Settlement Reached in Fair Housing Case

Pam Kisch has a vivid, and unpleasant, memory of what happened when a federal civil-rights suit was filed against the owners and managers of a south Ann Arbor apartment complex this past March.

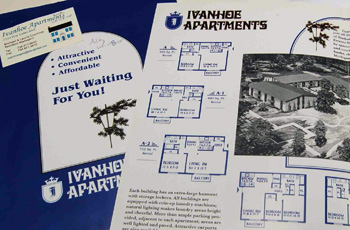

The Fair Housing Center of Southeastern Michigan found that potential renters of Ivanhoe Apartments in Ann Arbor sometimes had different experiences, depending on their race. (Photos by the writer.)

“Channel 7 came in and did a story that had these sound bytes from residents,” says Kisch, executive director of the Fair Housing Center of Southeast Michigan. ”People got on camera and said ‘No, there’s no discrimination here.’

“They might live there,” says Kisch, “but they don’t know.”

By then, Kisch was sure she did know.

Between 2006 and 2009, the Ann Arbor-based Fair Housing Center sent 18 men and women to the Ivanhoe Apartments to present themselves as prospective tenants. Some were African-American; some were white. The very different experiences they described prompted the U.S. Justice Department to file a race discrimination suit.

Although they deny any wrongdoing, the owners and operators of the apartment complex have now agreed to pay $82,500 to settle the case. The details of a settlement were announced this week by the Justice Department. The agreement must still be approved by U.S. District Court Judge Sean F. Cox.

The History of Fair Housing

The federal Fair Housing Act is a product of the 1960s.

Part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, it prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, sex – and, today, handicap or family status.

What it doesn’t do is provide a mechanism for ensuring compliance. That’s where groups like the Fair Housing Center come in.

Incorporated in 1991, the Fair Housing Center was organized by local NAACP chapters and others involved in civil rights issues. The idea, says Kisch, was to have an organization that actively protects the rights of those facing discrimination in housing.

The center provides community education, advice and advocacy for people who believe they’re victims of discrimination. It also provides legal referrals and – in some cases – investigative services.

Those investigations revolve around what the staffers in the Fair Housing Center’s small office in Kerrytown call “testing.” Testing establishes what one individual’s experience cannot. It provides a basis for comparing the way people are treated by rental or real estate agents, property managers or lenders.

In the case of the Ivanhoe apartments, “testers” who visited the complex within hours of one another reported being given different information about the availability of apartments, different access to the facilities and to materials like applications and brochures.

African-American testers reported being told there were no vacancies or that apartments would not be ready for move-in for extended periods of time.

White testers said they were told about more vacancies, shown more apartments, and more often shown facilities like laundry and storage areas. White testers were also given applications, business cards and other printed material more often than African-American testers.

“We’d heard about this place [Ivanhoe] practically since we opened,” says Kisch. “We finally decided to take a hard look at it and Kristen did a tremendous job.” Kristen Cuhran is coordinator of investigations at the Fair Housing Center.

Ivanhoe Apartments: What the “Testers” Found

Located on Pine Valley Boulevard, off Packard Avenue near the Georgetown Mall, the Ivanhoe Apartments are nestled in the midst of a several blocks of apartment buildings. The street winds beneath shady trees and, this time of year, the terraces that jut from each apartment are filled with flowering plants.

But the hospitable feeling projected from the street belies the evidence in the Fair Housing Center’s files.

For example: In a March 2006 test, two female testers met with apartment manager Laurie Courtney, who would eventually be a defendant in separate suits brought by the government and Fair Housing Center.

Both testers wanted to move into new apartments as quickly as possible. The white tester reported she was told one unit was available. She was given an application and told that, if she wanted to fill it out and return, the manager would be there all day.

The African-American tester arrived 90 minutes later.

Although the white tester had told Courtney she planned to look at other apartments, the African-American tester said she was told that the last available apartment had been rented and she should check back in the summer.

