Ex-Radicals Remember Robben Fleming

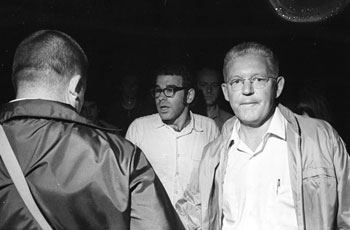

UM President Robben Fleming at a press conference during the Black Action Movement strike in March 1970. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

On March 12, 1968, Robben Wright Fleming was inaugurated as the ninth president of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. It was a time of great turmoil on college campuses across the country, especially at Michigan, which was in the vanguard of the radical student movement. Fleming had been hired to replace the retiring Harlan Hatcher largely because of the reputation he had built for controlling student unrest while chancellor at the University of Wisconsin.

Fleming’s background was as a labor negotiator, and he preferred to engage students in reasoned discussion and debate rather than send in the riot squad. As he related in his autobiography, “Tempests into Rainbows,” after learning of his interest in taking the top post at Michigan, the regents of the university invited him to the Pontchartrain Hotel in Detroit, where for two hours they talked mainly about how he would deal with student disruptions.

Fleming explained to the regents that he “thought force must be avoided insofar as humanly possible, that indignities and insults could be endured if they averted violence, and that … these problems would last for some unspecified time, but that they would eventually end.” The next day he was offered the presidency.

Fleming assumed the helm in Ann Arbor in 1968 – the most turbulent year yet in an increasingly tempestuous and troubled decade. Over the next three years he would face an escalating series of crises that would severely test his negotiatory approach to student unrest. There were protests against classified war research and the ROTC. There was agitation for the creation of a student-run bookstore. There were three bombs exploded on or near campus. There were three nights of rioting on South University Avenue, a serial killer stalking campus co-eds, and perhaps the most challenging event of his term, the BAM strike of March 1970.

The Black Action Movement was a loose coalition of African-American students and faculty united in the common purpose of expanding the minority presence on campus. BAM called for a campus-wide strike until the university agreed to meet their demands – chief among which was a commitment to increase black enrollment from 3% to 10% over the next four years.

Demonstrators disrupt a ceremony at Hill Auditorium during the Black Action Movement strike of March 1970. President Robben Fleming stands at the podium. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

The BAM strike was led by black students and faculty, and remained so throughout its nearly two-week duration; but white radical groups quickly became involved in a supporting role, and before long the normal operations of the university were being significantly impaired. Negotiations were conducted per the president’s usual style, but as days passed and no agreement was reached, tensions on both sides began to mount. Fleming was under increasing pressure to end the strike by force.

Just as it seemed that the situation might boil over into violence, however, there was a breakthrough at the negotiating table. An agreement was struck, the strike was called off, and bloodshed was averted. Fleming’s handling of the BAM dispute is often counted as one of his finest moments.

In that regard it is interesting to note that praise for Fleming’s presidency at Michigan tends to consist not of positives but of negatives – what he did not do. He did not lose his temper when dealing with student radicals. He did not in general respond to disruptions with force, as others might have done, and as some encouraged him to do. He did not call out the National Guard. He did not escalate conflicts until someone was killed.

Of course Fleming did on occasion use force to resolve standoffs with students. But he seemed to have an earnest desire to avoid conflict whenever possible, and when resorting to force he planned the action so as to minimize violence – for example, working to ensure that demonstrators occupying a building had an opportunity to escape out the back way as the police moved in.

Fleming’s seemingly conciliatory approach – as well as his public statements against the war in Vietnam – tended to give the impression that he sympathized with the student protesters and their causes.

But the president himself was the first to say that he acted as he did not out of sympathy but because of his reasoned judgment that a more extreme response would ultimately be counter-productive. As chancellor at Madison, Fleming drew the national spotlight after using his own personal funds to post bail for 11 student demonstrators who had been arrested following their occupation of a university office. He later explained that he did this not out of compassion but rather to prevent the students from becoming martyrs to their cause.

