The Battle of Ann Arbor: June 16-20, 1969

June 17, 1969: Officers confer as the crowd swarms on to South University. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

Ann Arbor, like many college towns, is usually a quiet place during the summer months. Most of the students are away on break, the university goes into hibernation, and a calm descends upon the city as residents sit back to enjoy a few months of peace and quiet.

During the turbulent 1960s the summer break was even more eagerly anticipated, offering as it did a brief respite from the regular succession of student-led sit-ins, protests, demonstrations, and strikes that occupied the fall and winter months. But the influx of large numbers of non-student “street people” (i.e., hippie youths) in the closing years of the decade made those last few summers of the ’60s decidedly less peaceful.

Forty years ago this week, the normally sleepy summertime streets of Ann Arbor were violently awoken by a series of violent and occasionally bloody clashes between police and a motley crowd of hippies, radicals, teenagers, university students, and town rowdies. Ostensibly at issue was the creation of a pedestrian mall, or “people’s park,” on South University Avenue – a four-block shopping district adjacent to the University of Michigan campus that caters primarily to a student clientele.

Even in those “interesting” times, the violence in Ann Arbor attracted national attention – including that of J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI. After the fighting was over, the national press lost interest and moved on to other, juicier topics. But on the local scene the repercussions of that summer would reverberate for years after.

The Detroit Free Press would refer to the four nights of conflict as “The Battle of Ann Arbor.”

The First Night

The existence of many widely-varying accounts makes it difficult to determine exactly what transpired during the disturbances. It seems that it all started at about 10 p.m. on Monday, June 16, when a uniformed Ann Arbor police officer attempted to ticket a motorcyclist for doing wheelies in the street. According to a report published by the White Panther Party, a locally-headquartered anti-establishmentarian organization, within a short time a group of around 50 street people gathered and began to quarrel with the officer, who called for backup. By the time the additional four patrol cars arrived, the increasingly hostile crowd had grown to nearly three hundred. The officers withdrew without ticketing the cyclist.

Exultant in their apparent triumph over the police, the crowd decided to hold a spontaneous “liberation party” in the street. A block of South University Avenue was barricaded by parked cars, garbage cans, tires, wooden planks, and other items ready at hand. The crowd, by this time swelled to anywhere from five hundred to a thousand, proceeded to enjoy several hours of dancing, drinking, fireworks, and motorcycle stunts. (One imagines that there was a certain amount of marijuana being smoked, as well.)

The Ann Arbor News reported that at some point during the evening a couple had engaged in “sexual relations…on the pavement of South University, surrounded by cheering young men and women.” Other newspapers also reported the event. The Washington Post stated that “at least one couple had performed the sex act in the street.” The Chicago Tribune went one better, reporting “two lewd acts in the street.” Interestingly, the UM student-run Michigan Daily, a paper not generally known for its modesty, does not appear to have reported “at least one overt sexual act” until more than two months later.

Damages resulting from the festivities were surprisingly minimal. A few slogans were painted on parking signs and windows, and one or possibly two windows were broken. Even more surprising, after the party broke up at around 1 a.m., a number of youths returned with brooms to sweep up debris from the street.

Shadow Police Presence

On this first night, a few plainclothes city police officers were sent to the South University area as observers. They made no attempt to interfere with the revelers, mainly because, as Detective Lieutenant Eugene Staudenmaeir told The Michigan Daily, police intervention would have caused an “instant riot.”

However, Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter Krasny did request that the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Department and the Michigan State Police post in nearby Ypsilanti send additional officers on a standby basis. None of these were deployed on the evening of June 16. Two days later, The Daily would quote Krasny as stating that no police action was taken that first night because of “limited manpower.”

People’s Park

Almost exactly one month earlier, in Berkeley, California, attempts by an assorted group of radicals and hippies to turn a vacant lot into a communal garden and living space – dubbed People’s Park – were ruthlessly crushed with lethal force on the orders of Governor Ronald Reagan.

