Ann Arbor Budget Process Starts Up

A short meeting of the Ann Arbor city council’s budget committee – just before the full council’s Jan. 22 session – resulted in a consensus on an approach to budget planning for the next two-year cycle.

The Ann Arbor city council is beginning a budget planning process that should culminate in a council vote to adopt a fiscal year 2014 budget at its second meeting in May, which falls this year on May 20, 2013.

City administrator Steve Powers and chief financial officer Tom Crawford sketched out three kinds of topics they could explore with the full council at work sessions through the spring: (1) funding for items in the capital improvements plan (CIP); (2) budget impact analysis, broken down by service unit; and (3) additional resources required to support the city council’s five priority areas, which were identified in a planning session late last year.

The top three priority areas are: (1) city budget and fiscal discipline; (2) public safety; and (3) infrastructure. Two additional areas were drawn from a raft of other possible issues as those to which the council wanted to devote time and energy over the next two years: (4) economic development; and (5) affordable housing.

Possible city council work session dates are the second and fourth Mondays of the month. Regular meetings fall on the first and third Mondays.

The city council will be adopting a final budget for fiscal year 2014 by its second meeting in May. FY 2014 starts on July 1, 2013. Although the council approves an annual budget for the next fiscal year, the city uses a two-year planning cycle. This year starts a new two-year cycle, the first complete one for city administrator Steve Powers, who started the job about a year and a half ago, in September of 2011.

During some back-and-forth with the budget committee about the staff’s ability to provide all the information to the council that the committee had been describing – within the timeframe of the budget season – Powers joked: “Tom and I aren’t rookies!” Powers was previously Marquette County administrator for 16 years. Crawford has served as Ann Arbor’s CFO for more than eight years.

The council’s five-member budget committee consists of: Sabra Briere (Ward 1), Jane Lumm (Ward 2), Christopher Taylor (Ward 3), Marcia Higgins (Ward 4) and Mike Anglin (Ward 5).

An interesting wrinkle that emerged during the budget committee’s discussion was the role to be played by the city council in shaping the capital improvements plan (CIP). In response to some interest expressed by committee members to amend the CIP, Powers encouraged them to think in terms of allocating funds (or not) for elements of the plan. That’s because the content of the CIP is the statutory responsibility of the planning commission, not of the city council. The city council’s role is to determine which projects should be funded, Powers explained. But it’s for the city planning commission to finalize the content of the CIP itself.

This report includes more on the Michigan Planning Enabling Act (Act 33 of 2008) and the city council’s recent history of amending the CIP.

Capital Improvements Plan: 2014-2019

The city’s planning commission has already voted, on Dec. 18, 2012, to approve the CIP for 2104-15. [.pdf of CIP for FY 2014-2019] The CIP is developed and updated each year, looking ahead at a six-year period, to help with financial planning for major projects – permanent infrastructure like buildings, utilities, transportation and parks. It’s intended to reflect the city’s priorities and needs, and serves as a guide to discern what projects are on the horizon.

This year, 377 projects are listed in 13 different asset categories. In the report, new projects are indicated with gray shading. They include renovating and/or remodeling five fire stations, 415 W. Washington site re-use, a park at 721 N. Main, urban park/plaza improvements, several street construction projects, a bike share program, and the design, study and construction of a new rail station.

Capital Improvements Plan: Amending the Plan?

Three years ago, on Feb. 16, 2010, the city council voted to amend the CIP after receiving it from the planning commission. On that occasion, the project that the council removed from the plan was one labeled the “Runway Safety Extension” for the city’s municipal airport.

The possible runway extension has been controversial for a few decades, but re-emerged again as a point of friction more recently in the context of an environmental assessment connected with the runway extension. [The runway extension is included again in this year's CIP.] The city council has voted periodically to fund the project, which taps non-local sources in addition to the smaller amounts needed from the city. The most recent vote by the council on that study came on Aug. 20, 2012.

Again on Feb. 7, 2011 city council amended the CIP to exclude the runway extension. Roger Fraser, who was city administrator at the time, hinted during the council’s meeting that the council was not actually expected to alter the plan itself [emphasis added]:

City administrator Roger Fraser noted that the planning commission is required to propose the CIP, but that not every item in the plan needs to have funding identified. Development of the plan, he said, complies with state law, and technically, the city council should simply be voting to receive the plan – implying that it was not really expected that the council would alter the plan.

Last year, on May 21, 2012, the council received the FY 2013-18 CIP attached to its agenda as a communication, and did not vote on it except to receive it along with several other communications. By that time, Powers had been serving as city administrator for about 9 months. The memo attached to the item on the agenda recited the past practice of amending the CIP, but noted that the city council did not need to act on the CIP [emphasis added]:

Similar to the City’s two-year budget process in which this year’s budget review by City Council consists of adjustments to the second year of the two-year budget presented to Council in the spring of 2011, the CIP approved by the Planning Commission consists of adjustments to the second year of the FY12-17 CIP approved by the Planning Commission on January 4, 2011. On February 7, 2011 City Council approved the FY12-17 CIP as the basis for the City’s capital budget, with the exception of the Airport Runway Safety Extension Project which was removed from the FY12 Capital Budget. As the adjustments to the CIP and to the capital budget under review by the Council were performed jointly, and with approval of the adjusted capital budget to be performed by Council following its review of the adjustments, no action regarding the CIP is required by City Council.