After Fleming’s death on Jan. 11, 2010, at age 93, many eulogies appeared lauding his tolerant, enlightened leadership during what was probably the most calamitous period in the history of the University of Michigan. Almost without exception these were based on Fleming’s own view of events, as put forth in his memoir, and the recollections of his colleagues and friends in the administration.

Those who faced him from the other side of the fence sometimes remember Robben Fleming a bit differently. A number of former activists who had occasion to interact with the late president provided their thoughts and impressions via phone and e-mail.

Steve Nissen: Human Rights Party

I was very engaged in activism at the University of Michigan when Robben Fleming assumed the presidency in 1968. He came to the job with a reputation for adeptly handling the turbulent student protests while at the University of Wisconsin. I found him more approachable than his predecessors and willing to engage in discussions with student leaders, which distinguished him from the aloof attitudes of other university leaders.

He didn’t make huge changes, but his openness gained him some increased respect and cooperation from the more moderate student elements, which I was not. However, he was not popular with tough-minded student activists because we were all functioning in a highly polarized environment and there wasn’t much room for compromise.

In my case, we disagreed, but our relationship was not disagreeable. He was soft-spoken and never strident in relating to student leaders, but he did not yield much, either. Given the times, he was probably as good a choice as possible as a college president for a troubled era.

Bill Ayers: Students for a Democratic Society

I had an interesting relationship with Robben Fleming and it continued long, long after he was president of the University of Michigan. We reconnected after I became a professor at the University of Illinois. He was in Chicago doing some work with the MacArthur Foundation. We had coffee and that became something we did periodically.

He told me years later that one of the things that was difficult for him was not the heat that he was getting from the students, it was the heat from the trustees [regents]. The trustees looked to people like Clark Kerr [at the University of California] and thought that that was the smart way to go, to hammer these students. Fleming, I think largely because of his background as a negotiator and a labor professor and so on, was more inclined to negotiate. He wasn’t a kind of Neanderthal standing at the gate insisting he had the only view. He always wanted to know what you thought.

The night that I remember most vividly was the last day of March, 1968. Lyndon Johnson had gone on television and announced that he was not going to run for president, and he would work to end the war in Vietnam. And we poured out of our apartments and we had this kind of spontaneous rally that raced through the streets of Ann Arbor and ended up on the steps of his house there on South University.

I had a bullhorn and Fleming came out and he had a bullhorn and what he said that night I remember absolutely vividly. He said, “You’re to be congratulated. You’ve won a great victory. You’ve ended this war.” And I think he believed it that night. I know I believed it. A few months after that it was clear the war would not end, but would escalate. But on that night, March 31, 1968, in the middle of the night, standing outside his house with 1,500 students trampling the rose bushes, he was calm and he was clear and he was congratulatory and that’s the kind of guy he was.

I think he genuinely thought that the war was a mistake. I don’t think he had a critique or an analysis that was against imperialism like we did, but I think that he didn’t think that the war was a good thing. I think the evidence for him of why the war was not a good thing was that it was tearing up the country.

He wrote a memoir about those days and as I remember it, he said at one point that while he and I had differences, we were always fairly civil with each other. It struck me as funny when I read it because I was remembering that night of March 31, 1968, when I was basically shouting, “Fuck you, you motherfucker,” into a megaphone, and he remembers it as I was always reasonable. I don’t think I was always reasonable, but he was a pretty reasonable guy and I think he believed in the power of reason and the importance of evidence.

Madison Foster: Black Action Movement

I have respect for him, that’s the first thing I want to establish. Respect as a scholar, an intellectual, and after I negotiated for the Black Action Movement, I have respect for how he negotiated. And also how things came out, and how he followed up afterwards. When he did make promises when he negotiated, he delivered on them. So in that sense I have nothing but positives to say about Robben Fleming.