Several of the tests used a three-person strategy.

In one – on April 11, 2008 – the African-American tester reported she was told the earliest vacancy would be July or August. Her request to see an apartment was refused on the basis that the unit was occupied.

Two white testers – visiting separately – each said they were shown an apartment. The first white tester reported she was told one apartment would be available in about a week and that another unit would be open later in the month, on April 23.

The second white tester said she was told about a late April vacancy and another in mid-June. Courtney also volunteered to show the second tester’s husband the apartment over the coming weekend.

In another three-person test on Jan. 30, 2008, one African-American and two white testers visited Ivanhoe expressing interest in one- and two-bedroom apartments.

The African-American tester said she was told there were no apartments available and that there was a waiting list for some that could be open in a month – in late February. Courtney had told other testers that Ivanhoe did not keep waiting lists.

The two white testers reported they were told a one-bedroom unit was available and a two-bedroom would be ready in two to four weeks, by mid- or late February.

Other tests yielded similar results:

- On Feb. 8, 2008, an African-American tester was told that a one-bedroom apartment would be available at the end of the month. She was also advised that it was one of Ivanhoe’s smallest units. In contrast, a white tester was told a one-bedroom would be ready in 10 days and that it had a “view of the courtyard.” Both were shown the same unit. Courtney offered the white tester an application. The African-American tester had to ask for one.

- On Jan. 15, 2009, a white tester seeking a two-bedroom apartment was offered what Courtney described as the complex’s largest unit. An African-American tester was shown a different unit, which was undergoing repairs. As with many of the visits, the African-American tester’s visit was appreciably shorter than the white tester’s visit – 6 compared to 20 minutes.

- In one case, Courtney showed white testers three units while telling an African-American tester there was nothing available.

- Numerous testers reported that Courtney described the Ivanhoe tenant mix as a group with “no undergraduates,” an apparent bias against a class protected under a city of Ann Arbor ordinance. [Chapter 112 of the city code states (emphasis added): "It is the intent of the city that no person be denied to equal protection of the laws; nor shall any person be denied the enjoyment of his or her civil or political rights or be discriminated against because of actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, height, weight, condition of pregnancy, marital status, physical or mental limitation, source of income, family responsibilities, educational association, sexual orientation, gender identity or HIV status."]

Courtney remains at the apartments and says she expects to stay. “We’ve been here for 30 years,” she says, referring to her husband with whom she shares responsibilities as “resident managers.” She declined to discuss renting practices, referring questions to the owner.

The owner, Troy attorney David Lebenbom, operates The Ivanhoe Apartments under the corporate name Acme Investments Inc. He could not be reached for comment.

In the settlement agreement, the defendants deny “violating any law or engaging in any wrongful conduct of any type or nature as Plaintiffs allege in their actions.” The agreement further holds that the settlement ”is a compromise of disputed claims and is not an admission by Defendants, each of which expressly deny liability.”

The plaintiffs and defendants “have agreed that in order to avoid protracted and costly litigation, this controversy should be resolved without a trial.”

How the Testing Works

The blind testing employed by the Fair Housing Center, and organizations like it, has itself been tested. In a case that worked it way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1982, it was found to be legal.

From the files of the Fair Housing Center: These forms were used to record the experiences of testers sent to the Ivanhoe apartment complex on the same day. (Links to larger image)

Some testers are paid; some are volunteers. When they’re sent into the field, they don’t know the suspected bias being tested: it could be family status, for example, age or marital status.

They are, however, well prepared. Testers are ready to answer questions about where they and any spouse or partner work, how much they earn and their reasons for relocating.

In the Ivanhoe case, any inquiries were limited. But the testers’ individual dossiers are designed so that members of the protected group compare favorably to members of the control group. For instance, the African-American testers earned more and had longer tenure in their respective jobs than the white testers.

The Fair Housing Center investigates about 140 complaints a year, mostly from African-Americans, people with disabilities and people with children.

