Column: Book Fare

Steven Gillis got lucky. Twice.

In the 1980s he was practicing labor law with a big firm in Washington, D.C., and writing in his spare time. The stock market was booming.

Steven Gillis, in his home office on Ann Arbor's east side. Gillis is founder of Dzanc Books as well as the nonprofit 826 Michigan, which are both based in Ann Arbor. His latest novel, "The Consequence of Skating," came out last week. (Photo by Mary Morgan)

“I started making some money and I got people to invest it for me – I’m smart enough to know I didn’t know how to invest it,” Gillis says.

“And I got lucky.”

As his writing started to take off, Gillis decided to practice law part time and devote more time to his fiction. A Detroit native and University of Michigan alum, he decided to move back to Michigan and settled in Ann Arbor. His first novel, “Walter Falls,” published by Brook Street Press in 2003, was well-received by critics and a finalist for a pair of literary awards. (Brook Street would publish his second novel, “The Weight of Nothing,” in 2005.) And he founded 826 Michigan, a nonprofit aimed at encouraging young people to develop their creative writing talents.

And then, in early 2005, he met up with Dan Wickett, who, like Gillis, was a regular at Shaman Drum Bookshop and at other local readings. And Gillis got lucky again.

Wickett was making a living as a quality control guy for the automotive industry while making a life with his family in Westland and writing book reviews for his literary website, Emerging Writers Network. As the site gathered what Wickett terms “a small following,” publishers started sending him books. (Which, Wickett notes, saved him a lot of money on books.)

“I’m a reader,” Wickett says. “And that’s what I was doing when I started doing the Emerging Writers Network – writing about writers I liked and why I liked them.” He also interviewed authors and publishers, and it was one of those interviews that caught Gillis’ attention.

“He sent me an e-mail,” Wickett says, “and said we should get together. We had dinner at Red Hawk before wandering over to Shaman Drum for a reading.”

Dan Wickett, executive director of Dzanc Books and founder of Emerging Writers Network. (Photo courtesy of Dan Wickett)

They hit it off. And what ultimately came from that meeting was Dzanc Books. (Pronounced Duh-ZAANCK, the name incorporates the first letter of each of their kids’ names. Gillis has two. Wickett has three.)

“As a writer myself,” Gillis says, “I knew there’re a lot of really good writers out there. And when I got lucky and made some money, and when I got lucky and my books started to publish, I wanted to do something for other writers.”

The financing for the nonprofit 501(c)3 came from Gillis. He prefers to keep the exact investment to himself, but acknowledges it was “a considerable sum.” And in just a few years, Dzanc has grown to take an important role in the literary publishing world.

Dzanc and its imprints – Black Lawrence Press, Other Voices, Keyhole and Starcherone – have published more than 40 books since 2007 and have another half-dozen on the way before the end of this year. Their lineup of titles is set through 2013. Periodicals under the Dzanc umbrella are Absinthe: New European Writing; Monkeybicycle, a print and online literary journal run by Dzanc’s art director, New Jerseyite Steven Seighman; and The Collagist, an online literary magazine edited by Ann Arborite Matt Bell.

“At Dzanc,” Gillis says, “if we find a book we like, how to market it never enters our head. We’ll figure out a way to get the readers we want. Other publishers have it backward: ‘This is really good, but how will we make money off it?’”

While interns are initial readers for most submissions, Wickett says that anything that Dzanc ends up publishing is read by both himself and Gillis. “If we both love it, then we’ll publish it,” he says. “If one of us can’t convince the other why it’s a great book, then it doesn’t make sense. If we can’t convince each other, we’re not going to convince anybody else in the world that it’s a good book.”

Bell, in addition to his duties at The Collagist and as editor of Dzanc’s Best of the Web anthology series, works with writers on the manuscripts Dzanc accepts for publication. Seighman does the covers for all the Dzanc publications (and he also set up Dzanc Books’ website – a marvel of clarity and organization).

“A Dzanc book has to be well-written,” Gillis says, “and brings a voice you haven’t heard before.”

More Than A Publishing House

But Dzanc has a parallel mission – community service – that distinguishes it in the publishing field.

“From day one,” Gillis says, “that was our plan: to be a publishing house that does a lot of good things.”

Says Wickett: “We both have that kind of attitude – that the more you can help others, the better. There’s that ideal of karma, and at least you feel a little better about what you’re doing on a daily basis.”

An example of that ethic is the annual Dzanc Prize, which gives $5,000 to an author who has a work in progress and a proposal for a year-long community service project – to pursue both.

“It was a good way to get a writer who was in the middle of a project to get some cash that might allow them to set some time aside, where the work they were doing would be this community-service kind of project that tends to spark some of the creative process as well,” Wickett says. “So instead of having to work 20 hours at Kinko’s or McDonald’s or something to earn that $5,000, they can be doing their project.”