As a negotiator Fleming was good. At first he tried some divisive things, but that’s okay, that was the name of the game. It was leaked to the press that the strike was over, and many students heard the news and backed off, and we had to go back and regroup again. Fleming threatened us early on to call the National Guard, and I for one called his bluff by simply saying, “Well, I guess we’ll die,” and we walked out. I wasn’t going to negotiate under threat, so I called his bluff, and he didn’t bring in the National Guard. [This would have been about five weeks prior to the shootings at Kent State.]

From my understanding, one of the reasons Fleming was brought to Michigan was because of the general student conflict at Berkeley and other places, and the left radical organizing that had been going on at Michigan. They were expecting some conflict to come off from white students. They didn’t expect the conflict to be led by black minority students at the time.

I would say the BAM strike probably was one of the few successful, if not the only successful student strike of that period – in the sense that we got about 90% of the demands. But at the same time much of that was because of who Robben Fleming was.

Picketers in front of the University of Michigan's Hill Auditorium during the Black Action Movement strike of March 1970. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

I had the feeling that he was open to having more African-American students enrolled at the university, that he wasn’t opposed to it. I can’t say for sure. If I had to guess I would think he was personally sympathetic. But he was a true negotiator. Don’t forget that. He was all pro.

I would credit him with keeping the lid on generally – there weren’t any casualties at Michigan, in spite of the fact that Michigan was probably the second-most radical activist hotbed after Berkeley, during that period. During the BAM strike, I wouldn’t credit him for keeping the lid on, I would credit the BAM leadership. We used conflict, but we kept some of the hotheads from doing violent things, both black and white. But I credit Fleming for not escalating the conflict by calling in troopers, or by escalating his rhetoric. In that sense he handled the situation well.

I tried to get to him. I got to him a little bit, once. He got angry enough to get up from his chair. We tried to keep him off balance, but he was basically calm. That’s what I mean when I say he was a good negotiator – he was calculating, and he was basically very calm.

Overall, I’d have to say positive things about Fleming. That might not be what some people want to hear me say, but that’s what I would say. I would say it if he were alive, to him. In fact, I did say it to him.

Eric Chester: Students for a Democratic Society

My experiences with Fleming were generally not positive. I found him to be a rigid personality, unwilling and unable to engage in a genuine give and take. Of course, I completely disagreed with his political perspective, but, even given this, I found other university administrators to be more likeable personalities.

During the book store sit-in [of September 1969], I was sent by the sit-in contingent to speak to Fleming. He said he would not negotiate on the issue of a university-run bookstore until we evacuated the building. There was therefore nothing to talk about and I soon left to report back to the sit-in group that Fleming was unwilling to negotiate. We were then arrested, and at a meeting of the regents shortly afterward the administration caved in and created the bookstore. Pointless macho behavior by Fleming, but then I suppose that’s why they hired him in the first place.

I did not find Fleming to be courteous. I met him rarely in an informal, personal context since he made little effort to meet with student activists. When I did meet him, I found him to be a cold, calculating technocrat. I did not like him and I did not find him to be particularly competent in dealing with the issues we raised.

SDS activists were radicals and socialists. We saw ourselves as part of a larger movement for fundamental social change. Fleming was just a cog in the corporate hierarchy. It is difficult to see how we could have had two more different world views. Even on Vietnam, SDS called for immediate withdrawal from the start. Fleming was one of many corporate liberals who began to think it had been a mistake well after it began and were looking for a graceful way out.

Rennie Davis: Chicago Seven Defendant

Robben was a friend of my family. He knew my father, who was an economics professor at Michigan State. We spoke together at Hill Auditorium [in 1969] at a time when I was the “popular” speaker to the student anti-war audience and he came in to speak, did well, but it took a little courage on his part.

A rare president leading a great university from the courage of wisdom is my memory of Robben Fleming. In a time of student passion to change the world, I marveled at his ability to hold and honor the center when side-taking was all the rage. His spirit to see humanity in any side is a legacy that will inspire us always.

