SmartZone Group OKs SPARK Contract

Local Development Finance Authority board meeting (June 12, 2012): At its Tuesday morning meeting, the board of the LDFA took action on a number of significant items, including an approval of annual revisions to the LDFA’s contract with Ann Arbor SPARK to operate a business accelerator/incubator. SPARK is this region’s economic development agency.

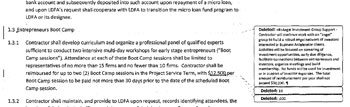

Extract from the marked-up version of revisions to the contract between Ann Arbor SPARK and the Local Development Finance Authority (LDFA).

Besides the usual housekeeping changes (like changing the year from 2012 to 2013), substantive revisions to the SPARK contract include the following: (1) eliminating support for angel investment groups; (2) adding licensed software to be provided by SPARK to incubator clients; and (3) adding a new talent-retention internship program.

Another significant deletion from the SPARK contract is $5,000 annually for maintenance of a web-based educational module for entrepreneurs, called Cantillon. According to an LDFA resolution from early this year, the LDFA had invested around $170,000 over the course of five years in the self-paced program, which integrates feedback from a mentor. The tool had been used by SPARK for its Entrepreneur Boot Camps and in other venues. However, a formal request for proposals to commercialize it – to license and market the software to a broader audience – did not result in a deal.

The initial RFP was issued last year, in August 2011, and elicited no responses. On re-issuance of the RFP, Kurt Riegger’s Business Engines was the only respondent. Riegger had been the developer of Cantillon. After negotiation, Riegger and the LDFA were not able to reach mutually agreeable terms. With the failure to reach an agreement, and the elimination of the item from the LDFA’s contract with SPARK, the Cantillon education module was characterized by city CFO Tom Crawford after the meeting as “on the shelf.” Cantillon will not be offered as a part of SPARK’s September 2012 Boot Camp.

In other business, the LDFA board approved SPARK’s marketing plan. A video that was presented to the board as part of that plan got a positive reaction from LDFA board member Stephen Rapundalo. He appreciated the fact that it focused on support for entrepreneurs, as opposed to enhancing SPARK’s efforts “across the board.” SPARK has a broader mission and other funding sources than just what’s expressed in its contract with the LDFA – but the contract is focused on supporting entrepreneurs in the development of new businesses. So Rapundalo wondered if it were possible for SPARK to put all of its LDFA-funded marketing budget towards that same entrepreneurial focus.

Skip Simms, SPARK’s vice president for entrepreneurial business development, told LDFA board members at their June 12 meeting that it’s possible he might be bringing them a proposal for a significant additional financial request. That request, Simms said, would be for an additional incubator that would provide Class A “wet lab” space. He said the amount he’d request would be consistent with the LDFA’s 15% fund balance reserve policy, and would only target the portion of the fund balance that exceeds the 15% level. For the recently approved FY 2013 LDFA budget, that works out to a maximum of around $157,000. Simms sits on the LDFA board as a non-voting ex officio member.

Reaction by LDFA board members to the wet lab incubator idea that Simms floated was extremely guarded. But they appeared to be open to being convinced – if they were to hear a clear business plan and case for the need for additional local wet lab resources for start-up companies.

It’s worth noting that the LDFA’s contract with SPARK is separate from the support that SPARK receives from the city of Ann Arbor, which has amounted to $75,000 annually for the last few years. The city’s $75,000 contract with SPARK for business support services is on next Monday’s June 18 city council agenda.

The full LDFA report begins with some brief background on the LDFA itself.

LDFA Background: Creature of the State

Ann Arbor’s local development finance authority is funded through a tax increment finance (TIF) district, as a “certified technology park” described under Act 281 of 1986. The Michigan Economic Development Corp. (MEDC) solicited proposals for that designation back in 2000. The Ann Arbor/Ypsilanti “technology park” is one of 11 across the state of Michigan, which are branded by the MEDC as “SmartZones.”

The geography of the LDFA’s TIF district – in which taxes are captured from another taxing jurisdiction – is the union of the TIF districts for the Ann Arbor and the Ypsilanti downtown development authorities (DDAs). It’s worth noting that the Ypsilanti portion of the LDFA’s TIF district does not generate any actual tax capture. The LDFA and the Ann Arbor DDA are similar – in having the same TIF capture funding mechanism, and having the same geographic area where taxes are captured. Yet the LDFA is different from the DDA in at least two significant ways.

That difference stems from the kind of taxes captured by the LDFA as opposed to the DDA. If a TIF-funded entity – like the LDFA or the DDA – did not exist, the taxes it captures would be collected anyway, and those monies would have some other “destiny.” In most cases, that destiny would be direct use by the municipal entity that levied the tax. By way of a concrete example, one of the kinds of taxes captured by the DDA is the city of Ann Arbor’s general operating millage. If the DDA did not exist, then a portion of city of Ann Arbor taxes currently captured by the DDA would go to the city’s general fund.