The events in Berkeley sent shock waves through the American Left, and were undoubtedly still fresh in the minds of many Ann Arbor radicals, including the White Panthers, who early on Tuesday issued a statement calling for the transformation of the South University shopping area into a pedestrian mall, or people’s park. Their choice of names was undoubtedly deliberate and intended to rouse local radicals to action by associating the events in Ann Arbor with those in Berkeley. The allusion worked so well (at least at first) that The Detroit News would claim that activists from Berkeley were behind the Ann Arbor disturbances.

Although a large proportion of Ann Arbor’s anti-authoritarians were in full agreement with the demand, some felt that it was an attempt to infuse a simple display of public merrymaking with a revolutionary significance that was simply not there. Student editorialists for The Michigan Daily asserted that “to most of the celebrants, the take-over was an act of care-free rebellion, not a means to obtain power, appropriate property, or even induce reform.”

The fact that police did not intervene on Monday night tends to add weight to the argument that local radical elements were – at least to some extent – attempting to manufacture an issue of contention between law enforcement and the countercultural community. There were also few, if any, substantive comparisons to be made between the events in Berkeley of a month earlier and the Monday night street party.

The Second Night

Many in the crowd on Monday night and early Tuesday morning were heard to say that they would attempt to hold another street party in the same place the next evening. As the day wore on rumors began to spread that something heavy would be going down in Ann Arbor on Tuesday night. The prospect of a street battle between hippies and police attracted people from all over Southeast Michigan to the South University area. Some came out of morbid curiosity. Others hoped for a chance to strike a blow at “the man.” Reporters and photographers from the Detroit papers and some farther afield descended upon the city, hoping to witness something newsworthy.

None would go away disappointed – although some would have reason to regret their presence on South University that evening.

Word of the impending gathering quickly reached the ears of police. According to The Ann Arbor News, a group of high-ranking law-enforcement officials, including Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey, Ann Arbor Police Chief Walter Krasny, and Prosecuting Attorney William Delhey, spent Tuesday afternoon “laying plans for a show of force if the ‘street liberations’” were to occur again. The police perspective was neatly summed up in a statement later made by Krasny: “We are going to control the streets of Ann Arbor and not give it to a bunch of people who think they own it.” City and university officials were apparently informed of the planned police actions well before the fact.

By the early evening of Tuesday, June 17, the South University area began to fill with people, many of whom were obviously gawkers attracted by expectations of violence. A force of nearly two hundred city police officers and county sheriff’s deputies had assembled at the east end of South University, near Washtenaw Avenue. Over a hundred additional officers were on their way, mostly from nearby agencies but some from as far away as Oakland County.

Minor confrontations between police and the crowd began around 8 p.m. By this time the gathered throng had swelled to over a thousand, with some estimates going as high as twenty-five hundred. Barricades were once again being erected, and many people were dancing and milling about in the street, blocking traffic. At around 9 p.m. Deputy Police Chief Harold Olson used a bullhorn to order the crowd to disperse. When that elicited little or no response, Olson instructed the riot-equipped officers to advance and clear the street.

As the wave of lawmen swept westward down South University, most of the crowd retreated, but some began to hurl rocks, bricks, and bottles. Sheriff Harvey ordered repeated blasts of tear gas fired into the area, apparently on discovering that projectiles were being thrown from rooftops.

In this first sweep it took about an hour for police to clear the street. Twenty-five people were arrested. After this, groups of officers moved about the area using night sticks and rifle butts to urge pedestrians to keep moving. The Michigan Daily reported that at two different times small contingents of police charged some distance into the UM campus to break up groups of students who had gathered there, at least once using smoke or gas. Some of the students who were set upon by officers claimed to have been simply leaving the library after an evening of study.

After the initial sweep the South University area remained relatively quiet until about midnight, when a crowd began to gather near to University of Michigan President Robben Fleming’s house. Fleming had emerged from his home some time earlier to try to mediate between the crowd and police. While Fleming was engaged in dialogue with the crowd, a passing contingent of officers launched a smoke bomb into the area, apparently without provocation.

