Column: How to Count to 8, Stopping at 6

The Ann Arbor city council’s vote last Monday on the appointment of Al McWilliams to the board of the Ann Arbor Downtown Development Authority was 6-5 on the 11-member body. A 6-5 vote for the Ann Arbor council is rare, and reflects a certain amount of controversy surrounding McWilliams’ appointment.

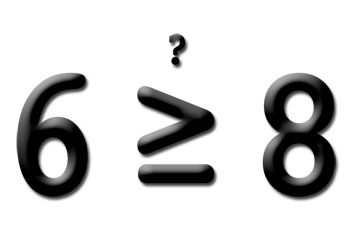

But in this column I’d like to leave aside the controversies that led to such a narrow split. Instead, I’d like to review the history of the legislative actions that led up to the 6-5 vote at the council’s Sept. 16, 2013 meeting. That review leads me to conclude that eight votes should have been required for approval.

A quick narrative summary goes like this: McWilliams was set to be nominated, then not actually nominated, but then nominated after all, then had his nomination “withdrawn,” and then finally had his nomination voted on by the council. But in the end, the six-vote majority was declared enough to confirm his membership on the DDA board, replacing Newcombe Clark, who made an employment-related move to Chicago after serving one four-year term.

Choice of the phrase “was declared enough to confirm” is not accidental. Even though the tally of six votes was deemed sufficient by the city clerk and mayor John Hieftje for approval of the motion, I think the vote actually required eight votes to pass.

Under the council’s rules, a nomination to a board or commission can’t be confirmed or approved before the next regular meeting of the council – unless eight members of the council vote for the confirmation. So the typical pattern is that a nomination is put forward at one meeting and the vote on confirmation is taken at the next regular meeting.

Hieftje explicitly stated at the council’s Sept. 3 meeting – during deliberations – that he was withdrawing the nomination of McWilliams. The matter was not “postponed” – as Hieftje described it at the Sept. 16 meeting – because the council did not vote on the McWilliams nomination at all, much less vote in a way that postponed consideration. It certainly would have been an option for the council to have entertained a motion to postpone. But councilmembers did not wind up voting on it at all, and Hieftje stated: “Okay, so I will withdraw it [McWilliams' nomination] tonight.”

Under any rational understanding of the nomination and confirmation procedure, Hieftje needed to take some affirmative action to put the nomination before the council again, which could have been done at the Sept. 16 meeting. Early in that meeting, during communications time, Hieftje indicated to the council he’d be bringing McWilliams’ nomination forward toward the end of the meeting, when nominations and confirmations are handled. The nomination was not on the council’s agenda as of 4 p.m. that day and came as a surprise to some councilmembers.

But instead of just placing the nomination of McWilliams before the council, Hieftje also asked the council on Sept. 16 to vote on confirmation, which it did – with the 6-5 outcome.

It’s puzzling that the online Legistar file for Sept. 16 containing the McWilliams nomination states that the nomination was “placed on the table for [the council's] consideration at the Sept. 3, 2013 Regular Session.” Reviewing my own notes, The Chronicle’s reporting and the CTN video, I can’t discern anything that happened at the Sept. 3 council meeting that could reasonably be described as placing McWilliams’ nomination on the table for consideration. Certainly councilmembers were asked to vote on Sept. 3 on a nomination that had been put before them on Aug. 19. But at the Sept. 3 meeting, the nomination was withdrawn by Hieftje for consideration by the council. And the Legistar record from Sept. 3 accurately reflects that: “Appointment taken off the table on 9/3/13.”

It’s certainly contemplated by the council’s rules that a nomination and confirmation vote can take place at the same meeting. So asking for the vote on Sept. 16 did not violate the council’s rules. It’s just that the 6-5 outcome on that vote should have been judged as not confirming the appointment of Al McWilliams to the DDA board – because it needed eight votes.

The problem here is not just a technical one. What’s the rationale for a higher voting threshold when a confirmation vote comes at the same meeting as the nomination? Granted, I think part of the rationale is to ensure enough time for an adequate review and vetting of a candidate – which arguably took place in the case of McWilliams’ nomination. But part of the rationale is not peculiar to appointments to boards and commissions. At least part of that general parliamentary principle is this: A higher standard is imposed when less notification has been given to the members of the council (and to the public).