In the case of the LDFA, the story of an alternative destiny for its captured taxes has an extra wrinkle. That wrinkle is due to two things: (1) the kind of taxes the LDFA captures – Ann Arbor Public Schools (AAPS) operating millage; and (2) the way local schools are funded in Michigan. In Michigan, local schools levy a millage, but the proceeds are not used directly by local districts. Rather, proceeds are first forwarded to the state of Michigan’s School Aid Fund, for redistribution among school districts statewide. That redistribution is based on a per-pupil formula as determined on a specified “count day.”

If the LDFA did not exist, then the taxes captured by the LDFA would not be used directly by AAPS, but rather would flow into the statewide School Aid Fund. This is what underlies a standard explanation that local schools are not harmed by the existence of the LDFA. The idea is that the impact statewide is an inconsequential amount.

That’s why the TIF plan for the LDFA discusses the potential impact to local school funding as follows:

Based on current state law, this Plan shall have no direct impact upon the local school districts, as it has no direct impact upon the per pupil reimbursement from the State to the public schools. The impact to the State School Aid Fund will be approximately $24,000,000 over the 15 years of the LDFA plan. This translates to approximately $1,600,000 annually, or $0.79/student statewide.

So the LDFA board members are in one sense stewards of local tax dollars – because the money originates locally, and its amount is determined locally. But in another sense, board members are stewards of state funds – because the money would otherwise be distributed statewide.

Another way the LDFA is different from the DDA is that SmartZone status – given by the MEDC – is comparatively rare and limited in number. Only 11 such districts were created statewide. In contrast, the state statute enabling the formation of a downtown development authority (Act 197 of 1975) can be used statewide by any local entity that wishes to form a DDA in conformance with the statute. And that has resulted in the formation of over 130 DDAs across the state.

Ann Arbor SPARK Contract

Ann Arbor SPARK is a nonprofit focused on economic development. The LDFA hires SPARK to operate a business accelerator and perform activities related to it. The value of the contract for the 2013 fiscal year is about $1.5 million.

But SPARK has a broader mission than providing startup services to the LDFA. That’s reflected in its total operating budget in the range of $4.4 million (in 2011), of which the LDFA contract is a part. From SPARK’s mission statement:

Ann Arbor SPARK will advance the economy of the Ann Arbor Region by establishing the area as a desired place for business expansion and location … by identifying and meeting the needs of business at every stage, from those that are established to those working to successfully commercialize innovations.

Ann Arbor SPARK receives funding from area universities (most prominently the University of Michigan), local governmental units (including the city of Ann Arbor and Washtenaw County) and local businesses. The city of Ann Arbor’s support for SPARK has been at the level of $75,000 a year for the last few years.

At the June 12 meeting, LDFA board member Theresa Carroll reviewed a marked-up copy of the contract and scope of work that the contracts committee had produced. [.pdf scan of SPARK-LDFA marked-up contract]

Carroll described how the LDFA’s contracts committee and SPARK had exchanged comments on the new contract, which would be signed on July 1, 2012. She walked the rest of the board through the marked-up version of the document.

Carroll pointed to Article II 2.4, as having the intended effect of putting a control on a new internship program – by excluding that new program from a general but limited ability of SPARK to reallocate fees between categories. There is an addition under Article III 3.3 that Carroll described as not requiring more reporting by SPARK to the LDFA, but rather as clarifying what information is to be included in its already-required quarterly reports.

A significant deletion from the contract this year is removal of the $30,000 of support for angel investment groups. The previous contract had included support for a group “to build a robust angel network of investors interested in business accelerator clients.” No funds were to be spent for actual investment. Also struck from the agreement this year, Carroll continued, is $5,000 of support for the Cantillon web-based instruction module for entrepreneurs. That item was not discussed by the board in connection with the SPARK agreement – because Cantillon had a separate item on the agenda.

Added to the agreement is a section that covers a talent program, funded with $100,000, that is supposed to “create new programs that are designed to attract local talent, including and especially university graduates, and encourage them to stay and build a career in Ann Arbor.” The mechanism of the new program will be based in part on an internship program. And finally, Carroll said, there is a provision in the new contract for SPARK to be able to provide access to licensed software at the incubator. The amount specified in the agreement for that is $20,000.

Carroll characterized the changes as reflecting the budget, which the board had previously approved. Carroll described the next steps with the new contract as a vote by the board, to be followed by final review by the LDFA legal counsel, which is provided by Jerry Lax (a former Ann Arbor city attorney who’s now with the law firm Pear Sperling Eggan and Daniels). The MEDC will also be asked to review the agreement, she said.

Ann Arbor SPARK Contract: LDFA Board Deliberations

Stephen Rapundalo picked up on the new internship program. [The idea is that SPARK facilitates the hiring of interns by local companies – by funding the cost of the interns to the companies.] Rapundalo inquired what the allocation is for – does it go to SPARK’s administrative costs?

Skip Simms, SPARK’s vice president for entrepreneurial business development, responded to Rapundalo by distinguishing between the interns and the companies that hire them: “We’re paying the company, which we’re not really allowed to do in one sense of the language, but we’re actually contracting with the companies in this context.” The purpose of the internship piece of the initiative, Simms continued, is that when the company hires the intern, “the intern is our customer.”