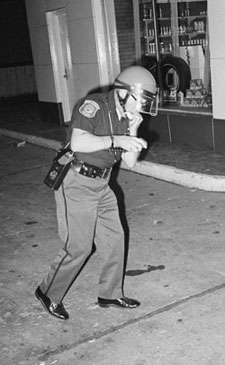

June 17, 1969: An injured officer after having been hit by a projectile. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

The crowd near Fleming’s house soon swelled to around eight hundred. Police drew up shoulder-to-shoulder in battle formation to the east of where the youths were massing. Fleming spoke with Sheriff Harvey, urging restraint. Harvey made no effort to disguise his contempt for the president’s advice, reportedly calling Fleming a “smart ass.” Deputy Chief Olson, however, granted the president a few minutes to try to disperse the crowd peacefully. But when an officer was hit by a thrown brick, Harvey and Olson ordered their men to advance and “clear them out.”

Once again South University was engulfed in a conflict that would not have seemed out of place on a Stone Age battlefield – one side swinging clubs and the other hurling rocks. The retreating crowd soon broke into smaller groups that police chased down side streets. More tear gas was fired into the area, and an additional twenty-odd arrests were made.

It was all over by 2 a.m. In total, nearly 50 people had been arrested, about half of whom were charged with “contention in the street,” a misdemeanor. The other half were charged with violating Michigan’s new riot statute, put in place following the Detroit race riots of 1967. “Inciting a riot” was a felony punishable by up to ten years in prison and/or a fine of up to $10,000.

Not Chicago All Over Again – But Worse than Detroit

Shortly after the conclusion of Tuesday night’s fracas President Fleming issued a statement that was generally supportive of police actions but criticized of the use of tear gas, saying that “it tended to excite the crowd perhaps more than it helped.” Otherwise, he felt that “the police exercised remarkable restraint.”

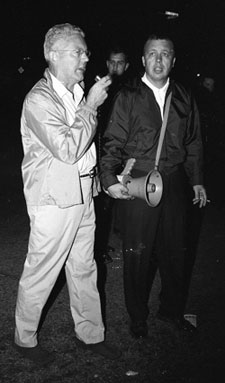

June 17, 1969: University President Robben Fleming confers with Deputy Chief of Police Harold Olson. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

Ann Arbor Mayor Robert Harris was even more supportive of the constabulary, at least in his initial statements. In an open letter to the university community, he attempted to defuse anger at the police. “The sad events of last night were not a ‘police riot,’” he wrote. “They were not Chicago all over again.” Harris was referring to the infamous confrontations between police and demonstrators in the streets of Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Detroit News photographer James Hubbard disagreed with Harris’s assessment. Hubbard was present for most of the Tuesday night conflict, and condemned police conduct as “shocking and unbelievable,” saying by way of comparison, “I spent eighty hours on the streets during the 1967 Detroit riots and I never saw police behave that way.” Hubbard reported that he was clubbed several times on the legs and back, as were many other reporters and photographers. During the final sweep of South University Hubbard “saw 15 to 20 cops chasing one guy. One knocked the guy down and others ran up and began clubbing and kicking him.”

It must be noted, however, that for their part the demonstrators were not entirely innocent of violence. Fifteen police officers were reported to have been injured by projectiles, and some newsmen reported being hit with rocks thrown from the crowd. Deputy Chief Olson was struck in the chest and groin with rocks, and Sheriff Harvey suffered cuts from broken glass. At one point a number of incendiary devices – variously described as cherry bombs, fire bombs, or (improbably) Molotov cocktails – were launched at police, with one officer receiving a serious leg injury as a result. A seventeen-year old boy was also arrested and charged with felonious assault after allegedly attempting to stab Deputy Chief Olson.

