the greenest buildings are those already standing. To leave out the existing environment and focus only on new construction seems to miss the point of recycling and reusing what we already have. The Historic District Commission works out of the Planning Commission so it is doubly surprising that these views weren’t part of the discussion. And obviously not all existing buildings are historic but that should not negate getting an opinion from those who work with older buildings.

I agree, Susan, that the connections between historic and sustainable need to be at the table to be discussed. There are arguments for and against the sustainability of historic buildings. Maintaining historic structures makes the most of the embodied energy in their components, but they are often inefficient in terms of insulation and air infiltration.

Also, with the social equity question, historic buildings are often not accessible to people with mobility impairments (on the flip side of that, often old buildings are cheap to rent). It’s complicated, and historic district folks need to be at the table to sort through those complexities.

Regarding sustainability and transportation, when the getDowntown program has surveyed downtown workers, a large number of the ones who work 1 or 2 miles from their home use sustainable commuting. The folks in Novi or Chelsea, not so much. So one of the questions I have is how to make it easier for people to live near where they work (or work near where they live). That’s one reason I think the AHP proposals have a lot of potential to positively affect sustainability.

I find myself interested by Steve Bean’s comment that “something is either sustainable or it’s not.” It’s certainly plausible that something that is not sustainable is bad, but I am wondering how sustainability fans think about timescale.

If our current strategy for creating infrastructure and using resources is “unsustainable” because too many bad things will happen in 10, 20, 50, 100 years, what about if the strategy doesn’t become “unsustainable” for 100, 500, 1000, 5000 years? Is the only “sustainable” strategy one that “lives so lightly on the earth” that it is 100% renewable?

@Luis: your comment about Ann Arbor’s relationship to Detroit is one that I would like to see repeated in every discussion of “local” and SE Michigan issues. Until Detroit and the rest of SE Michigan are integrated again, there are always going to be major structural impediments to the long-term health of the region. The plight of deteriorated urban cores v. affluent suburbs, seen in so many cities in the US (and I suppose elsewhere), reminds me of the old adage that if something seems unsustainable, it probably is…

Mr. Warpekoski

Ms. Wineberg wrote, “Many realize that the greenest buildings are those already standing. To leave out the existing environment and focus only on new construction seems to miss the point of recycling and reusing what we already have.”

This does not mention old or historic buildings at all. (Yes, she does mention the Historic District Commission but I took that to imply that someone from that group might be more likely to be the champion for the existing built environment.) It is not evident that she was using the terms ‘those already standing’ and ‘existing environment’ to be synonymous with ‘historic buildings’ or even ‘old buildings’. A building that is already standing may be just a few years old and not quite ready to be called ‘old’. Certainly also many old buildings are not historic as the Department of the Interior has standards that must be applied before a building can be declared ‘historic’.

I believe that you are already familiar with the distinctions I am pointing out but wanted to do so because very often these terms get used interchangeably when they mean very different things.

Good point, abc, that is an important distinction.

I think the historic district commission is particularly relevant in the discussions because there are potential clashes between buildings designated as historic and sustainability efforts.

For example, a property may be so poorly insulated and sealed that it would be more energy-sustainable to demolish it and build a new one, but if it is in a historic district, that would be difficult.

[This is where I would insert all the qualifiers about "specifics are important," "not trying to start a fight," and all that.]

I appreciate the comment in #7 about timescales. This whole subject of sustainability has a major need of definition and agreed-upon indicators. If a small group meets and agrees on goals, does their definition become the only meaning of “sustainable”? If this is to be a guiding principle of policy in our community, we will need a broader community consensus as to what “sustainable” means.

Terms that come to mind when I think “sustainable” are durability, quality, efficiency, productivity, preservation, rehabilitation, and the one that ties them all together: opportunity. Expansion of our built environment, consumption of resources, and population growth should not be the only ways to measure economic growth or success.

I cringe every time I hear a news report that cheerfully declares the economy is on the upswing because “sales of new homes” or “housing starts” are up. Just drive by all the vacant lots, homes and buildings in Detroit, with all that existing infrastructure (above and below ground) just going to waste, and tell me this country is on a sustainable path.

@Tom — what troubles me about the broad definition you provide is that some of the parameters are inconsistent. For example, many global companies(Amazon, Google, Wal-Mart ;-) arguably provide high-quality, durable goods or services in a way that is productikve and efficient (at least on a per unit basis) and creates new opportunities for customers, employees, and share-holders. Yet I feel sure you don’t consider them to be “sustainable.” So aren’t you really saying that “quality”, etc. are trumped by the need not to expand resource consumption? And then isn’t sustainability really about limiting resource usage?

Here is a link for more information about at least one alternative to relying solely on the GDP as a measure of success: [link]

I wasn’t intending to offer any formal definition of the word sustainable–just the thoughts that come to mind for me when I think of the term.

Incorporating sustainability into one’s consumer practices is probably at the heart of it all. As Americans, we are bombarded with a huge array of choices for nearly every purchase. The sustainability of our choices depends on an even larger array of factors.

Say I need a hammer to perform a task on my house. From most sustainable to least sustainable, some of my options might be: 1. Borrow one from a neighbor. 2. Buy a used one from another neighbor’s yard sale. 3. Buy a used one from a thrift store that I walked or rode my bike to. 4. Buy a used one from a thrift store I had to drive or take bus to. 5. Buy a new one that was made in a factory close to where I live, from a store that I walked or biked to. 6. Buy a new one from a store that I had to drive to that was made in a factory hundreds of miles from where I live.

Ironically, #6, the least sustainable, would have the most positive impact on U.S. GDP.

The hammer choice also depends on context. If you need the hammer for a project that is an on again off again hobby, then you could probably wait to borrow one for your neighbor or find one at a garage sale. If you need the hammer for a project that has to be done by a certain time, you’ll probably go and buy one that is immediately available. If you need the hammer for a project that you are being paid to finish by a certain time and failure to do so results in a large financial penalty, then you definitely will get in you car and buy the one that is at the store, regardless of price.

Yes, I could go on and on. Sustainable consumerism would dictate that I buy the very best quality hammer I could find, perhaps made from recycled materials. It should also be produced in an environmentally sound way and by a company that pays a living wage to its employees.

As it stands, the burden is on the consumer to do the research and make the right choices and one could spend all their waking hours deciding instead of doing. I can only hope that someday, whether it comes about due to market pressures, public policy, regulation and/or just good faith, that sustainability will become “built in” and we won’t all have to work so hard for it.

@Tom — thanks for the cogent response. The problem I have with “sustainable consumerism” as a solution is that it puts the focus on the numerically least significant part of the equation, the individual consumer. Improved regulation of large-scale industrial and governmental activities has a much greater opportunity for quantitative payoff.