When Hieftje withdrew McWilliams’ nomination at the Sept. 3 meeting, I think councilmembers and the public could have had a reasonable expectation that they’d be notified of an upcoming vote on his confirmation at least one meeting before a confirmation vote was taken. Absent that notification, the threshold for a successful vote should rise – to eight.

In this column, I’ll lay out some of the documentation in the online Legistar files that makes clear that the Sept. 16 nomination really was considered a new, fresh nomination that should have required either an eight-vote majority or a delay on voting until the following meeting.

I also have a suggestion for a remedy that does not involve Miley Cyrus.

Legistar Files

In the city’s online Legistar system for management of meeting agendas, mayoral nominations and their associated confirmation votes – which are typically taken at a subsequent meeting – are handled with the same file. That’s accomplished by using the “version” feature of files. For example, a file gets set up with a number in the format 13-xyzw. In Version 1, the nominations are listed out, usually with some text at the top like, “I would like to recommend the following nominations for your consideration.”

On the subsequent meeting agenda when the vote is taken, the same 13-xyzw file is used, but the version is updated so that in Version 2 we see the same list of people with something like “I would like to request confirmation of the following appointments that were placed on the floor for your consideration at the [date] regular session.” Legistar lets a user toggle easily between versions of the same file, so it’s easy to see the history.

Typically it’s easy to establish a connection in Legistar between a nomination and the subsequent confirmation – because it’s the same file number with a different “version.” Sometimes a name appears in the nomination version of a file, but does not appear in the confirmation version. Or sometimes the name appears in the nomination version of a file, but the name is simply not read aloud by the mayor at the meeting.

Timeline for McWilliams Nomination

With that background, here’s how the nomination of McWilliams unfolded:

- 08.08.2013 Legistar 13-0959 version 1 McWilliams’ name was not put forward verbally at the meeting. The address listed in that file is the same as his company Quack!Media, 320 S. Main St.

- 08.19.2013 Legistar 13-1001 version 1 McWilliams’ name was put forward verbally at the meeting. The address listed in that file is 551 S. Fourth Ave., and his Facebook page includes one entry describing a move.

- 09.03.2013 Legistar 13-1001 version 3 A vote was requested by mayor John Hieftje on three nominations as a group – two besides that of McWilliams. The question was moved by Christopher Taylor (Ward 3) and seconded by Sabra Briere (Ward 1). Mid-deliberation, the confirmation votes were separated out. And later during deliberations just on McWilliams’ appointment, Hieftje asked that he be able to withdraw the nomination:

If it is friendly I would ask the mover and the seconder to allow me to withdraw this nomination tonight to explore some of these issues and come back with answers. But. Is that friendly? Okay, so I will withdraw it tonight.

The parliamentary step to achieve that outcome was not implemented in strict fashion – something Chuck Warpehoski (Ward 5) pointed out to me in a phone interview. Once a question has been moved and seconded and put before the council, then the question belongs to the council, not the mover and the seconder. It’s an option for the mover of the motion to request permission to withdraw it – but can do so only with the permission of the council.

One proper approach would have been for Taylor to have asked permission to withdraw his motion to consider the question of McWilliams’ confirmation, and for Hieftje, after checking that there was no objection by the council, to have declared that motion withdrawn. If Hieftje had said nothing else, that would have left McWilliams’ nomination in place before the council.

But that’s not the way events unfolded. The problem with the way events actually unfolded was not the failure to conform with strict parliamentary procedure. The rights of the majority and the minority on the council weren’t interfered with as near as I can tell, and the will of the council was that they were content not to vote on the nomination that night. The problem is that the casual mechanism used to effectuate the will of the council gave rise to possibly different expectations for the future status of the nomination.

Warpehoski, for example, told me that based on Hieftje’s Sept. 3 indications about the nomination, he expected that he’d be asked to vote on McWilliams at a future meeting, likely the next one on Sept. 16. Further, he had processed Hieftje’s remarks as meaning that when the question came back, it would be on the same nomination that had been previously made. When the item did not appear on the agenda by the day of the Sept. 16 meeting, however, he did not think the council would be asked to vote on the question that night. So Warpehoski allowed that he was surprised when Hieftje announced at the Sept. 16 meeting that he was bringing back the nomination of McWilliams.

