In it for the Money: Your Public Library

Editor’s Note: At the Ann Arbor city council’s March 17, 2014 meeting, Ann Arbor District Library Director Josie Parker told councilmembers that heroin sale and use takes place at the downtown location of the AADL. The council was debating a resolution about reserving as a public park an area of the surface of the city-owned parking structure adjacent to the downtown AADL.

In rejecting the idea that the problems are caused by the homeless, Parker also told the council that “some of the most obnoxious behavior exhibited at the public library in Ann Arbor is done by persons who are very well housed, very well fed, and very well educated. It is not about those things. It is just about simply behavior.”

Chronicle columnist David Erik Nelson is a frequent visitor to the public library. He drafted this column before Parker made her comments. And he’s still an enthusiastic library patron. From Parker’s March 17 comments: “We manage it and you don’t know about it … and you’re generally as safe as you can be in the public library, and that makes it successful.”

Say a precocious child – like Glenn Beck, for example – asks you how much the library costs. The library is, after all, readily confused with a bookstore (because it is full of books) or NetFlix (because they let you have stuff for a while, but expect it returned in good condition).

What’s your answer?

Probably the first thing that comes out of your mouth is that it’s free – which makes sense to the child (and, evidently, Glenn Beck). After all, the kid never sees you pay anyone there, and (assuming your household finances are like mine) it is also likely often a place you go to have fun and get stuff after you’ve explained that you can’t buy this or pay to visit that on account “We don’t have the money for it.”

But we’re all grow-ups here – even Glenn Beck – and we certainly know that the library costs something [1], we just don’t know how much (or, evidently, who foots the bill). If pressed, we’d wave our hands and say that the library is probably funded (note that passive voice!) by some sub-portion of a portion of our property taxes, plus a little Lotto money and tobacco settlement, multiplied by the inverse of some arcane coefficient known only to God and the taxman, or something – yet another inscrutable exercise in opaque bureaucracy.

But it’s not that way at all.

In contrast to pretty much all other public services – which are funded by an exceedingly hard-to-parse melange of federal, state, local, and “other” revenue streams – more than 90% of the Ann Arbor District Library’s budget comes from local property taxes. The amount you pay for it is written out on your tax bill.

At first glance, it’s probably more than you would have guessed: The average Ann Arborite has a $155 annual library bill. That’s sorta pricey for something that’s “free.”

But upon even brief reflection, it’s pretty clear that the library is much better than free.

The Cost of Everything

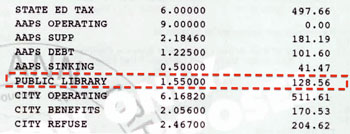

So, here’s my summer tax bill (which is when you pay your library bill – in the summertime). Check out line six.

This year’s library bill was exactly $128.56. [2]

So, that’s about $11 per month. But is that a good deal?

Your average new trade paperback sells for $15 to $20. Even if Amazon knocks off 30%, I’m still looking at at least $10.50 per book (plus shipping). So, if I borrow one book per month from the AADL, I’m doing OK. [3]

I live in a four-person household; the baby (who turned two at the beginning of this month) doesn’t take out books yet (we’re trying to restrict her destruction to private property), but I don’t think my wife and 7-year-old son have ever returned from the library with fewer than three books each. So, just between those two, we often make back our entire annual contribution each month. If an investment consistently pays off at 10% annually – which is to say you start the year with $1 and end it with $1.10 – that’s a great investment. How do you even describe an investment that annually pays off 1,100%?!

Forget BitCoin; put your money in libraries, kids!

But “book rental” isn’t really a thing these days. A much more straightforward comparison would be a commercial endeavor like NetFlix – which is a pretty reasonable comparison, given that about half of the AADL’s annual circulation is “A/V materials” (predominantly DVDs).

NetFlix’s lowest pricing tier for service that includes a physical DVD (rather than streaming only) is $7.99 per month, for which you get one DVD at a time. My experience is that the turnaround time on a DVD is at least three days, and usually we don’t get around to watching a DVD for a day or two. (Remember: two working people, two kids, and we’ve got all those damn library books to read!) So, figure we watch four DVDs per month. Maybe you are a happy single person with few demands on your time. Given the limitations of NetFlix’s shipping schedule, the USPS, and the calendar, you still likely max out at around 7 DVDs per month on this plan.

Meanwhile, the AADL lets you take out an unlimited number of items simultaneously and has an average fulfillment time on requests of one to two days. Also, you’ve already paid for your library, and they offer a lot more than just “Nacho Libre” and “Eight is Enough” on DVD.

