City Planners Preview SEMCOG Forecast

A widely used forecast of population, employment and other community indicators – prepared by the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG) – is being revised through 2040. At a working session on Tuesday, Ann Arbor planning commissioners were briefed on the preliminary results of that work, which will likely be finalized and released in March.

Wendy Rampson, head of planning for the city of Ann Arbor, at the Ann Arbor planning commission's Jan. 10, 2012 working session. Behind her are students from Huron High School, who attended the meeting for a class assignment. (Photo by the writer.)

The forecast is used as a planning tool by local governments and regional organizations, and is updated every five years. A preliminary forecast from 2010-2020 has been distributed to communities in southeast Michigan, including Ann Arbor, to get feedback that will be used in making the final forecast through 2040. At a public forum in Ann Arbor last month, SEMCOG staff also presented an overview from its preliminary 2040 forecast for Washtenaw County.

For the county, the initial forecast shows the population growing from 344,791 in 2010 to 352,616 in 2020 – a 2.2% increase. By 2040, the county’s population is expected to reach 384,735, an increase of about 40,000 people from 2010.

The population in Ann Arbor is projected to stay essentially flat, while some of the county’s townships – including the townships of Augusta, Lima, Manchester, Saline and Superior – are expected to see double-digit growth.

Total employment for the county is expected to grow 20.6% through 2040, from 236,677 jobs in 2010 to 285,659 jobs in 2040. About 50% of all jobs in the county are located in Ann Arbor.

The forecast has implications for policy and planning decisions, including decisions related to transportation funding. For example, the forecast will form the basis for SEMCOG’s 2040 long-range transportation plan, which is expected to be released in June of 2013.

The transportation issue was highlighted during Tuesday’s planning commission meeting. And in a follow-up interview with The Chronicle, Eli Cooper, the city’s transportation program manager, expressed concerns that the forecast might underestimate population and household figures.

Cooper said he’s trying to ensure that SEMCOG has all the data it needs to inform good decision-making. For example, a list of recent and pending developments that SEMCOG is using doesn’t include some major new residential projects, he said, such as The Varsity Ann Arbor. [.pdf of development list used in SEMCOG draft forecast]

This forecast comes in the context of several major transportation projects that are being discussed within the county. That includes a possible countywide transportation system and a potential high-capacity transit corridor in Ann Arbor that would run from Plymouth Road at US-23 through downtown Ann Arbor to State Street and southward to I-94.

The discussion at Tuesday’s working session centered primarily on SEMCOG’s draft forecast for Ann Arbor through 2020. The meeting covered other topics, including an update on the planning staff’s 2012 work plan. This report focuses on the SEMCOG forecast.

SEMCOG Forecast

Wendy Rampson, who oversees planning operations at the city, introduced the SEMCOG forecast by saying that it’s a dry subject, but important – especially for transportation planning. The projections are fairly sophisticated, she said, starting at a macro level by making growth assumptions regionally, then sorting down to the jurisdictional level of counties, cities and townships.

At the same time, SEMCOG forecasters gather data from individual communities, such as site plan reviews for new developments, demolitions, tax assessment figures, and other information. For example, SEMCOG has compiled a list of current and proposed developments, including 33 in Ann Arbor. [.pdf of development list used in SEMCOG draft forecast] All of this data is factored into the forecast model, Rampson said, to derive the best possible projections of changes in population, the number of households, and employment. SEMCOG uses UrbanSim software to develop these forecasts.

SEMCOG Forecast: Employment

The new draft forecast reviewed by the planning commission projects that employment in Ann Arbor will grow 4.5% between 2010 and 2020, from 121,289 jobs in 2010 to 126,783 jobs in 2020. That’s a gain of 5,494 jobs.

However, Rampson said SEMCOG has backed off of its employment growth projections made five years ago for Ann Arbor. The previous employment forecast for Ann Arbor – posted on SEMCOG’s website – is for 134,191 jobs by 2020. The draft revision now projects 126,783 jobs by 2020, or 7,408 fewer jobs than previously forecast.