For my part, Hieftje’s choice to state that he was withdrawing the nomination meant that if McWilliams’ name were to come forward again, then it would be as a fresh nomination – distinct from the one placed before the council on Aug. 19, because that one had been withdrawn. I think the withdrawal of the nomination on Sept. 3 as noted in the Legistar file is accurately described – with a strikethrough of McWilliams’ name and the notation: “Appointment taken off the table on 9/3/13″

- 09.16.2013 Legistar File 13-1139 version 1 Early in the meeting Hieftje states (incorrectly) that [emphasis added]:

I would note one thing that I didn’t see on the agenda that uh, the nomination of Al McWilliams was postponed and I will be bringing that forward when it comes time for the mayor’s communications.

When the meeting reaches that point, Hieftje says:

And I would also like to request confirmation of the following nomination that was placed on the table for your consideration, and then it was uh, two meetings ago, and then it was um withdrawn so that we could do some exploration on some issues that were brought up. And that is the nomination of Al McWilliams to the Downtown Development Authority.

The Legistar file states (erroneously) that [emphasis added] “I would like to request confirmation of the following nomination that was placed on the table for your consideration at the September 3, 2013 Regular Session.”

Analysis

What’s key here technically, I think, is the fact that a new file (13-1139) on McWilliams was established for the Sept. 16 meeting. That disconnects the council’s consideration on Sept. 16 of his appointment from the previous nomination on Aug. 19 – for which a different Legistar file was used (13-1001).

Given the oral descriptions at the meetings (that the nomination had been withdrawn), and the legislative documentation in Legistar, I don’t think it’s possible to maintain rationally that any nomination of McWilliams prior to Sept. 16 was still technically or procedurally in front of the council.

Because Hieftje, in practical effect, nominated McWilliams on Sept. 16 and asked for a confirmation vote at the same meeting, the tally should have been required to be eight votes for approval. The council rule is as follows:

RULE 6 – Nominations or Appointments to Boards, Commissions or Committees Nominations or appointments to boards, commissions, or committees, which require the confirmation or approval of Council, shall not be confirmed or approved before the next regular meeting of the Council except with the consent of 8 of the members of the Council.

So the problem is not that the vote was taken on Sept. 16. The problem is that the outcome of the vote was analyzed incorrectly as approving the appointment.

How to Fix It

It would have been ideal if the ruling – that the 6-5 vote was sufficient for the McWilliams appointment – had immediately been challenged at the Sept. 16 meeting. But no councilmember objected at the time. And frankly, that has to count in favor of the idea that the minority didn’t perceive that its rights were being violated at the time.

But I don’t think that insisting on strict application of the eight-vote standard is a case of over-enthusiastic following of rules just to make a technical point. That is, this is not the kind of situation Henry Robert meant when he wrote:

It is usually a mistake to insist upon technical points, so long as no one is being defrauded of his rights and the will of the majority is being carried out. The rules and customs are designed to help and not to hinder business.

One natural upcoming occasion to address the point might be the approval of the Sept. 16 meeting minutes, which will be handled at the Oct. 7 council meeting. The result of the vote on the Al McWilliams confirmation is part of the minutes, and it’s the result that was judged incorrectly.

Stephen Kunselman (Ward 3) has indicated to the city clerk that he plans to vote no on the approval of the minutes for that reason. City attorney Stephen Postema is currently reviewing the matter.

But the minutes of the meeting are supposed to be an accurate reflection of what happened at the meeting. And what happened at the meeting was that the nomination was declared approved. So it would do a certain violence to the historical record if that were simply changed. Still, it might be worth considering an annotation to the minutes to the effect that the result was judged incorrectly and that the minutes as adopted by the council reflect a failed motion to confirm the McWilliams nomination.

That approach would not prevent Hieftje from putting forward a fresh nomination of McWilliams on Oct. 7. The council could then vote 6-5 (or even by some different tally) on Oct. 21 to put Al McWilliams on the DDA board, or not. That is, there’s still plenty of time before the new post-election composition of the council is installed to put McWilliams on the board – in a way that comports with the council’s own rules.

In sum, there’s still an opportunity to establish a clean, accurate, uncontroversial legislative record, which would attest that the procedure for putting McWilliams on the DDA board didn’t violate the city council’s own rules.

Coda

Updated Sept. 19, 2013.