James Swan: Environmental Action for Survival

I recall being called to Fleming’s home on the day after the Kent State shootings. President Fleming quickly assembled a group of faculty and students who had been active on campus political events, and he sought their advice and support to prevent something like that from happening on campus. He was genuinely concerned about what had happened, and determined to avert something like that in Ann Arbor. The meeting was a very honest discussion with all people’s perspectives welcomed.

I always found Fleming to be an honest, sincere person who tried to lend a sense of dignity and open-mindedness to his position, as well as the university.

Gary Rothberger: Students for a Democratic Society

Robben Fleming was one of the first of a new type of university president, one hired not for the ability to charm alumni and faculty but rather one who could do crisis management. Whatever he believed personally, as president he acted to stop real change in the university while conveying an image of corporate liberalism. He was fairly good at seeming to want to resolve the issue, if not for the extremists and their unrealistic demands.

To deal with Fleming was to realize that he was a cold dude who didn’t care about anything else other than carrying out his assignment. He clearly disliked SDS, our ilk and our desire for democratizing society. And he clearly was determined to smash the student movement.

Robben Fleming during the June 1969 violent conflicts on South University in Ann Arbor. (Photo courtesy of Jay Cassidy.)

A particular example of both his ruthlessness and willingness to act as the hammer for cooperate liberalism occurred around 1970 or ’71 when one of the first UM lesbian organizations attempted to have a conference on campus. Fleming issued moralistic statements and refused to allow the conference to go on and refused to discuss the issue.

His false and much, much too belated public semi-opposition to the war not withstanding, I have no idea what his own personal views were on anything except that, eventually, you are what you do.

[On the second night of mayhem on South University in June 1969] two or three of us went to the presidential house. He came to the door and we told him that the police were creating a riot and were clubbing people and gassing them for no reason. He said that he did not see any “inappropriate” police behavior and that the cops wouldn’t gas people. I then tossed a gas canister into the foyer and asked whether he thought that was inappropriate. He sputtered and mouthed a few inanities and went back into the house.

A little while later he came out and made some sort on innocuous statement that meant nothing and he certainly was unwilling to call out the police for brutality. I had been in Mississippi, and in Detroit during some of the riots there. I know what extreme police brutality is and I’m not claiming that this was at the same level as some of that stuff. However, they were gassing people and clubbing people, doing it randomly and were obviously enjoying it. Fleming knew it, probably didn’t like it, but clearly was willing to ignore it because he thought to criticize it would have been politically unwise.

You are what you do. He did nothing when he could have spoken out.

Paul Soglin: Students for a Democratic Society (University of Wisconsin)

His greatest strength was his belief in himself and that rational discourse would carry the day. His weakness was accepting the Cold War rationalization that the state must prevail over independent thinking. He should have trusted his own beliefs and instincts.

Jim Toy: Ann Arbor Gay Liberation Front

We started the Ann Arbor Gay Liberation Front in the spring of 1970. Soon thereafter we got a message from the regents: “Will you please come to a regents’ meeting and tell the regents what Gay Liberation wants.” That day there must’ve been an overflow, because when I got there every seat was filled. So I said, “The regents have asked Gay Liberation to tell them what Gay Liberation wants, and I’m Jim Toy and I’m here to do that. Where should I sit?”

President Fleming, at the far end of the table, graciously stood up and said, “Mr. Toy, please have my chair.” So for the first and I would guess the last time in my life, I sat in the president’s chair at a regents’ meeting.

I told the regents what we wanted. Justice, in the sense of, for example, counselors trained to help people with concerns about sexual orientation. Changes in the curriculum. Changes to the university’s non-discrimination policy. And so on. And then they said thank you very much, and off I went. It would take more than twenty years before the regents would add sexual orientation to their non-discrimination policy.

In 1970 Gay Liberation Front requested university space in which to have a statewide conference. We received a formal letter from President Fleming denying use of space. There was a picket outside the president’s house, as I recall, protesting the denial. But a vice president of the Student Government Council said, “That’s okay, I have the keys to the Student Activities Building.” And so we had the conference.

