In it for the Money: Not Safe for Work

Editor’s note: Nelson’s “In it for the Money” opinion column appears regularly in The Chronicle, roughly around the third Wednesday of the month. FYI, Nelson has recently written a piece for The Magazine about a device to adapt a digital camera to pinhole technology, called Light Motif – possibly of interest to Chronicle readers.

This was going to be another column about “gun control.” Despite my repeated threats to be “done talking about guns,” it turns out I had another roughly 8,000 words worth of opinion, math, and legalistic nitpickery. (Spoiler alert: Prospects are bleak for “gun control” fixing the problems we want fixed.)

But then events unfolded in Boston, and it was the opinion of this fine publication’s editor that maybe we should go with something a bit more “light and fluffy” to break up our unbearably bleak march to the grave.

To this I assented [1]. It’ll be back to guns next month.

So for this month I’ll return to a topic I’ve written about before: education. This time I’ll start by asking: How do school books get written? And who writes them?

I can shed some light on the first question, because the answer to the second one is: This guy! And not all of them are classroom reference works on Internet pornography.

The Writer’s Life

Folks often wonder how it is that I make a living writing, knowing as they do that my pay for this monthly column basically just about covers a half-week of childcare for my baby (i.e., the time it takes to write the column itself, with a little left over for rice and beans.)

Constant Readers are already aware that I write lots of other stuff, too (from offensive robot sexploitation novellas to offensive giant-squidsploitation short stories and largely inoffensive geeky craft books). While this sort of stuff does earn me much cred among the sorts of folks who have strong opinions about which Star Trek Enterprise captain is the best kisser [2], it doesn’t begin to pay the bills.

My total residuals off those projects for the last month or two would maybe buy a cup of coffee, provided it wasn’t the sort that required milk be steamed.

So what pays my bills? Commercial work.

For the last five years or so that has largely meant editing textbookish classroom references. “Editing” is a pretty broad term. To the uninitiated it tends to mean “checking for typos and whatever” (not really; that’s more “proofreading,” which is done by a “proofreader”). Or you might thing it means “making sure all the formatting is consistent and whatever” (nope; that’s “copyediting,” and it’s done by a “copy editor”).

In publishing, “editing” is a continuum. On one end are the folks you probably think of when you imagine a publishing house: These are “developmental editors,” and they function a lot like project managers, working with authors, artists, and designers to shepherd a book project from “pretty bad idea” to “something in the remainder bin that you idly page through while waiting for your kid to come back from the bathroom.”

At the other end of the continuum are freelancers like me, basically writing books via collage. I gather together a bunch of existing articles and excerpts, and paste ‘em all together with intros and prefaces and timelines and classroom exercise and discussion questions and other pedagogical crutches that I write.

I only bring this up because I know Chronicle readers care about education, and this particular gig sheds some decent light how the stuff in our kids’ schoolbooks get there.

How the Textbooks Get Made

Illustrative example: I recently put together a classroom reference on Internet pornography (not kidding). The book consists of a couple dozen point-counterpoint pairs on topics like “Access to online porn does/doesn’t encourage rape” or “Teen/preteen sexting should/shouldn’t be prosecuted as child pornography” – fun stuff like that.

I hunt down these articles, then revise and massage them so that they’re high-school accessible, because that’s the market for this book – high school libraries. That’s my job:

I write reference works on pornography aimed at high schoolers.

I’ve also done books like this on drugs and teen sex. I don’t even know what to say about my life, except that if you had told 12-year-old me that this was how it was going to end up, that kid would high-five you all over the place.

The only time a lay person hears about what goes into a textbook is when some jerkwater school board in North Carolina mandates that they aren’t buying anything with this untested evolution crap in it, or whatever.

I’ve done this about a dozen times (not counting projects I ultimately passed on because the money or timing were wrong). And I gotta tell you, the editorial guidelines have never remotely approached that kind of political micromanagement. More than politics, “expedience” and “balance” are the rule. [3]

What Goes in the Book

The publisher I work with has a lot of conditions defining a “usable” article. Each has to be a certain length, no more than a certain number of years old, and originally published by someone who can and will (maybe) sell reprint rights for the work. It’s best to avoid articles with lots of certain swears and racial epithets, as those will need to be edited out and that can be kind of a headache [4]. It’s also best to avoid anything with too many important graphics or vital footnotes (as these introduce headaches in layout).

Some articles that fit within the explicit conditions end up not being usable because of an evolving set of implicit sub-conditions: problems with whoever actually owns the rights, or conflicts with other series the publisher sells, or weird beefs with competing publishers, and so on.

Even after articles have been cleared (which happens when I submit a proposed table of contents – on spec, incidentally) and undergone the editorial massage, they still might get spiked during production for reasons I’m not told and cannot fathom, with no apparent pattern.