When Powers sketched out the overall concept for budget planning at the Jan. 22 meeting of the city council’s budget committee, Jane Lumm (Ward 2) expressed an interest in amending the CIP. She noted that when she’d served on the council in the mid-1990s, she recalled undertaking amendments to the CIP. And Sabra Briere (Ward 1) recalled the more recent amendments of the CIP with respect to the airport runway.

Powers responded by pointing out that the CIP was not the purview of the governing body – in this case, the city council – but rather of the planning commission. What the council was responsible for, Powers explained, was allocating funds (or not) for the projects in the CIP. Powers alluded to the relatively recent change in the statute that lays out the responsibilities of the city planning commission. He confirmed later for The Chronicle that he was referring to the Michigan Planning Enabling Act 33 of 2008, which reads in relevant part:

125.3865 Capital improvements program of public structures and improvements; preparation; basis.

Sec. 65. (1) To further the desirable future development of the local unit of government under the master plan, a planning commission, after adoption of a master plan, shall annually prepare a capital improvements program of public structures and improvements, unless the planning commission is exempted from this requirement by charter or otherwise. If the planning commission is exempted, the legislative body either shall prepare and adopt a capital improvements program, separate from or as a part of the annual budget, or shall delegate the preparation of the capital improvements program to the chief elected official or a nonelected administrative official, subject to final approval by the legislative body. The capital improvements program shall show those public structures and improvements, in the general order of their priority, that in the commission’s judgment will be needed or desirable and can be undertaken within the ensuing 6-year period. The capital improvements program shall be based upon the requirements of the local unit of government for all types of public structures and improvements. Consequently, each agency or department of the local unit of government with authority for public structures or improvements shall upon request furnish the planning commission with lists, plans, and estimates of time and cost of those public structures and improvements.

In the case of Ann Arbor, there’s no exemption of the planning commission from having responsibility for the CIP.

At the committee meeting, Briere observed that – from her perspective as the recently appointed city council member to the planning commission – she perceived that planning commissioners viewed the CIP as a document that could be altered by the city council, and thus commissioners viewed it in some sense as merely a recommendation by the commission. She ventured that Powers’ explanation of the respective roles of the planning commission (which is responsible for the content of the plan) and the council (which is responsible for the budgeting of specific projects in the plan) would need to be incorporated into the planning commission’s culture.

Water Mains in the CIP

At the budget committee meeting, Lumm indicated that her interest in amending the CIP stemmed from a desire to see a water main replacement project in her ward be funded for 2014 instead of 2015. And in the course of deliberations during the city council session that followed the budget committee meeting, Lumm’s Ward 2 council colleague Sally Petersen mentioned a water main replacement project she wanted the city to undertake. The two councilmembers confirmed for The Chronicle that the specific water main project they meant was on Yellowstone, which is in the eastern area of the city, bounded by the east-west portion of Green Road on the north, and Bluett Road on the south.

The CIP for FY 2014-19 includes the Yellowstone water main replacement for 2015, and indicates a cost of $650,000. The CIP includes more than 30 different water main projects citywide. Projects are ranked on a priority scale with a number of factor weights. Lumm wants to see the Yellowstone moved a year earlier – to 2014. She responded to a query from The Chronicle by indicating that the Yellowstone water main has had six breaks in a five-month period.

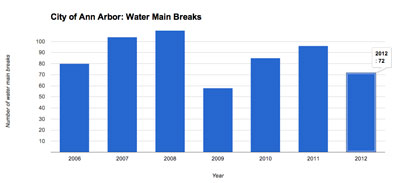

Based on data compiled by The Chronicle from the city’s comprehensive annual financial reports (CAFRs), total water main breaks citywide in the last four years are less frequent per year than in the previous three. In 2012 there were 72 water main breaks citywide.

City of Ann Arbor water main breaks: 2006-2012. Data from city of Ann Arbor comprehensive annual financial reports.

The Chronicle could not survive without regular voluntary subscriptions to support our coverage of public bodies like the Ann Arbor city council. Click this link for details: Subscribe to The Chronicle. And if you’re already supporting us, please encourage your friends, neighbors and colleagues to help support The Chronicle, too!

I found it odd that the City Administrator suggested that the full Council might want to discuss the “additional resources required to support the city council’s five priority areas”. If you budget by priorities, then the top priorities get the first available resources and should not require “additional resources”. Any additional resources available should be held in reserve or used on things that are less necessary than your top priorities.