I remember a friend of mine in Gay Liberation went to the Diag and burned a Bible. And President Fleming happened to be walking by, and said, at least by report, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you.” That was the extent of it.

If he got riled, he continued to be polite. And some people have been reported to say that this was one of his great strengths.

The author would like to thank all those who contributed to the writing of this story, directly and indirectly, with special thanks to Will Hathaway for providing a copy of his invaluable dissertation, “Conflict Management and Leadership in Higher Education: A Case Study of University of Michigan President Robben W. Fleming.”

Alan Glenn is working on a documentary film about Ann Arbor in the ’60s. Visit the film’s website for more information.

I knew Robben Fleming both as the son of senior faculty and as a reporter for The Detroit News who covered many of the crises that arose during his presidency (and don’t assume you know my politics because of who my employer was). I found the man to be very much the way he was described by Nissen, Ayers, Foster, Davis, Swan and Toy. I suspect that Chester and Rothberger remain the prisoners of what they see through their ideological lenses and that their comments reveal more about them than they do about Fleming.

On a personal level, Fleming could be warm and funny. But on a professional level, would anyone expect a skilled negotiator to be warm and fuzzy? I suspect if someone was calling me the vile names that Fleming was called, I would be cold, too.

I covered the June 1969 disturbance for The News, and yes, Gary, there was police brutality. I happened to have been gassed three times, whacked in the kidneys twice by police batons, and had my left shin split open by a chunk of brick thrown by a presumptive junior league SDSer (I was following a line of a half dozen Ann Arbor Police who were using tear gas to drive a crowd of circ 1,000 students and others up South University toward State Street. There was a small group across from Fleming’s house tossing stones and bricks at the police. I remember one person in the crowd yelling at the stone throwers “Aw SDS, get the ‘F” out of here … this is our thing.”)

If Gary really did throw a gas canister into Fleming’s foyer, I never heard about it. And isn’t it amazing that, if Fleming really was the way that Gary describes him, the U-M president didn’t make an issue of it. Fleming did get gassed, however. He was standing on his front porch talking with a crowd of students. The then deputy chief of the Ann Arbor Police and I were on the porch next to him. Then Washtenaw Sheriff Doug Harvey, one arm in a sling from a drag racing accident, snuck up the Diag with a couple of deputies, came up along side the presidents house, and lobbed a cannister that gassed cop, reporter, president, and assorted students. I wish I had had a recorder to capture the words the deputy chief had for Doug when he caught up with him 5-10 minutes later.

The Ann Arbor Police were staged at the corner of South and East U and worked South U up to State Street. Doug Harvey brought in either the Macomb or Monroe County Sheriff’s Departments (or both, I don’t remember) and the deputies patrolled the other end of South U and the connecting streets. I saw no AAPD clubbing (and Fleming wouldn’t have witnessed any, either, because he did not walk the streets, and all the law enforcement violence took place away from his house. I did witness dozens of young people being jabbed hard and hit with swung batons, all by various sheriff’s deputies. I caught it in the left kidney from a Washtenaw deputy who called me by name (his badge was covered and his face hidden behind a tinted plastic shield).

Stephen,

Its unfortunate that you misunderstood and thought that the point of all this was for you to describe how many times you think that you were clubbed. Alan Glen asked me for my opinion of Fleming and the current articles about him and his role at Michigan. I gave it to him. He printed it.

Fleming’s job was to prevent democratic change and stiffle opposition. He did so throughout his career. He also refused to intervene when people were being clubbed and gassed sought sanctuary on the campus from what was a police riot. He refused to do so, despite what was going on until forced to do so until events forced him to issue some sort of a statement. That is not changed by the fact that you believe you saw some demonstrators also engaged in violence.

The fact that some of the people quoted, most of whom I know, decided to describe him as conveying to them a “secret” life less odious than his public life is part of what makes for wider discussion rather than the sentimentalized stuff that the media is currently publishing about him.

