Washtenaw Jail Diary: Chapter 1, Part 2

Editor’s Note: After the break begins the next installment of the Washtenaw Jail Diary, written by a former inmate in Washtenaw County’s jail facility on Hogback Road. The piece originated as a Twitter feed in early 2009, which the author subsequently abandoned and deleted. See previous Chronicle coverage “Twittering Time at the Washtenaw County Jail.“

Editor’s Note: After the break begins the next installment of the Washtenaw Jail Diary, written by a former inmate in Washtenaw County’s jail facility on Hogback Road. The piece originated as a Twitter feed in early 2009, which the author subsequently abandoned and deleted. See previous Chronicle coverage “Twittering Time at the Washtenaw County Jail.“

In now working with the author to publish the Washtenaw Jail Diary, The Ann Arbor Chronicle acknowledges that this is only one side of a multi-faceted tale.

We also would like to acknowledge that the author’s incarceration predates the administration of the current sheriff, Jerry Clayton.

This narrative, which we expect will run over a series of several installments, provides an insight into a tax-funded facility that most readers of The Chronicle will not experience first-hand in the same way as the author.

The language and topics introduced below reflect the environment of a jail. We have not sanitized it for Chronicle readers. It is not gratuitously graphic, but it is graphic just the same. It contains language and descriptions that some readers will find offensive.

Suicide watch

There’s some silence. Then Charlie tells me that now I will probably stay in Bam Bam longer than I should. He turns out to be correct.

The detoxing teen heroin user asks, “Do you really work for Channel [_]?” I say I do, then think that I will likely lose my job now. I am right.

Eventually, Charlie goes back to his block. Heroin teen goes home. Each time the officers come, I cite the number of hours I’ve been without my phone call. I have not eaten any of the meals offered. It is the beginning of the Washtenaw County Jail radical-weight-loss plan for me.

I am alone in Holding 4, half-naked in my Velcro Bam Bam suit. It is approaching evening. I think of my wife and children, I think of the humiliation when my coworkers find out. For the first time today, I break down into sobs.

I spend the night in Holding Cell 4 and manage to fall restlessly asleep. Then, the “suicide watch” feature of the accommodations kicks in.

When I read, or write, about “suicide watch” in the news, I picture a team of nurses and psychiatrists asking the prisoner how he “feels.” Now I learn what really occurs.

At night, a guard runs by the cell every two hours and bangs on the window. If you startle, you’re alive. If you do not move, then the officer’s extensive psychiatric training kicks in. The guard will enter the cell and poke you with his finger. If you move, you’re alive. Next patient, please. That is suicide watch.

Holding Cell 3

It is again morning. I have been in jail a day now and it has already changed me permanently. It is too much to hope that I can simply wait out my time in Bam Bam with a holding cell all to myself. I am transferred to Holding 3. “Break 3!” the guard screams to desk officers who release the sliding doors.

I enter into a crowded holding cell, and the biggest nightmare of my life.

First thing that hits me is the smell, then the solemn faces that look up disinterestedly. My first day was nothing, a picnic. Here is the real Bam Bam.

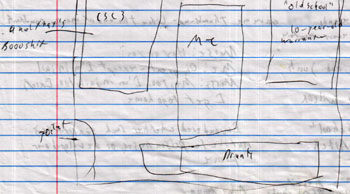

This is the bottom half of the author's sketch of Holding 3's layout. From the center, clockwise: Me | "Old School" 10-year old warrant | Drunk | Toilet | and that's booshit

There are five inmates in Holding 3. I am the sixth. Six can lie down semi-comfortably on the ledges and the floor. I throw down my foam mat.

To my left is a man lying on two foam mats – relative comfort. Yet he grimaces. He had fallen down courthouse steps while in leg irons and handcuffs. He takes one glance and, again, there must be something about me that gives it away: “You’ve never been in jail before,” he says.

To my right is an elderly black man everyone just calls “Old School,” which is a kind of label of respect for all older black men in jail. Older white men, in general, do not merit an “Old School” designation. Usually, they are called “Pops.”

Old School, in Bam Bam due to a heart condition, doesn’t know why he’s in jail. He shows me a court paper. Something about a 1992 case. As best as I can tell, Old School was pulled over for DWB (driving while black) and his name came up in a ’92 warrant for a traffic offense. So they haul a confused, old man with a heart condition into a filthy, crowded holding tank in an overcrowded jail. Nice, Washtenaw County.

For unexplained reasons, Old School looks to me as a reliable source of information on what is going to happen to him. I try as best I can. It is the beginning of a trend. Fellow inmates can tell I am new in jail, but also sense in me some kind of unearned intellectual authority. I will be called upon to settle arguments about wide-ranging topics during the course of my five months in the Washtenaw County Jail. My advice to Old School is the start of a kind of career in jail. Later, I branch out into ghost writing speeches for inmates to give before their judges. In the end, I will be proud of how I behaved toward others (with some very dramatic exceptions) in an extremely stressful environment.