She said this revision seems reasonable, given the economic climate, but that it concerns Eli Cooper, the city’s transportation program manager, who felt the previous forecasts were already too conservative. Cooper is working with city staff to make sure SEMCOG has all the relevant data to make an accurate forecast, Rampson said, including potential development at the University of Michigan.

Rampson referred to a Dec. 14 email to city staff from SEMCOG lead planner Jeff Nutting, who outlined more details of how the forecast is developed. Nutting specifically described how UM data factors into the forecast:

Land owned by the University of Michigan is tax exempt, so there is not any building or land data contained in the tax assessment files for parcels they own. We obtained from U-M Planning their information on buildings owned or leased by U-M, including square footage, building activity and mail stops. U-M employment, as for all other establishments in the state, is obtained from the State Unemployment Insurance data that all establishments file on a monthly basis, reporting number of employees by location. These employment numbers were broken out to individual buildings owned or leased by U-M using mail stops, a method suggested by U-M Planning.

Of course, U-M has facilities outside the City of Ann Arbor, so not all jobs end up allocated to buildings in the city. The allocation is of course controlled by the number of jobs U-M is actually reporting. In addition, both the city and university master plans were input into the model in the form of future land use and density constraints. Updates to past announcements, such as U-M no longer moving all jobs in leased buildings into the old Pfizer buildings, were also input.

Planning commissioner Erica Briggs asked how accurate the SEMCOG forecasts have been in the past. Fairly accurate, Rampson said, and the forecasts are improving each cycle – although she noted that the forecasts didn’t predict the recent economic downturn. For example, a previous forecast had projected Ann Arbor employment at 125,340 jobs in 2010. Actual employment that year was 121,289 – 4,051 fewer jobs than projected.

Another employment-related factor in the forecast is how Ann Arbor’s job market is changing with respect to the rest of Washtenaw County, Rampson noted. In 2005, 53% of all jobs in Washtenaw County were located in Ann Arbor. That dropped to 51% in 2010, as a higher percentage of new jobs were located outside of the city. The new draft forecast projects a further drop, estimating that by 2020, only 50% of the county’s jobs will be located in Ann Arbor. It’s a change, but not a dramatic decrease, Rampson said. [.pdf of 2020 draft employment forecast for communities in Washtenaw County]

Planning commissioner Diane Giannola clarified with Rampson that the figures for jobs refer only to the actual positions, not to the number of people who both work and live in the county.

SEMCOG Forecast: Population & Households

The number of households in Ann Arbor is expected to grow 3% through 2020, from 47,060 to 48,449 – an increase of 1,389 households. [.pdf of 2020 draft forecast of households in Washtenaw County communities]

Rampson pointed out that while the forecast calls for more households, Ann Arbor’s population is expected to remain stable – growing only 0.4% to 114,367 people by 2020. [.pdf of 2020 draft forecast of population in Washtenaw County communities] What this means, she said, is that more housing units are being added and people are dispersing – the forecast indicates that there will be fewer people per household. The forecast likely reflects a demographic change: More older residents with no children at home, for example, as well as more younger, single residents.

The Dec. 14 email from SEMCOG’s Nutting stated that the new draft forecast of 48,449 Ann Arbor households in 2020 is more households than SEMCOG had previously projected for 2040 in its last forecast. The new forecast indicates more positive assumptions about Ann Arbor’s housing unit growth than SEMCOG analysts had five years ago, he wrote. The city is also expected to have stronger housing growth in the next decade than any other community in Washtenaw County.

Planning commissioner Bonnie Bona asked whether SEMCOG’s model takes into account zoning changes – the fact that the city now allows for greater density with mixed-use zoning. It’s difficult to project how much residential development will ultimately occur on parcels that have mixed-use zoning, Bona said.