A Value Multiplier

As AADL Associate Director Eli Neiburger eagerly pointed out over cookies and coffee one Friday morning, “The library is very unique among taxing entities, in that you pay a flat fee up front, and then the value you receive from it is in direct proportion to how much you choose to use it, with no additional cost required.”

If you don’t feel like you’re getting a good value for your 1.55 mill tax [4], then there is a bone-headedly easy remedy: Borrow more books. Don’t like books? Then borrow movies and music. Don’t like any of the library’s 434,729 items? Then ask for something you do like.

In the same month that I glanced at my summer tax bill and wondered whether $128 was a good deal, the AADL loaned me a pair of digital oscilloscopes – $500 in gear, delivered to within a mile of my house, and free for me to use basically until someone else needs it. If that was the only thing I got from the library in four years, I’d still break even.

You’re likely wondering why the library (an institution named for the books that are its raison d’être) had one – let alone two – oscilloscopes to lend out to me. [5]

And, the short answer is: They had it because I asked for it.

The Most Responsive Entity

I don’t mean to imply that the AADL bought these scopes just because some big important local newspaper columnist asked. Mine was only one of a small handful of patron requests for oscilloscopes. But chatting with staff over email, I was given the distinct impression that even a single sufficiently impassioned request might well have triggered the purchase. That’s because there was already a strong sense from within the library that an oscilloscope might be something their patrons would want, if they knew it was there for the asking.

“We’re here to meet patron demand.” Eli says, with that “we” clearly meaning libraries in general, not just the AADL. “Typically libraries get in trouble when their vision of patron demand drifts from the actual patron demand. [...] What our users want is what we want to get. That’s the mission of the library: To get people the stuff they want. If anything, the 21st century’s biggest problem for libraries has been a ‘faster horse’ problem [6], that they [patrons] may not know what they want.”

Eli was quick to clarify that he wasn’t implying that the AADL should be a nanny telling patrons what they should want, but that any library is constantly bumping up against the limitations imposed by having libro embedded in their name.

According to Eli, “libraries were never in the book business, that was just the cheapest and easiest way of distributing information. To me, the value of the library has always been that it aggregates the buying power of the community and it purchases shared access to things [for private use]. There are no other institutions that have a mission like that.”

Do you want free music? Then the library wants you to have it. [7] Do you want a telescope? Come and grab one! Wanna rock out on a drool-worthy array of synths? BOOM!

“The pressure from the taxpayers helps keep it focused, in that [they ask] ‘Are you adding value for my money?’ – and because the central conceit of the library [...] is you buy it once and you use it many times.”

Libraries and the Creation of Stuff

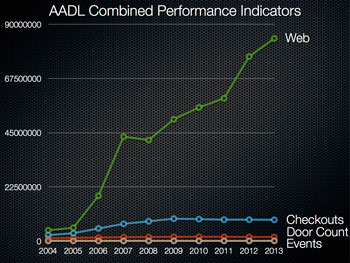

So, that’s the most obvious bang for my buck: My annual payment of something-like-$128 goes to buying several hundred dollars in oscilloscopes – or whatever other reasonably useful things patrons might think to want. But the library isn’t just an aggregator of stuff. Check out the usage chart. (In case you want a little more context, that slide is drawn from this deck, prepared by the AADL.)

What do we see here? Well, since 2006 most of what the library does has held steady: Circulation (i.e., “checkouts,” which number around 9 million annually), folks visiting the library (“door count”), and event attendance are steady.

But “web” (that is, views of AADL web pages) has quadrupled. Why are so many people visiting the AADL web site? Isn’t it basically just a digitized card catalogue?

No. Check it out: “One of the best things we can do with the public money is cause new things to exist on the web that never would have existed otherwise, for which there is no commercial use case,” Eli said.

Eli rattled off several examples – including digitization of the Ann Arbor News archives, which amounts to salvaging, preserving, and disseminating 174-years of small-town history that just happens to coincide with the entire history of Michigan as a state and the growth and flourishing of one of the world’s preeminent research universities.

Or consider the AADL’s partnership with the African American Cultural and Historical Museum of Washtenaw County. Here’s how Eli describes it:

Once or twice a month we set up our equipment and we record an interview where a member of the museum interviews a member of the community and we put the entire unedited video up online with a clickable transcript and professionally done meta-data. There’s not a world in which that makes business sense. The library has an opportunity to make things happen that otherwise would not have happened without the library’s resources. And those things, they don’t just have value now or next week or next month, we seriously think about some of the things we produce having value in hundreds of years.