Unfortunately, the City does not use a priority based budgeting method, such as zero-based budgeting. Instead, the City starts each budget by tinkering with the prior budget. The act of increasing funding in one area requires new revenue or cuts to another area.

Under the City’s current method, the bureaucratic struggle to maintain budgets prevails over a common sense ordering of priorities. Rather than requiring an affirmative finding of need to justify each spending decision, one must create an argument to justify cuts.

If the City listed its spending priorities in order it could fund each one working down the list from most important to least important. The final budget would fund those items that had been deemed more important than the things that could not be afforded. This isn’t a complex concept and is not a difficult process. It does take some discipline and some candor about what the City sees as its priorities. It is the most responsible way to budget scarce resources.

The question of priorities is complex. We often debated this when I was on the Board of Commissioners. While the process recommended by Jack Eaton seems sensible, it isn’t workable in practice, because some items that may not seem top priorities are still necessary and important at some level, and very important to certain sectors. An example is the debate this last year over the Humane Society funding at the county level. Barbara Bergman often expressed the view that she would not fund doggies at any level as long as there was one hungry child. (This is paraphrased from memory, please correct at will.) Under that plan, there would be no funding for doggies at all, because it would be hard to imagine completely eradicating hunger.

Perhaps a better approach is to identify discretionary items and items deemed to have either statutory (including restricted funds, etc.) or high community priority. So we have a high community priority for public safety. Much money for parks is from dedicated millages, and parks are also a high community priority. Those are easy. Identifying the discretionary items is the tricky part.

Correction to Vivienne Armentrout’s quote: it was I who said, “As long as one child in Washtenaw County goes to bed hungry I am not much interested in dogs”. This quote (which was published in the Chronicle and later reprinted in The Ann) was said in frustration at having to allocate more money than I though necessary for the mandated service the County is required to provide – that is, picking up stray dogs. I was very dissatisfied with the information provided to the Board of Commissioners by the Humane Society of Huron Valley – they came up with a price per dog, but they never addressed the actual NUMBER of stray dogs, as opposed to owned dogs. In the end I voted in favor of a directive to the County Administrator to come up with a contract, which she has done. Commissioner Bergman also voted in favor of this directive as well, thus contradicting the view attributed to her above, that she would not, under any circumstances, vote for such funding.

Nevertheless, in my world, children’s hunger is MUCH more important than the welfare of animals. And being dismissive by saying that “it would be hard to imagine completely eradicating hunger” shows a lack of both imagination and compassion. I am talking about Washtenaw County, not the world! It can, and should, be done here.

Thanks for the correction. I didn’t take time to look up the quote. (Belatedly, I did find a Bergman quote, but it was different – sorry to conflate the two.) The BOC had a tough job with this, resolved as far as I can tell in a fair way. I was using the issue as an example of how absolute priorities work, not in order to comment on the specifics. I certainly support the efforts here and elsewhere to eradicate child hunger (applause here to the miraculous Food Gatherers) but I suspect that we could put infinite resources into that and other human needs. If we suspend all other governmental functions until one need (whether it is public safety or child hunger) is fully addressed, others may not be addressed at all. The reason is that more funding can always be useful to any one program, and especially in these times, we are not likely to attain the most desirable level for that one program. Show me a program manager who will say, “no thanks, doing fine – can’t use any more money to make my program even better”.

The very difficult job of elected officials in budget deliberations is to sort out the different types of needs and allocate funding to each. This is likely to be a qualitative judgment rather than a quantifiable measure like a priority rating.

Re (2) Vivienne, I don’t think the task of assigning relative priorities is as difficult as you contend. It is my understanding that many complex organizations use zero based budgeting. Every organization has its mandatory expenditures — FICA contributions, Workers’ Compensation insurance premiums, costs of compliance with various governmental regulations, etc. Such mandatory expenses are obviously high priority items in a budget.

While we broadly identify public safety as a high priority, that area is not limited to the cost of personnel. We need to equip, train and support that staff. So within the safety category, you would need to pay for the buildings, utilities and maintenance required by those departments.

Your observation that some City revenues are restricted seems to resort to the former City Administrator’s imagery of budgetary buckets. Even recognizing that the total budget has restricted sub-budgets, does not reduce the need for priorities in the whole budget as well as within those restricted budgets. Parks has a restricted millage and receives general funds (supposedly in the same proportion to the whole general fund as existed when the parks millage passed). Within that parks budget there is a need to set priorities to get the most out of our resources.

While the general sense of priorities must be identified by the governing body,the actual burden of forming a priority based budget would still fall on our professional staff. If the Council guides the staff by setting priorities, the budget fight will not be a decision between animal control or human services. The budget likely includes spending that is less important than both of those services.

The purpose of setting priorities is to avoid leaving needed improvements to public safety as an afterthought in a general fund budget of about $79 million. A decision on how to spend the last available million should be between relatively low priority items.