Wednesday Afternoon Rally

Despite the fact that most reports placed very few university students among the rioters, in those days anti-authoritarian sentiment ran strong among the UM student body. A hastily-assembled alliance of campus radicals and student government officials called a rally for the afternoon of Wednesday, June 18, to collectively decide on what immediate action, if any, should be taken as a result of the previous night’s confrontations.

Nearly a thousand people attended the rally. A vote was taken as to whether or not the group should demand that South University be closed to make a pedestrian mall. By most accounts the result was a resounding “no.” Attendees were generally unreceptive to speakers who advocated for continuation of the confrontations with police, but many in the crowd showed an inclination toward further conflict.

The Third Night

Urgently desiring a peaceful end to the conflict, university and city officials decided to organize a rock concert on campus for the evening of June 18, hoping to draw people away from the South University area. The concert began at 8:30 p.m. in Jefferson Plaza in front of the university’s Administration Building, about half a mile from where the previous night’s altercations had occurred. More than two thousand people showed up for the free entertainment.

In addition to rock music, attendees also heard speeches by President Fleming and Mayor Harris. In his speech, Harris modified somewhat his position on the police actions of the previous night. He continued to defend the behavior of the Ann Arbor Police. But he boldly stated that he would not defend the actions of Sheriff Harvey or his deputies.

When several in the crowd shouted condemnations of the sheriff, Harris replied, “I share your concerns about Sheriff Harvey,” then added, “There is nothing I know that I can do about that problem.” As sheriff, Harvey had jurisdiction throughout the whole county, including the city of Ann Arbor, and was not subject to the oversight of city officials. Harris also promised to set up a committee to look into the creation of a pedestrian mall in the contested area.

No police were in evidence at the concert. A short distance away, however, nearly three hundred lawmen from six different agencies lined the curbs of South University Avenue. An armored car with machine guns mounted in its turret sat menacingly in the street, and a police helicopter hovered watchfully overhead.

As the evening wore on, thousands of spectators made their way through the South University district, strolling the sidewalks or driving slowly by in their cars. But those hoping to witness another display of violence would be disappointed. The streets remained peaceful. A holiday atmosphere pervaded the area, with pedestrians chatting good-naturedly with law officers. By 11 p.m. the crowds had dwindled and the police withdrew.

Soon after the withdrawal, however, a crowd began once again to form in the street, blocking traffic. As the gathering swelled into the hundreds, university faculty and local clergy attempted to persuade the growing mass of people to break up and go home. Police were ordered back to the scene a little after midnight.

Nearly two hundred officers were deployed on either end of South University. Deputy Chief Olson ordered the crowd to disperse, then five minutes later signaled the advance. Police swept eastward and westward in a pincer movement, rifles leveled, bayonets fixed. The crowds were herded off South University and on to side streets. Around twenty additional arrests were made, with two civilian injuries reported. No injuries were reported among law enforcement personnel. By 2 a.m. the streets were all but deserted, and police left the area.

The Case of Dr. Edward Pierce

The conduct of both lawmen and demonstrators on Wednesday evening was markedly less pugnacious than that of the previous night. But more tales of police brutality soon began to emerge, perhaps the most striking of which was that of Dr. Edward Pierce, a physician who had responded to a request from university students for a trained medical presence on the scene. In addition to being a doctor, Pierce was also a former city councilman and mayoral candidate, and had been chairman of the local Democratic Party.

Pierce said that without provocation police officers knocked him to the ground, struck him repeatedly with billy clubs, and dragged him for 30 yards along the pavement to the bus that served as a paddy wagon. The Ann Arbor News quoted an unnamed police official as stating that Pierce had “attempted to cross a line of officers,” an accusation which the doctor denied. Pierce was arrested and booked on a felony riot charge. Within a few hours he was released, the felony charge having been dropped for “lack of evidence.”

The Fourth Night

During the rock concert on Wednesday evening, city officials and university faculty had circulated among the crowd, engaging in open dialogue with the young people in attendance, urging calm. Encouraged by the relative success of these efforts, city officials decided to gamble that a contingent of civilian peacekeepers would be more effective at maintaining order than would another show of force by the police.