I don’t care whether Fleming was “warm and fuzzy”. The point is not whether he gave his seat to Jim Toy. The point is that the University refused to allow gay and lesbian students to even use meeting rooms. The point is not whether Fleming was a warm guy during negotiations with BAM. The point is that the U still only had 350 Afro-American students as of 2004. And that includes football and basketball players.

I could care less what he was like when you drank with him, got stoned with him or whatever you guys did when you were hanging out around the campfire. I do care cabout his role in opposing even the most basic democratizing of the U and society.

As to whether my statements as quoted in the article are accurate, believe whatever knocks you out. As to whether I (and Eric) am lost in the past, since you did not know me then and do not know me now I can only wonder why you are so into personalizing this. But one thing is clear, like your former employer the News, you seem to be more into demonizing people that disagree with your historical re-creations than getting at the truth.

By the way, I cannot help wondering why someone who worked as a reporter for the News would think that (s)he is in a position to comment on the credibility of others.

I’d really like to know how many of these radicals are now well-to-do conformists. I’m not bashing their accomplishments, they had a lot of heart to stand up for what they believed in. I just love irony.

Always good to get what people “could care less about” on the record.

I too found the article revealing. More so about those who chose to remain stuck so far in the past and clearly unable to see the bigger picture and clearly left bitter.

I’m pretty sure it says in the Constitution that baby boomers have the right to angrily explain how they were right all along until the end of time. It never gets old.

It is true that I never met Gary Rothberger, and perhaps it was a personal attack for me to argue that his written comments suggest that he is trapped in an ideological time warp. He attacked my credibility because I had worked for The Detroit News. So I guess the stories I wrote (and The News published) in June 1969 about sheriff’s deputies aggressively gassing and clubbing young people shouldn’t be believed either.

Let me repeat: As someone who grew up in Detroit, I cannot help wondering why someone who worked as a reporter for the News would think that (s)he is in a position to comment on the credibility of others. Simlilarly, I don’t know of anyone who disagrees with that sentiment.

Cain seems very wrapped up in his fantasies and daydreams about the 60′s and seems to get incredibly angry and hostil;e when anyone disagrees with him.

I’m not sure what an idealiogical timewarp is but I believe that the US is a country with an ever widening gap between the income of the very rich and that of working and poor people; that the US is still a racially segregated society; that it is harder and harder for a person without money to get a decent education and/or decent job; that those who run the economy are willing to destroy working people’s pensions and livelihoods, in fact are willing bring it down, in order that they might make a few million more; that the US government suuports and enables governments around the world that oppress, supress and murder people in order to stay rich and stay in power, that the US government actively seeks to bring down other governments that seek to empower their own people. I don’t see much that has happened in the last 40 years to change that opinion And that guys like Fleming spend their careers trying to prevent democratic change. But hey, Cain, if it knocks you out, be angry.

Whew. That was a mouthful. Well, now we know where Gary is coming from.

Gary’s responses are a primer on how to argue internet-style.

1. Deride any attempt to inject nuance into a controversial discussion as an apology for evil. It usually comes just before Godwin’s Law is invoked.

2. Claim a monopoly on the truth (“you seem to be more into demonizing people that disagree with your historical re-creations than getting at the truth”).

3. Deny someone’s moral standing to speak because of an association they once had (“I cannot help wondering why someone who worked as a reporter for the News would think that (s)he is in a position to comment on the credibility of others”).

4. Mix in some irrelevant claim to authenticity so you can look like you’re keepin’ it real (“As someone who grew up in Detroit…”).

5. Claim that everyone agrees with you. (“Simlilarly, I don’t know of anyone who disagrees with that sentiment”).

6. Project, project, project (“Cain seems very wrapped up in his fantasies and daydreams about the 60’s and seems to get incredibly angry and hostil;e when anyone disagrees with him”).