The online porn book lost a pair of articles about whether porn was especially racist, as well an ultra-right wing Christian anti-porn article. No explanation.

A book on teen sex mysteriously lost a politically neutral, but really moving, first-person account of going to an abortion clinic. A book I did on Chernobyl lost a fantastically ironic propaganda piece from a Soviet magazine talking about how rad it was to live in Pripyat, published just months prior to the accident.

The point here, though, is that none of the conditions guiding what I choose, or what ends up in the textbook, are political litmus tests. I’m not saying it doesn’t happen – just that I haven’t seen it. And based on how I see these publishers operating, I imagine it is more the exception than the norm.

The Real Work

To find the Magical Dozenish Pro-Con Pairs for one of these books, I dig up, read, sort, and reject several hundred books and articles, including op-ed pieces, newspaper stories, trade journal articles, TV/radio transcripts, academic bloviation, hysterical non-fiction trend books (“Pornpocalypse: How Rule 34 and Turning Off Google Image SafeSearch is Destroying the American Family and Empowering the Hand-lotion Industrial Complex”), blog posts – whatever I can find.

FYI, the bulk of the work in producing one of these textbooks is this stage: just the searching and sorting. Putting together a proposed table of contents consisting of two-dozen usable articles constitutes at least three-quarters of the work in producing one of these manuscripts. (And that part of the work is unpaid; I only get my contract and first payment after they’ve accepted the proposal.)

All the rest of the stuff I have to do – writing intros and discussion questions, editing each article so that it’s the right length and has appropriate subheads to guide the reader, de-jargoning the academic stuff and clarifying the author’s references to Monica Lewinsky [an intern under President Bill Clinton, with whom he did not have actual sexual relations] and “Deep Throat” [an American pornographic film released in 1972, and noted for its use of actual elements of plot, narrative, and character development] with little bracketed asides – that stuff takes me no time.

But finding the pairs of articles that fit all the conditions? That’s a crazy, often morally harrowing quest.

Finding the Grail Two Dozen Times

That’s not to say it’s all battling dragons in the depths of the MELcat inter-library reserve system.

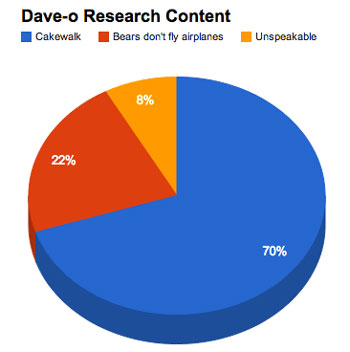

About 70% of the table of contents writes itself: You cast your net wide, and just pick out the sweetest, ripest, juiciest hysterical pro/con articles. For example, filling the “It’s stupid to prosecute teens who sext as if they’re child porn merchants” was a cakewalk; articles were fighting for that slot. Lots of great writing there.

The next 22% percent is a little tougher. For example, plenty of people want to say “Watching online porn causes erectile dysfunction in young men!”, but very few people bother saying, “No, it doesn’t” – because, you know, that’s basically self-evident:

- The majority of young American men masturbate while looking at Internet porn.

- The incidence of ED in young men is astronomically low.

- Ergo there is no cause/effect demonstrated. QED.

It’s the same reason not a ton of op-ed pieces are written about how bears don’t fly airplanes; they just don’t, for god’s sake. There’s no evidence they do, there are no statistically significant reports of bears doing so, few people assume bears do. And also: They don’t.

That’s the next 22% of the job: Finding the “bears don’t fly airplanes” articles. That’s harder, but it isn’t the final 8%. The last 8% constitutes the bulk of my research time on these projects, which is a few months of casually looking for stuff when I have a free moment, followed by about three weeks of doing almost nothing but research, and that research is out in the Internet’s dark, weird boondocks.

The last 8% is finding articles like “Child pornography is good and great and wonderful!” But I can’t use just any old boob saying something insanely contrarian and, often, morally reprehensible. The boob has to spend at least 1,000 words saying it, has to do it in a cogent manner, has to not swear a shit-ton while doing it, has to do so under a name and published in a way I can actually reference, has to have published the piece within the last five years (preferably three years), has to be willing to be found so the publisher can pay him for reprint rights, has to be writing for a publication that I haven’t already used in this book and hasn’t been used in any other similar book in this publisher’s line within the last few years . . .

The list goes on and on, and those are just the visible conditions. I’ve had stuff pulled from a table of contents because, as it turned out, a specific author was just a total jerk and the publisher didn’t want to deal with him or her ever, ever again. No one puts that on the spec sheet for a series; it just sorta comes up.

Lots of little things just sorta come up, but they’re all mundane and petty and tiny. What some dudes in North Carolina think about the sin of evolution? That’s never been one of them.