Fittingly for a publishing house, the project should entail “some sort of literary community service,” he says. The prize is in its third year, and the projects have included a writing program for prison inmates in New England that produced an anthology of their work; a series of writing workshops for patients, their families and their caregivers at UM Hospitals’ Comprehensive Cancer Center; and a creative writing program operated in conjunction with English as a Second Language classes for Bhutan refugees in Pennsylvania. (Interested writers out there, note this: The deadline to apply for the 2011 prize is Nov. 1.)

There is also the Dzanc Writer in Residence Program, which places professional authors in public school classrooms for regular writing workshops. Locally, Thurston Elementary and Ann Arbor Open @ Mack are participating this school year.

College students get into the act, too. Dzanc’s internship program works with students from Eastern Michigan University and the Residential College at UM as well as Columbia College in Chicago, Illinois State University in Bloomington and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. And those are the formal relationships that offer credit hours. Students from other schools scattered around the country, Gillis says, contact Dzanc for a chance to do the work for love and experience.

There’s an international literary program in Portugal. And a program to encourage patronage of independent bookstores across the country. And a “write-a-thon” fundraiser. And an online mentorship program to link beginners looking for feedback on their writing with more seasoned scribes. All these projects are in various stages of execution.

How They Work: Swing Low, Sweet Overhead

Both Wickett and Gillis work at home. They don’t sleep much. They don’t waste time. Or money. And they hardly ever see each other. When Dzanc was on the drawing board, Wickett says Gillis told him, “‘what I don’t want to do is waste $1,000 a month on an office that you have to drive to.’”

“We’ve been officially partners since September 2006,” Wickett says, “and I would guess in that four years of time we have probably physically seen each other maybe 25 times. We’ve probably spoken on the phone five times.”

“It’s perfect for me,” says Gillis. “We have a great relationship. We see one another about once a month. … But by e-mail, we’re in touch 24/7. I don’t have to see his face; he doesn’t have to see mine.”

The mechanics of their working relationship reflect the new world of literary publishing.

“We know the whole medium is moving toward the Web,” Gillis says. “For readers and writers of literary fiction, most of us are online. Our world – we’re talking 5,000 to 10,000 people. If we sell 5,000 copies of a work of literary fiction, that’s a huge achievement. We can reach everybody we want to online and everybody that we want to reach is online.”

“We rarely meet our authors before their books are out – maybe at a convention,” Wickett says. “But a lot of the things we’re getting, we have no idea who the person is, we never met him – it’s all online.” (Dzanc’s first author, Roy Kesey, was living in Beijing when Dzanc published his novella “Nothing in the World.”)

“Authors are a solitary breed to begin with,” Gillis says. ” You don’t need to deal with the face-to-face. There’s no reason you can’t do that online, and that’s what we’re doing.”

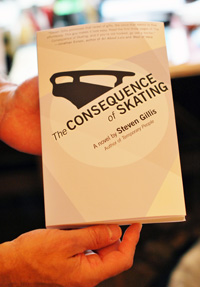

Gillis’ latest, “The Consequence of Skating,” came out last week under the Black Lawrence imprint. (Gillis’ “Temporary People” was published by the same imprint in 2008.) Also coming up are “How to Predict the Weather,” by Aaron Burch; “Unclean Jobs for Women and Girls,” by Alissa Nutting; and, from the Keyhole Press imprint, “How They Were Found,” a collection of stories by Collagist editor Bell.

Gillis, 53, has the official titles of founder and publisher at Dzanc, but he calls himself “the man behind the curtain.”

“Dan and I are the perfect pair,” he says. “I’m pretty crazy and Dan balances me out. I throw the ideas on the wall and Dan tries to make them stick.”

Wickett is 44, and oversees the day-to-day aspects of Dzanc’s publishing and community service operations as executive director and publisher. He studied statistics at UM: “I was decent in math and it seemed like something to do.” By the time Gillis offered him the opportunity to make a change, he says, he “had come close to being completely burned out on quality control in the automotive industry. As bad a time as it was to jump into asking for money in publishing, it certainly wasn’t a bad time to get out of the car industry.”

Says Gillis: “The only way you get stuff done is to jump – and then figure it out as you’re in midair. If you stand back and think, ‘How am I going to do this?’ – nothing ever gets done. I mean, I could still be practicing law in D.C.”

About the writer: Domenica Trevor is a voracious reader who lives in Ann Arbor and also has a home office, where she sometimes gets lucky, too.

It is so good to read about this enterprise, especially in a time that people are predicting the death of books. Publishing has always been a labor of love and rarely a wealth maker. Thanks for telling their story.

Great article–loved reading about Dzanc’s beginnings!

Thanks for writing this excellent article on Dzanc Books. I’ve

“known” Dan Wickett (in the internet sense of the word) for nearly seven years, but you still managed to flesh him out even more for me. He’s certainly one of the nicest guys, and most enthusiastic cheerleaders of literature I’ve ever met (on-line, at least).