Earlier I’d inquired on this topic with professional parliamentarian Coco Siewart, who provides consulting services to municipalities as well as the Michigan Municipal League on issues of procedure. She appeared before the Ann Arbor city council earlier this year during a work session to give advice on rules, speaking time limits and working collegially as a group.

I did not ask Siewart to weigh in on the question of whether of an 8-vote majority was required in the case of the McWilliams confirmation vote. I inquired with her as to the options that were available, on the assumption that an 8-vote majority was required and that the result had been misstated. Here’s the query about a hypothetical:

Question: A vote is taken that needs an 8-vote super-majority (on an 11-member body) to pass under the council’s internal rules. The presiding officer of the meeting asks for a roll call vote. The outcome of that roll call is uncontroversially 6-5. The presiding officer declares the motion passed. No one objects (because no one realizes that the 8-vote majority is required.) What options are available after that meeting is over? Someone on the prevailing side could bring the vote back for reconsideration. But are there any options available to someone on the losing side? Are there any options available to the presiding officer?

So in Siewart’s response, which arrived today, she’s commenting only on the options available under a scenario when the result of the vote was incorrectly stated at a meeting. She’s not commenting on the question of whether the eight-vote requirement applied to the Sept. 16 Ann Arbor city council vote. Here’s Siewart:

… it appears that in this instance, the vote is not in question but the chair’s statement of the outcome. If action was not taken in response to the motion, the issue could be placed on the agenda for the next meeting and the chair could explain that the result of the vote was incorrectly stated and he/she should have stated the motion lost. If action was taken as a result of the motion, the Council should decide if it is an action that could/should be halted.

(Another note: The word super majority is an invention of the media. A vote is by majority or by 2/3 or by 3/4 etc.)

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public bodies like the Ann Arbor city council. We sit on the hard bench so that you don’t have to. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

Thank you for another very interesting column.

I am also concern about the Mayor’s failure to give adequate prior notice of the consideration of this nomination before his mention of it at the beginning of the September 16 meeting. The lack of prior notice means that the public had no opportunity to submit written comments and no opportunity to schedule a speaking slot at the beginning of the meeting to address the appointment.

If you are correct that the September 16 vote failed for lack of an 8 vote majority, that means the resolution did not pass. I am under the impression that when a resolution fails, it comes back only by motion for reconsideration. Wouldn’t it now require one member of the 5 vote minority to seek reconsideration of the failed resolution?

Jack, I’m understanding your comment to imply something like: A fresh nomination and confirmation vote would be the same as reconsidering the same question – so the path outlined in the column, resulting in McWilliams’ appointment to the DDA board on Oct. 21, wouldn’t be available, unless a member of the prevailing side set that process in motion.

I would counter that by pointing out that the “question” possibly to be considered on Oct. 21 (after nomination on Oct. 7) would technically be different from the question considered on Sept. 16, because they would differ by the date specified for the start of the term of service. So it would not be a reconsideration of the same question to ask the council to vote to confirm his nomination for a term starting Oct. 21, instead of Sept. 3.

I was comfortable thinking that I wouldn’t have to address Council for the purpose of opposing the Al McWilliams nomination. I had assumed the combination of scatological twitter posts, misogyny and conflict of interest would be sufficient to embarrass Mayor Hieftje into dropping it.

Surprise! It was added to the agenda after the Council meeting began. There was no opportunity to sign up for the public comment I wished to offer.

Hopefully, the Mayor will choose a different candidate from Ann Arbor’s rich stable of qualified potential board members. A bit of discretion on the part of the Mayor would spare us the unpleasant task of once again bringing up the poor quality of this nomination.

DDA has a powerful board which is becoming increasing controversial. It needs the supervision of Council instead of the long entrenched practice of rubber stamping the Mayor’s appointments.

Not only is the Mayor ignoring the voters and the public, now he’s apparently ignoring the rule of law too.Trust me Mr. Mayor, they wouldn’t put up with this in Portland or Montreal or Paris or Seattle or Boulder.

Re (2): Thanks Dave. Have you considered augmenting the Chronicle’s income by contracting with the City to act as Council’s parliamentarian?

A cogent analysis. Well done!

One real irony (but not surprise) of this mess is that council agreed in principle at the meeting to submit all agenda items before Friday afternoon preceding a council meeting. It didn’t even last to the end of the meeting to completely fail.

Glad Dave made sure to set the record straight about what needs to be done before the November elections take effect.