An agreement was reached between city government and law enforcement officials to keep 175 officers and state troopers on standby at a staging area near South University while city officials, university faculty, and White Panthers worked together to calm the crowd and keep the roadway clear. The evening of Thursday, June 19, would see no uniformed police presence on the streets.

Although the situation became tense at times, the results of the “no cops” approach cannot be called anything but successful. For the most part the streets were kept open. There was no violence other than what might be expected in a large crowd where alcohol was being consumed freely – and in which members of the God’s Children Motorcycle Club were present. Mayor Harris came twice to the area to talk with the gathered young people and urge them to go home. By midnight the crowds had thinned significantly. Around 2 a.m. it began to rain hard, sending the last few holdouts to seek cover.

The Battle of Ann Arbor was over.

About one month later, South University Avenue would be barricaded once more – but this time there would be no bayonet charges or tear gas barrages. It was the annual Street Fair, the tiny predecessor to today’s mammoth Ann Arbor Art Fairs. On the same four blocks where a month earlier rocks, bottles, and obscenities had been flying, and no little amount blood had been spilled, respectable townies mingled peacefully with the hippies, eating ice cream, browsing the art, and perusing sale merchandise on the sidewalk.

The Aftermath

That tranquil setting, however, belied the deep-seated animosity that continued to exist between conservative-minded townsfolk and the bohemian street people. Over the following weeks, the majority of the letters published in The Ann Arbor News about the South University disturbances were strongly pro-police or anti-hippie, often both. Some were quite passionate in their condemnation of the street people. One writer wanted to “form a Pied Piper Club to rid the town of rats,” i.e., hippies.

On the other hand, letters published by The Michigan Daily were almost universally anti-police, and especially anti-Harvey. The sheriff, who was known to have his men cut the hair of young people sent to the county jail, was the arch-enemy of much of the town’s non-conformist crowd. A recall effort directed against Harvey that had been mounted by radicals a week before was given a considerable boost by the South University affair.

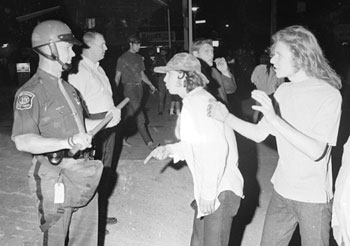

June 19, 1969: Mayor Robert Harris circulates among the crowd on South University. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

The sheriff was not the only one to be loudly criticized for his actions during the disturbances, however. Mayor Robert Harris, in office barely two months when the streets exploded in violence, was attacked from both sides – from the right for not hitting the hippies hard enough, and from the left for not doing enough to hold back the police, especially Sheriff Harvey.

Harris was only the second Democrat to hold the office of mayor in Ann Arbor in nearly forty years. Soon after the riots, a Republican-led group called Concerned Citizens of Ann Arbor started its own recall campaign against the mayor and the Democrats on city council. Although none of these succeeded (neither did the recall of Sheriff Harvey), Republicans would win back the mayorship four years later, in part by playing off the Democrats’ supposed over-tolerance of hippie-led disturbances such as those on South University.

Harris, who had publicly criticized Harvey’s conduct during the disturbances, also found himself of the receiving end of reciprocal verbal assaults from the sheriff. Harris’s own city police force even turned against him, openly stating their dissatisfaction with his handling of the South University affair. Oddly, they seem to have been angry at not being allowed to put themselves in danger by forcefully clearing the street on Thursday night.

The Battle for Ann Arbor

The Battle of Ann Arbor, fought on a few blocks of city streets over four mild June nights in 1969, should probably be counted as a draw. The radicals and street people did not succeed in “liberating” South University. But the forces of law and order were not much more successful. Of the approximately seventy persons arrested during the fracas, only a handful were convicted, mostly of misdemeanors. Many charges were dismissed without trial. As near as can be determined, none of the more than thirty who were arrested on felony charges of inciting a riot were found guilty of such.