It’s helped file more than 60 fair-housing lawsuits with combined settlements of more than $1.4 million. A recent grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has allowed it to expand from Washtenaw, Lenawee, Monroe counties into Ingham, Jackson, and Livingston.

Landlords who stipulate that children can’t share a bedroom or that a ramp can’t be installed to accommodate a disability risk running afoul of the law. There are things that tip you off, says Kisch.

“You’re not likely to hear direct statements about race, but you’ll find that an apartment manager has lost an application, or that he or she is still waiting to get information from a previous landlord, or that there must be something wrong with a Social Security number so they’re not able to do a credit check. Eventually, they just wear an applicant down,” she says.

“It’s not illegal to act tough, but you’ll sometimes find a manager or landlord who’s got a lot rules and tells you you have to abide by them or your stay will be short. It’s OK, if they’re like that with everybody, but not if they’re selective.”

In the Ivanhoe case, the Fair Housing Center contacted the U.S. Justice Department with its findings. Justice staffers did some additional research and filed suit against Ivanhoe’s owner and manager. The Fair Housing Center filed a separate lawsuit. They were combined in federal court and settled together.

Because the settlement was reached before any of the discovery that precedes a trial, it’s not clear whether Courtney was acting on directions from the owner or on her own, says Judith Levy, assistant U.S. Attorney and chief of the civil rights unit for the Eastern District of Michigan.

But it doesn’t matter, says Levy. Owners are liable for an employee as well as any policy of their own.

Details of the Settlement

Under the terms of the agreement, Ivanhoe Apartments must put a nondiscrimination policy in place, post a fair housing sign on premises and include the fair housing logo and/or the words “Equal Housing Opportunity” in all published materials, along with specific language in rental contracts.

When any unit is available for rent, the landlord must post a visible “for rent” or “vacancy” sign in the apartment complex.

In addition, the company must provide training for all employees involved in renting or managing the apartments and keep records about the availability of apartments and prospective tenants’ inquires.

As part of the settlement, the defendants also agreed to periodic testing to identify any discrimination.

The U.S. Attorney’s office must approve the training and a number of other provisions. It’s also responsible for monitoring compliance, Levy says. The Fair Housing Center will also get periodic reports on compliance.

Three individuals discriminated against because of their race will share $35,000 in damages. The settlement also includes $7,500 in a civil penalty; and $40,000 to the Fair Housing Center as damages for its work testing and investigating the apartment complex.

The Fair Housing Center will pay its legal fees from that share and use the balance to further its work, Kisch says.

About the writer: Judy McGovern lives in Ann Arbor. She has worked as a journalist here, in Ohio, New York and several other states.

Great article. Once upon a time I worked at the county, helping to manage the database system used by area HUD-funded homeless service agencies, and hearing about the myriad hurdles that some folks have to go through to get an apartment was and is maddening and embarrassing for the community.

(Also, it would be good if I could spell my own last name.)

Good job Pam! My family has had some experiences with discrimination against families with children at another apartment complex in the area, and while our efforts to seek a remedy did not meet with success, the experience convinced me that various forms of discrimination are pervasive.

The federal judge, Sean Cox, assigned the case is the brother of Republican gubernatorial candidate Mike Cox.

Sean Cox previously presided over the federal criminal civil rights violation case of WCSD deputies indicted in connection with the death of Clifton Lee,Jr. and the assault of his brother Bruce Lee. Judge Cox drew controversy by placing much of the blame for Bruce Lee’s beating upon Lee himself for allegedly spitting upon a sergeant in charge at the scene.

Two deputies were eventually fired and others received disciplinary action ranging from suspension to demotion.

Thanks once again to the Fair Housing Center and to Pam and Kristen for all of efforts to enforce non-discrimination in housing!

My comment on the managing owner of the offending property magically disappeared somehow, but I urge everyone to google for his name and ponder why/how a major Obama supporter could allow this sort of repulsive racism to happen.