Near North Nears Next Review

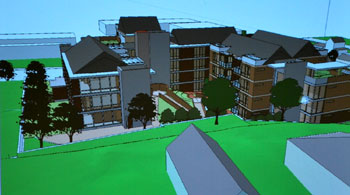

Damian Farrell, architect for Near North. Farrell rotated and panned across the proposed building from various angles to show neighbors the current state of the design.

The gathering on Wednesday evening at the Ann Arbor Community Center to discuss a proposed affordable housing development had been publicized as a 2-hour long “community design charrette.” But the 35 or more immediate neighbors and other interested parties who attended the meeting filled a bit more than the first hour asking questions that addressed the topic of the developer’s motives, the projects’ consistency with the mission of the non-profit partner on the proposal (Avalon Housing) and the conformance of the project to the city’s various planning documents.

Architect Damian Farrell was eventually given the chance to project live images from his design software onto the wall, and manipulate them to illustrate changes that had been made as a result of the previous two charrettes. But the ensuing conversation on design elements was also interspersed with concerns about topics from the first hour.

Two and a half hours into the meeting, a man stood and said: “I am homeless.” He’d heard people pick at the project, he said, but he hadn’t heard anyone ask this question about it: “What can we do to help?” It was more than three and a half hours after the meeting started when the last of the post-charrette conversational pods headed out the door.

By Jan. 21, the project team hopes to be able to submit responses to any of the city planning staff’s concerns expressed after the project’s initial review, which began after the project was submitted in December. Near North could come before the city’s planning commission as early as Feb. 19.

Background on Near North

At the meeting Wednesday, Bill Godfrey of Three Oaks Group explained how the acquisition of the land along the east side Main Street between Summit and Kingsley had begun in 2003. The initial proposal for the affordable housing project was for 67 units, in a 6-7 story building with around 64,000 square feet. That had been reduced to 38 units, in a 3-4 story building comprising around 45,000 square feet. The building would replace several existing houses along the street.

Between the second charette and Wednesday’s gathering, the main changes in design were the elimination of a driveway entrance onto Main Street on the south end of the site, as well as the reconfiguration of an entrance on that end of the building. The sequence of images below, which reflects the status of the design as of Jan. 14, begins at the southwest corner of the proposed project and circles it counter clockwise.

Southwest corner of building. View is to the east. The pinkish pathway from the sidewalk replaced what was a driveway entrance on a previous design iteration. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Back of the project seen from the Fourth Avenue side. View is to the west. (Image links to higher resolution file.)

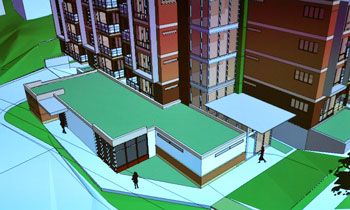

Northwest corner of project. View to the southeast. The one-story element is envisioned as non-residential, that is, retail or office). (Image links to higher resolution file.)

Avalon Housing Mission

Michael Appel, executive director of Avalon Housing, Inc, made introductory remarks at the meeting to illustrate the contrast between this project and “other projects using the same language we’re using.” By “the same language” was meant partly “affordable housing” defined in terms of area median income levels. Near North, Appel said, would specify in the language of the alternate zoning (PUD) being requested that 100% of the units would affordable, capped at a rental rate corresponding to 50% of AMI. That translates to an annual income of roughly $33,000 for a household of two or $29,000 for a household of one. The maximum rent (including utilities) that could be charged would be about $770.

Further, out of the 38 units, 14 would would be reserved for “supportive housing,” which Appel characterized as targeted for people making less than $15,000 a year. This was not, emphasized Appel, “disguised student housing.”

Later in the Wednesday meeting, Sonia Schmerl (former member of the city’s historic district commission and former candidate for city council in Ward 5) would point out that city council ultimately had a role to play with respect to the affordable housing component. Namely, they decide whether the public benefit of a PUD proposal (which is a requirement) was sufficient for approval. And, whereas with other projects it was possible to debate whether a claimed public benefit was actually a benefit, in this case, Schmerl said, there was no question that the affordable housing component of Near North was a public benefit.