SPARK is trying to introduce the interns to the startup, early-stage business community in Ann Arbor, and to introduce them to all the assets the city offers, Simms said. SPARK is trying to acquaint them with various aspects of working for a technology-based startup company. The idea is to encourage the students, as they enter the workforce, to put Ann Arbor on their list of places they want to live – along with New York or Chicago.

What SPARK offers, Simms continued, is a match to defray the cost of an intern to a company. The company pays $6,000 for a 12-week internship. SPARK then reimburses the company for half the cost of that internship. Simms described it as modeled on the Gani internship program at the University of Michigan.

It’s limited to one intern per company, Simms explained, so that SPARK is engaging as many companies as possible. The program is starting off with 10 interns. The program has launched and it’s going very well, Simms reported. If it’s successful, then SPARK wants to continue it through the end of the school year. Going back to Rapundalo’s question, Simms said that of the $100,000, around 15-20% would be for administration of the program.

Rapundalo worked through the arithmetic of $30,000 to pay the interns, another $15-20,000 for administration of it, for a total of around $45,000. To round out the LDFA’s $100,000, Simms said there are some other talent-related programs they’re “kicking around,” including the possibility that the internship program would be extended.

When it emerged in conversation with other board members that the first 10 interns had easily been placed and that there was a lot of demand, Rapundalo wanted to know why SPARK didn’t just expand the pool of current interns. The answer from SPARK’s business accelerator director – Bill Mayer, who was seated in the audience – was essentially that 10 was a number that was “containable” for now. Ned Staebler wanted to know what the program’s relationship is to the Intern in Michigan program.

Mayer told Staebler that SPARK is undertaking its internship program independently of the Intern in Michigan program. Half of the program is allowing startup companies to afford an intern, but the other half is to stress the “quality of place.” Whether it’s a scavenger hunt or attending Top of the Park, SPARK has the interns visiting landmark Ann Arbor locations in partnership with other organizations like the Ann Arbor Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Staebler noted that Intern in Michigan can do that sort of thing, if you tell them: We need X number of interns that fit Y criteria. The Intern in Michigan program has thousands of resumes at this point, Staebler said. Mayer allowed that there could be an opportunity to look at it, but SPARK is handling the initial group “hands on” to ensure that the pilot goes well.

Rapundalo ventured that, based on his own experience, you end up doing a lot of things you didn’t plan on doing – like vetting, and other things that take a lot of time. The Intern in Michigan program is good for managing a large pool and perhaps narrowing it down to a smaller set, but would not necessarily be able to provide exactly the right person. And that’s what a company wants, Rapundalo said – for exactly the right person to just walk through the door and start doing something useful.

Mayer pointed out that the interns are still in college, and the goal is to reach them at that point, so that they can be retained here. Simms pointed out that SPARK is also inviting other companies who have interns, besides those subsidized by SPARK, to participate in social activities.

LDFA board treasurer Eric Jacobson wanted to know if the interns that SPARK is subsidizing are Ann Arbor natives. Simms explained that SPARK doesn’t care that much about where students come from, as long as they’re getting exposure to the career opportunities. So picking up on Simms’ earlier explanation that the interns were SPARK’s “customer,” not the company, Staebler wondered if SPARK wasn’t having it both ways: The intern is the customer, but the company has to be in the LDFA district.

Simms said that the company has to be in the district, because that’s where SPARK wants the interns showing up to work every day. Didn’t that mean that the company was SPARK’s customer? Staebler asked. Simms allowed that the company is a “beneficiary, for sure.” Staebler said he wasn’t against the program – he just felt it was actually the company who’s the customer: “I’m all for getting more smart people here!” he said.

Outcome: The board unanimously approved the contract with SPARK, subject to review by legal counsel.

SPARK Marketing Plan

Because Donna Doleman – Ann Arbor SPARK’s vice president of marketing, communications and talent – could not attend the LDFA board meeting, the marketing plan was reviewed by SPARK’s marketing coordinator, Andria Signore. Highlights of that plan include the SPARK website, various event sponsorships, a Google AdWords campaign, hosting SPARK’s own events, media relations, and tours. Goals of the marketing program include maintaining the pipeline of business accelerator clients and entrepreneur boot camp applicants, getting 2-3 online media mentions per month, and maintaining the SPARK Central incubator at 80% occupancy. [.pdf scan of SPARK marketing plan]

Signore presented the LDFA with two recently produced videos, one focusing on SPARK’s entrepreneurial services, and the other focusing on Ann Arbor as a sense of place, which is part of the Pure Michigan campaign. [Ann Arbor SPARK: Entrepreneurial Services] [Pure Michigan Business Attraction]

The first video includes SPARK CEO Paul Krutko posing the question: “Who’s the next Apple? Who’s the next Microsoft?” and then compares SPARK’s entrepreneurial services to “economic gardening,” focusing on the unique attributes of the Ann Arbor region that will identify the next new disruptive technology that will change the world. It features a quote from Steve Jobs: “Let’s make a dent in the universe.”