It’s ludicrous to think that something you upload to Facebook is going to be available to a scholar 500 years from now. But something that you put in the library’s corpus just might be. Of course, there’s a lot of zombies and barbarians and alien invasions between here and there, but, you know, we honestly think about [that] when we put up our infrastructure – we don’t say we want to ‘put it in the cloud and host it on a server.’

We need to know where it is, we need to know how it’s formatted, we need to be responsible for making sure that the data survives catastrophic events and that it can be recovered by people far in the future who we can’t imagine what their tools are. Now, that’s a very serious role, it’s an important part of a community, but it’s a very small part of what the library does, both in terms of hours and in terms of dollars. But does our copy of “Nacho Libre” have long term value to the community? No, it has short term value to the community. But our copy of an interview that would not have otherwise existed, and which we’re pledging to keep on the Internet for as long as we exist and as long as the Internet exists, that has enduring value.

In other words, the library has become a somewhat unconventional publisher – and it only takes a tiny sliver of your $130-ish per month to fund that quixotic endeavor.

Later in our chat Eli characterized it like this: “The 20th Century library brought the world to its community; the 21st Century library brings its community to the world” – which nicely brings us around to the last major thing the library does for us.

Soft Diplomacy

Let’s face it: As a nation, we don’t necessarily have a super-great reputation throughout the world. So, there’s obvious value in putting a little effort into telling the world about ourselves and how we live, lest they somehow get the impression that we’re mostly uneducated, unemployable queer-bashing gun nuts.

A little less obvious is what the existence of an endeavor like this tells the world about our commitment to our nation’s core values. “Free” public libraries – that is, those that are entirely and only funded by local taxes, with no additional “use fee” – are a rarity in the developed world, and libraries of any sort are rare as hen teeth in the developing world.

A project like the AADL says nice things about us, because it highlights our attention and commitment to recording, preserving, and disseminating truths about ourselves that may not be entirely flattering. The First Amendment is effectively meaningless if you have the freedom to speak, but no capacity to do so in a way anyone will get to hear. When we fund the library, we are putting tools in the hands of every member of the community, so that they can be heard. It’s us making good on the promises we’ve made to ourselves. In a world where the most common place to see “MADE IN THE USA” is stamped on the side of the tear-gas canister your government’s secret police just shot into a crowd of school children, it’s nice to have a counter example.

But these are edge cases, because even if the mission of the 21st Century library is to bring our community to the world, I’ve still gotta say that our libraries do a pretty good job of bringing the world to us.

The AADL branch that I frequent is the Malletts Creek branch. I can’t speak to the user mix elsewhere in the system, but Malletts Creek is heavily used by new immigrants and resident aliens, who come there not just for CDs and movies and books, but also for the tot time and Internet access and to receive language tutoring and literacy training. Some of these folks are in it for the long haul – political and economic refugees – and others are here for a few years while they or their spouses attend the University of Michigan. In any event, all of them seem to make occasional sojourns overseas, and to maintain connections with their countrymen.

I very much like knowing that, when someone has a bone to pick with America and the things we cause to happen around the world, these folks I meet at the library have enjoyed the fruits of our system, and are thus more inclined to say, “I hear what you’re saying, but you haven’t been to the United States, and I have, and let me tell you: They aren’t like that. They all chip in without batting an eye – even the blowhard jerkwads on talk radio – to make sure that everyone who sets foot on their soil can learn the language, get online, and get their hands on the stuff that it takes to make rich lives. They are as real about their First Amendment as they are about the Second.”

TANSTAAFL

When my first book came out I did a few events at the AADL’s downtown location. I was making small talk with the guy helping me set-up, and said something to the effect of, “I really appreciate you guys putting on so many free events” and he stopped me and corrected me: “It’s not free,” he said, “You already paid for it.”

And it’s money well spent.

Notes

[1] Here’s Jon Stewart’s classic bit on this. The library gag comes in at 2:20. For the Glenn Beck apologists out there who might wanna claim that Beck just slipped up and misspoke that one time, you’ll note that the two clips I’ve shared are from different events; this “libraries are free” malarky was a standard applause line for Beck about three years ago.