Anyway, going for that last 8%, you go deep, and that’s when you turn up the real crazy gems. This month’s Chronicle column originally opened with an excerpt from one such gem, a wonderful, terrible, fascinating excerpt from an academic paper published in a peer-reviewed journal – an article that I turned up while doing the research for the Online Porn Classroom Reference, and which stopped me in my editorial tracks. Sadly, the fuddy-duddies here at The Chronicle deemed my excerpt of this fantastic gem too “gah!” for publication.

What are you missing? I’ve been advised to “tread cautiously” here, so I’ll go only so far as to say that it’s about what one hopes is a very unconventional mode of spreading a common and curable sexually transmitted disease. These authors of the paper note that it’s “likely that this mode of transmission is underestimated” because doctors are maybe shying away from asking a super-awkward question. [5]

This article – I had absolutely no use for this article – but you can imagine the kind of Rule 34 insanity I was plugging into Google when this fella popped up.

It didn’t go into the textbook for the same reason it got spiked from this column: Maybe it was fascinating, but it was off-topic, pretty squicky, and likely would have triggered some bizarre copyright nightmare. It wasn’t that any of us had a meaningful agenda, it’s just that it was easier to leave it out. Besides, we already had plenty of stuff covering this topic.

So, this is my normal workday. This is how the textbooks get made.

Notes

[1] But don’t fret: We’ll return to link-choked screeds and thousand-word-footnote territory next month! Promise!

[2] Patrick Stewart – duh! Will Shatner would never kiss me. Zing!

[3] You might argue that “expedience” and “balance” are political, and I hear that, but respectfully disagree. They aren’t political, just lazy, and I’ve found that we are equally lazy at all points along the American political spectrum. For more on our cultural “laziness bias”, I strongly advise reading Al Franken’s excellent (if kinda-sorta dated): “Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them.”

[4] This one became super awkward working on the Teen Reference to Online Porn, because the titles of many modern porn products are really terribly offensive, but involve no single word that is itself verboten. Arrange the words in the title alphabetically on a page and it’s totally benign. But the title itself? The Dalai Lama would punch you in the mouth for saying it aloud in mixed company.

[5] If you, as a consenting adult, should happen to want to see this textual wonder, please feel free to email me directly and I’ll send you the spiked portion of this column.

The Chronicle relies in part on regular voluntary subscriptions to support our publication of local columnists like David Erik Nelson. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. So if you’re already supporting us on a regular basis, please educate your friends, neighbors and colleagues about The Chronicle and encourage them to support us, too!

I have two questions. You don’t say much about peer review. Any old yahoo can publish anything they want, but in my field we tend to give greater weight to articles published in reputable places. Is that a consideration?

I had the impression that the political process happens after publication, when a committee of anti-scientists in Texas decides which textbooks will actually get bought and used by the schools. How big a factor is that?

Hey Jim, thanks for asking! We’re asked to seek out “high quality” sources, which means different things in different contexts. Personal blogs and highly ideologically slanted publications tend to be considered lower quality, but also have their place, esp. when I need to come up with a first-person account of an event or experience.

One of the problem with peer reviewed sources is that the writing tends to be *terrible*, which makes them a lot of work to clean up and make high-school (or even just human) readable. They also tend to run *really* long (I’m supposed to keep articles between 1,000 and 3,000 words; most academics can’t say *Hey baby; where you going after this?” in less than 5,000 words and 47 footnotes). In the Online Porn book I ended up using several articles from peer-reviewed journals because it was the only way to responsibly include some pretty controversial views. For example, I used an excerpt of Diamond, Jozifkova, Weiss’s “Pornography and Sex Crimes in the Czech Republic” (first published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior), in which the researchers found a correlation between unfettered access to pornography (including child pornography) in the Czech Republic from 1971-2007 and marked *decrease* in all sex crimes, especially sexual violence targeting children. A claim like “broad access to kiddie porn decreases new sex crimes against children” is pretty insanely inflammatory, and so including it really called for tracking down the most unimpeachable possible source.

As for the mechanism of political pressure in textbook publishing: You’re right that the pro-Jesus-ate-a-pteradactyl Texans only enter the scene *after* a book is published (to the best of my knowledge, at least; I’ve never heard of a politically motivated group seriously approaching a textbook publisher in advance to guide content creation in what is otherwise being sold as a secular, impartial textbook). But the fear I often hear reiterated in the media is that these after-the-fact complaints will guide what happens in the next revision. All *I’m* saying is that I’ve *never* seen any evidence that “market pressures” of these sorts politically bias what ends up in a textbook. On the other hand, restrictive reprint policies from folks like the Journal of the American Medical Association or individuals like Andrea Dworkin basically guarantee that their work (or work they shepherd) won’t end up in a textbooks, and that can be a real shame.

Damn! I always thought you just did creative writing — off the seat of your pants. You make most things so amusing, and now you’ve shown us the work.