Rampson replied that SEMCOG does consider factors like Ann Arbor’s relatively new A2D2 zoning and its downtown plan. She said she would follow-up with SEMCOG and ask how the forecast handles mixed-use zoning specifically.

Erica Briggs asked if her understanding was correct – that developers’ plans to build more housing factors into SEMCOG projections of household growth. Basically, she said, it sounds like if housing is being built, the assumption in the forecast is that those units will be filled. That’s right, Rampson said. And because the population is projected to grow only slightly, the forecast assumes that over time, there will be fewer people living in each unit.

That approach to the forecast seems questionable, Briggs said. It doesn’t address the fact that at some point, the city might simply have too many housing units. Rampson replied by saying she didn’t think the forecast model includes vacancy rates. However, the model does use historic patterns of population migration into and out of the region to make projections at the macro level. The model then disaggregates those projections to the local communities. ”None of this is predictive,” Rampson cautioned. “It’s just a planning tool for us.”

Bona said it would seem to make more sense to calculate job growth, and from that make projections about population, which would then inform housing needs.

Planning commissioner Kirk Westphal noted that University of Michigan students are a factor in population projections. For UM, a change of 1,000 people “is a rounding error,” he joked. [The university's Ann Arbor campus has an enrollment of about 42,000 students.]

Westphal noted that the number of housing units was projected to increase roughly 3.5 times more than the population. He indicated that he didn’t quite know what to make of that aspect of the forecast.

Rampson ventured that more young singles are staying in town after graduating from UM, and likely moving from group housing – like dorms or fraternities and sororities – into single-unit apartments. Eric Mahler, the commission’s chair, said the trend in housing is away from large McMansions and toward smaller units, which might be driving the increase in the number of households in SEMCOG’s forecast.

Planning commissioner Wendy Woods asked about infrastructure for services like municipal sewer and water. As the university grows, there’s less capacity for development elsewhere in the city, she said. Does SEMCOG’s model take that into consideration? Rampson replied that those kind of capacity issues are handled only in a very macro way. For example, the model would factor in whether an area has access to water and sewer, but it would not look at data such as the size of a water main, for example.

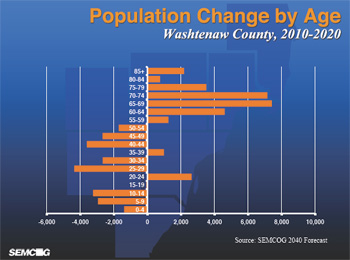

A chart showing SEMCOG's draft forecast of the Washtenaw County population change by age between 2010-2020. This information was presented by SEMCOG staff at a December public forum in Ann Arbor. (Links to larger image)

Woods also queried Eleanore Adenekan, a commissioner who’s also a local real estate agent, asking whether SEMCOG’s forecast for households aligns with what Adenekan sees in the market. “Absolutely,” Adenekan said.

But Rampson questioned some of the underlying data that Nutting cited in his email to city staff. Nutting wrote that SEMCOG’s forecasted growth of households is based in part on 2,000 net housing units that have been added in the city since the beginning of 2010. Rampson said that number seemed high to her. “Eli [Cooper] won’t be happy with me,” she said, “but we’ll have to follow up.”

Briggs noted that SEMCOG’s forecasting model doesn’t seem to jibe with the sustainable community approach that Ann Arbor is trying to create. For example, the most household growth is forecast for the townships, she noted, adding that “it will be interesting to see how that plays out.”

Mahler asked whether data would be available regarding race and age of the city’s population. It would be helpful, for example, to know how many people are in their 20s, or are older than 65, because their needs for services like transportation might differ from the general population. He also wondered if data were available that might predict the size of K-12 school populations.

[A preliminary forecast showing population change by age in Washtenaw County through 2020 was part of a SEMCOG public forum in December, but was not presented at Tuesday's planning commission session. The forecast calls for population gains among all age groups over 55, as well as in age groups from 20-24 years old and 35-39 years old. All other age groups will see population losses, according to the forecast.]