The Pure Michigan video also uses gardening imagery, as Menlo Innovations CEO Rich Sheridan compares the idea of Terroir – the characteristics of land that give food that’s grown there a unique character – to the kind of companies that emerge in the Ann Arbor area. The swelling music and heartfelt voiceovers (“Pure Michigan says, Welcome Home”) led to a quip at the LDFA board table: “Does anybody else need a tissue?”

Signore explained that the Pure Michigan video is part of a national campaign – to local and national bloggers and media. The entrepreneurial services video is being hosted on the SPARK website and all of SPARK’s social media channels, she said. They’re trying to reach out to all the local news outlets and will use it in presentations that SPARK gives, she said.

Stephen Rapundalo noted that in the past, the LDFA budget allocation for marketing was to some extent arguably something that enhanced SPARK’s efforts across-the-board. What SPARK had done with the first video was to put more emphasis on entrepreneurs, which he said “is a great thing.” It’s where he’s always wanted those dollars to go.

But some marketing dollars still go to the “bigger picture,” he noted. What’s stopping SPARK from focusing the entire marketing budget from the LDFA on the entrepreneurial aspect? Rapundalo wondered. He stressed that he was a proponent of the idea that everything the LDFA paid for should relate directly to the services that SPARK provides under its contract – the entrepreneurial services, period.

SPARK’s Skip Simms replied by saying that as an organization, SPARK serves existing big companies as well as entrepreneurial enterprises – because SPARK serves all of the growth companies, the “driving industries,” he said, from Toyoto to Terumo. The entrepreneurial component of the marketing effort, he continued, is more than half of overall marketing and he didn’t see SPARK letting up.

SPARK has increased somewhat its activity in the area of attracting businesses to Ann Arbor, Simms said. When the LDFA started helping to fund the marketing efforts of SPARK, he said, the part that was aimed only at the city of Ann Arbor was around 33% of the marketing budget. In the current agreement, he said, that’s been cut to 30% – because they were trying to be reasonable and fair.

Paula Sorrell, an ex-officio LDFA board member who works for the MEDC, ventured that a marketing budget has a mix of the specific technical part and brand development [which Rapundalo had described as SPARK's "big picture" efforts]. Ultimately, the success of the marketing effort, she said, is: “Did it put butts in seats? Did it get people through the door?” She felt that the way to approach it was to look at the actual results – how many new companies were started or located here – and not to ask if the mix of branding and specific message was right. It should all be tied back to metrics, she said.

Rapundalo said he agreed with Sorrell, but still looked at it from the point of view that the program gets funded by the LDFA. He drew a distinction between that LDFA funding for marketing, and the separate allocation given by the city of Ann Arbor [$75,000 annually]. The Ann Arbor city contribution, he continued, was generally understood to go to support the brand and the broader activity of SPARK. He took the perspective that the LDFA-funded marketing should be related back to the specific activities of the LDFA. He wanted to see the use of LDFA money used on the “branding out of the entrepreneurial services.”

Sorrell said she didn’t disagree with Rapundalo, but said, “If you’re going to police it, police it on the results.” Dick Beedon ventured that the results were metrics, so he wondered what the specific metrics were. Simms told Beedon that the metrics are in the reports that SPARK submits to the LDFA quarterly – data like how many entrepreneurs SPARK served, how many startup companies SPARK served, and the like. How that’s tied back to a click-through from a Google ad or if it resulted from someone who stumbled across their video – Simms did not know.

Rapundalo came back to the fact that the one video focuses solely on entrepreneurial services, and it ties directly back to what the LDFA does. That’s very visible and very tangible. The fact that we have the video and we didn’t have the video before was, to Rapundalo, an “outcome.” He’d like to see more of that. He said he could easily justify to anybody who asked: Where is this money going?

Beedon indicated that some of the metrics included in the presentation were things like 6,000 Facebook “likes.” He felt that metrics are important and the metrics are related to the audience. A CEO who could move his company, Beedon said, is one audience. But employees who might potentially stay in the area are another audience, he said. It’s difficult to allocate marketing resources to different audiences, Beedon said.

Ned Staebler picked up on the idea of audience, and noted that Signore had presented a list of 20 different targeted audiences. How can you craft targeted messages to each of those audiences? he asked. So Staebler asked which of the audiences were the top priority and what messages are being sent to those? Signore told Staebler that the priorities are the entrepreneurs, decision-makers, talent and investors. “Decision-makers where?” asked Staebler. “My wife is a decision-maker.” Signore indicate that it’s “decision-makers in the sense of someone who can move their company to the Ann Arbor area or not.”

Simms added that a lot of what SPARK does by way of marketing doesn’t cost cash – but rather time and resources. SPARK doesn’t spend a lot of money on ads per se, he said, because they try to maximize what they can get done for free.

Outcome: The board unanimously approved SPARK’s marketing plan.

City of Ann Arbor Administrative Services Agreement

The LDFA board considered the new administrative services agreement with the city of Ann Arbor. It included a municipal service charge of roughly $13,125 and a charge for direct services from city of Ann Arbor financial specialist Ken Bogan for around $15,225 – for total of $28,350.