The large sucking sound you hear is the sound of all the things being jammed onto the agenda before then.

Thanks for the article.

Simply amazing.

A flagrant and wholesale disregard of the Council Rules.

I thank David for this in-depth analysis and sincerely hope that something is done about this travesty of government that has been perpetrated by the Mayor.

And where was our City Attorney Postema in this mess? Did he cheerfully rubber-stamp this episode?

I hope A2 residents wake up to see how they are being victimized.

I do think this is a grey area, I don’t think it qualifies as a flagrant violation.

Let’s step back: there’s procedure and principle here. As far as procedure, I don’t see a violation. Rule 6 says nothing about motions. It just establishes that it takes 8 votes to confirm a nomination if that’s the first meeting at which Council sees it. When council received notification of a nomination, there is no motion, it is just entered into the record. The actionable motion takes place at a subsequent meeting. By my reading of Rule 6, at any meeting after notice of nomination, a motion to approve that nomination requires the standard 6-vote majority (presumably this would be interpreted to apply to any meeting within the same legislative session).

That’s my read on the procedural letter of the law, then there are the principles at hand. I think there are several:

The core parliamentary principle is to have a process by which the rights of the minority are protected while enacting the will of the majority. This principle applies to the members of the deliberating body, and Dave argues above that this principle does not appear to be violated. Both members of the majority and minority had researched the candidate and were able to come to the meeting prepared.

There is another principle at play here: no surprises. Let me note, this is a principle of collegiality, not a parliamentary principle. Parliamentary process allows for all sorts of surprises. As an example, a resolution can be introduced from the floor and voted on that night without triggering the eight-vote rule.

Council did that a few weeks ago when a settlement agreement was added to the agenda and voted on at the very end of the meeting. I had not seen the text prior to the meeting, the public was not aware of it. It was clearly a surprise, but not one that would have required 8 votes to pass.

That said, “no surprises” is still a good operational guideline for both the members of the assembly and for the public, especially for controversial items. The settlement above was not controversial, the McWilliams is, and there is a case to be made that the late addition of the McWilliams nomination to the agenda. Again, that he was nominated was not a surprise to me or to the many Council members who took the effort to contact him and research his appointment, but the timing was a surprise.

Finally, I do think there is another fair play principle that should be brought up: not using absences to defeat a controversial proposal. When the DDA amendment was brought up in April, Sumi had to leave the meeting early (as in, before 3am). I think it would have been inappropriate to use her absence to push for a vote that night and defeat the resolution. Again, parliamentary procedure allows it, just as I believe it allowed the vote on Monday, but I don’t think it helps group process.

Chuck, your description of the nomination is accurate, but actually lends support to the conclusion that the eight-vote requirement applied. Specifically, “When council received notification of a nomination, there is no motion, it is just entered into the record.” And to be precise, a “notification” is accomplished through an oral statement. Otherwise put, a nomination is effectuated through a performative speech act [in the sense of J.L. Austin]. It’s the same category of utterance as “I take this woman to be my wife” or “I name this ship the Edmund Fitzgerald.” Even if the pink sheets printed out for the council contain a person’s name for nomination, if it is not read aloud, then that person has not been nominated.

Similarly, I think that the only rational understanding of Hieftje’s explicit statement – that he was withdrawing the nomination – was that he engaged in a performative speech act to undo the previous act of nomination. He need not have said that, if what he wanted to do was to avoid a vote. He could have suggested that Taylor ask for permission from the council to withdraw his motion to confirm McWilliams. The council could have assented. And that would have been that. Instead, Hieftje undid his nomination in the same manner in which it was initially placed before the council – through a performative speech act. And that was accurately recorded in the public record – with McWilliams’ name struck through, and the notation that the appointment had been taken off the table.

I think it’s important to understand the distinction between (1) knowing that Hieftje was likely to try again to get the council’s confirmation of McWilliams to the board and (2) having McWilliams’ nomination procedurally in front of the council.

Chuck, if you have an argument that the McWilliams nomination was still in front of the council at the end of the Sept. 3 meeting, after Hieftje stated that he was withdrawing it, then I’m interested in hearing that argument.