I think readers will decide for themselves where the anger is mainly coming from in this thread.

Well, I won’t know whether my commons are a primer for anything because I don’t spend any time doing internet blog comments. I was only doing this because the original article was sent to me by the writer who also mentioned the comments. I responded to Cain’s comments because it was so easy to do given the nature of his comments. As to your numbered comments:

1. Actually, I was responding to a comment that angrily attacked people for presenting a point of view that the commentator disagreed with.

2. Actually I was responding to Cain’s comments that seemed to focus on the supposed personality deficits of anyone who had a different point of view about Fleming. I don’t claim a monopoly on the truth. In fact, its Cain who does so. He attacks anyone who describes events that he wasn’t present when that description is contrary to the image of Fleming that he wants to spin out. And inplies that thye are lying. I didn’t challenge any of his facts. I just don’t think whether Fleming tossled him on the head when he was young has much to do witrh whether Fleming acted properly while prez of the U.

3. Actually I was responding to Cain’s cheap shots concerning my truthfullness and his attempts to bolster his credibility by referring to his former job at the News. And I don’t accept that the extremely well known News policies, distorting the facts, somehow knot to be discussed. I was also referring to his attempt to imply that any critisicm of him would be because the News was extremely right wing. The critism is based on the News’ policy of distorting facts not its right wing, rascist, anti-labor editorial policies.

4. Actually having grown up in Detroit IS relevant. I was reading the News since I was approximately 7 years old while growing up in the city that it was vreporting on. You might disagree with my opinion but certainly the fact that I was reading the News since I was about 7 years old while living, hanging out, working and going to school in the city that it was reporting on must seem relevant even to someone looking to use semi-cheap neo-logic to respond to anyone that expresses an oponion that you don’t like.

5. Actually, the truth matters. And I don’t know anyone who disagrees with my statement RE: the News. Do you?

6. Come on; you can do better than that. I was responding to Cain’s attempts to paint anyone who disagreed with him as having an idealogical time warp. He expressed a clear point of view and then personally demonized anyone who disagreed. You’r not really suggesting that anyone who states that someone else is engaging in personal attacks is him or herself engaging in personal attacks are you?

If you wanted to accuse me of being thinking that Cain’s comments are silly, you’d be more accuarte.

Finally, your point of view might have more weight if you were more even handed in which comments that you choose to jump on.

But, thats the nature of intrernet comments, isn’t it?

1. Angrily attacked? Cite please.

2. The only comment by Cain I see that ascribes anything to anyone’s personality at all is “I suspect that Chester and Rothberger remain the prisoners of what they see through their ideological lenses and that their comments reveal more about them than they do about Fleming.” He may be wrong in that, but I don’t see him attacking “anyone who disagrees” or calling anyone a liar.

3. …no, this is too boring to go on with. You are painting some pretty specific claims and disagreements as something much larger by going on and on about how he “paints anyone who disagrees” as this and that, and it’s just bogus. In fact, you took a relatively limited disagreement and, OK, an ill-advised but essentially pretty mild crack about your ideological lenses, refracted it through your own resentment and, expended many, many lines being a big, whiny, posturing baby.

I’ve never met Stephen Cain and was not of fan of his reporting for the Ann Arbor News (I don’t remember his byline in the Detroit News–I grew up in a Free Press family–but have always felt as you do about the editorial policies of the News, and the Ann Arbor News wasn’t much better). So I have no axe to grind here. But the reason I “jumped on” your comments and not his is that he wasn’t being a jackass and you are.

Oh. Spoken as the punk that you are. But you can have the last word.

As a sophomore at U-M living in South Quad, politically aware but not a member of any activist group at that time, I was quite interested in the movement to have a student run bookstore. I was incensed when the administration put leaflets in the student mailboxes in all the dorms, giving only their position and using what I felt was highly questionable and distorted information.