City of Ann Arbor CFO Tom Crawford gave a brief description of that agreement. [.pdf scan of city of Ann Arbor-LDFA administrative services agreement]

Outcome: The board gave unanimous approval to the administrative services agreement with the city of Ann Arbor.

Cantillon Education for Entrepreneurs

The board was briefed on the ultimate inability to commercialize Cantillon.

Cantillon: Background

By way of background, Cantillon is a self-paced web-hosted educational program (courseware) that entrepreneurs can use in concert with a mentor, who can also log on to the program to review and provide feedback on work that the entrepreneur has done. Cantillon is hosted on the University of Michigan MEonline platform. Cantillon includes video presentations from local business leaders like Tom Kinnear and Roger Newton, among many others.

Cantillon was developed incrementally, adding different sections, over the last five or more years. The course takes the user through the process of developing specific elements for building a business: executive summary, financial plan, marketing plan, product roadmap, and business model. For some LDFA board members, the Cantillon program was seen as a way of creating a tangible asset from an activity that the LDFA wanted to fund anyway – the education of entrepreneurs.

In a telephone interview with The Chronicle, Kurt Riegger – who was paid to develop Cantillon for the LDFA – described the courseware as relying crucially on a mentor, and he stressed the fact that it’s not an academic exercise. That is, the Cantillon course is meant to help entrepreneurs develop, say, an actual financial plan for an actual business they are trying to start. It’s also a cost-effective way to train entrepreneurs, he said, because they are to some extent using the tool to educate themselves, and they can make the most efficient use of a mentor’s time.

In the past, Cantillon has been offered as a supplemental tool for participants in SPARK’s Entrepreneur Boot Camp, a two-day course offered by SPARK each year (full-price tuition is $1,500 per “camper”). Part of SPARK’s pitch to potential Boot Camp participants is to “hone your sprawling corporate narrative into a lean, mean call for venture capital.”

Cantillon has received positive reviews from Boot Camp participants, according to SPARK’s April-June 2009 quarterly report to the LDFA:

A satisfaction survey of the Entrepreneurs Boot Camp participants was conducted immediately after camp. One question focused on the value of the Cantillon Executive Summary unit and its impact. For the Camps in 2007 – April 2009, the Cantillon average score was 5.90 on a scale of 1 to 7 where 7 is Excellent and the impact of the Executive Summary averaged 5.71. From a survey of mentors who have engaged with Entrepreneurs to use the course at Camp, they had a similar high rating and opinion.

Cantillon is configured so that it’s possible to monitor how much time a user is spending on various sections. SPARK’s October-December 2008 quarterly report includes some examples of the more detailed analysis of user activity. The set of users is described in the report as “mostly attendees of the November Boot Camp and focused on Unit 2 ‘The Executive Summary.’”

Last Login: December 22,2007, 2:32 PM

Total Login Time: 14 hours, 0 minutes

Excellent activity – 24 plan reviews taken

Last Login: October 14, 2008, 9:00 PM

Total Login Time: 4 minutes

Limited activity – downloads

In August of 2011, the LDFA issued a request for proposals (RFP) soliciting offers to commercialize Cantillon. [.pdf of August 2011 Cantillon RFP] There were no respondents by the time the RFP deadline. However, after the RFP had closed in October, Riegger made a proposal.

The LDFA board draft minutes for its Jan. 24, 2012 meeting show that at least some board members were not favorably inclined towards Riegger’s proposal. Part of the objection stemmed from the fact that Riegger had been paid to develop Cantillon and that he had not responded to the first RFP.

Cantillon (moved up on agenda from Other Business): [Phil] Tepley asked the record reflect his objection to selling Cantillon back to the developer at 10 cents on the dollar. [Mark] Maynard noted that the proposal by Kurt Riegger was made after the RFP closed. [Dick] Beedon agrees on the record, with Tepley, that the LDFA should not be involved in software development. After discussion, the Board requested that the Cantillon Committee draft a resolution, to be considered at the next meeting, based on the Committee’s recommendation to sell Cantillon to Kurt Riegger.

The sentiment that a formal RFP process should be followed resulted in a re-issuance of the Cantillon RFP (twice, on March 16 and April 10). The subsequent re-issuances of the RFP were identical to the original issuance, with the exception of a set of requirements that included a dollar amount:

1. Proposing party will bear all responsibility and costs for content maintenance and end-user support.

2. The LDFA will retain the right to market and provide Cantillon to entrepreneurs in the LDFA region at no cost to the LDFA.

3. Proposing party will pay to the LDFA fair market value of not less than a reasonable royalty or lump sum payment of not less than $25,000.