As far as the fair play principle of not using an absence to defeat a controversial proposal, I think what we saw unfold on Sept. 3 was an application of that principle. It was Hieftje’s choice to ask for a vote on McWilliams, even though he knew full well that Lumm and Higgins were absent. Even though councilmembers who opposed the nomination could have forced a vote on the motion that was in front of the council – they did not insist on a vote. Arguably part of the reason that there was no objection is that Hieftje stated that he wanted to be allowed to withdraw the nomination.

By violating the basic collegial rule of “no surprises” – perhaps because Hieftje did not have 100% confidence that he’d have six affirmative votes in attendance at any of the three remaining council meetings – Hieftje hoisted himself by his own petard, because in this case a “surprise” carries with it, by council rule, a requirement of 8 votes.

Perhaps the most significant point would be the Horton rule:

“I meant what I said and I said what I meant.”

It is important that process statements are made clearly and unambiguously. If the Mayor said “withdraw”, that’s what should be understood.

If withdrawn – it was not acted on in that meeting, thus the Council was back to square zero on the second time the subject of the appointment was raised.

The column has been updated to include the perspective of a professional parliamentarian on the question of options available now, assuming that the 8-vote requirement did apply: [link]

Regarding the Coda, correct me if I’m wrong, Dave, but I believe that the ruling that “motion carries” was made by the Clerk, not the Mayor as presiding officer.

Regarding what the meaning of “withdraw” is, I had previously been under the impression that Robert’s does not recognize withdrawing a motion. I was wrong. Robert’s allows for 2 ways to withdraw a motion:

1. The mover can withdraw it without any approval necessary before the chair has stated the motion;

2. A motion can be withdrawn my unanimous consent or majority vote;

http://www.rulesonline.com/rror-04.htm#27(c)

Council Rule 10 affirms this practice “When any motion has been made and seconded, it shall be stated by the Chair and shall not be withdrawn thereafter except by consent of the majority of the members of the Council present.”

Note, this only applies to a motion, and since the Mayor asked for permission from the movers of the motion, it could have as easily been interpreted as withdrawing the motion. This interpretation is further supported as they Mayor modified “withdraw” with the word “tonight.”

Since, once moved and seconded, a motion belongs to the assembly, at this point someone would have been in order in objecting to the withdrawal. At which time the motion to withdraw the motion could be voted on, or a motion to postpone could have been made.

So we are left with a semantic argument that I don’t think gets us far. So I go back to the priciples I described before: majority rule with minority rights, no surprises, don’t manipulate absences. Right now my thinking is going into how to have a process or action that affirms those principles.

Re: [13] “Regarding what the meaning of ‘withdraw’ is, I had previously been under the impression that Robert’s does not recognize withdrawing a motion. I was wrong. Robert’s allows for 2 ways to withdraw a motion”

Right. And the way the withdrawal of a motion works is described in the column; it factors into the clear argument in the column against the idea you promote – that what happened was only a withdrawal of the motion, as opposed to the nomination.

Specifically, you assert: “… since the Mayor asked for permission from the movers of the motion, it could have as easily been interpreted as withdrawing the motion.”

I don’t think it could be interpreted that way at all, and certainly not easily, and especially not by you at the time, Chuck – because you did not believe at the time that Robert’s Rules even recognized the concept of withdrawing a motion. So to you it must have been completely nonsensical.

I’m not sure what you mean by a “semantic argument” because what you’re posing is a syntactic question. What is the object of the verb “withdraw” in the sentence: “I would ask the mover and the seconder to allow me to withdraw this nomination tonight.”? Chuck, your position appears to be that it’s really hard to tell what the object is of the verb “withdraw”. I don’t think it’s hard to tell. The object of the verb is “this nomination.” Where’s the ambiguity?

I think you’re still not quite grasping the distinction between the mayor’s role and the councilmember’s role in this procedure. It’s for the mayor to nominate someone with a performative utterance along the lines “I’d like to place before the council the following nominations …” That happened on Aug. 19. Typically, at a subsequent meeting, a councilmember moves the question, it gets seconded, and the confirmation is then before the council. That happened on Sept. 3. Now, on Sept. 3, the mayor asked permission to do something after the motion was before the council. That’s uncontroversial. What was that thing? You claim it’s possible that the mayor’s request could be interpreted as meaning that he wanted to be allowed to withdraw Taylor’s motion?? That’s just nonsensical. The only rational thing that the mayor could be asking permission for himself to do in this context is to undo the thing he’d done himself through a performative utterance on Aug. 19. Specifically, he asked permission to withdraw the nomination, was granted permission and then did so.