[Editor's note: By way of contrast, the City Place PUD proposal, recently defeated by a unanimous vote by city council, offered 15% of its units at a rate corresponding to 80% of AMI. The developer had indicated a willingness to make an additional 38 units (out of a total of 90) available at the 90% AMI threshold. At least four councilmembers appeared to indicate a willingness to vote yes on City Place, if the additional units at the 90% had been written into the development agreement.]

In response to Appel’s introductory remarks and his display of a map showing the distribution of affordable housing units in the Ann Arbor area, some attendees expressed an interest in having copies of the map. [Editor's note: The image available under that map is taken from a photograph of the physical map, and is a suitable resolution for on-screen viewing.]

Attendees elicited from Appel what the definition of a “unit” was. Answer: whatever space it is the tenant leases. Of the 210 units managed by Avalon, said Appel, almost all of the units were apartments, as opposed to bedrooms.

They also wanted to know how the 24 units of entry-level workforce housing (those capped at 50% AMI) fit in with Avalon’s mission, which had historically focused on supportive housing for single adults. Appel spoke of expanding their mission to include the broader effort to establish more affordable housing options – a need that existed in the community. One attendee asked point blank: “Was Avalon looking for a project like this?” Appel responded by saying that the proposal by Three Oaks Group “did not provoke the discussion” of an expanded mission – it was a conversation that had already begun.

Bill Godfrey, of Three Oaks Group, holds the map showing the distribution of affordable housing units in the Ann Arbor area, as Michael Appel, of Avalon Housing, discusses it.

Avalon would be the property manager of the housing if it is built. In response a query about what being the property manager means, Appel said that it meant that Avalon would screen the tenants, handle leasing, perform maintenance, and ensure income requirements were met.

People also made a connection between the tax-credit financing proposed for Near North and the same kind of financing that many of them had heard in connection with another proposal – the “100-units proposal” – and wanted to know how this project would be different. The model for the 100-units proposal, Appel said, was a front-desk security model, with office space for a dedicated on-site case worker, neither of which would be featured in Near North.

One attendee noted that one of the attributes cited as a positive for other Avalon housing was that they were not readily identifiable as Avalon houses, because they blended in with the neighborhood. That attendee wondered if the scale of this project was consistent with that notion. Appel pointed out that other multiple-family projects currently managed by Avalon included complexes with 23, 30, and 39 units. Further, he said, Avalon would be taking over complexes of 48, 43, and 23 units as a result of their merger with the Washtenaw Affordable Housing Corporation (WAHC).

“Why not rehab the existing homes as affordable housing?” some people wanted to know. Appel explained that use of single-family homes was not a typical strategy they used, citing the challenges associated with structures used in ways they had not been built for originally.

Developer Motive

Much of the interaction between Godfrey of Three Oaks Group and the neighbors was centered around Three Oaks’ motive, in the context of land acquisition made at the peak of a real estate market. Godfrey, said many in attendance, had paid too much for the properties where the project was proposed to be built, and the partnership with Avalon Housing to build affordable housing was just a “vehicle” to extract himself from a financially difficult situation. For his part, Godfrey acknowledged that for some of the properties they had purchased later, they had paid inflated prices, as a function of people recognizing that Three Oaks Group was trying to accumulate a large parcel. One example he gave was a house for which they’d paid $300,000 that was only worth $250,000. He said they would be lucky to break even at the conclusion of the initial 15-year tax-credit financing period.

One attendee observed that if a private party had purchased a house for more than it was worth, the owner would be forced to simply sell at a loss. Godfrey responded by asking why Three Oaks should not be able to take advantage of financing opportunities that were available (in the tax-credit financing market).

After much discussion of the financing, and whether the developer was pursuing an affordable housing option for financial reasons, one attendee said flatly that he needed more convincing that Godfrey actually wanted to build affordable housing, as opposed to it being a matter of financial convenience, in order to win his support.

Godfrey responded by saying that this project did not reflect a new interest in affordable housing, but rather a long-term concern about the issue, citing his service several years ago on the local advisory board of the Local Initiative Support Corporation (LISC) – where he first met Appel.