Ultimately the issue at stake was not the making of South University Avenue into a pedestrian mall. Rather it was a deeper conflict between two seemingly incompatible ways of life. The “straights” had made Ann Arbor their home for more than a century. The hippies had come to Ann Arbor only recently, but were now also calling it home. Each group wanted to the city to be a place where they could conduct their lives in the manner they thought best. Each felt the other was undermining their efforts.

The same situation was being played out to varying degrees in hundreds of towns and cities across the country during the 1960s. In Ann Arbor the conflict of long hair with short, new ideas with old, and youthful abandon with middle-aged restraint would last longer than in most other areas. In the decade following the South University conflicts, the balance of power would first tip one way, then the other. For example, Ann Arbor’s (in)famous “five-dollar pot law” would be enacted in 1972, then repealed in 1973, then reestablished as an amendment to the city charter in 1974. The city’s marijuana laws have remained a subject of contention ever since.

The Battle of Ann Arbor was only one part of a larger struggle, the Battle for Ann Arbor – a struggle that in some ways remains unresolved to this day.

About the writer: Alan Glenn is currently at work a documentary film about Ann Arbor in the ’60s. Visit the film’s Web site for more information. While there you can contribute your memories of that time – and read those that others have contributed – in a public forum set up expressly for that purpose.

Absolutely fascinating! I thought I was reading about Alabama, but no, it all happened in our own town. I’m certainly glad for today’s Ann Arbor and would not trade it for any other place in the world!

40 years later, the proposal for a pedestrian mall on South University still holds weight. If only its merchant association would stop visioning that space as a “Cambridge, MA” and take heart that they are the one and only Ann Arbor, the dreams of the past would play in to a greener today.

Amidst Ann Arbor’s current socio-economic troubles, and those of the state, it’s very easy to forget that Ann Arbor was the birthplace of a lot of democratic (with a lowercase d) and civil rights activism and history, particularly with the recent demonization of 1960s left-wing activism and its founders. Looking forward very much to the documentary.

Wow. That was a very interesting article! I really enjoyed reading it.

In Ithaca, New York, around this same period in 1969 a group of Cornell students also sought to establish a “Peoples Park” on Eddy Street, a few blocks from campus. As I recall it, this park only meashured about 10 by 10 feet next to a local drinking establishment, Maurie’s. Ithaca’s mayor, a former Marine, Jack Keily, learned of the event and quickly visited the location. After hearing the students demands, he read a short proclamation declaring the designated plot as Ithaca’s Peoples Park and later had a resolution introduced in Common Council to that effect. After a few drinks, the crowd broke up and everyon was pleased with the result. I think that little square of conrete and grass still sits open today and a few locals still know it as the People’s Park.

I’ve heard the Regent’s Plaza (near the Fleming Buildng) called the People’s Plaza; don’t know the origin of that.

There’s a great picture of student protesters on South U inside Hole Foods near the east side door.

The University never wanted to turn South U into a pedestrian mall. They did want to turn East U into a mall, and succeeded many years later, just as they did on Ingalls and part of Monroe and are now trying to do on another part of Monroe.

Jefferson Plaza was renamed Regent’s Plaza at some point, but The People (as in “Power to The People”) renamed it People’s Plaza. At that time there were weekly rock concerts in the Plaza, usually with The Up.

I was an undergrad at the time and was present for at least one of the nights in the article. My recollection regarding the arrests for “contention in the street” is that charges were ultimately dropped when the court concluded that there is no such crime.

In recent years I have seen the AAPD respond to unauthorized marches by closing off street to traffic so that no-one would get hurt – a welcome change in tactics.

Great article. Brought back alot of memories of the revolution.

Re #6 — Ed, the “People’s Plaza” for the area next to the fortress-like Fleming building (with its all-brick first floor) strikes me as a sardonic reference to the Protect-the-Establishment architecture of the Fleming building!

Photographer Andy Sacks has a collection of 1969 Ann Arbor photos on his site Saxpix:

link to photos

with some good shots of Sheriff Harvey in action.