Rampson said she’d follow up with SEMCOG to get more information on how the forecast includes mixed-use development, and whether the forecasting model accommodates the sustainable cities planning concept. She’d also ask for forecast data on school-age population, as well as general age, race and national origin demographics.

SEMCOG Forecast: Transportation

Tony Derezinski, who serves on both the planning commission and city council, had attended an outreach meeting held by SEMCOG in mid-December to discuss the draft forecast. He said that Michael Ford, CEO of the Ann Arbor Transportation Authority, had attended the meeting, too. Ford was extremely interested in the forecast, which has a direct relationship to what AATA is doing, Derezinski said. That’s especially true for population growth in the county’s townships, he said, given that AATA is looking to expand services outside of Ann Arbor.

Eli Cooper, the city’s transportation program manager, also attended the December SEMCOG meeting, Derezinski continued. Rampson noted that Cooper is looking for transportation funding sources for the future. An area’s employment, population and number of households have implications for federal transportation funding. Rampson said that given the economy, it will take time for growth in these areas to return to previous levels, assuming it ever does.

In a follow-up phone conversation with The Chronicle, Cooper elaborated on his concerns with the forecast. He said his concerns are based on an understanding of how these numbers are used by transportation planning agencies, and that he wants to provide SEMCOG with the best possible data to inform good decision-making.

For example, he noted that the list of residential developments used by SEMCOG doesn’t capture everything that’s being planned in the city. [.pdf of development list used in SEMCOG forecast] The Varsity Ann Arbor – a 13-story building at 425 E. Washington with 181 apartments and a total of 415 bedrooms – was recently approved by Ann Arbor city council and will begin construction soon, but it’s not on the list. Nor is the 618 S. Main development, with a proposed 180 apartments, that’s just now moving through the city’s approval process. A request for site plan approval is on the planning commission’s Jan. 19 meeting agenda.

Cooper also questioned whether the draft forecast takes into account the city’s zoning changes made in recent years – including changes in area, height and placement – that would accommodate more residential growth.

The forecast has implications for how investments are made in transportation infrastructure, Cooper said. For example, if SEMCOG forecasts that 15,000 jobs will be added in Ann Arbor through 2040, but the population forecast remains stable, then the city will expect to see an increase of “in-commuting,” Cooper said. And since most commuters use vehicles, that increase will result in traffic congestion and put pressure on the city’s parking system.

However, if the forecast assumes that a portion of those jobs will be held by people who live in Ann Arbor, he said, and that the population will increase as a result of the added employment, then there might be a stronger argument for investing in the Plymouth-State Street transit corridor, or in more frequent bus service within the city.

Cooper said he thought that SEMCOG analysts were open to additional input. He also noted that the Washtenaw Area Transportation Study (WATS) has provided SEMCOG with its own forecast through 2040, which will help inform SEMCOG’s projections. [.xls spreadsheet of WATS forecast through 2040]

For background on local transportation issues, see Chronicle coverage: “AATA OKs Ann Arbor-Ypsilanti Route Increases” and ”Washtenaw Transit Talk in Flux.”

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public bodies like the Ann Arbor planning commission. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

The chart tells me that a lot of those new “households” projected for 2020 are going to be in assisted living and memory care units.

Mr. Cooper seems to have a solution – more, and more expensive, mass transit – in search of a problem that SEMCOG does not think will exist. The idea that transportation planning should hang on whether or not couple of apartment buildings get built seems a tad desperate.

It seems, from the degree of surprise among Ann Arbor city officials that this article documents, that the city has done all its “planning” without ever contacting SEMCOG and consulting its population projections. Apparently, all the zoning changes/infrastructure upgrades were based on little more than “If you build it, they will come”. Or does the city have some other authoritative source of growth – even an internal study – that SEMCOG has overlooked? Surely the city must have other data sources that support the drive to density – even the local ruling class can’t be that amateurish. What is this other data source?