Peter Pollack, an architect who attended the meeting as a neighbor – he’s not working on the project professionally – objected to discussion of what people believed the developer’s motive might be and rejected that line of thinking as narrow and unproductive. Pollack said that he had problems with some of the design features, but that they should focus on the challenge of whether the proposed design could be modified in a way that made it sufficiently integrated into the visual patterns and rhythms of the prevailing architecture of the neighborhood to win support from the community.

Master Planning and Project Design

The current name of the project is Near North, which on Wednesday Godfrey said reflected input from the previous neighborhood meetings. The theme of “near” versus “in” is one that has arisen with some frequency in the discussions of recently proposed projects in the context of the city’s master plans. Ray Detter, who chairs the Downtown Area Citizens Advisory Council, has – at any number of public meetings covered by The Chronicle recently – stressed the importance of the distinction that the Central Area Plan makes between “in downtown” and those residential areas “near downtown.” Typically Detter has made this point with respect to the higher density called for by the Central Area Plan in the downtown (i.e., the Downtown Development Authority area) as contrasted with the preservation of neighborhoods that are in the central area, but outside of downtown. Near North is (well) outside the DDA boundaries but in the Central Area.

On single-sheet copies that Detter made available at Wednesday’s meeting was a bulleted list of those recommendations of the Central Area Plan that deal with scale and character:

- To protect, preserve, and enhance the character, scale and integrity of existing housing and establish residential areas, recognizing the distinctive qualities of each neighborhood.

- To encourage the development of new architecture, and modifications to existing architecture, that complements the scale and character of the neighborhood.

- To ensure that new infill development is consistent with scale and character of existing neighborhoods, both commercial and residential.

- To protect housing stock from demolition or conversion to business use and to retain the residential character of established, sometimes fragile, neighborhoods adjacent to commercial or institutional uses.

- To encourage the construction of buildings whose scale and detailing is appropriate to their surroundings.

- To encourage the preservation, restoration or rehabilitation of historically and culturally significant properties, as well as contributing or complementary structures, streetscapes, groups of buildings, and neighborhoods.

- To preserve the historic character of Ann Arbor’s central area.

- Where new buildings are desirable, the character of historic buildings, neighborhoods and streetscapes should be respectfully considered so that new buildings will complement the historic, architectural and internal character of the neighborhood.

- To promote compatible development of sites now vacant, underutilized or uninviting, wherever this would help achieve the plan’s overall goals.

Detter highlighted many of these points in expressing his concerns about Near North. He worried about the precedent this project would set. In response, architect Damian Farrell said that he found it very difficult for anyone to construct an argument for precedent based on a PUD, because by definition a PUD was inherently specific to a particular site, and could not be applied to other situations. Pollack, though, suggested that a precedent might be set with respect to the acceptability of the tearing down of houses.

At one point Godfrey pointed out that part of the point of the meeting was to get a sense of how big a scale would be acceptable to the community, and asked, “What would be an acceptable scale?” Detter’s reply was that he’d like to see the existing houses rehabbed.

At another point, Godfrey suggested, “Buy the houses from us and do it!” Someone quickly inquired about the asking price. “Send me an email, and I’ll give you an answer,” answered Godfrey.

Peak roofs on the building provided an opportunity for people to pun in two senses of the word “pitch.” The word play: (i) when the project was first pitched (proposed) (ii) any one of the isolated design elements could be pitched (eliminated).

Peak roofs were part of the design effort to integrate the architecture of the new building into the existing pattern of free-standing houses. The tension for people in the audience was between mirroring the peak roofs of the surrounding houses, and the increased height they represented. One woman said it was the four-story versus two-story issue that mainly bothered her. Working on the fly, Farrell made the peaks disappear with his software, replacing them onscreen with flat roofs for people to compare.

Pollack weighed in for increasing the proposed setback off Main Street. One member of the audience differed with him, suggesting that a zero setback would mirror the zero setbacks for some of the buildings on the west side of the street.

Stu: “I’m homeless”

Well into the third hour of the meeting, a man named Stu stood and said, “I’m homeless.” He related how he had a job and that he was going to school. [Later he'd tell The Chronicle that it was a GED program at Washtenaw Community College in preparation eventually to become a medical examiner.] He said he’d listened to the attendees pick at the project and pick apart the building, but that he had not heard anyone ask, “What can we do to help?” He related how he’d worked with the police task force distributing blankets to people who live outside, and said that there was a need for the kind of housing that the project offered. He said that he slept in a sleeping bag on the floor of a commercial building.