But, for now, there is only anger, distress as my rights are denied and as I take in what is happening in this increasingly crowded cell. In the right corner of the cell sits a man I’ll call “Frank,” a muscular black man in his 30s with a weary-looking face. He has been in Bam Bam for three months. Frank is in suicide watch by choice. It’s a last-ditch defense tactic. Charged with armed robbery, Frank is going for an insanity defense. Anyone who willingly subjects himself to Bam Bam must be crazy, his reasoning goes. So he refuses to see a shrink, refuses to go to a block.

In every part of the jail I live in the next five months, there is always one experienced person who takes me under his wing. Frank does this for me in Bam Bam. Frank had heard my confrontation with the guard in Holding 4. He thinks I can tell his story to Channel [_]. I am sorry, Frank. My old employers now want nothing to do with a convicted criminal.

During my first month in jail, I would have vivid, epic dreams in which I try to make it back to work to tell the reporters what I’ve seen. Later, I would learn that even in a “news” organization, nobody is interested in the lives of convicted criminals. Jail. End of story. But, again, I get ahead of myself. I am still in my second day at the jail and I am living in an increasingly crowded, filthy holding tank.

And in walks the accused rapist.

Flush on 3

I will see him on and off for the next three months – as his case goes back and forth from 2nd-degree to 3rd-degree “criminal sexual conduct.” I will know more about his case than I care to, since he talks endlessly about it – going through the same story over and over again. I have noticed already that there is very little real conversation in jail. Instead, everybody seems to be carrying on parallel monologues. One of the best compliments I receive from an inmate will be spoken in a couple of months: “I like you, [______]. You listen, then you talk.”

But the alleged rapist is a man – a child, really, at 19 – who does little listening and a lot of talking. He has an almost intelligent look about him, with a goatee and glasses. But the illusion is shattered when he opens his mouth. He practices his “story” on us. The woman who accused him of rape is his first “baby mama.” His second “baby mama” cried in court, which made him cry. So, he was sent to suicide watch.

Rape Boy says that he has text messages from the alleged victim telling him to do her doggy style. He says this over and over again. He also says there must be apartment surveillance video showing that she had buzzed him in many times. Later, I will share a courthouse holding cell with him and hear, with satisfaction, his lawyer say that none of these things are a defense. But, for now, I just listen to this 19-year-old kid talk endlessly about his “baby mamas” and what he’ll do to each of them when he gets out.

By now the stench is approaching unbearable. Frank gets up and pounds on the cell window. Frank pounds a few times before he has a guard’s attention. Then makes a twisty motion with his fingers. “Flush on 3!” Frank yells. “Can you give us a flush on 3?”

We do not operate our own toilets. It is the loudest flush I have ever heard, filling the cell with sound, halting all conversation for about 30 seconds.

Bricks and Butterfingers

A nurse comes with medication. I tell her how many hours I have been in jail without my phone call. She does not look very interested. The nurse asks me how I am. I say I’m fine, except I’m in jail. She says that she’s in jail, too. “Except I get to go home.” Such compassion.

I am seen by a community mental health worker. He questions me and determines I am not suicidal, says he will recommend I be taken out of “checks.” I am not comforted by this. I know that although the booking officers are about 15 feet away, my paperwork will likely get “lost” as a result of my earlier confrontation with the officer.

More people are packed into the cell. The air is thick with unpleasant odors and the walls seem to be closer. I stare at the white bricks, feeling helpless and hopeless. No contact with my family, no knowledge of when I will be allowed contact. I gaze at the bricks and wonder how it would feel if I bashed my head against them.

I came to suicide watch with no thoughts of suicide. About 40 hours of denial of rights, of no hope, of no information, and all options are open.

To distract myself and to keep my mind from spinning into a dangerous loop, I strike up a conversation with the heroin addict in the corner I’ll call “Jack.” Jack’s stringy hair hides his eyes, forcing him to jerk his head back in nervous nods now and then. Jack insists he had hidden a heroin syringe in his shoe, somehow transferred it to his jail sandal, only for it to fall out on the walk to Bam Bam. It was to have been Jack’s last fix before detox in jail. He’s quitting for good, he says, having spent too much of his wife’s money on his habit.

Jack’s wife has a honorable, professional job. And while she works all day, Jack stays in the basement – shooting up. Great arrangement. The happy couple – heroin addict and respected professional – dipped into retirement to pay off court costs. He was going to leave jail with a clean slate. The nurse had given Jack something. Not sure if it was methadone. It relieved his withdrawal symptoms. Now, though, he craves Butterfingers.