The obviousness of this understanding is reflected in the public record in Legistar that strikes through the nomination and notes that it was taken off the table.

If you do not believe that saying, “I’ll withdraw the nomination tonight,” actually removes the nomination from consideration by the council, what action do you believe would accomplish that? Otherwise put, let’s say it’s the intent of the mayor to remove a name from consideration that had previously been put before the council – so that it’s clear to everyone that the council won’t be asked to vote on it at a subsequent meeting (unless the nomination is placed before the council again.) How else could he possibly do that except to say to the council at a meeting, “I’m withdrawing the nomination of [person name] to the [board name] tonight.”?

Re: “This interpretation is further supported as they Mayor modified “withdraw” with the word ‘tonight.’” ?? I don’t see how. If you want to flesh out that as an argument, I’d be interested in hearing it. I think the addition of the word “tonight” pretty well pins down the interpretation that it’s the nomination that has been withdrawn. Paraphrase: “I’ll withdraw the nomination tonight, but may put the nomination before you again.” That’s fine, and if the nomination is put in front of the council again, then it needs to wait another meeting for a vote, or else achieve an eight-vote majority.

Re: “… correct me if I’m wrong, Dave, but I believe that the ruling that “motion carries” was made by the Clerk, not the Mayor as presiding officer.” On a roll call the clerk administers the call of the council tallies the vote and reports it to the mayor. But it is for the mayor as presiding officer to affirm the outcome officially. That’s your Council Rule 5: “In all cases where a vote is taken, the Chair shall decide that result.” So what you typically see in the minutes on a roll call vote is: “On a roll call, the vote was as follows with the Mayor declaring the motion carried.” Reviewing the video, on that occasion, Hieftje simply said, “Thank you,” not his usual, “It’s approved,” or “It passes.”

So if it comes to formulating the verbiage that goes into the annotation of the minutes, to the extent that the error is attributed to a person, that person, by Rule 5, would be Hieftje, I think.

The remedy that’s proposed in the column – annotation of minutes with declaration of failed vote, nomination on Oct. 7, confirmation on Oct. 21 – respects your desire, I think, to have a process to remedy this that respects: majority rule with minority rights, no surprises, don’t manipulate absences.

My prediction is the city attorney’s office says something along the lines of: Under the DDA statute, it’s for the governing body to appoint members of the DDA board under its rules, so it’s the council rules that are at issue and their interpretation, and because the matter here concerns a council rule, what was said and documented can be interpreted in the manner that the council as a body wishes to interpret it, and can be addressed now or remedied in some fashion if that’s the desire of the body, and it can do so in the manner that the council as a body deems suitable.

The big issue here, which has been touched upon tangentially above by Messrs. Eaton and Zetlin has been the confirmation of McWilliams with no previous notice to the public nor opportunity to be heard prior to the vote.

A clear issue is Open Meetings Act non-compliance.

Re: “A clear issue is Open Meetings Act non-compliance.”

Which section of the OMA do you think was violated?

The Open Meetings Act has requirements for noticing meetings of public bodies and requires an opportunity by members of the public to address the public body. But there’s no OMA prohibition against adding an item to the agenda from the floor at a meeting. And there’s no requirement that the opportunity to address the public body has to come before the body votes on a particular matter.

Which is not to argue that it’s a good idea to spring things on the council and the public so that the effect is to deprive the public from an opportunity to comment on a matter. It’s just that I really don’t think it’s an OMA issue.

@18

Agreed.

There is a case from the Michigan Court of Appeals that likely provides authority for your position: Lysogorski vs Bridgeport Charter Township, 256 MichApp 297 (2003) where a person appearing at a board meeting was denied the opportunity to speak on an issue that arose during the meeting due to a rule limiting public commentary to the beginning of the meeting.

As to “public hearings” the rule is different and Haven vs City of Troy held in an appeals opinion that public notice of a hearing implies the requirement that the topic of the hearing be imparted within the public notice so that the public may appear to give commentary on the issue to be heard.

While I believe Lysogorski is bad law and bad public policy, it is binding on our lower courts in Michigan.

Well done, Dave. Thank you for being the watchdog of our community. I do, in fact, sleep a little tighter at night, knowing that The Chron is awake.