John Hilton (editor of The Ann Arbor Observer, and who lives in the neighborhood where the project is proposed) had been one of the voices earlier who’d wondered whether the developer’s interest in developing the project stemmed from having paid too much for the property he acquired. He asked Stu if he was aware that many of the units in the project were for people making $33,000 a year, and followed up with: “Do you know many people who are earning $33,000 a year who are homeless?” Stu’s answer: Yes. He went on to describe a family he knew who lived under a bridge.

Yolanda Whiten, director of the Ann Arbor Community Center (where the meeting was held), then weighed in by saying, “I just want to support what he just said.” She suggested that we don’t really understand who the homeless actually are. She described a mother who works at the University of Michigan, a father who works as a chef at a fraternity house, who together made more than $33,000 a year (but less than $40,000) but were “practically homeless,” living in a place where every utility bill was in “shut-off status.” Whiten concluded: “I want to say, ‘Hats off to Three Oaks and Avalon!’”

In response to Stu and Whiten’s remarks, some attendees emphasized that they were for the project, and that they just wanted to make it the best possible project. Hilton said to Stu: “Thank you for the reminder of how important this issue is.”

Nice summary, Dave. Thanks for the thorough coverage. One thing to add about the $33K income level discussion is that all of the units would be 1 bedroom and the typical tenant would be a single person. The examples that Stu and Yolanda gave involved families struggling on that income level. That there is a desperate & huge need for supportive and below-market rate housing is not in question. However, the planning process exists to be sure that structures and their uses are consistent with the long-term growth plans for neighborhoods. If Stu personally knew some of these neighbors – he might appreciate that they have spent their lifetimes and much of their energy assisting others in distress – including offering their own homes to house people in need. In addition, the North Central Property Owners Association (NCPOA) has a record of support for development in the neighborhood. This is the only project that we’ve ever voiced serious opposition to. Hopefully, we will be able to continue to work with the developer to get to a project that we can support.

Also, when Bill Godfrey asked what density would be acceptable, audience members did reply as we have at previous meetings and in writing in response to previous plans. We suggest 20 units & 3 stories with a FAR called for in the exisitng zoning. This project as currently proposed, while lower in units (but not FAR) from earlier versions, greatly exceeds all of those limits.

Thanks for a careful and accurate report. As “Neighbor” notes, NCPOA actively supports redevelopment in our area. Since Letty Wickliffe (may she rest in peace) drafted me into the group in 1981, we’ve helped win approval for about 30 condo and rental units and the 201 Depot office building. In that same period we’ve opposed just one project: 3 Oaks’ first version of this building, four years ago.

That plan was for market-rate condos, not affordable housing, but physically it was identical to the first iteration of “Near North”: it would have had more than 60,000 square feet of floor space, THREE TIME the size permitted under the current zoning. The Central Area Plan calls for even lower density–it envisions one- or two-family units there.

The condos would have overwhelmed the neighborhood, and we told 3 Oaks that we would fight them if they took the plan into planning. They backed off then, and we hoped they would return with a project that we could support. Instead, they returned with the same project but a new partner, Avalon Housing.

As several of us stressed at earlier meetings, we admire Avalon’s work, and appreciate them as a neighbor–they already own two well-managed houses on that same block. But Avalon’s involvement doesn’t change the fact that 3 Oaks still wants to put a downtown building in a residential area. As you note, the current building is about 1/3 smaller than the first version–but so is the lot 3 Oaks is proposing to sell.

That’s the issue I and others were trying to get at with our questions about what 3 Oaks paid for the property. We must not have done a very good job, since two people I admire–Peter Pollack and Sandi Smith–spoke up to say that we shouldn’t question 3 Oaks’ motives.

For me, the question is not whether 3 Oaks sincerely wants to build affordable housing–the question is why it can’t building housing, at any price, that respects the existing neighborhood.

It sounds like questioning the developer’s motives is really NIMBY code for “we don’t want those people here”.

NCPOA didn’t oppose the original condo project because we didn’t want “those people” as neighbors–we opposed it because it was too big. As a neighbor said at the meeting, many of us would like to see this version work precisely because Avalon is involved.