I ask Jack what it felt like the first time he tried heroin. He grins deeply at the memory and says it was 10 times better than sex. But now, for Jack, nirvana can be achieved only through Butterfingers bars via a magical place – on a real cell block – where inmates can have rights to something he calls “commissary.”

Jack talks so much about Butterfingers that his obsession becomes my obsession. I have eaten little in 40 hours. Butterfingers sound nice. My first taste of jail has been Bam Bam, the worst place to be outside solitary. I wonder what’s next. I think about this “commissary” and Butterfingers.

Sights, scents and sounds

The drunk enters the tank, swearing up a storm. He’s tall, thin and talks to nobody in particular as he lies down near the toilet in back. “I blew a motherfucking .08. So fucking what? To me that’s just a fucking hangover. So they put me in fucking Bam Bam? Fuck!” Then he pukes. The drunk’s puke is not cleaned during the rest of my stay in Bam Bam – still roughly 12 hours to go in that tank. The smell lingers.

It has been 42 hours since I “disappeared.” No contact allowed with family. I’m laying half-naked in a crowded cell with the stench of puke.

But I’m not the only one feeling uncomfortable. On the floor ahead of me is a guy with long, gray hair moaning, “I need my crack pipe!”

The drunk is sleeping it off in his own puke, snoring and slaying some demons in his sleep, and the odor of shit cuts through. Charlie sees me wrinkle my nose and nods knowingly. He says there was a Mexican guy in here a few days ago who didn’t make it to the toilet. The cell was never properly washed and you can still pick up the odor of shit when the vents start pumping out air. Like now.

I try to sleep with the overwhelming smell of human waste. Then I learn the other reason they call this area of the jail Bam Bam.

Bam! Bam! The sound comes from Holding 2, which is usually reserved as a cell for inmates waiting for transport to and from court. Tonight, Holding 2 must be either a Bam Bam spillover, or it’s where drunks come to sober up without actually being booked into the jail.

Bam! Bam! The pounding gets louder. His is the only voice you hear. “I want a fucking cup! Where’s my fucking cuuuuuuup!” Bam! Bam! “This is like fucking Guantanamo, man. Guantanamo. Where’s my fuuuuucking cuuuuup!” Bam! Bam! Bam!

Eventually, we learn to ignore him. Cup Man goes on all night. Not an exaggeration. All … Night.

He does, however, get me thinking about the Guantanamo comparison. But Guantanamo is not in my frame of reference for the situation I am in. I come from a family of Holocaust victims and survivors. Auschwitz. I do not go screaming “Auschwitz” and “Holocaust” everywhere. I am not the kind who sees Nazis in the woodwork. I know I am not in Auschwitz. But, the way I feel, the filth I am living in, huddled in a crowded cell, my right to contact my family denied. I think of those pictures of bewildered skeletons after liberation. I understand that is not where I am. Yet, it is how I feel.

I try to use the comparison to my advantage. I think of what my great-uncle endured in Auschwitz and decide this is nothing in comparison. It’s a selling point, I joke to my increasingly insane-sounding mind. “Washtenaw County Jail Suicide Watch: At Least It’s Not Auschwitz.”

Bam! Bam! “Where’s my cuuup!” Cup man shouts. Rape Boy in the corner is boring another victim with his story: “Yeah, Dog, she texted me to turn her over and do her doggy.”

The repetition makes me think, hope, that this is all a bad dream.

Good Cop

“I have been here 48 hours now and I still have not been allowed my phone call.” The officer looks bored, looks through me.

It had been a horrible night, between yells of Cup Man, the repetition of Rape Boy and the every-two-hours window banging of suicide watch. I approach Day 3 resolved to get out of Bam Bam and get my phone call. I see others come and go. I see others making calls. So it’s possible. I try to think logically, although my base-coat of panic is never far from the surface. Who knows how to get things done? I turn to Frank.

Frank has been here so long that he knows which officer will help you out and which to avoid. He points to a tall, older man in civilian clothes. “He’ll get you your phone call and get you out of here,” Frank says. And he’s right. It will take about 8 more hours, but he’s right. The man Frank points to is a distinguished-looking sergeant.

Every now and then, the sergeant walks from holding cell to holding cell – not opening the doors, but placing his ear nearby and listening. It looks like he is used to cleaning up the messes his officers have made. I am one of those messes. I guess you’d call him the “Good Cop.”

Good Cop listens intently to inmates through glass windows, jots down names and notes, moves on. I wave for his attention … too late. Cart pushers come in with trays. Good Cop disappears back behind the officers’ glass. Another meal for me to reject is pushed in. I still have eaten very little since my arrival. I pick at my food a little, then give most of it to Frank, who devours it appreciatively. It sickens me a little to watch that garbage being eaten so quickly. But I am beginning to understand how food is used as currency in jail. Frank gave advice on how I can get my phone call. So he gets my food tray. I’ve not yet experienced the deep, deep hunger I will feel later.