The June 12 resolution that the board passed on Cantillon pegged the LDFA’s investment in Cantillon over the last five years at around $170,000. The resolution also pegged the actual usage of Cantillon as low, and attributed most of the usage to University of Michigan students:

Whereas, while over 500 entrepreneurs, including 250-300 boot camp attendees, have registered to use Cantillon, activity reports provided to the Cantillon Committee by the provider did not show evidence that more than a small percentage made substantive use of it;

Whereas, it was apparent that the subset of users that received the most value were University of Michigan students who used Cantillon as part of a business and finance class and through a venture capital club;

Whereas, while these University of Michigan students technically fall within the TIF district and are therefore eligible users, it is the opinion of the Cantillon Committee that it is not the intention of the LDFA to fund programs utilized primarily by university students;

In a phone interview with The Chronicle, Riegger objected to the way the resolution discounts UM students as users of Cantillon – because it seemed to him inconsistent with MEDC’s rationale for choosing Ann Arbor as a SmartZone location. It’s the presence of the University of Michigan that made Ann Arbor a logical place to enable an LDFA here – as opposed to Bad Axe, or some other Michigan city, he said.

Riegger also questioned the merits of the conclusion that only a small percentage of Boot Camp participants made substantive use of Cantillon. It’s possible to assess Cantillon’s use in terms of the relative strength of the teams who participate in Boot Camp, he contends. [The Chronicle confirmed with SPARK that an evaluation is done of Boot Camp participants to assess their performance – and a Best of Boot Camp designation is given to one of the teams.] Riegger contends that if you divide Boot Camp participants into thirds, based on the strength of the teams who participate, then it’s the top third that actually get the most benefit from Cantillon. That is, the strongest entrepreneurs are those who are able to “roll up their sleeves” and get benefit out of Cantillon’s instruction.

In any event, Riegger was the only respondent to the RFP, and negotiations commenced between Riegger and the LDFA.

Based on an email chain between Riegger and LDFA board member Theresa Carroll, negotiations appear to have foundered on the amount of the royalty and whether the $25,000 would take the form of cash or in value provided through support. An email from Riegger on May 2, 2012:

Hi Theresa,

The answer to a cash upfront payment is no. To a commitment to provide support valued at $25K over 2.5 years, the answer is yes.Did you or the committee have some comparables that suggest a 20% royalty is market pricing and a 5% is not?

Cantillon: Board Discussion

At the June 12 LDFA board meeting, Theresa Carroll reported to the board that the committee had negotiated with the one respondent to the RFP – Kurt Riegger. They’d gone back and forth, and “just couldn’t get there on terms,” she said. That had been a month or so ago, she reported [early May 2012]. She said she’d just received an email the previous day with a message from Riegger, but had not had a chance to assess it. Not all board members had seen the email, so a portion was read aloud. The compete text sent from Riegger:

Hi Theresa,

I wanted to toss out another idea that might solve our mutual problems. If a department within the University of Michigan were willing to pay a $1 to have the rights to Cantillon, would you be able to license the content to them? They would continue to offer it for free to the LDFA region.

Board members seemed generally receptive to the idea of licensing the content to UM, or some educational entity. But there was some question about what the appropriate process would be to do that, if indeed UM wanted to do that. The idea of issuing yet another RFP was not met with enthusiasm by the board.

City CFO Tom Crawford, who sits on the LDFA board as an ex officio non-voting member, said he’d just seen the email. But his initial impression is that the university really should respond through an RFP process. Crawford pointed out that the university was certainly aware that the previous RFP was out there.

Dick Beedon felt that if nothing went forward, it would not be a big loss. Crawford offered the view that the LDFA had established the value of Cantillon [in terms of the cash someone is willing to pay] as essentially nothing, which Beedon agreed with. Crawford said the LDFA board could bat around ideas all day, but he would not advise spending a lot of additional time on it.

Carroll asked if it made sense for her to speak with Riegger about the email. The board’s response was essentially that the ball is in the university’s court, if it were interested in pursuing it. The board felt that whoever Riegger might have talked to at UM – and Riegger seemed to indicate from the audience at the meeting that he’s talked to someone – could contact either Carroll or Beedon.

In any case, according to Jennifer Cornell, public relations consultant for SPARK, Cantillon will not be offered to Entrepreneur Boot Camp participants this fall.

Outcome: This was a point of information and did not result in a vote.

Wet Lab Space?

In an item added to the agenda at the meeting, Skip Simms alerted the board to the possibility of a possible “significant ask” of the LDFA in the future. Simms is SPARK’s vice president for entrepreneurial business development and sits on the LDFA board as an ex officio, non-voting member.

He noted that SPARK has been running an incubator in downtown Ann Arbor for several years that is fairly traditional – with office space. There could be an opportunity for an incubator that offers space to startup companies that need “wet lab” space. It would be primarily for life science companies, Simms said, or perhaps for alternative energy companies. Class A wet lab space for incubation companies in the city of Ann Arbor doesn’t really exist, Simms said. He thinks there may be a need, as well as an opportunity for SPARK to provide that Class A wet lab space.

As with any incubator, Simms continued, it would need to be subsidized. Simms said SPARK was in very early discussions with some parties – in the city, but not in the LDFA district – to create such an incubator, if the need did arise. He felt that the timeframe would be within the next year – so not imminent, but still relatively soon.