[2] Our house – a lovely 1,000-square-foot ranch with 3 bedrooms, 1.5 baths, hardwood floors, and a finished basement – is about 80% of the median home value for Ann Arbor, so we’re paying a bit less than your average Ann Arborite, whose annual library bill is probably closer to $155. It should thus come as no surprise that a non-resident library card costs $150 per year.

[3] There are obviously some assumptions here as to how one uses those books; buying and borrowing are only the same if you are primarily interested in the book as a word-transmission and transport system. I’m not taking into account those books that I mark up and meditate on over time, books that I need to reference repeatedly, or recovering some of a book’s initial purchase price either directly through resale (for which I rely on the excellent Books by Chance), or karmically through trade or gift-giving.

[4] Currently, each property holder annually pays $1.55 per $1,000 taxable value of their home. The taxable value of an Ann Arbor home is around 40% of its market value. So, if you have an “average” Ann Arbor home – the median home value being something around $250,000 – then your taxable value is probably around $100,000, and your annual library bill roughly $155.

[5] It’s not unreasonable for rational readers to wonder why I needed the damn things: I’m working on my second DIY book. (Here’s my first.) This new book is all musical instruments and noise-toys, many of them electronic. Having a digital oscilloscope on my bench has made it an order of magnitude easier to debug and refine my homebrew (and not terribly electronically rigorous) oscillator and filter designs.

[6] Henry Ford apocryphally quipped: “If I’d asked my customers what they wanted, they’d have said a faster horse.”

[7] I was particularly enjoying this album while drafting this column.

David,

I’m puzzled about a couple things:

The quote, “The library is very unique among taxing entities…”

Seems like the parks, trash collection, streets, police services, public schools, most everything else local government does (water and sewer excepted) all have zero marginal cost to the user (fancy-speak for “you don’t pay more to use it more”). Can you elaborate a bit more on why the library is unique in that way?

and the statement, “We never were about books”. If the library’s mission statement “We get people stuff”, how does the library differ from Amazon or iTunes? If you through in Public Radio’s Story Corps, it looks like the world already has everything the library does in hand.

What am I missing?

One last thing: I couldn’t quite tell if Ms. Parker thought it was an issue having homeless people around the library, or not. Was she saying that the “Well housed and well fed” are causing “the” problems at the library (it seemed like syringe litter was “the” problem, but I wasn’t clear about that, either).

Thanks for straightening me out.

I don’t get nearly the value for my library tax “donation” ($236.74) in direct goods, but I agree that it is a good investment. I get community value – knowing that we have the kind of community where kids can read books regardless of their family’s income. Good that it also helps in acculturation of our newer residents.

I wonder how many non-science fiction readers know that TANSTAAFL means “there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch”? (Robert Heinlein evidently popularized it.) A good thing to remember for all services provided by government agencies. We have to put in so that we can take out. But I hope that we never forget that it isn’t just the direct benefit to each of us as individuals that matters, but the benefit to all members of the community. It’s about the kind of community that we want to live in.

I ran across this “Library use value calculator” and keyed a few numbers in. Our household definitely gets more from the library than we pay in.

Replying to Comment #1

John,

Thanks for raising these questions! Eli Neiburger actually addressed most of these when we chatted, but that conversation was 1.5 hours long, so I had to be pretty selective in what I ended up transcribing. At any rate, here’s the understanding I walked away with:

1) PRIVATE USE. It’s sort of buried in the column, but the primary difference is that the library is dedicated to purchasing shared communal access to things for private use. If I take a STOP sign or city-owned truck home, that’s theft–even though there’s a (plausibly valid, nonetheless tortuous) argument to be made that “I bought it.” Yeah, I bought it–we all bought it–but we did so explicitly and exclusively for a very specific public use. WIth the library, we’re communally buying things to be used privately.

2) NO ADDITIONAL FEES. With entities like Parks & Rec, a good deal of their services *do* require an additional fee (e.g., using the public pools or Rec Center, taking classes, borrowing sports equipment, etc.) You can’t *just* pay for (and use) the public parks without paying for Wash Rec and Buhr Pool and all the other stuff that you still have to pay to actually use. (Trash collection is similar, in that there is a cap on how much you can use that service, and there are additional fees applied when you need to, for example, dump a sofa or motor oil. The library is essentially unlimited, save by issues of scarcity itself, and thus scarcity management.)