Without thinking really, I grabbed a friend and walked down South U to President Fleming’s house at about 4:30 in the afternoon. My only previous experience with his house was at rallies the previous year when hundreds of protesting students would rally on his lawn. I never knew anyone to knock on his door, expecting to talk with him.

But this is what I did. I was asked to wait, and after 5-10 minutes Fleming came down, offered us a seat and asked what was on our mind. I explained and demanded the right for students to also have the right to blanket the mailboxes with our side of the story, free of charge.

He listened, he disagreed with our statements, he denied our request, but he gave us time, and was civil throughout. Make of this what you will. It was only afterwards that I understood that this experience was out of the ordinary. Too often we feel powerless, unable or unwilling to speak up, and out of reach of leaders and decision makers. This showed at least not all of the above is true.

I was a researcher and then faculty member at UM. My research focused on student organizations, including Voice (which preceded SDS) and the conservative Young Americans for Freedom. I was a faculty member at the Center for the Study of Higher Education.

I wrote an article for the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education entitled “Michigan Muddles Through” about the 60′s at Michigan. I did not know Robben Fleming, though I met with him once about the article. I asked in the article why Michigan didn’t go violent like other campuses around the country– Berkeley and Columbia especially. I argued that the liberal faculty –in the social sciences and law–who were dominant at Michigan mediated between the students as well as young faculty and the administration. This happened in the first anti-Vietnam teach-in in 1965 (in which I was involved) and during the protests on South University Ave. when the faculty were on the street talking to the protestors. Law students led BAM. Their sense of strategy and understanding of negotiating tactics made BAM tough and realistic.

Of course, Fleming’s professional training in negotiation and his unflappable personality helped avert violence by students and the police. His greatest contribution was the way he handled the Regents by explaining the students’ concerns and by resisting their pressure to use force.

I notice that you published comments by UM grad Bill Ayers, one of the leaders of the Jesse James Gang, which morphed into the Weather Underground. I don’t recall whether that group ever engaged in action on the UM campus. They would not then have come to the attention of Robben Fleming.

I think that Jeff Gaynor’s comment actually proves the point that Fleming’s job was to coopt dissent without actually engaging the issues. According to the comment, Fleming responded to complaints that the U was inserting into students’ mailboxes a one sided view of the bookstore issue by politely hearing Gaynor out and then refusing to allow students the opportunity to present their point of view through the same method that the U used to spread its opinion, let alone being willing to consider changing the U’s position on the bookstore.

Most people would agree that Fleming was skillful. But it seems to me that that is not the point; the point is what interests he chose to apply his skills to. No one expected that Fleming would go against his employers’ demand that he oppose the bookstore. But he was not even willing to allow a free and equal discussion of the issue to occur. In the bookstore issue Jeff Gaynor went home inmpressed that Fleming heard him out even though Fleming and the U refused to change its policies of denying students access to spread their point of view in the same manner that the U used. (After all the U was using students’ mailboxes to spread its viewpoint; it would seem that students should have the same opportunity).

Nor is it accurate to say that Fleming averted police violence. As has been described above, the police rioted on and off campus in 1967. Fleming’s response was to dodge the issue until the amount of violence forced him to issue a “very weak” statement.

As to student violence or the lack of it, those of us who engaged in demostrations and civil disobedience at the U and in Ann Arbor made our own decisions whether to engage in non-violence. The vast, vast majority didn’t. That wasn’t because of Fleming, it was because of our own values. And when the police rioted many, many students and non-students alike responded.

And, of course, after a group of students took action and committed civil disobedience, the U and Fleming sudddenly decided that a bookstore wasn’t such a bad idea after all. What’s the lesson in that? Why did it take students getting arrested to ghet the U to enter into real discussion?

I’ve always found it so ironic that the “radicals” of today and yesterday are almost always rich white people that have chosen short-term destitution in an effort to gain street credibility and a sense of authenticity.

Problem is, you can return to your trust funds when your four years of intentional poverty are up. The poor people can’t. That’s why very few people, even the poor people you were trying to help, ever took you seriously.