Simms said that SPARK would come back to the LDFA for a formal request to amend the contract for a new program, modeled on the contract SPARK has with the LDFA for the current business incubator. For example, SPARK would charge rent, and would manage the facility and provide business accelerator assistance for any of the tenants.

Simms indicated that the amount of financial support that SPARK would need could require the LDFA to approve tapping its reserves. Currently there’s a policy of maintaining reserves at 15% of revenues. He said that the request for support for the wet lab space would not require dropping below that. [For the recently approved fiscal year 2013 LDFA budget, the fund balance reflects a 25% reserve, and the difference of 10 points works out to a maximum of around $157,000 for the request.]

Simms said he did not know what the dollar figure would be of SPARK’s request to the LDFA, but that it would “not be insignificant.” Simms stated that SPARK believes the wet lab incubator fits clearly within the LDFA mission. He wanted to get a feel for the board’s reaction to the idea.

Board chair Dick Beedon asked if SPARK had done any research on the need for such a facility. Simms replied that it’s not an ongoing process. SPARK learns about a need by the number of entrepreneurs who contact the organization, Simms said. The need comes from research institutions – as life science companies are spun out of an existing research institution. Primarily that’s the University of Michigan, he said. So SPARK is in constant communication with University of Michigan Tech Transfer, which has its own incubator. [LDFA board member Mark Maynard is marketing manager for UM Tech Transfer, but he was not able to attend the June 12 meeting.]

UM Tech Transfer is restricted in hosting only companies that are using university-licensed technology, Simms said. The question, he added, is where those companies go after Tech Transfer’s incubator. That’s were the need is for Class A space, he said, as opposed to somebody’s kitchen.

Simms also described some companies started by people who left Pfizer who need wet lab space – working on drug development, for example. Simms felt there was a consistent flow of consistent demand – large enough to pay attention to. The state of Michigan chose life sciences as one area of focus back in 2000, Simms said, and he felt it’d be a shame to give up on it at this point.

Stephen Rapundalo said he’d like to see some kind of quantification of the demand. He raised the issue of rates you can charge tenants in a Class A wet lab incubator. Simms indicated that would be laid out for the LDFA in any plan that were brought forward.

Rapundalo wondered if the wet lab incubator would be scalable: Say you build a six-company-sized incubator, and it turns out there’s demand for another six. That would be a factor in discussions with the potential developer and landlord, Simms answered.

Phil Tepley wanted to know how it would affect the community – because it could be seen as a subsidy for PhDs who want to join up with venture capitalists. Responding to Simms’ statement that we shouldn’t give up on the life sciences, Tepley quipped, “Cover your ears, Steve [Rapundalo], but maybe we should [give up on life sciences.]” [Tepley was referring to the fact that Rapundalo is CEO of MichBio, a trade association of life sciences companies.]

Tepley also wanted to know what the return-on-investment is for such incubators around the state: How does that translate into jobs in the community?

Tom Crawford, the city’s CFO, wanted to know what companies do now if they need that kind of wet lab space. Simms indicated that SPARK currently operates a wet lab incubator in Plymouth, so people are referred there. There’s also one on the south side of town, outside the city – SPARK refers people there, too.

The question was raised about what exactly Class A space includes. Rapundalo indicated that the old Pfizer labs are Class A. Simms described hoods, air-handling, tanks, hoses and connections, waste control and positive pressure. Tepley wanted to know what kind of businesses need Class A facilities. Rapundalo ventured that drug companies would be one example, or companies in the cell-culture business. Other companies needing such space would include those making research products and devices.

Ned Staebler asked about the availability of other wet lab space – whether it’s private or public. He wanted to include the wet lab assets of a broader region in the assessment, not just in the city of Ann Arbor. Managing such a facility can turn into a “pain in the butt,” he said, or can also become a “real estate play,” which is a distraction to providing business accelerator services. He’d want to be convinced there’s a need before going into that kind of wet lab incubator business, Staebler concluded.

Beedon ventured it would be fair to say the board would be open to discussion of Simms’ idea, assuming it had an appropriate business plan to support it. Rapundalo agreed with Staebler. Rapundalo felt that no one had done an asset assessment of Class A space – what’s available and what the demand is.

On the cost issue, Tepley stated that if the LDFA has a rule of maintaining at least a 15% fund reserve, then he did not want to maintain anything above that. He wanted anything above that 15% put to use. He did not know if a wet lab incubator was the right use. But if Simms could present a case that gives a positive return on investment, that’s better than letting it sitting in the bank, Tepley concluded.

Outcome: This was not a voting item for the LDFA board.

Present: Eric Jacobson, Christopher Taylor (Ann Arbor city council), Paula Sorrell (MEDC, ex officio), Theresa Carroll, Tom Crawford (city of Ann Arbor CFO, ex officio), Richard Beedon, Skip Simms (representative of Ann Arbor SPARK business accelerator, ex officio), Stephen Rapundalo, Ned Staebler, Phil Tepley.

Absent: Mark Maynard, Vince Chmielewski.