3) THE INDIVIDUAL CITIZEN CAN MAXIMIZE PROFIT BY CHANGING BEHAVIOR. From a perfectly selfish perspective, one of the nicest things about the library is that, as an individual citizen, I can control how much return I get on my investment. $155 (or whatever) is steep for one book a year, but is actually OK for one book a month–and a steal if I go for the pile of oscilloscopes. I can sorta-kinda do the same thing with Parks & Rec–I mean, I can’t use the bulk of their services without ponying up, but I *could* (confession: *do*–I live by County Farm Park) spend a ton of time in the parks in order to “maximize the return on my parks investment.” It’s not as a great a deal, because a lot of what Parks & Rec does is locked behind a pay-wall (e.g., pools, canoes, basketball courts, ice rinks, etc.), but it’s similar. This becomes a much grimmer calculus when we’re talking about police and fire–I don’t begrudge those ladies and gents a penny, and yet I’m loathe to increase my ROI by having *more* need of their services. In other words, I’m sorta stuck with them.

I want to take a sec to point out that none of 1 through 3 are complaints; different services have to work differently. But the “non-responsiveness” that’s built into those other services is, I’d hypothesis, part of the reason that we so often resent them. On the other hand, the hippie-commie library is *incredibly* popular among Americans (link)–more so than any other part of government. And, I think that has a lot to do with the fact that libraries are, on balance, highly responsive and because we feel that we can make more of our investment by using them more. We have a very strong, unarticulated sense of community ownership of those resources, which is lacking when it comes to police, fire, trash pickup, roads, and all the rest.

4) AMAZON AND ITUNES, STORY CORPS AND MORE: Amazon and iTunes are *excellent* at distributing information–as are Project Gutenberg, and Archive.org, and NetFlix, and YouTube, and Blockbuster (oops!), and Borders (oops!)–which I guess brings me to my point, which is that commercial endeavors and ad hoc communal endeavors are very *fragile.* I worked in customer service at Borders’ corporate offices at the tail end of their hay day, and I can tell you for a fact that in many communities–esp. in rural America–a Borders store, with that really remarkable depth of stock and fulfillment service, was much more of an asset to some subsections of their communities (e.g., and I mention this because it came up often, queer and questioning teens) than their local and school libraries. But Borders fell, because in the end no for-profit entity is truly built for longevity; it’s built for profit. On top of that, these endeavors are also highly unreliable: material is pulled from NetFlix constantly, and new material added. Their collection is driven by factors other than user demand or need or import; in fact, it’s often driven in ways that have nothing to do with either the content, it’s creators, or the users: When NetFlix has a falling out with a big rights holder, a bunch of material will get yanked, even if the users still want access and the creators still want them to have that access. Likewise, books (even digital ones) go out-of-print–or worse, fall into a nebulous gray area where they are too valuable to release into the public domain, but to expensive to distribute (link). Still, plenty of copies of those orphan works are still circulating throughout MEL. As for something like Story Corps, it *is* great, but it largely isn’t *here.* Frankly, I’d be overjoyed if the “Story Corps” really *was* like the Peace Corps: An army of peace roaming the countryside and archiving America’s stories. But that’s a big job. It’s best distributed among our nation’s ~9,000 (link) public library systems.

5) HOMELESSNESS AND THE LIBRARY: I can’t speak to this, as I wasn’t at the city council meeting and I haven’t spoken to Ms. Parker about the library in several years. I drafted this column *before* that city council meeting happened–which probably isn’t immediately apparent, since the column came out right after the meeting and coincidentally seems to comment on issues raised at the meeting (some day I’ll write a column about the process that goes into these columns. It’s . . . often fraught).

“THE INDIVIDUAL CITIZEN CAN MAXIMIZE PROFIT BY CHANGING BEHAVIOR.”

I think you mean “utility”, not “profit”, Dave, but it’s probably a common conflation in our money-focused culture.

Good point, Steve. I guess it is a good thing for society that we don’t all gauge our contributions by the personal utility (or monetary) return we derive from them.

Actually, this philosophical point underlies the push for user fees, which appear to be democratic but are the reverse. If we only pay for what we personally benefit from, those who are unable to pay fall off the wagon, and also the community resource can fade away if it is not “profitable”. This goes against my own communitarian ideal.

Michigan’s tax structure has pushed many municipalities and authorities into making as many activities fee-based as possible. This is because the constitutional prohibition on sales taxes, special ticket taxes, etc. (Headlee amendment) make it impossible to have operating funds without either a taxpayer-voted property millage or a fee that can be demonstrated to be related to the service directly provided.

I’m grateful that our library has not succumbed to this trend.