“. . . and that’s boooshit,” says Rape Boy. That’s pretty much how he ends every story he tells, since most are about how he’s been wronged. Another story about his “baby mamas,” then he turns to me and says something I never saw coming.

Rape Boy says the name of an anchorwoman at the TV station where I work and asks if he could meet her.

I say I likely would not see her again.

Then he asks if I am going to “put Washed-Away County Jail on TV” or tell “the news” what goes on in Bam Bam. I say I will try.

“They should do something on Old School,” Rape Boy says, pointing at the old man. I agree that they should, but they probably won’t.

Frank nods. “We’re in jail,” Frank says. “Out of sight, out of mind. Nobody wants to see us on TV after we’re in jail.” I agree that he is right. Then Frank adds: “But you’ll go tell [name of anchorwoman] about Old School. She’ll put him on TV.” I smile in a noncommittal way. “I don’t think I’ll be telling any anchorwomen about anything when I get out,” I say. “I don’t think I’ll have a job anymore.”

Then Good Cop comes out near the cells again. I bolt upright, run to the window and bang for his attention. Bam! Bam! “Excuse me, sir?”

And here I am, saying words that, about 50 hours earlier, I could never have imagined would come from my mouth.

“Excuse me, sir? I have been in Bam Bam 50 hours, was cleared after 24 hours as not suicidal and I have not been allowed my phone call.”

“Wait wait, one thing at a time,” Good Cop says patronizingly, taking out a notepad. “Who cleared you?” I freeze. No idea what his name was. If he had told me his name, it didn’t stick. So I think of his identifying features. “An Asiany looking guy who smiles too much,” I say.

“OK. If he cleared you, then there’s no problem,” Good Cop says. I tell him that the paperwork was somehow lost before it reached the desk. He stops writing and glares at me. I am guessing he knows that if the paperwork was “detoured,” then I must have caused some trouble.

Good Cop is the first apparently sane person I have spoken to since the ordeal began, so I start speaking faster to tell him my whole tale. “Whoa, slow down,” he says. “You claim you were cleared, but there’s no paperwork showing it. You’re in checks, so no phone call.” My heart sinks. Back where I started. It’d be funny if I did not have a role in this joke.

“To my family, I’ve just disappeared,” I say.

Good Cop is well aware of the Catch-22 involved in cases like mine. In the end, there are no rules. There is simply the judgment of an officer.

For a brief moment I see a light go on in Good Cop’s eyes. He is assessing me. I think I pass some kind of test. “I’ll look into it,” he says. He is the first cop I encounter in jail who is not lying when he says that. There will be only one other.

The door to Holding 2 slams shut and for the first time I think about what exactly I’m going to say to my wife once I get my call. It is going to be a bad conversation. My thoughts turn full-time back to the real world now. I do not expect to be in jail more than another day or so. Need to salvage my life. I think of what a mess I’ve made of things and I start to feel physically ill.

I will discover later that it is best to turn off the portion of your brain that makes you think too much about life outside of jail.

“You’re getting out of Bam Bam soon and going home,” Frank says. He turns out to be half right.

Frank tells me not to forget about them when I get out and to tell everybody about what goes on in Bam Bam. I do not forget. Later, my public defender will advise me not to write about this experience while I am on probation because of possible reprisals against me. I am now ignoring that advice. It is one reason I am writing anonymously.

Editor’s note: All installments of the “Washtenaw Jail Diary” that have been published to date can be found here.

Kudos to the Chronicle for running this series.

Have you sent copies of the two installments to Sheriff Clayton? I hope.

This is a fascinating account of what’s it’s really like to be in jail. Thanks to the Chronicle for providing this unusual story. And to the author: I can absolutely relate to your obsession with the phone call. I would feel EXACTLY the same way.

Once again, my thanks and admiration for putting this story out. I am increasingly impressed with the social significance of stories found in the Chronicle compared to most other “news” sources. And the importance of the comments following major stories is surprising and helpful for mulling over the interpretations of the material just read.

The army’s basic training is not as brutal as this man’s in our local jail but if he had had that experience behind him, I suspect he would have handled this situation better. No one enjoys the treatment received when entering the armed services but I suspect we are a little better fitted for some of life’s traumas as a result.

I imagine that treatment plus the realization that your life is never going to be the same again can hit you pretty hard. From the perspective of my pretty-cushy-so-far life, it seems hardly survivable.

What’s described here is frightening to contemplate. I get claustrophobic just reading the story.

I just hope this guy has owned up to his crime and sees that this is his fault and not the fault of anyone else.

To compare his experience to his Jewish ancestors is pretty cheap, even by his own admission, but he missed a fundamental point: They went to Auschwitz for being Jewish. He went to jail for being a criminal. BIG DIFFERENCE. In essence, he chose what he received.