Next meeting: July 24, 2012 from 8:15-10:15 a.m. in the second-floor city council chambers at city hall, 301 E. Huron St.

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public bodies like the local development finance authority. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

Dave,

The idea that taking money from public education doesn’t harm the schools because reduces the amount of money available for the School Aid Fund, rather than coming dollar-for-dollar from the AAPS, strikes me as a tad cynical, and perhaps short-sited as well.

Another way of phrasing the rationale for funding SPARK with School Aid Fund revenues is, “As long as SARK is funded at the expense of other kids, and not our kids, it’s OK to use public education funds to fund it”. In Michigan, voters voted to fund k-12 education primarily from centralized funds. This was done to help reduce the effect of the accident of their parent’s circumstances on children’s education. One side effect of this model of funding education is to remove the obviousness of the connection between taxes paid, and school funding: “Based on current state law, this Plan shall have no direct impact upon the local school districts, as it has no direct impact upon the per pupil reimbursement from the State to the public schools.” So what happens if every one else treats the School Aid Fund as a personal slush fund? Besides reducing public education resources, this undermines the credibility of public institutions by playing those who play by the rules as suckers.

SPARK’s activities may be the most worthy activities in which government can engage, but why are we funding it with taxes “reserved” for public education? I thought an educated work force was critical for “21st century jobs”. If we can raid the School Aid Fund for non-school activities, what’s the point of having a “segregated” or “restricted” fund in the first place?

“The idea is that the impact statewide is an inconsequential amount.” This argument is akin to the idea that shoplifting a pack of gum is OK because it is “an inconsequential amount”. Try using it on a convenience store owner.

“…board members are stewards of state funds – because the money would otherwise be distributed statewide.” Actually, board members are stewards of state education dollars. Are we sure that the SPARK board members are better stewards of education funds than the schools themselves? If true, why not give SPARK all state education funds?

One way of looking at SPARK’s diversion of education taxes is that it happens simply because there is no organized constituency to oppose it – they do it because they can get away with it. The rationalizations could just be the attempts of mostly-good people to justify what they know is wrong, but cannot stop themselves from doing anyway.

Am I am missing something? Wouldn’t be the first time.

John,

I don’t think you’re missing anything on the conceptual level – related to what the impact is statewide of the LDFA’s TIF or the various arguments against taking the TIF-capture approach.

But in more than one place I think your comment blurs the difference between (1) SPARK as the contractor (which engages in a whole bunch of other non-LDFA funded activities as an independent non-profit) and (2) the LDFA as the TIF-funded entity that contracts wih SPARK to perform a specific set of tasks. I don’t mean to be picking a nit, here. It’s an important distinction for evaluating whether school systems, or indeed taxpayers in general, across the state are getting an actual benefit from the formation of the SmartZones.

So, whenever Ann Arbor SPARK is asked to describe its own positive impact, there’s different categories of statistics to which SPARK can appeal, among them: companies retained in the Ann Arbor region; companies attracted to the Ann Arbor region; jobs retained in the Ann Arbor region; jobs attracted to the Ann Arbor region. But the items on that list are not what the LDFA pays SPARK to achieve. Rather, the LDFA contracts with SPARK to do the things that will create new companies and to create new jobs. Those are the stats that are important for evaluating this TIF-capture approach to funding.

And if you review the part of the LDFA meeting report on SPARK’s marketing plan, this is exactly the same issue that Stephen Rapundalo was raising at the meeting. Rapundalo wanted to see SPARK using the LDFA’s money to market specifically the entrepreneurial services that SPARK provides – not the general “big picture” branding activity. That’s because it’s the entrepreneurial end of things that the LDFA is paying SPARK to address.

When you write, “SPARK’s diversion of education taxes” [instead of "the diversion of education taxes through LDFA's TIF"] it leads us, I think, to lump all of SPARK’s activities into one big gob and not differentiate between LDFA-funded activities and outcomes, compared to SPARK’s other activities and outcomes. Those other SPARK activities are funded, for example, directly by the city of Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan and other municipalities and businesses. Blurring these activities and results causes the glow of SPARK’s potentially positive impacts to be reflected back on the LDFA. But who cares if the LDFA gets a little extra glow?

Well, Ann Arbor’s LDFA TIF capture was established for a 15-year period in 2003. So at some point between now and 2018, when the LDFA charter expires, I imagine someone will get the idea to extend or renew it. If and when that conversation takes place, I think it’ll be important to make sure that we don’t inadvertently put everything SPARK does into the win column for the LDFA.

When the SmartZone was established by a vote of the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners, [link] it was said to have a very specific mission. “The purpose of the SmartZone is to support small, start-up technology companies, primarily in the information technology field within the Zone.” It appears to me that the LDFA has gone far beyond this mission into being a general business development and business subsidy group.

I recall that there was some fuss a few years ago about SMART spending LDFA funds outside the zone in which spending was authorized. I don’t recall the details, but from what I’m reading here, there seems to be some drift again. Certainly funding wet labs (which tend to be biology/chemistry) in the old Pfizer complex on Plymouth Road does not seem to be a use that conforms with IT development in the downtown.